Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has shown a markedly low proportion of cases among children1,2,3,4. Age disparities in observed cases could be explained by children having lower susceptibility to infection, lower propensity to show clinical symptoms or both. We evaluate these possibilities by fitting an age-structured mathematical model to epidemic data from China, Italy, Japan, Singapore, Canada and South Korea. We estimate that susceptibility to infection in individuals under 20 years of age is approximately half that of adults aged over 20 years, and that clinical symptoms manifest in 21% (95% credible interval: 12–31%) of infections in 10- to 19-year-olds, rising to 69% (57–82%) of infections in people aged over 70 years. Accordingly, we find that interventions aimed at children might have a relatively small impact on reducing SARS-CoV-2 transmission, particularly if the transmissibility of subclinical infections is low. Our age-specific clinical fraction and susceptibility estimates have implications for the expected global burden of COVID-19, as a result of demographic differences across settings. In countries with younger population structures—such as many low-income countries—the expected per capita incidence of clinical cases would be lower than in countries with older population structures, although it is likely that comorbidities in low-income countries will also influence disease severity. Without effective control measures, regions with relatively older populations could see disproportionally more cases of COVID-19, particularly in the later stages of an unmitigated epidemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

COVID-19 shows an increased number of cases and a greater risk of severe disease with increasing age5,6, a feature shared with the 2003 SARS epidemics7. This age gradient in reported cases, which has been observed from the earliest stages of the pandemic1, could result from children having decreased susceptibility to infection, a lower probability of showing disease on infection or a combination of both, compared with adults. Understanding the role of age in transmission and disease severity is critical for determining the likely impact of social-distancing interventions on SARS-CoV-2 transmission8, especially those aimed at schools, and for estimating the expected global disease burden.

Here, we disentangle the relative contributions of three potential drivers of the observed distribution of clinical cases by age. We present a summary of the main findings, limitations and implications of this work in Table 1.

First, age-varying susceptibility to infection by SARS-CoV-2, where children are less susceptible than adults to becoming infected on contact with an infectious person, would reduce cases among children. Decreased susceptibility could result from immune cross-protection from other coronaviruses9,10,11, or from non-specific protection resulting from recent infection by other respiratory viruses12, which children experience more frequently than adults13,14. Direct evidence for decreased susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 in children has been mixed15,16, but if true could result in lower transmission in the population overall.

Second, children could experience mild or no symptoms on infection more frequently than adults. Clinical cases result from infections that cause noticeable symptoms, such that the person may seek clinical care. An infection that does not result in a clinical case may be truly asymptomatic, or may be paucisymptomatic—that is, resulting in mild symptoms that may not be noticed or reported even though they occur. We refer to both asymptomatic and paucisymptomatic infections as ‘subclinical infections’—which are more likely to remain undetected than clinical cases—and refer to the age-specific proportion of infections resulting in clinical symptoms as the ‘clinical fraction’. Age-dependent variation in severity has been observed for other respiratory virus infections17, including SARS17,18. For COVID-19, there are strong indications of age dependence in severity5,19 and mortality18,19 among those cases that are reported, which could extend more generally to age-dependent severity and likelihood of clinically reportable symptoms upon infection. If infected children are less likely to show clinical symptoms, then the number of cases reported among children would be lower, but children with subclinical symptoms could still be capable of transmitting the virus to others, potentially at lower rates than fully symptomatic individuals, as has been shown for influenza20.

Third, differences in contact patterns among individuals of different ages, and setting-specific differences in age distribution, themselves affect the expected number of cases in each age group. Children tend to make more social contacts than adults21 and hence, all else being equal, should contribute more to transmission than adults22,23. If the number of infections or cases depends strongly on the role of children, countries with different age distributions could exhibit substantially different epidemic profiles and overall impact of COVID-19 epidemics.

The higher contact rates in children are why school closures are considered a key intervention for epidemics of respiratory infections22, but the impact of school closure depends on the role of children in transmission. The particular context of SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China, could have resulted in a skewed age distribution because early cases were concentrated in adults over 40 years of age24, and assortative mixing between adults could have reduced transmission to children in the very early stages of the outbreak. Outside China, COVID-19 outbreaks may have been initially seeded by working-age travelers entering the country25,26, producing a similar excess of adults in early phases of local epidemics. In both cases, the school closures that occurred subsequently potentially further decreased transmission among children, but to what degree is unclear.

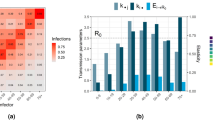

We developed an age-stratified transmission model with heterogeneous contact rates between age groups (Fig. 1a), and fitted three variants of this model to the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan: one in which susceptibility to infection varies by age, one in which clinical fraction varies by age and one with no age-dependent variation in either susceptibility or clinical fraction (Fig. 1b,c and see Methods). We fitted to two data sources from the Wuhan epidemic: a time series of reported cases1 and four snapshots of the age distribution of cases1,27 (Fig. 1 and Extended Data Fig. 1). We assumed that initial cases were in adults, and accounted for school closures in the model by decreasing the school contacts of children starting on 12 January 2020, when schools were closed for the Lunar New Year holiday. We also estimated the effect of the Lunar New Year holiday period on non-school contact rates from 12 January to 22 January 2020, as well as the impact on transmission of travel and movement restrictions in Wuhan, which came into effect on 23 January 2020 (Fig. 1d). We found that, under each hypothesis, the basic reproduction number R0 was initially 2.5–2.8, was inflated 1.2–1.4 fold during the pre-Lunar New Year holiday period and then fell by 60–70% during restrictions in Wuhan (Fig. 1e).

a, Model diagram and duration of disease states in days, where d parameters represent the duration of time in each disease state (see Methods), yi is the fraction of infections that manifest as clinical cases in age group i, λi is the force of infection in age group i, PI is the incubation period and PS is the serial interval (see Methods). b, Susceptibility by age for the three models, with mean (lines), 50% (darker shading) and 95% (lighter shading) credible intervals shown. Age-specific values were estimated for model 1 (orange). Susceptibility is defined as the probability of infection on contact with an infectious person. c, Clinical fraction (yi) by age for the three models. Age-specific values were estimated for model 2 (blue) and fixed at 0.5 for models 1 and 3. d, Fitted contact multipliers for holiday (qH) and restricted periods (qL) for each model showed an increase in non-school contacts beginning on 12 January (start of the Lunar New Year) and a decrease in contacts following restrictions on 23 January. e, Estimated R0 values for each model. The red barplot shows the inferred window of spillover of infection. f, Incident reported cases (black) and modeled incidence of reported clinical cases for the three models fitted to cases reported by China Centers for Disease Control (CCDC)1 with onset on or before 1 February 2020. Lines mark the mean and the shaded window is the 95% highest density interval (HDI). g, Age distribution of cases by onset date as fitted to the age distributions reported by Li et al.27 (first three panels) and CCDC1 (fourth panel). Data are shown in open bars and model predictions in filled bars, where the dot marks the mean posterior estimate. h, Implied distribution of subclinical cases by age for each model. Credible intervals on modeled values show the 95% HDIs; credible intervals on data for g and h show 95% HDIs for the proportion of cases in each age group.

All model variants fitted the daily incident number of confirmed cases equally well (Fig. 1f), but the model without age-varying susceptibility or clinical fraction could not reproduce the observed age distribution of cases. In this model, the number of cases in children was overestimated and cases in older adults were underestimated (Fig. 1g), suggesting that initial seeding among older individuals, together with the impact of school closures, did not explain the lack of observed cases among children. The other two model variants showed an improved fit to the observed age distribution of cases; both models suggested that 20% of all infections occurred in those aged over 70 years. However, the model that assumed no age variation in the clinical fraction implied that a large proportion (50%) of infections among the elderly would be mild or asymptomatic, compared with less than 25% when clinical fraction varied with age (Fig. 1h). Age-dependent severity has been demonstrated in hospitalized confirmed cases16,28, which suggests that subclinical infection in individuals aged over 70 years is probably rare and supports that the clinical fraction increases with age. Comparison using the deviance information criterion6 (DIC) showed that the age-varying susceptibility (DIC, 697) and age-varying clinical fraction (DIC, 663) model variants were preferred over the model with neither (DIC, 976).

Both age-varying susceptibility and age-varying clinical fraction could contribute in part to the observed age patterns. There is evidence for both age-varying susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection15 and age-varying severity9,18,19 in COVID-19 cases. A fourth model variant in which both susceptibility and clinical fraction vary by age was able to reproduce the epidemic in Wuhan, and was statistically preferred to any other model variant (DIC, 658; Extended Data Fig. 2). However, because decreased susceptibility and decreased clinical fraction have a similar effect on the age distribution of cases, it is necessary to use additional sources of data to disentangle the relative contribution of each to the observed patterns.

We used age-specific case data from 32 settings in six countries (China1,29, Japan30,31, Italy32, Singapore25, Canada33 and South Korea26) and data from six studies giving estimates of infection rates and symptom severity across ages16,19,34,35,36,37, to simultaneously estimate susceptibility and clinical fraction by age (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 3). We fitted the stationary distribution of the next-generation matrix to these data sources, using setting-specific demographics, with measured contact matrices where possible and synthetic contact matrices otherwise (see Methods)38. The age-dependent clinical fraction was markedly lower in younger age groups in all regions (Fig. 2b), with 21% (12–31%) of infections in those aged 10 to 19 years resulting in clinical cases, which increased to 69% (57–82%) in adults aged over 70 years in the consensus age distribution estimated across all regions. The age-specific susceptibility profile suggested that those aged under 20 years were half as susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection as those aged over 20 years (Extended Data Fig. 4). Specifically, relative susceptibility to infection was 0.40 (0.25–0.57) in those aged 0 to 9 years, compared with 0.88 (0.70–0.99) in those aged 60 to 69 years.

a, Age-specific reported cases from 13 provinces of China, 12 regions of Italy, Japan, Singapore, South Korea and Ontario, Canada. Open bars are data and the colored lines are model fits with 95% HDI. b, Fitted mean (lines) and 95% HDI (shaded areas) for the age distribution in the clinical fraction (solid lines) and the age distribution of susceptibility (dashed lines) for all countries. The overall consensus fit is shown in gray. c, Fitted incidence of confirmed cases and resulting age distribution of cases using either the consensus (gray) or country-specific (color) age-specific clinical fraction from b.

To determine whether this consensus age-specific profile of susceptibility and clinical fraction for COVID-19 was capable of reproducing epidemic dynamics, we fitted our dynamic model to the incidence of clinical cases in Beijing, Shanghai, South Korea and Italy (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 5). The consensus age-specific susceptibility and clinical fraction were largely capable of reproducing the age distribution of cases, although there are some outliers, for example in the 20- to 29-year-old age group in South Korea. This could, however, be the result of clustered transmission within a church group in this country4. The predicted age distribution of cases for Italy is also less skewed toward adults, especially those over 70 years, than reported cases show, suggesting potential differences in age-specific testing in Italy39. Locally estimated age-varying susceptibility and clinical fraction captured these patterns more precisely (Fig. 2c).

School closures during epidemics40,41 and pandemics42,43 aim to decrease transmission among children22 and might also have whole-population effects if children are major contributors to community transmission rates. The effect of school closures will depend on the fraction of the population that are children, the contacts they have with other age groups, their susceptibility to infection and their infectiousness if infected. Using schematic values for pandemic influenza44 and our inferred values for COVID-19 (Fig. 3a), we simulated epidemics in three cities with very different demographics: Milan, Italy (median age of 43 years), Birmingham, UK (median age of 30 years) and Bulawayo, Zimbabwe (median age of 15 years) (Fig. 3b), using measured contact matrices for each country. There were many more clinical cases for COVID-19 than influenza in all cities (mean clinical case rate across the three cities: 287 per 1,000 for COVID-19 versus 23 per 1,000 for influenza), with more cases occurring in under-20s (67%) in the influenza-like scenario compared with COVID-19 (17%) (Fig. 3c). More clinical cases were in adults aged over 20 years in Milan compared with the other cities, with a markedly younger age distribution of cases in the simulated epidemic in Bulawayo.

a, Age dependence in clinical fraction (severity) and susceptibility to infection on contact for COVID-19 and for the influenza-like scenarios (simplified, based on ref. 44) considered here. b, Age structure for the three exemplar cities. c, Age-specific clinical case rate for COVID-19 and influenza-like infections, assuming 50% infectiousness of subclinical infections. d, Daily incidence of clinical cases in exemplar cities for COVID-19 versus influenza-like infections. R0 is fixed at 2.4. The rows show the effect of varying the infectiousness of subclinical infections to be 0%, 50% or 100% as infectious as clinical cases while keeping R0 fixed. e, Change in peak timing and peak cases for the three cities, for either COVID-19 or influenza-like infections. f, Change in median COVID-19 peak timing and peak cases for the three cities, depending on the infectiousness of subclinical infections.

To explore the effect of school closure, we simulated three months of school closures with varying infectiousness of subclinical infections, at either 0%, 50% or 100% the infectiousness of clinical cases (Fig. 3d). For influenza-like infections we found that school closures decreased the peak incidence by 17–35% across settings, and delayed the peak by 10–89 days across settings (Fig. 3e). For COVID-19 epidemics, the delay and decrease of the peak was smaller (10–19% decrease in peak incidence, 1–6-day delay in peak timing), reflecting findings that school closures in response to SARS-CoV-1 did not have a substantial effect on SARS cases45. Among the three cities analyzed here, school closures had the least impact in Bulawayo, which has both the youngest population and the fewest contacts in school relative to the other cities (19% of contacts for 0- to 14-year-olds occurring in school, compared with 39% in Birmingham and 48% in Milan). This pattern could be generalizable to other low-income settings. Because children have lower susceptibility and exhibit more mildly symptomatic cases for COVID-19, school closures were slightly more effective at reducing transmission of COVID-19 when the infectiousness of subclinical infections was assumed to be high. School closures reduced median peak cases by 8–17% for 0% infectiousness, by 10–20% for 50% infectiousness and by 11–21% for 100% infectiousness of subclinical infections across each of the settings (Fig. 3f).

Age dependence in susceptibility and clinical fraction has implications for the projected global burden of COVID-19. We simulated COVID-19 epidemics in 146 capital cities and found that the total expected number of clinical cases in an unmitigated epidemic varied between cities depending on the median age of the population, which is a proxy for the age structure of the population (Fig. 4). There were more clinical cases per capita projected in cities with older populations (Fig. 4a), and more subclinical infections projected in cities with younger populations (Fig. 4b). However, the mean estimated basic reproduction number, R0, did not substantially differ by median age (Fig. 4c), because, across cities, the lower susceptibility and clinical fraction in children relative to adults was counteracted by greater contact rates among children relative to adults. Our finding that cities with younger populations are expected to show fewer cases than cities with older populations depends on all cities having the same age-dependent clinical fraction. However, the relationship between age and clinical symptoms could differ across settings because of a different distribution of comorbidities46 or setting-specific comorbidities (such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)47), for example. If children in low-income and lower–middle-income countries tend to show a higher clinical fraction than children in higher-income countries, then there could be higher numbers of clinical cases in these cities (Extended Data Fig. 6).

a, Expected clinical case attack rate (mean and 95% HDI) and peak in clinical case incidence for 146 countries in the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) country groupings50 for an unmitigated epidemic. b, Expected subclinical case attack rate and peak in subclinical cases. c, Estimated basic reproduction number (R0) in the capital city of each country assuming the age-specific clinical fraction shown in Fig. 2b and 50% infectiousness of subclinically infected people. d, Proportion of clinical cases in each age group at times relative to the peak of the epidemic. The 146 city epidemics were aligned at the peak, and colors mark the GBD groupings in a. e, Age distribution of the first and last thirds of clinical cases for 146 countries in GBD country groupings.

The expected age distribution of cases shifted substantially during the simulated epidemics. In the early phase there were more cases in the central age group (20–59 years) and after the peak a higher proportion of cases in those younger than 20 years and those older than 60 years (Fig. 4d). The magnitude of the shift was higher in those countries with a higher median age, which affects projections for likely healthcare burdens at different phases of the epidemic (Fig. 4e), particularly because older individuals, such as those over 60 years, tend to have high healthcare utilization if infected1.

We have shown age dependence in susceptibility to infection and in the probability of having clinically symptomatic presentation of COVID-19, from ~20% in children to ~70% in older adults. For a number of other pathogens, there is evidence that children (except for the very youngest, 0–4 years of age) have lower rates of symptomatic disease12 and mortality26, so the variable age-specific clinical fraction for COVID-19 we find here is consistent with other studies48. We have quantified the age-specific susceptibility from available data, and other study types will be needed to build the evidence base for the role of children, including serological surveys and close follow-up of those in infected households.

The age-specific distribution of clinical infection we have found is similar in shape (but larger in scale) to that generally assumed for pandemic influenza, but the age-specific susceptibility is inverted. These differences have a large effect on how effective school closures could be in limiting transmission, delaying the peak of expected cases and decreasing the total and peak numbers of cases. For COVID-19, school closures are likely to be much less effective than for influenza-like infections.

It is critical to determine how infectious subclinical infections are compared with clinically apparent infections so as to properly assess predicted burdens both with and without interventions. It is biologically plausible that milder cases are less transmissible, for example, because of an absence of cough16,28, but direct evidence is limited49 and viral load is high in both clinical and subclinical cases36. If those with no or mild symptoms are efficient transmitters of infection compared with those with fully symptomatic infections, the overall burden is higher than if they are not as infectious. At the same time, lower relative infectiousness would reduce the impact of interventions targeting children, such as school closure. By analyzing epidemic dynamics before and after school closures, or close follow-up in household studies, it might be possible to estimate the infectiousness of subclinical infections, but this analysis will rely on granular data by age and time.

A great deal of concern has been directed toward the expected burden of COVID-19 in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), which generally have a lower population median age than many high-income countries. Our results show that these demographic differences, coupled with a lower susceptibility and clinical fraction in younger ages, can result in proportionally fewer clinical cases than would be expected in high-income countries with flatter demographic pyramids. This finding should not be interpreted as fewer cases in LMICs, because the projected epidemics remain large. Moreover, the relationships found between age, susceptibility and clinical fraction are drawn from high-income and middle-income countries and might reflect not only age, but also the increasing frequency of comorbidities with age. This relationship could therefore differ in LMICs for two key reasons. First, the distribution of non-communicable comorbid conditions—which are already known to increase the risk of severe disease from COVID-1918—might be differently distributed by age50, along with other risk factors such as undernutrition51. Second, communicable comorbidities such as HIV47, tuberculosis co-infection (which has been suggested to increase risk52) and others53 could alter the distribution of severe outcomes by age. Observed severity and burden in LMICs might also be higher than in HICs due to a lack of health system capacity for intensive treatment of severe cases.

There are some limitations to the study. Information drawn from the early stages of the epidemic is subject to uncertainty; however, age-specific information in our study is drawn from several regions and countries, and clinical studies1,54 support the hypothesis presented here. We assumed that clinical cases are reported at a fixed fraction throughout the time period, although there may have been changes in reporting and testing practices that affected case ascertainment by age. We assumed that subclinical infections are less infectious than clinically apparent infections. We tested the effects of differences in infectivity on our findings (Extended Data Figs. 7 and 8) but were not able to estimate how infectious subclinical cases were. The sensitivity analyses showed very similar clinical fraction and susceptibility with age, and we demonstrated the effect of this parameter on school closure and global projections (Fig. 3 and Extended Data Fig. 8). We used mixing matrices from the same country, but not the same location as the fitted data. We used contact matrices that combined physical and conversational contacts. We therefore implicitly assume that they are a good reflection of contact relevant for the transmission of SARS-CoV-2. However, if fomite or fecal–oral routes are important contributors to transmission, these contact matrices might not be representative of overall transmission risk.

The role of age in transmission is critical to designing interventions aiming to decrease transmission in the population as a whole and to projecting the expected global burden. Our findings, together with early evidence16, suggest that there is age dependence in susceptibility and in the risk of clinical symptoms following infection with SARS-CoV-2. Understanding if and by how much subclinical infections contribute to transmission has implications for predicted global burden and the effectiveness of control interventions. This question must be resolved to effectively forecast and control COVID-19 epidemics.

Methods

Transmission model structure used in all analyses

We used an age-structured deterministic compartmental model (Fig. 1a) stratified into 5-year age bands, with time approximated in discrete steps of 0.25 days. Compartments in the model are stratified by infection state (S, E, IP, IC, IS or R), age band and the number of time steps remaining before transition to the next infection state. We assume that people are initially susceptible (S) and become exposed (E) after effective contact with an infectious person. After a latent period, exposed individuals either develop a clinical or subclinical infection; an exposed age-i individual develops a clinical infection with probability yi, otherwise developing a subclinical infection. Clinical cases are preceded by a preclinical (that is, pre-symptomatic) but infectious (IP) state; from the preclinical state, individuals develop full symptoms and become clinically infected (IC). Based on evidence for other respiratory infections20, we assume that subclinical infections (IS) are less infectious compared with preclinical and clinical infections, and that subclinical individuals remain in the community until they recover. We use 50% as a baseline for the relative infectiousness of individuals in the subclinical state and test the effects of varying other values (Extended Data Figs. 7 and 8). Isolated and recovered individuals eventually enter the removed state (R); we assume these individuals are no longer infectious and are immune to re-infection.

The length of time individuals spend in states E, IP, IC or IS is distributed according to distributions dE, dP, dC or dS, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). The force of infection for an individual in age group i at time t is

where ui is the susceptibility to infection of an age-i individual, cij,t is the number of age-j individuals contacted by an age-i individual per day at time t, f is the relative infectiousness of a subclinical case and \(\left( {I_{{\rm{P}}j} + I_{{\rm{C}}j} + fI_{{\rm{S}}j}} \right)/N_j\) is the effective probability that a random age-j individual is infectious. Contacts vary over time t depending on the modeled impact of school closures and movement restrictions (see below).

To calculate the basic reproductive number, R0, we define the next-generation matrix as

R0 is the absolute value of the dominant eigenvalue of the next-generation matrix.

We use the local age distribution for each city or region being modeled and synthetic or measured contact matrices for mixing between age groups (Supplementary Table 1). The mixing matrices have four types of contact: home, school, work and other contacts.

Comparing models by fitting to the epidemic in Wuhan

We contrasted three model variants. In model variant 1, susceptibility varied by age (ui = u(i)), but the proportion of exposed individuals who became clinical cases did not vary (yi = y). In model variant 2, the clinical case probability varied by age (yi = y(i)), but susceptibility did not (ui = u). In model variant 3, there were no age-related differences in susceptibility or clinical fraction (ui = u, and yi = y). Susceptibility and clinical fraction curves were fitted using three control points for young, middle and old age, interpolating between them with a half-cosine curve (see the following for details).

We assumed that the initial outbreak in Wuhan was seeded by introducing one exposed individual per day of a randomly drawn age between Amin and Amax for 14 days starting on a day (tseed) in November29,30. We used the age distribution of Wuhan City prefecture in 201655 and contact matrices measured in Shanghai31 as a proxy for large cities in China. This contact matrix is stratified into school, home, work and other contacts. We aggregated the last three categories into non-school contacts and estimated how components of the contact matrix changed early in the epidemic in response to major changes. Schools closed on 12 January for the Lunar New Year holiday, so we decreased school contacts, but the holiday period may have changed non-school contacts, so we estimate this effect by inferring the change in non-school contact types, qH. Large-scale restrictions started on 23 January 2020 following restrictions on travel and movement imposed by the authorities, and we inferred the change in contact patterns during this period, qL. Specifically:

where

and

We fitted the model to incident confirmed cases from the early phase of the epidemic in China (8 December 2019 to 1 February 2020) reported by China CDC1. During this period, the majority of cases were from Wuhan City, and we truncated the data after 1 February because there were more cases in other cities after this time. We jointly fitted the model to the age distribution of cases at three time windows (8 December 2019 to 22 January 2020) reported by Li et al.27 and a further time window (8 December 2019 to 11 February 2020) reported by China CDC1. Because there was a large spike of incident cases reported on 1 February that were determined to have originated from the previous week, we amalgamated all cases from 25 January to 1 February, including those in the large spike, into a single data point for the week. We assumed 10% of clinical cases were reported19. We used a Dirichlet distribution with a flat prior to obtain 95% HDIs for reported case data stratified by age group for display in figures.

We used a Markov chain Monte Carlo method to jointly fit each hypothesis to the two sets of empirical observations from the epidemic in Wuhan City, China (Supplementary Table 2). We used a negative binomial likelihood for incident cases and a Dirichlet-multinomial likelihood for the age distribution of cases, using the likelihood

where Ck is the observed incidence on day k and ck is the model-predicted incidence for day k, for each of K days. Am is the observed age distribution for time period m (case counts for each age group), am is the model-predicted age distribution for the same period and \(\left\| {a_m} \right\|\) is the total number of cases over all age groups in time period m, measured for M time periods. We set the precision of each distribution to 200 to capture additional uncertainty in data points that would not be captured with a Poisson or multinomial likelihood model.

For all Bayesian inference (shown in Figs. 1 and 2) we used a differential evolution Markov chain Monte Carlo method56, first running numerical optimization to place starting values for each chain near the posterior mode. We then ran 2,000–3,000 samples of burn-in, and generated at least 10,000 samples post-burn-in. Recovered posterior distributions, with prior distributions overlaid, are shown in Extended Data Fig. 1. We distinguished fitted models using the DIC criterion57.

Analysis of the stationary age distribution of cases

To infer the age-specific clinical fraction and susceptibility from reported case distributions, we assumed that reported cases follow the stationary distribution of cases reached in the early phase of an epidemic. Using our dynamic model would allow modeling any transient emphasis in the case distribution associated with the age of the individuals who seeded infection in a given region, but because the age of the true first cases is not generally known, we used the stationary distribution instead. Specifically, we used Bayesian inference to fit age-specific susceptibility and clinical fraction to the reported case distribution by first generating the expected case distribution ki from (1) the age-specific susceptibility ui, (2) the age-specific clinical fraction yi, (3) the measured or estimated contact matrix for the country and (4) the age structure of the country or region. We then used the likelihood

where ci is the observed case distribution, when fitting to data from a single country or region. When fitting to a combined set of regions and/or countries, we used the likelihood

across countries \(j \in \left\{ {1,2,...,m} \right\}\) with weights wj such that \(\mathop {\prod}\nolimits_j {w_j = 1}\). We weighted58 each of the 13 provinces of China in our dataset by 1/13, each of the 12 regions of Italy by 1/12, the three reported case distributions from China CDC by 1/3, and data from South Korea, Singapore, Japan and Ontario each by 1, then scaled all weights to multiply to 1. Above, QC is a fitted dispersion parameter to capture the variation in observed case distributions among countries.

The age-specific susceptibility ui and age-specific clinical fraction yi were estimated by evaluating the expected case distribution ci according to the likelihood functions given above. It is not possible to identify both ui and yi from case data alone. Accordingly, we inferred the age-specific clinical fraction, yi, from surveillance data from Italy reporting the age-specific number of cases that were asymptomatic, paucisymptomatic, mild, severe and critical19. We assumed that asymptomatic and paucisymptomatic infections may be underascertained relative to mild, severe and critical cases, and therefore estimated an ‘inflation factor’ z > 1 giving the number of unascertained asymptomatic or paucisymptomatic infections for each reported infection in these data. Accordingly, we applied the likelihood penalty

when fitting yi so as to constrain the relative shape of the clinical fraction curve by age. Here, mildi is the number of mild cases reported in age group i, sevi the number of severe cases in age group i and so on. Therefore the age-specific clinical fraction reflected the proportion of infections reported by Riccardo et al.19 as mild, critical or severe, relative to an estimated proportion of asymptomatic and paucisymptomatic infections. Above, QX is a fitted dispersion parameter to capture the variation in clinical fraction among countries.

To estimate a value for the inflation factor z compatible with empirical data on the severity of infections, we applied a further likelihood penalty when estimating the consensus fit for clinical fraction and susceptibility so as to match information on age-specific susceptibility collected from recent contact-tracing studies34,35,36,37. A leave-one-out analysis showed that these additional data allowed the model fitting procedure to converge on a consistent profile for both ui and yi (Extended Data Fig. 3).

We extracted age-specific case data from the following sources. For provinces of China, we used age-specific case numbers reported by China CDC1 as well as line list data compiled by the Shanghai Observer29. For regions of Italy, we used age-specific case numbers reported by the Istituto Superiore di Sanità on 13 March 202032. For South Korea, we used the line list released by Kim et al. based on data from the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention26. For Japan, we used the Open Covid Line List30,31. For Singapore, we used Singapore Ministry of Health data compiled by Koh25. For Ontario, we used data compiled by the COVID-19 Canada Open Data Working Group33.

To validate our line list analysis, we fitted the dynamic model to incidence data from Beijing, Shanghai, South Korea and Lombardy, Italy (Extended Data Fig. 5). We fixed the reporting rate for Beijing, Shanghai, South Korea and Lombardy to 20%. Beijing and Shanghai incidence data were given by case onset, so we assumed no delay between reported and true case onsets. Incidence data for South Korea were given by the date of confirmation only, and we assumed the reporting delay followed a gamma distribution with a 7-day mean. Incidence data for Italy were given separately for case onset and case confirmation, with only a subset of onset dates available; accordingly, we fit the proportion of confirmed cases with onset dates and the delay from onset to confirmation. We adjusted the size parameter of the negative binomial distribution used to model case incidence to 10 to reflect greater variability among fewer data points for these countries than for Wuhan. Beijing and Shanghai were fitted jointly, with separate dates of introduction but the same fitted susceptibility, large-scale restriction date and large-scale restriction magnitude. South Korea and Italy were each fitted separately; we fitted a large-scale restriction date and magnitude for both South Korea and Italy.

For both the line list fitting and validation, we assumed that schools were closed in China, but remained open in South Korea, Japan, Italy, Singapore and Canada, as schools were open for the majority of the period covered by the data in the latter five countries.

Quantifying the impact of school closure

To determine the impact in other cities with different demographic profiles we used the inferred parameters from our line list analysis to parameterize our transmission model for projections to other cities. We chose these to compare projections for a city with a high proportion of elderly individuals (Milan, Italy), a moderately aged population (Birmingham, UK) and a city in a low-income country with a high proportion of young individuals (Bulawayo, Zimbabwe). For this analysis, we compared an outbreak of COVID-19, for which the burden and transmission is concentrated in relatively older individuals, with an outbreak of pandemic influenza, for which the burden and transmission is concentrated in relatively younger individuals. We assumed that immunity to influenza builds up over a person’s lifetime, such that an individual’s susceptibility to influenza infection plateaus at roughly age 35 years, and assumed that the severity of influenza infection is highest in the elderly and in children under 10 years old44.

To model Milan, we used the age distribution of Milan in 201959 and a contact matrix measured in Italy in 200611. To model Birmingham, we used the age distribution of Birmingham in 201860 and a contact matrix measured in the UK in 200611. To model Bulawayo, we used the age distribution of Bulawayo Province in 201261 and a contact matrix measured in Manicaland, Zimbabwe in 201362. We assumed that the epidemic was seeded by two infectious individuals in a random age group per week for five weeks. We scaled the age-specific susceptibility ui by setting the ‘target’ basic reproductive number, R0 = 2.4, as a representative example. We also performed a sensitivity analysis where we scaled ui to result in R0 = 2.4 in Birmingham, using the same setting for ui in all three cities, so that the actual R0 changed depending upon the contact matrices and demographics used to model each city. This produced qualitatively similar results (Extended Data Fig. 9).

We projected the impact of school closure by setting the contact multiplier for school contacts, school(t), to 0. Complete removal of school contacts may overestimate the impact of school closures because of alternate contacts children make when out of school63. This will, however, give the maximum impact of school closures in the model to demonstrate the differences.

Projecting the global impact

To project the impact of COVID-19 outbreaks in global cities, we used mixing matrices from Prem et al.38 and demographic structures for 2020 from World Population Prospects 2019 to simulate a COVID-19 outbreak in 146 global capital cities for which synthetic matrices, demographic structures and total populations were available. For simplicity, we assumed that capital cities followed the demographic structure of their respective countries and took the total population of each capital city from the R package maps. For each city, we scaled ui to result in an average R0 = 2.4 in Birmingham, UK, and used the same setting for ui for all cities, so that the realized R0 would change according to the contact matrices and demographics for each city. We simulated 20 outbreaks in each city, drawing the age-specific clinical fraction yi from the posterior of the estimated overall clinical fraction from our line list analysis (Fig. 2), and analyzed the time to the peak incidence of the epidemic, the peak clinical and subclinical incidence of infection and the total number of clinical and subclinical infections. We took the first third and the last third of clinical cases in each city to compare the early and late stages of the epidemic.

Contact matrices

Wherever possible, we used measured contact matrices (Supplementary Table 3). We adapted each of these mixing matrices, using 5-year age bands, to specific regions of the countries in which they were measured by reprocessing the original contact surveys with the population demographics of the local regions. The contact matrices we used for Figs. 1–3 are shown in Extended Data Fig. 10.

The contact survey in Shanghai64 allowed respondents to record both individual (one-on-one) and group contacts, the latter with approximate ages. Although individual contacts were associated with a context (home, work, school and so on), group contacts were not, and so we assumed that all group contacts that involved individuals aged 0–19 years occurred at school. We also assumed that group contacts were lower intensity than individual contacts, weighting group contacts by 50% relative to one-on-one contacts.

We assumed schools were closed during the epidemic in China (because schools closed for the Lunar New Year holiday and remained closed), but open in Italy, Singapore, South Korea, Japan and Canada, because we used data from the early part of the epidemics in those countries, at which time schools were open.

Sensitivity analyses

Because the infectiousness of subclinical individuals was not identifiable from the data we have available, in Fig. 2 we adopted a baseline estimate of 50% relative to preclinical and clinical individuals. In Extended Data Fig. 7, we performed sensitivity analysis by repeating our model runs with the alternate values for subclinical infectiousness between 0% and 100%. We did not find a marked difference in the findings or estimates.

In Fig. 2 we fitted the age distributions of cases in six countries jointly to findings from recent studies on the susceptibility of children. We tested the sensitivity of our findings to the findings of the other studies by conducting a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis. The results are provided in Extended Data Fig. 3, and we did not find major changes to the shape of the age dependence in either susceptibility or clinical fraction.

In Fig. 3, we show the epidemic in three cities with fixed R0 of 2.4 to illustrate the effect that demographics alone have on the effectiveness of interventions. This means that the higher rates of contact measured in surveys in Milan and Bulawayo compared with Birmingham were not included. We also tested the sensitivity of findings on school closure. for which we fixed susceptibility ui and thus R0 varied (Extended Data Fig. 9). The conclusions regarding the relative effectiveness of school closures for COVID-19 versus influenza are similar.

In Fig. 4 we assumed that the age-specific clinical fraction was the same across all settings, but we tested the sensitivity of our projections (Fig. 4) to the age-specific clinical fraction used in lower-income countries. However, a higher rate of comorbidities in lower-income countries could change the age-specific probability of developing clinical symptoms upon infection. To investigate this possibility, we constructed a schematic alternate age-specific profile of clinical fraction by (1) increasing the age-specific probability of developing symptoms by 15% for individuals under the age of 20 years and (2) shifting the age-specific clinical fraction for individuals over the age of 20 years by 10 years older (Extended Data Fig. 6). We repeated the analyses with these functions and found increased burden in lower-income countries, which could exceed the burden of clinical cases in higher-income countries.

Finally, we repeated our projections for country-specific burdens of COVID-19 assuming different values for the relative infectiousness of subclinical infections. We found that this had a small effect on the relationship between median age and case burden across countries (Extended Data Fig. 8).

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this Article.

Data availability

The data used for fitting are publicly available and are available with the code.

Code availability

All code is available in the GitHub repository for the project at https://github.com/cmmid/covid-age. Contact matrix data are available at Zenodo21,22.

References

Liu, Z., Xing, B. & Xue Za, Z. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China. Chin. J. Epidemiol. 41, 145–151 (2020).

Sun, K., Chen, J. & Viboud, C. Early epidemiological analysis of the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak based on crowdsourced data: a population-level observational study. Lancet Digit. Health 2, e201–e208 (2020).

Cereda, D. et al. The early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in Lombardy, Italy. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/pdf/2003.09320.pdf (2020).

Shim, E., Tariq, A., Choi, W., Lee, Y. & Chowell, G. Transmission potential and severity of COVID-19 in South Korea. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 93, 339–344 (2020).

Dong, Y. et al. Epidemiological characteristics of 2,143 pediatric patients with 2019 coronavirus disease in China. Pediatrics 145, e20200702 (2020).

Zhao, X. et al. Incidence, clinical characteristics and prognostic factor of patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Preprint at http://medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2020.03.17.20037572 (2020).

Anderson, R. M. et al. Epidemiology, transmission dynamics and control of SARS: the 2002–2003 epidemic. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 359, 1091–1105 (2004).

Lipsitch, M., Swerdlow, D. L. & Finelli, L. Defining the epidemiology of Covid-19—studies needed. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1194–1196 (2020).

Nickbakhsh, S. et al. Epidemiology of seasonal coronaviruses: establishing the context for the emergence of coronavirus disease 2019. J. Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiaa185 (2020).

Kissler, S. M., Tedijanto, C., Goldstein, E., Grad, Y. H. & Lipsitch, M. Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period. Science 368, 860–868 (2020).

Huang, A. T. et al. A systematic review of antibody mediated immunity to coronaviruses: antibody kinetics, correlates of protection and association of antibody responses with severity of disease. Preprint at http://medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2020.04.14.20065771 (2020).

Cowling, B. J. et al. Increased risk of noninfluenza respiratory virus infections associated with receipt of inactivated influenza vaccine. Clin. Infect. Dis. 54, 1778–1783 (2012).

Tsagarakis, N. J. et al. Age-related prevalence of common upper respiratory pathogens, based on the application of the FilmArray Respiratory panel in a tertiary hospital in Greece. Medicine (Baltim.) 97, e10903 (2018).

Common Cold (NHS, 2017); https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/common-cold/

Zhang, J. et al. Changes in contact patterns shape the dynamics of the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Science (in the press); https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb8001

Bi, Q. et al. Epidemiology and transmission of COVID-19 in 391 cases and 1286 of their close contacts in Shenzhen, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. (in the press); https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30287-5

Galanti, M. et al. Rates of asymptomatic respiratory virus infection across age groups. Epidemiol. Infect. 147, e176 (2019).

Zhou, F. et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 395, 1054–1062 (2020).

Riccardo, F. et al. Epidemiological characteristics of COVID-19 cases in Italy and estimates of the reproductive numbers one month into the epidemic. Preprint at http://medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2020.04.08.20056861 (2020).

Van Kerckhove, K., Hens, N., Edmunds, W. J. & Eames, K. T. D. The impact of illness on social networks: implications for transmission and control of influenza. Am. J. Epidemiol. 178, 1655–1662 (2013).

Mossong, J. et al. Social contacts and mixing patterns relevant to the spread of infectious diseases. PLoS Med. 5, e74 (2008).

Cauchemez, S., Valleron, A.-J., Boëlle, P.-Y., Flahault, A. & Ferguson, N. M. Estimating the impact of school closure on influenza transmission from Sentinel data. Nature 452, 750–754 (2008).

Eames, K. T. D., Tilston, N. L., Brooks-Pollock, E. & Edmunds, W. J. Measured dynamic social contact patterns explain the spread of H1N1v influenza. PLoS Comput. Biol. 8, e1002425 (2012).

Huang, C. et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395, 497–506 (2020).

Koh, A. Singapore COVID-19 Cases (2020); http://alexkoh.net/covid19/ (accessed 4 March 2020).

Data Science for COVID-19 (DS4C) (2020); https://kaggle.com/kimjihoo/coronavirusdataset (accessed 13 March 2020).

Li, Q. et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1199–1207 (2020).

Yang, Y. et al. Epidemiological and clinical features of the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in China. Preprint at http://medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2020.02.10.20021675 (2020).

Shanghai Observer. COVID-2019 Linelist (2020); http://data.shobserver.com/www/datadetail.html?contId=1000895 (accessed 10 Feb 2020).

COVID19_2020_open_line_list (2020); https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1itaohdPiAeniCXNlntNztZ_oRvjh0HsGuJXUJWET008/edit?usp=sharing (accessed 1 March 2020).

Xu, B. et al. Open access epidemiological data from the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20, 534 (2020).

Bolletino Sorveglianza Integrata COVID-19 12 Marzo 2020 Appendix (Epicentro, 2020); https://www.epicentro.iss.it/coronavirus/bollettino/Bolletino-sorveglianza-integrata-COVID-19_12-marzo-2020_appendix.pdf

COVID-19 in Canada (2020); https://art-bd.shinyapps.io/covid19canada/ (accessed 21 March 2020).

Zhang, J. et al. Changes in contact patterns shape the dynamics of the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Science (in the press); https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb8001

Gudbjartsson, D. F. et al. Spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the Icelandic population. N. Engl. J. Med. (in the press); https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2006100

Lavezzo, E. et al. Suppression of COVID-19 outbreak in the municipality of Vo, Italy. Preprint at https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.17.20053157v1 (2020).

Chau, N. V. V. et al. The natural history and transmission potential of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Preprint at http://medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2020.04.27.20082347 (2020).

Prem, K., Cook, A. R. & Jit, M. Projecting social contact matrices in 152 countries using contact surveys and demographic data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005697 (2017).

Onder, G., Rezza, G. & Brusaferro, S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA 323, 1775–1776 (2020).

Chan, K. P. Control of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Singapore. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 10, 255–259 (2005).

Lau, J. T. F. Monitoring community responses to the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong: from day 10 to day 62. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 57, 864–870 (2003).

Cauchemez, S. et al. School closures during the 2009 influenza pandemic: national and local experiences. BMC Infect. Dis. 14, 207 (2014).

Cauchemez, S. et al. Closure of schools during an influenza pandemic. Lancet Infect. Dis. 9, 473–481 (2009).

Greer, A. L., Tuite, A. & Fisman, D. N. Age, influenza pandemics and disease dynamics. Epidemiol. Infect. 138, 1542–1549 (2010).

Viner, R. M. et al. School closure and management practices during coronavirus outbreaks including COVID-19: a rapid systematic review. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 4, 397–404 (2020).

Clark, A. et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of the population at increased risk of severe COVID-19 due to underlying health conditions in 2020: a modelling study. Lancet Glob. Health (in the press).

Cohen, C. et al. Severe influenza-associated respiratory infection in high HIV prevalence setting, South Africa, 2009–2011. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 19, 1766–1774 (2013).

Ludvigsson, J. F. Systematic review of COVID‐19 in children shows milder cases and a better prognosis than adults. Acta Paediatr. 109, 1088–1095 (2020).

Williams, C. M. et al. Exhaled Mycobacterium tuberculosis output and detection of subclinical disease by face-mask sampling: prospective observational studies. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20, 607–617 (2020).

Global Burden of Disease (IHME, 2020); http://www.healthdata.org/gbd

Murray, J. et al. Determining the provincial and national burden of influenza-associated severe acute respiratory illness in South Africa using a rapid assessment methodology. PLoS ONE 10, e0132078 (2015).

Liu, Y. et al. Active or latent tuberculosis increases susceptibility to COVID-19 and disease severity. Preprint at http://medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2020.03.10.20033795 (2020).

Cohen, A. L. et al. Potential impact of co-infections and co-morbidities prevalent in Africa on influenza severity and frequency: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 10, e0128580 (2015).

Docherty, A. B. et al. Features of 16749 hospitalised UK patients with COVID-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol. Preprint at http://medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2020.04.23.20076042 (2020).

China Statistical Year Book (2005–2018) (National Bureau of Statistics, 2020); http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/

Braak, C. J. F. T. A Markov Chain Monte Carlo version of the genetic algorithm Differential Evolution: easy Bayesian computing for real parameter spaces. Stat. Comput. 16, 239–249 (2006).

Spiegelhalter, D. J., Best, N. G., Carlin, B. P. & van der Linde, A. Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 64, 583–639 (2002).

Varin, C., Reid, N. & Firth, D. An overview of composite likelihood methods. Statistica Sinica 21, 5–42 (2011).

Milano (Metropolitan City, Italy)—Population Statistics, Charts, Map and Location (2020); http://citypopulation.info/en/italy/admin/lombardia/015__milano/ (accessed 15 March 2020).

Age Breakdown of the Population of Birmingham (Office for National Statistics, 2020); https://www.ons.gov.uk/aboutus/transparencyandgovernance/freedomofinformationfoi/agebreakdownofthepopulationofbirmingham (accessed 15 March 2020).

Bulawayo (City, Zimbabwe)—Population Statistics, Charts, Map and Location (2020); http://citypopulation.info/php/zimbabwe-admin.php?adm1id=A (accessed 15 March 2020).

Melegaro, A. et al. Social contact structures and time use patterns in the manicaland province of Zimbabwe. PLoS ONE 12, e0170459 (2017).

Kucharski, A. J., Conlan, A. J. K. & Eames, K. T. D. School’s out: seasonal variation in the movement patterns of school children. PLoS ONE 10, e0128070 (2015).

Zhang, J. et al. Patterns of human social contact and contact with animals in Shanghai, China. Sci. Rep. 9, 15141 (2019).

Acknowledgements

N.G.D. acknowledges funding from the National Institutes of Health Research (HPRU-2012-10096). P.K., Y.L., K.P. and M.J. acknowledge partial funding by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (INV-003174). This work was funded in part by the Royal Society under award no. RP\EA\180004 (P.K.). Y.L. and M.J. acknowledge partial funding by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) (16/137/109) using UK aid from the UK Government to support global health research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the UK Department of Health and Social Care. R.M.E. acknowledges funding from HDR UK (grant no. MR/S003975/1) and MRC (grant no. MC_PC 19065). The members of the CMMID COVID-19 working group acknowledge funding as follows: C.A.B.P. and BJ.Q. (NIHR 16/137/109), A.J.K. (Wellcome Trust grant no. 206250/Z/17/Z), H.G. (funded by the Department of Health and Social Care using UK Aid funding and managed by the NIHR; the views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Department of Health and Social Care (ITCRZ 03010)), S.C. (Wellcome Trust grant no. 208812/Z/17/Z), A.G. (Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) for the project ‘RECAP’ managed through RCUK and ESRC (ES/P010873/1)), K.v.Z. (supported by Elrha’s Research for Health in Humanitarian Crises (R2HC) Programme, which aims to improve health outcomes by strengthening the evidence base for public health interventions in humanitarian crises; the R2HC programme is funded by the UK Government (DFID), the Wellcome Trust and the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)), J.D.M. (Wellcome Trust grant no. 210758/Z/18/Z), C.D. (NIHR 16/137/109), W.J.E. and J.H. (Wellcome Trust grant no. 210758/Z/18/Z), T.W.R. (Wellcome Trust grant no. 206250/Z/17/Z), S.A. (Wellcome Trust grant no. 210758/Z/18/Z), S.F. (Wellcome Trust grant no. 210758/Z/18/Z), N.I.B. and Y.F.S. (NIHR EPIC grant no. 16/137/109), S.F. (Wellcome Trust grant no. 208812/Z/17/Z), A.R. (NIHR grant no. PR-OD-1017-20002), C.I.J. (Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) project ‘RECAP’ managed through RCUK and ESRC (ES/P010873/1)) and R.M.G.J.H. (European Research Commission Starting Grant no. 757699).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

R.M.E. conceived the study. N.G.D. and R.M.E. designed the model with P.K., and Y.L., K.P. and M.J. providing input. N.G.D. designed the software and inference framework and implemented the model. Y.L. processed the data. N.G.D. and R.M.E. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors interpreted the results, contributed to writing and approved the final version for submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Jennifer Sargent was the primary editor on this article and managed its editorial process and peer review in collaboration with the rest of the editorial team.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Posterior distributions for Wuhan.

Prior distributions (gray dotted lines) and posterior distributions (colored histograms) for model parameters fitting to the early epidemic in Wuhan (Fig. 1, main text); seed_start is measured in days after November 1st, 2019. a, Model 1 (age-varying contact patterns and susceptibility); b, Model 2 (age-varying contact patterns and clinical fraction); c, Model 3 (age-varying contact patterns only). See also Supplementary Table 4.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Simultaneous estimation of age-varying susceptibility and clinical fraction to epidemic data from Wuhan City, China.

This figure replicates Fig. 1 of the main text, but comparing model variants 1 and 2 to a fourth model variant in which both susceptibility and clinical fraction vary by age. a, Model diagram (see Fig. 1, main text). b, Susceptibility by age for the three models. Age-specific values were estimated for models 1 (orange) and 4 (pink). Susceptibility is defined as the probability of infection on contact with an infectious person. Mean (lines), 50% (darker shading) and 95% (lighter shading) credible intervals shown. c, Clinical fraction (yi) by age for the three models. Age-specific values were estimated for model 2 (blue) and 4 (pink), and fixed at 0.5 for model 1. d, Fitted contact multipliers for holiday (qH) and restricted periods (qL) for each model showed an increase in non-school contacts beginning on January 12th (start of Lunar New Year) and a decrease in contacts following restrictions on January 23rd. e, Estimated R0 values for each model. The red barplot shows the inferred window of spillover of infection. f, Incident reported cases (black), and modeled incidence of reported clinical cases for the three models fitted to cases reported by China Centers for Disease Control (CCDC) with onset on or before February 1st, 2020. Line marks mean and shaded window is the 95% highest density interval (HDI). g, Age distribution of cases by onset date as fitted to the age distributions reported by Li et al. (first three panels) and CCDC (fourth panel). Data are shown in the hollow bars, and model predictions in filled bars, where the dot marks the mean posterior estimate. h, Implied distribution of subclinical cases by age for each model. Credible intervals on modeled values show the 95% HDIs; credible intervals on data for panels g and h show 95% HDIs for the proportion of cases in each age group.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Impact of data sources used.

Analysis showing how the inferred age-varying susceptibility (first column) and age-varying clinical fraction (second column) depend upon the additional data sources used.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Posterior estimates for the consensus susceptibility and clinical fraction from 6 countries.

Note that susceptibility is a relative measure.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Posterior distributions for Beijing, Shanghai, South Korea, and Lombardy.

Prior and posterior distributions for the epidemics in a, Beijing and Shanghai, b, South Korea and c, Lombardy using the ‘consensus’ fit for age-specific clinical fraction and assuming subclinical infections are 50% as infectious as clinical infections (see Fig. 2c, main text). For (a), times are in days after December 1st, 2019; for (b) and (c), times are in days after January 1st, 2019. Note, seed_d is the inferred duration of the seeding event. See also Supplementary Table 4.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Global projections assuming greater severity in lower-income countries.

a, Schematic age-specific clinical fraction for higher-income and lower-income countries. b-f, Illustrative results of the projections for 146 capital cities assuming a higher age-varying clinical fraction in lower-income countries. See Fig. 4 (main text) for details.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Consensus age-specific clinical fraction and susceptibility under varying assumptions for subclinical infectiousness.

Line and ribbons show mean and 95% HDI for clinical fraction and susceptibility, assuming subclinical infections are 0%, 25%, 50%, 75%, or 100% as infectious as clinical infections.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Projections for capital cities depending upon subclinical infectiousness.

a, Projected total and peak clinical case attack rate for 146 capital cities, under different assumptions for the infectiousness of subclinical infections. b, Projected total and peak subclinical infection attack rate for 146 capital cities, under different assumptions for the infectiousness of subclinical infections. c, Projected differences in R0 among 146 capital cities, under different assumptions for the infectiousness of subclinical infections. Mean and 95% HDI shown.

Extended Data Fig. 9 School closures with fixed susceptibility across cities.

Comparison of school closures in three exemplar cities when susceptibility ui is fixed across settings instead of R0. See main text Fig. 3 for details.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1–4.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Davies, N.G., Klepac, P., Liu, Y. et al. Age-dependent effects in the transmission and control of COVID-19 epidemics. Nat Med 26, 1205–1211 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0962-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0962-9