Abstract

Pathological, non-carious loss of tooth tissue is an increasing problem to the dental profession, with young individuals especially at risk. This paper provides an overview of the problem with an emphasis on the possible causes, particularly those factors which may account for the increased incidence. The clinical appearance produced by the various aetiological factors is discussed and recommendations made on the objectives of the immediate and long-term management of the problem.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The management of tooth surface loss (TSL) demands a full understanding of its aetiology and presentation. This paper provides the introduction to the series and an overview of pathological, non-carious loss of tooth tissue. Emphasis is placed on the aetiological factors which are currently thought to be major causes of this problem. This directs the paper toward those agents that produce erosive tooth surface loss. This is appropriate given the increasing incidence and severity of this type of tooth wear.

The article attempts only relatively brief descriptions of the presentation and aetiology of attritional and abrasive tooth surface loss. This does not imply that they are less important but rather reflects the increased concern over the need for prevention, early detection and control of acid erosion. Later articles in the series will return to the presentation and management of the other types of TSL. The preventive management of bruxism is described in the third and sixth paper.

Non carious loss of tooth tissue is a normal physiological process and occurs throughout life.1 If the rate of loss is likely to prejudice the survival of the teeth, or is a source of concern to the patient, then it may be considered 'pathological'.2 The dental management of patients with such loss of tooth tissue has provided difficulties for the dental profession for many years and it is generally agreed that the problem is increasing. This can only partly be explained by the fact that the population is retaining more natural teeth into old age.2,3 It is not only the middle-aged and elderly who exhibit pathological loss of tooth tissue, but also younger age groups (fig. 1).4 Robb reported that the prevalence of pathological loss of tooth tissue in patients less than 26 years of age was greater than in many older age groups.5 The Child Dental Health Survey (1994)6 confirmed this when 32% of 14-year-olds had evidence of erosion affecting the palatal surfaces of their permanent incisors. This cannot be explained as an age-related phenomenon. It may, however, be the result of changing lifestyles and social pressures which have led to the increased prominence of particular aetiological factors.

Aetiology

Traditionally, the terms 'erosion', 'abrasion' and 'attrition' have been used to describe the non-carious, pathological loss of tooth tissue (Table 1). These terms reflect the specific aetiological factors which are associated with the loss of tooth tissue. Eccles suggested that the term 'tooth surface loss' should be used when a single aetiological factor was often difficult to identify.7 Smith and Knight, however, considered that 'TSL' belittled the severity of the problem and, therefore, advocated the use of the term 'tooth-wear' to embrace all three aetiological conditions.2 Broad terms to describe the processes involved are helpful since a single aetiology is less common.8,9 For clarity, 'TSL' will be used throughout this paper to describe the pathological, non-carious loss of tooth tissue although 'tooth-wear' and 'TSL' are often interchangeable. The terms, 'erosion', 'abrasion' and 'attrition' are still useful where there is a clear indication of a specific aetiology or where aetiological factors are being discussed.

Erosion

It would appear that erosion is a major cause of TSL. Smith and Knight, for example, could exclude it as a cause of TSL in only 11% of patients examined.10 Traditionally, factors which may cause erosion have been described as originating from the following sources:11

-

Dietary

-

Regurgitation

-

Environmental.

Dietary erosion

Dietary erosion may result from food or drinks containing a variety of acids, especially citric acid which may chelate as well as dissolve calcium ions.12 Citric and phosphoric acid are common constituents of soft drinks and fruit juices (Table 2).13 These beverages are now widely available, with a doubling of sales in the UK, since 1970 and a 7-fold increase since 1950 (Fig. 2).9 Adolescents and children account for 65% of sales with 42% of fruit drinks consumed by children between the ages of 2 and 9 years old.9,14 This consumption of soft drinks by this age group has been identified as the probable cause for the erosion recorded in the Child Dental Health Survey (1994).6

Slimness and 'healthy eating' are now perceived to be important in western society. This has helped the newer 'diet' drinks to achieve a greater share of the sales market (fig. 3). These low calorie drinks are also acidic (Table 2) with, except for the sugar, similar constituents to the traditional beverages. The potential for erosive damage by these 'diet' beverages may be less well appreciated. The acidic nature of soft drinks, therefore, makes them a significant aetiological factor in TSL, particularly in younger patients. Eccles confirmed the importance of these beverages when he reported that they were implicated as aetiological factors in 40% of patients with TSL.15

A 'healthy' diet may also contain substantial acidic foods16,17,18 and cause further loss of tooth tissue. Furthermore, the abrasive nature of many of the components of these diets may accelerate TSL. (Certain dietary components, such as curries, also have the potential to cause TSL indirectly, by causing gastric reflux.19)

Regurgitation erosion

Regurgitation results in gastric acid entering the mouth. The regurgitation may be involuntary or self-induced as in bulimia nervosa.5,20

Involuntary regurgitation: Involuntary regurgitation is a common complication of gastro-intestinal problems such as hiatus hernia (fig. 4). The effect of the regurgitated acid on the teeth is well documented.21,22 Furthermore, medication used to treat such problems may also be a cause of TSL.22

Gastritis and acid regurgitation are common complications of chronic alcoholism, although patients may not be aware of the problem.23,24 Often the patient is secretive about the habit and confirmation is usually difficult. There is also a group of patients, for example the young adult, who have frequent alcoholic 'binges'. Such binges are often associated with episodes of vomiting. These patients tend to be less secretive about their alcohol consumption. Soft drinks which are frequently used as 'mixers' with alcoholic drinks may also contribute to TSL.

One of the major roles of saliva is to dilute and buffer any acid which enters the mouth and lubricate the occluding surfaces during mastication. If salivary flow is reduced, the potential for erosive and attritional damage increases.25 As medical science advances and life expectancy increases, the use of drugs within the population is more widespread.26 Many of these drugs cause a dry mouth and, as such, the associated problems are likely to become more prevalent.27 The problem may be compounded if patients consume acidic drinks in an attempt to alleviate the symptoms and stimulate salivary flow.

Voluntary regurgitation: Voluntary regurgita-tion may be practised by patients with an eating disorder. Such disorders are a feature of a body-conscious society and often begin in early adolescence, frequently running a chronic course with substantial complications.28 The prevalence of eating disorders in the general population would appear to be increasing with figures reported for anorexia nervosa of between 0.1-0.2% and 1-2% for bulimia nervosa. However, eating disorder patients may actively avoid detection or be reluctant to disclose details of their problem and as such the true prevalence may be underestimated.28,29

The effect of acid regurgitation in eating disorder patients has been well documented.30,31,32,33,34 The most common sign is perimolysis — erosive lesions localised to the palatal aspects of the maxillary teeth (fig. 5). These lesions are thought to be the result of the tongue directing gastric contents forward during voluntary and prepared vomiting with the lateral spread of the tongue protecting the lower teeth.16,32

The pattern of TSL in eating disorder patients may also be affected by other aetiological factors such as:16

-

Erosive 'diet' beverages and 'healthy' foods as patients strive to control their weight

-

Xerostomia, caused by vomit-induced dehydration or drugs such as diuretics, appetite suppressants and anti-depressants

-

Long-term complications such as gastric ulcers and hiatus hernia.28

Environmental erosion

Environmental erosion occurs when patients are exposed to acids in their work-place or during leisure activities.35,36 Health and safety laws have probably reduced the risk of environmental erosion although it should not be ignored as a possible aetiological factor.

Environmental erosion predominantly affects the labial surfaces of the maxillary and mandibular incisors.

Attrition

Attritional TSL primarily affects the occlusal and incisal surfaces of teeth although slight loss may occur at the approximal contact areas (fig. 6). This type of TSL can be particularly significant in patients with a vegetarian or a modern 'healthy' diet.37 Attritional TSL may also be a consequence of parafunctional activity.38,39

Abrasion

Abrasion is caused by abnormal rubbing of tooth tissue or restoration by a non-dental object eg pipe-smoking, hair-grips etc.11 However, the most common cause is probably incorrect or over vigorous toothbrushing37;although Smith and Knight10 found that the occurrence of abrasion was infrequent compared with other types of TSL (fig. 7). Furthermore, the location of some 'abrasive' lesions cannot be explained by toothbrushing alone and other TSL factors such as erosion may contribute to the problem.9,37 Recently, interest has grown in the role of occlusal stresses in the development of cervical 'abrasive' lesions and the term abfraction has been used to describe these.

Prevalence

It is generally accepted that the prevalence of TSL increases with age.5,40,41,42 However, the exact prevalence is unclear, primarily because of differing assessment criteria.42 Hugoson et al.,39 for example, reported that 13–24% of surfaces showed evidence of occlusal wear. Other studies have observed that between 25% and 50% of subjects had evidence of TSL.9 Some loss of tooth tissue is normal during a patients' lifetime as a result of 'wear and tear'. The loss is likely to be a problem only when the degree exceeds what would be considered 'normal' for a particular age. Studies which consider only 'pathological' TSL may, therefore, be more relevant to clinical dentistry. The tooth wear index (TWI)2 attempted to achieve this by proposing maximum acceptable tooth tissue loss for each decade of life. Tooth surface loss in excess of these figures was considered 'pathological'. Using this index, between 4.5 and 5.7% of surfaces examined exhibited TSL.2,5

Although the actual prevalence of TSL is unclear, there is general agreement that the population, particularly the young, is experiencing increased exposure to elements which cause TSL.4,5 The exact reason for this is unclear but the following factors may be implicated:

Body image

In the 1980s, fashion designers and image makers have promoted the concept that 'slimness' equates with 'attractive' or 'successful'. This concept is supported by role models who may have significantly influenced young people's perception of the 'ideal' body shape. In an attempt to control body weight patients may consume acidic foods such as fruit and diet drinks rather than high calorie alternatives. This struggle to achieve the 'ideal' body shape may also partly account for the increased prevalence of eating disorders.

Soft drink manufacturers

The soft drink industry is a multi-million pound business. Coca-Cola, for example, is the biggest brand label in the world with an estimated brand value of nearly $9,000 million. Marketing of soft drinks, traditionally, has been directed to the young adult by associating the beverages with peer group acceptability. More recently, the drinks have been promoted as 'healthy' and linked to high profile sportsmen and women. Consumption of acidic beverages following exercise may be more dangerous because of dehydration and a subsequent reduction in the buffering capacity of the saliva.

Refrigeration

Refrigeration has aided widespread accessibility to fruits, fruit-juices and soft drinks. It has allowed many fruits and vegetables to be available continually rather than when 'in season'. Consequently, diets can contain highly acidic foods and drinks all year round whereas previously many elements were restricted to particular times of the year.

Healthcare workers

Healthcare workers, such as doctors and dieticians, advocate that fresh fruit should be a component of a 'balanced' diet. These foods are, therefore, promoted as a 'healthy' option to 'harmful' alternatives. Patients are unlikely to be warned of the damage associated with acidic foods. Dentists may indirectly support this concept by advising their patients to avoid sugar. Patients may perceive that foods and drinks that do not contain sugar must therefore, be less damaging to their teeth. Dentists often suggest that patients should brush their teeth after exposure to foods and drinks containing sugar or acid, but such practices may accelerate TSL.43

Restorative materials

Dentists often use 'aesthetic' restorations, irrespective of whether the restoration is visible. Many of these materials have the potential to accelerate TSL, particularly if used on occluding surfaces in parafunctional patients (fig. 8).44,45

Clinical appearance of TSL

Although a 'classical' clinical appearance has been described for erosion, attrition and abrasion it is unlikely that the appearances described are a result of a single factor.46 If dietary acid is applied to a tooth surface then the surface becomes frosty and white. However, the clinical 'erosive' lesion is smooth and polished.37 Therefore attrition and/or abrasion is probably also present additionally. Even so, certain clinical features can indicate a dominant aetiological factor.

Teeth affected by erosion become rounded and lose their surface characteristics (figs 4 and 5). Attrition, however, is associated with flattening of the cusp tips or incisal edges and localised facets on the occlusal or palatal surfaces (fig. 6). Following dentine exposure, the clinical appearance is determined by the relative contributions of the aetiological factors. If the TSL is primarily attritional then the dentine will wear at the same rate as the surrounding enamel. In this situation the shape of the facet will be determined by the movement of the opposing tooth. Traditionally it is suggested that when an erosive factor is present, 'cupping' or 'grooves' form in the dentine and the base of the defect is not in contact with the opposing tooth (fig. 4).11 However, this may be an over-simplification of the changes that take place.

Cervical lesions caused by an abrasive tend to be angular and 'V'-shaped while erosion results in shallow, rounded lesions (fig. 7).

The clinical appearance of restorations may also indicate a possible major aetiological factor. Amalgam and composite restorations, for example, tend to be unaffected by erosive factors and remain 'proud' of the surrounding tooth tissue. However, both restorations show evidence of faceting if attrition is the major aetiological factor.11

Clinical problems

Aesthetics

Often a patient is only aware of TSL when there has been a deterioration in the appearance of the teeth. The earliest changes are because of the loss of enamel. This may cause an increase in tooth translucency, both interproximally and at the incisal edges.46 Continued TSL may produce fractures of the enamel and shortening of the teeth.47 The loss of enamel may also increase the visibility of the underlying dentine, producing a more yellow tooth colour.4

Conservation of tooth structure

The loss of tooth tissue is often substantial and the need to conserve remaining tooth structure is vital. This is particularly important in the young, where tooth tissue is at a premium because of the lack of secondary dentine. For this reason, 'adhesive' restorations should be considered before 'conventional' methods since the latter require further loss of tooth tissue.

Sensitivity and pain

Exposure of dentinal tubules and their subsequent bacterial colonisation can lead to both pulpal inflammation and sensitivity.48 In younger patients with rapid erosion, this is further exacerbated by the lack of secondary dentine and large pulps. In extreme cases, pulpal exposure can occur, further complicating management (fig. 5).

Inter-occlusal space

Berry and Poole,49 suggested that occlusal TSL is compensated by alveolar growth which maintains the occlusal vertical dimension (OVD). However, if the rate of loss is greater than the compensatory mechanism then the OVD is reduced. The effect of TSL on the occlusal vertical dimension is neither predictable nor uniform.

Patient compliance and expectations

Self-awareness and peer or social pressures may lead patients to refuse to comply with advice concerning the management of TSL. These concerns may result in the rejection of a proposed restorative treatment plan: metal palatal restorations, for example, may be unacceptable because of 'grey-out'.4 It is important that the implications of non-compliance and treatment alternatives are fully discussed with the patient.

Management

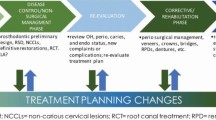

Immediate therapy

The aim of the immediate phase of therapy is to:

-

Relieve sensitivity and pain

-

Identify aetiological factors

-

Protect remaining tooth tissue.

All aetiological factors for the TSL should be identified and eliminated although full compliance may be difficult. At the very least a 'damage limitation' policy should be initiated. This should involve identification, control and advice relating to the causative factors. Consideration should be given to the following:

-

Diet analysis and counselling to control or reduce the effect of aetiological factors.50

-

Advice to consume erosive beverages through a wide-bore straw and to swallow immediately and not 'swish' the drink around the mouth. Although teeth should not be brushed immediately following exposure to erosive factors, the exact 'safe' time period when oral hygiene can be carried out is unknown. This may reduce the risk of abrasive TSL.9,43

-

Prescription of a neutral, sodium fluoride mouthrinse or gel for daily use to combat acid damage and control pulpal sensitivity.51 Acidulated phosphate fluoride should be avoided because of its obvious acidity.

-

Construction of a close fitting occlusal guard in those suspected of parafunctioning or where the aetiology is uncertain.52 A guard may also be useful in bulimics to protect the teeth during periods of vomiting. Alkali, such as milk of magnesia, can be applied to the fitting surface of the guard to neutralise any acid pooling or alternatively a neutral fluoride gel placed in the appliance.53 Appliances covering teeth must be used with extreme caution if there is a chance of acid being trapped beneath them.

-

Direct application of glass ionomer and/or composite to sensitive areas.

-

Consultation with the general medical practitioner regarding involuntary acidic reflux and/or psychiatrists to evaluate the patient's psychological status and background, especially in cases of bulimia nervosa.

Reassessment

Following immediate therapy, a period of time should elapse before a long-term treatment plan is considered allowing an evaluation of the patient's response to initial care. The reassessment should include whether the original aetiological factors are still present although this can be difficult to determine. Treatment needs can also be evaluated during this time and the patient's views and expectations considered.

Long-term management

The treatment planning options available are:

0Review and monitoring

Providing the patient has no functional, occlusal, aesthetic or sensitivity problems following stabilisation then close monitoring of the situation is acceptable. This should involve the construction of accurate study casts: a set of casts should be given to the patient so that if there is a change in dentist, the records are available. Colour transparencies or photographs are also useful. A regular recall regime should be initiated and the patient instructed to return if they suspect any deterioration. If the rate of TSL is likely to jeopardise the tooth's long-term viability, then monitoring of the situation alone is unwise and restoration becomes necessary.

Restorative treatment

Restorative treatment is indicated when stabilisation techniques have failed to resolve the patient's dental problems. It is a widely-held view that restorative treatment in the presence of ongoing TSL is unwise. Nevertheless, there are occasions when control proves impossible and, to preserve the teeth, restoration becomes essential. The patients should be aware of both the advantages and disadvantages of any proposed treatment. Restoration should be based on the following principles:

-

Protection and conservation of remaining tooth structure

-

Resolution of pulpal sensitivity

-

Improvement in aesthetics if necessary.

Conclusion

The paper has placed considerable emphasis on the aetiology of tooth surface loss as without an understanding of this, prevention and control are impossible. One of the major concerns in the United Kingdom is the increased incidence of TSL caused by acid erosion. Many of the reasons for this are dietary but others relate to regurgitation of acid. The next article in this series will discuss eating disorders in detail and the management of patients who are affected by this seemingly increasingly common condition.

References

Flint S, Scully C . Orofacial age changes and related disease. Dent Update 1988; 15: 337–342.

Smith B G N, Knight J K . An index for measuring the wear of teeth. Br Dent J 1984; 156: 435–438.

Watson I B, Tulloch E N . Clinical assessment of cases of tooth surface loss. Br Dent J 1985; 159: 144–148.

Bishop K A, Briggs P F A, Kelleher M G D . The aetiology and management of localized anterior tooth wear in the young adult. Dent Update 1994; 21: 153–161.

Robb, N . Epidemiological study of tooth wear. London: University of London, 1991.

O'Brien M . Childrens dental health in the United Kingdom. London: HMSO, 1994.

Eccles J D . Tooth surface loss from abrasion, attrition and erosion. Dent Update 1982; 35: 373–381.

Smith B G N . Some facets of toothwear. Ann R Aust Coll Dent Surg 1991; 11: 37–51.

Shaw L, Smith A . Erosion in children: An increasing clinical problem? Dent Update 1994; 21: 103–106.

Smith B G N, Knight J K . A comparison of patterns of tooth wear with aetiological factors. Br Dent J 1984; 157: 16–19.

Mair L H . Wear in dentistry — current terminology. J Dent 1992; 20: 140–144.

Jarvinen V K, Rytomaa I I, Heinonen, O P . Risk factors in dental erosion. J Dent Res 1991; 70: 942–947.

Kelleher M, Bishop K . Personal communication, 1994.

Rugg-Gunn A J, Hackett A F, Appleton D R, Jenkins G N, Eastoe J E . Relationship between dietary habits and caries increment assessed over two years in 405 English adolescent school children. Arch Oral Biol 1984; 29: 983–987.

Eccles J D . Erosion affecting the palatal surfaces of upper anterior teeth in young people. Br Dent J 1982; 152: 375–378.

Hellstrom I . Oral complications in anorexia nervosa. Scand J Dent Res 1977; 85: 71–86.

Giunta J L . Dental erosion resulting from chewable vitamin C tablets. J Am Dent Assoc 1983; 107: 253–256.

Linkosalo E, Markkanen H . Dental erosions in relation to lactovegetarian diet. Scand J Dent Res 1985; 93: 436–441.

Bartlett D W, Evans D F, Smith, B G N . Simultaneous oral and oesophageal pH measurement after a reflux provoking meal. J Dent Res 1994; Spec Issue Abst 70.

Jarvinen V, Meurman J H, Hyvarinen H et al. Dental erosion and upper gastrointestinal disorders. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1988; 65: 298–303.

Howden G F . Erosion as the presenting symptom in hiatus hernia. Br Dent J 1971; 131: 455–456.

Rytomaa I, Jarvinen V, Heinonen, O P . Etiological factors in dental erosion. J Dent Res 1990; 69: Spec. Issue.: Abst 587.

Simmons M S, Thompson D C . Dental erosion secondary to ethanol-induced emesis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Path 1987; 64: 731–713.

Smith B G N, Robb N D . Dental erosion in patients with chronic alcoholism. J Dent 1987; 17: 219–221.

Bloem T J, McDowell G C, Lang B R et al. In vitro wear. Part II wear and abrasion of composite restorative materials. J Prosthet Dent 1988; 60: 242–249.

Seymour R A . Dental pharmacology problems in the elderly. Dent Update 1988; 15: 375–380.

Levine R. S . Saliva: 3. Xerostomia - aetiology and management. Dent Update 1989; 16: 197–201.

Treasure J . Long-term management of eating disorders. Int Rev Psych 1991; 3: 43–58.

Kidd E A M, Smith B G N . Toothwear histories: a sensitive issue. Dent Update 1989; 20: 174–178.

Allen D N . Dental Erosion from Vomiting. Br Dent J 1969; 126: 311–312.

Andrew F F H . Dental erosion due to anorexia nervosa with bulimia. Br Dent J 1982; 152: 89–90.

Stege P, Visco-Dangler L, Rye L . Anorexia nervosa: review including oral & dental manifestations. J Am Dent Assoc 1982; 104: 648–652.

Abrams R A, Ruff L C . Oral signs and symptoms in the diagnosis of bulimia. J Am Dent Assoc 1986; 113: 761–764.

Gilmour A G, Beckett H A . The voluntary reflux phenomenon. Br Dent J 1993; 175: 368–371.

Petersen P E, Gormsen C . Oral conditions among German battery factory workers. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1991; 19: 104–106.

Centerwall B S, Armstrong C W, Funkerhouser L S, Elzay R . Erosion of dental enamel among competitive swimmers at a gas-chlorinated swimming pool. Am J Epidemiol 1986; 123: 641–647.

Smith B G N . Toothwear: aetiology and diagnosis. Dent Update 1989; 16: 204–212.

Krogh-Poulson W, Carlsen O R . Bidfunktion/Bettfysiologi. Denmark: Munksgaard, Kobenhavn. 1979; p269.

Dahl B L, Krogstad O, Karlsen K . An alternative treatment in cases with advanced localized attrition. J Oral Rehabil 1975; 2: 209–214.

Hugoson A, Bergendal T, Ekfeldt A, Helkimo M . Prevalence and severity of incisal and occlusal tooth wear in an adult Swedish population. Acta Odontol Scand 1988; 46: 255–265.

Ekfeldt A, Hugoson A, Bergendal T, Helkimo M . An individual tooth wear index and an analysis of factors correlated to incisal and occlusal wear in an adult Swedish population. Acta Odontol Scand 1990; 48: 343–349.

Donachie M A . The dental health of the ageing population of Newcastle upon Tyne. Newcastle: University of Newcastle, 1992.MDS thesis.

Davis W B, Winter P J . The effect of abrasion on enamel and dentine after exposure to dietary acid. Br Dent J 1980; 148: 253–256.

Jacobi R, Shillingburg H H T, Duncanson M G . A comparison of the abrasiveness of six ceramic surfaces and gold. J Prosthet Dent 1991; 66: 303–309.

Ratledge D K, Smith B G N, Wilson, R F . The effect of restorative materials on the wear of human enamel. J Prosthet Dent 1994; 72: 194–203.

Eccles J D, Jenkins W G . Dental erosion and diet. J Dent 1974; 2: 153–159.

Eccles J D . Dental erosion of non industrial origin. A clinical survey and classification. J Pros Dent 1979; 42: 649–653.

Brannstrom M . The cause of postrestorative sensitivity and its prevention. J Endodont 1986; 10: 475–481.

Berry D C, Poole D F G . Attrition: possible mechanisms of compensation. J Oral Rehabil 1976; 3: 201–206.

Kidd A M, Joyston-Bechal S . Essentials of dental caries: the disease and its management. Chapts 6 and 7. Bristol: Wright, 1987.

Bartlett D W, Smith B G N, Wilson, R F . Comparison of the effect of fluoride and non-fluoride toothpaste on tooth wear in vitro and the influence of enamel fluoride concentration and hardness of enamel. Br Dent J 1994; 176: 346–348.

Gierdrys-Leeper E . Night guards and occlusal splints. Dent Update 1990; 17: 325–329.

Kleier D J, Aragon S B, Averbach, R E . Dental management of the chronic vomiting patient. J Am Dent Assoc 1984; 108: 618–621.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on a presentation at The Medical Society of London on 5 October 1994 as part of the Alpha Omega lecture programme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kelleher, M., Bishop, K. Tooth surface loss: an overview. Br Dent J 186, 61–66 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800020a2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800020a2

This article is cited by

-

A student guide to tooth surface loss

BDJ Student (2022)

-

Tooth wear management and diagnosis

BDJ Student (2020)

-

Influence of Er,Cr:YSGG laser, associated or not to desensitizing agents, in the prevention of acid erosion in bovine root dentin

Lasers in Medical Science (2019)

-

The influence of management of tooth wear on oral health-related quality of life

Clinical Oral Investigations (2018)

-

Tooth wear in aging people: an investigation of the prevalence and the influential factors of incisal/occlusal tooth wear in northwest China

BMC Oral Health (2014)