Abstract

Zoonotic coronaviruses (CoVs) are substantial threats to global health, as exemplified by the emergence of two severe acute respiratory syndrome CoVs (SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2) and Middle East respiratory syndrome CoV (MERS-CoV) within two decades1,2,3. Host immune responses to CoVs are complex and regulated in part through antiviral interferons. However, interferon-stimulated gene products that inhibit CoVs are not well characterized4. Here, we show that lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus E (LY6E) potently restricts infection by multiple CoVs, including SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV. Mechanistic studies revealed that LY6E inhibits CoV entry into cells by interfering with spike protein-mediated membrane fusion. Importantly, mice lacking Ly6e in immune cells were highly susceptible to a murine CoV—mouse hepatitis virus. Exacerbated viral pathogenesis in Ly6e knockout mice was accompanied by loss of hepatic immune cells, higher splenic viral burden and reduction in global antiviral gene pathways. Accordingly, we found that constitutive Ly6e directly protects primary B cells from murine CoV infection. Our results show that LY6E is a critical antiviral immune effector that controls CoV infection and pathogenesis. These findings advance our understanding of immune-mediated control of CoV in vitro and in vivo—knowledge that could help inform strategies to combat infection by emerging CoVs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are enveloped RNA viruses with broad host tropism and documented capability to cross the species barrier to infect humans5. The mammalian innate immune response controls CoV infection partly through the action of interferons (IFNs)4,6,7. IFNs inhibit viral infection by inducing hundreds of genes, many of which encode antiviral effectors8. The IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) that inhibit CoV infection are not well defined4. To address this knowledge gap, we screened our published library of >350 human ISG complementary DNAs9,10 in human hepatoma cells for antiviral activity against the endemic human CoV 229E (HCoV-229E) (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). The ISG lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus E (LY6E) strikingly inhibited HCoV-229E infection (Fig. 1a,b and Extended Data Fig. 1a). This was unexpected since we and others previously reported that LY6E enhances cellular infection by influenza A virus, flaviviruses and human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) (refs. 11,12,13), with HIV-1 being an exception, with opposing roles of LY6E described14. To verify this result, we generated stable cell lines ectopically expressing LY6E and infected cells with diverse CoVs. In addition to HCoV-229E (Fig. 1c), LY6E significantly reduced infection by HCoV-OC43 (Fig. 1d), Middle East respiratory syndrome CoV (MERS-CoV; Fig. 1e), severe acute respiratory syndrome CoV (SARS-CoV; Fig. 1f) and the recently emerged SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 1g and Extended Data Fig. 1b). The antiviral effect of LY6E extended beyond human CoVs and decreased infection by the murine CoV mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) (Fig. 1h). Given the zoonotic origin of MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, all of which are suspected to have originated from bats, we next tested the antiviral potential of select LY6E orthologues. All LY6E orthologues inhibited HCoV-229E (Extended Data Fig. 1c). Recent surveillance of Kenyan camels—the main viral reservoir for MERS-CoV—indicates active circulation of the zoonotic CoV13. Human and camel LY6E restricted MERS-CoV infection (Extended Data Fig. 1d). To confirm the presence of LY6E in respiratory cells that are targeted by human CoVs, we examined expression in primary human airway epithelial cells (hAECs) by single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). LY6E was widely expressed in all cell types, with the greatest levels observed in goblet cells (Fig. 1i). We additionally assessed the expression of known human CoV receptors in hAECs by scRNA-seq and observed broad expression of the HCoV-229E receptor CD13, the MERS-CoV receptor DPP4 and the SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 in multiple cell types (Extended Data Fig. 1e–g). Infection of hAECs with SARS-CoV-2, but not SARS-CoV, potently induced the expression of LY6E in hAECs at 3 d post-infection (Fig. 1j). LY6E has previously been shown to restrict HIV-1 infection by promoting internalization of the receptor CD4 (ref. 14). When we ectopically expressed angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in human hepatoma cells, SARS-CoV-2 infectivity increased, but LY6E still restricted SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 1k,l and Extended Data Fig. 1h). Importantly, total levels of ectopically expressed ACE2 were unaltered by LY6E expression (Extended Data Fig. 1i). Furthermore, LY6E expression had no effect on cell surface levels of other CoV receptors (that is, CD13 (Extended Data Fig. 1j) and DPP4 (Extended Data Fig. 1k)). Collectively, our data show that LY6E is a constitutively expressed ISG product that restricts infection by endemic and pandemic CoVs without modulating the expression of viral receptors.

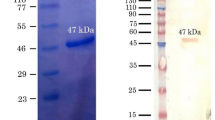

To test the role of endogenous LY6E in controlling CoV infections, we used CRISPR–Cas9 gene editing to ablate LY6E expression in human lung adenocarcinoma cells (Fig. 1m). This cell line was selected as human hepatoma cells do not express LY6E irrespective of IFN treatment11. LY6E knockout cells were more susceptible to HCoV-229E (Fig. 1n). Reconstitution with a CRISPR-resistant LY6E variant restored antiviral activity in knockout cells (Fig. 1o,p). Strikingly, the LY6E-mediated restriction in hepatoma cells was largely specific to CoVs. Among ten genetically divergent viruses tested, only hepatitis C virus was also restricted (Extended Data Fig. 1l).

a, Duplicate screens depicting HCoV-229E infection (24 h post-infection) in Huh7 cells ectopically expressing ISGs. b, HCoV-229E infection of Huh7 cells expressing LY6E or control vector (empty) (blue: DAPI; green: HCoV-229E N protein; red: TagRFP encoded in SCRPSY vector). c–h, Effect of stable LY6E expression on diverse CoVs. Cells were infected with HCoV-229E (c), HCoV-OC43 (d), MERS-CoV (e), SARS-CoV (f), SARS-CoV-2 (g) or MHV-Gluc (h). RLU, relative light units. i, Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) visualization of LY6E expression and distribution in primary hAEC cultures from two donors by scRNA-seq. j, Induction of LY6E in mock or infected hAECs from three donors by RNA-seq. k, SARS-CoV-2 infection of LY6E or control vector (FLuc) Huh7.5 cells co-expressing human ACE2 (blue: DAPI; green: SARS-CoV-2 dsRNA; red: TagRFP encoded in SCRPSY-ACE2 vector). l, Quantification of the dsRNA mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) normalized by the number of nuclei in the image. m, Western blot of wild-type (WT) A549 or two LY6E knockout (KO) clones (numbers 3 and 4). n, HCoV-229E infection of wild-type or LY6E knockout A549. o, Western blot of wild-type or LY6E knockout A549 reconstituted with CRISPR-resistant LY6E (CR LY6E) or control vector (empty). p, HCoV-229E infection of CRISPR-resistant LY6E-reconstituted wild-type or LY6E knockout A549. Data represent the means of independent biological replicates (n = 3 (c, d, f–h, j and l) and n = 4 (e, n and p)). Immunofluorescence images are depicted exemplarily from n = 2 (b) and n = 3 images (k). In l, seven images per condition were acquired and processed. Scale bars: 200 µM (b) and 100 µM (k). Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction (c, d, f and h), one-tailed Mann–Whitney U-test (e), two-tailed ratio-paired Student’s t-test (g), one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (l) or two-way ANOVA followed by Šidák’s or Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (n and p). For the box plots, centre lines indicate mean values, and upper and lower bounds, respectively, indicate maximum and minimum replicate values (j and l). Error bars represent s.d. P values: **P = 0.0088 (c); ***P = 0.0001 (d); *P = 0.0143 (e); *P = 0.0286 (f); *P = 0.0101 (g); ***P = 0.0010 (h); **P = 0.0035, **P = 0.0091 and **P = 0.0057 (left to right in l); **P = 0.0073 and **P = 0.0033 (left to right in n); and **P = 0.0013 and ***P = 0.0001 (left to right in p). NS, not significant.

LY6E is a member of the LY6/uPAR family of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins, and is implicated in diverse cellular processes15. To evaluate the specificity of LY6E for inhibiting CoVs, we ectopically expressed selected LY6/uPAR proteins11 and infected Huh7 cells with HCoV-229E. Only LY6E inhibited CoV infection (Extended Data Fig. 1m). We previously showed that a conserved residue (L36) is required for LY6E-mediated enhancement of influenza A virus11. L36 was also required to restrict HCoV-229E infection (Extended Data Fig. 1n). These data suggest a conserved functional domain that is responsible for both the virus-enhancing and virus-restricting phenotypes.

Next, we investigated the effect of LY6E on specific steps of the virus replication cycle. First, we tested whether LY6E restricts CoV attachment to the cell surface, and observed no effect on HCoV-229E binding (Extended Data Fig. 2a). To test whether LY6E restricts viral entry, we used a vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) pseudoparticle system bearing CoV spike proteins. Strikingly, LY6E significantly inhibited VSV pseudoparticle entry mediated by spike proteins from HCoV-229E (Fig. 2a), MERS-CoV (Fig. 2a), SARS-CoV (Fig. 2b) and SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 2b). Entry mediated by VSV glycoprotein G (VSV-G) was not affected by LY6E (Fig. 2a,b). Time-course experiments revealed that LY6E had no effect on CoV translation, replication, assembly or release, as assessed with HCoV-229E (Extended Data Fig. 2b–f). To further narrow down the entry phenotype, we tested whether LY6E interferes with the fusion of viral and cellular membranes. To this end, we performed a syncytia formation assay using propagation-competent VSV pseudoviruses co-expressing CoV spike protein and a green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter (VSV*ΔG(CoV S)) (Extended Data Fig. 3a). LY6E potently inhibited CoV spike protein-mediated syncytia formation (Fig. 2c,d). To determine whether LY6E impairs spike protein expression or maturation, we also performed a heterologous syncytia formation assay. CoV-resistant hamster cells infected with the trans-complemented GFP reporter VSV*ΔG(CoV) were co-cultured with susceptible target cells that ectopically expressed LY6E. LY6E again significantly blocked syncytia formation, demonstrating that LY6E inhibits spike protein-mediated fusion and not spike protein expression or maturation (Extended Data Fig. 3b,c). As membrane fusion can occur without syncytia formation, we also performed a quantitative fusion assay in which the mixing of cell contents results in complementation of split-luciferase/split-GFP (Fig. 2e–h). Cells co-transfected with plasmids encoding CoV spike proteins and split-GFP were mixed with susceptible target cells co-expressing LY6E or vector control and the complementary fragment of split-GFP. LY6E reduced CoV S-mediated cell–cell fusion of HCoV-229E (Fig. 2e,f), MERS-CoV (Fig. 2e,f) and SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 2g,h), as visualized by a reduction of GFP-positive syncytia, indicating that LY6E blocks the fusion of viral and cellular membranes. Importantly, no effect on control cells (mCherry-transfected or VSV-G) could be observed (Fig. 2e–h). SARS-CoV did not induce cell–cell fusion in this experimental setup, consistent with recent observations (Fig. 2g,h)16,17. Collectively, our results demonstrate that LY6E specifically inhibits CoV spike protein-mediated membrane fusion, which is required for productive viral entry.

a,b, VSV pseudoparticles (PPs) harbouring spike proteins from HCoV-229E, MERS-CoV and G protein from VSV (a) or SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 and G protein from VSV (b) were inoculated on LY6E- or empty vector-expressing cells. The virus entry efficiency was quantified by measuring the virus-encoded luciferase reporter activity. c, VSV pseudoparticles expressing VSV-G protein on their surface and encoding CoV spike protein and GFP (VSV*∆G(CoV S)) were inoculated with LY6E- or empty vector-expressing Huh7. Syncytia formation was analysed by immunofluorescence microscopy (blue: DAPI; green: GFP; red: TagRFP inserted in SCRPSY vector). d, Quantification of VSV*∆G(CoV S)-induced syncytia, depicted as the percentage syncytia area. Three independent areas were analysed per biological replicate (circles, squares and triangles, respectively). e–h, Cell–cell fusion was analysed by co-incubating cells transfected with plasmids encoding mCherry, VSV-G protein or CoV spike proteins and a split-luciferase/split-GFP construct together with CoV-permissive LY6E-expressing or control cells transfected with the complementary fragment of split-luciferase/split-GFP. GFP complementation was analysed via immunofluorescence microscopy of GFP-positive syncytia. In e and g, an exemplary image of GFP-positive syncytia is depicted. f,h, Quantification of GFP-positive syncytia. Four images per condition were acquired and processed. Data were normalized to empty controls and are depicted as fold changes in mean GFP expression. Data represent the means of independent biological replicates (n = 8 for HCoV-229E S and MERS-CoV-S, n = 9 for VSV-G) (a); n = 6 (b); n = 3 (d); and n = 3 (f and h)). Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA followed by Šidák’s multiple comparisons test (a–d, f and h). Scale bars: 20 µM (c) and 50 µM (e and g). Error bars represent s.d. (a, b, d, f and h). P values: ****P = 3.3 × 10−16 and ****P = 3.6 × 10−15 (left to right in a); ****P = 1.363 × 10−6 and ****P = 4.200 × 10−14 (left to right in b); ****P = 6.0 × 10−9 and ****P < 1.1 × 10−15 (left to right in d); ***P = 0.0008 (f); and ***P = 0.0008 (h).

Next, we addressed whether LY6E influences proteolytic activation of the spike protein. After spike protein-mediated binding to the respective receptor, host proteases cleave the spike protein, activating membrane fusion18 at cell surfaces or within endosomes19. Inhibitors of cell surface and endosomal proteases suppressed infection but had no effect on LY6E-mediated restriction of CoV infection (Extended Data Fig. 4a–c). Proteolytic activation is also suppressed by cleavage site mutations19,20. Mutation of S1/S2 and S2′ in the spike protein of MERS-CoV reduced activation (Extended Data Fig. 4d)19,20. LY6E overexpression did not affect S1/S2 cleavage (Extended Data Fig. 4e,f) and did not affect the level of mutant MERS-CoV S pseudoparticle cell entry (Extended Data Fig. 4g). Collectively, our data indicate that restriction of viral fusion is independent of spike protein activation.

Next, we aimed to evaluate LY6E-mediated CoV restriction in vivo. Systemic genetic ablation of Ly6e in mice is embryonic lethal21. Therefore, we generated transgenic Ly6efl/fl mice, which are functionally wild type for Ly6e expression, and crossed them with Vav1-iCre mice to ablate Ly6e in immune cells that originate from a haematopoietic stem cell (HSC) progenitor (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b). This genetic model was chosen since immune cells are critical for protection from CoVs in vivo7,22,23,24,25,26. Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) from Ly6eΔHSC mice had reduced Ly6e messenger RNA levels (Extended Data Fig. 5c). The natural mouse pathogen MHV is a well-studied CoV model that causes hepatitis and encephalomyelitis in mice27. Ly6eΔHSC BMDMs were more susceptible to MHV infection than Ly6efl/fl BMDMs, demonstrating that murine Ly6e is a restriction factor for murine CoV (Extended Data Fig. 5d).

To determine whether Ly6e is important for controlling CoV infection in vivo, Ly6efl/fl and Ly6eΔHSC mice were infected with a high dose (5 × 104 plaque-forming units (p.f.u.)) of MHV that causes sub-lethal hepatitis in wild-type C57BL/6J mice28. Since MHV pathogenesis is influenced by sex, with higher levels of viral replication and hepatic damage observed in male mice29, we performed independent experiments in male and female mice. Ly6eΔHSC mice of both sexes rapidly succumbed to MHV infection by day 6 (Fig. 3a,b and Extended Data Fig. 6a,b). To examine viral pathogenesis and immunopathology in infected mice, Ly6efl/fl and Ly6eΔHSC mice were infected with the same high dose of MHV and euthanized 3 or 5 d post-infection. At both time points, female Ly6eΔHSC mice exhibited significantly higher levels of liver damage, as measured by serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), while no difference was observed in male mice (Fig. 3c,i and Extended Data Fig. 6c,i). However, hepatic viral burden did not differ in either sex (Fig. 3d,j and Extended Data Fig. 6d,j), possibly due to tissue saturation at this high dose. At a lower dose of MHV (5 p.f.u.), viral burden and liver damage were elevated in female mice, but not in male mice, which exhibited saturated hepatic infection, probably due to increased susceptibility, as previously reported (Extended Data Fig. 7a,b,f,g)29. Spleen viral burden was elevated in female and male Ly6eΔHSC mice at both time points and both doses of MHV (Fig. 3e,k and Extended Data Figs. 6e,k and 7c,h). At 3 d post-infection, there was no difference in liver necrosis, but inflammation was moderately reduced in female but not male Ly6eΔHSC mice (Fig. 3f–h and Extended Data Fig. 6f–h). By 5 d post-infection and at both low and high doses of MHV, female Ly6eΔHSC mice had significantly higher levels of liver necrosis and a reduced presence of mononuclear immune cells (Fig. 3l–n and Extended Data Fig. 7d,e), whereas no difference was observed in male mice (Extended Data Figs. 6l–n and 7i,j). Liver damage in Ly6eΔHSC mice was further corroborated at an intermediate viral dose (5 × 103 p.f.u.), which resulted in visibly apparent brittleness, pallor and necrotic foci (Extended Data Fig. 7k–n). These data show that Ly6e in HSCs is important for controlling murine CoV infection.

a,b, Female Ly6efl/fl and Ly6eΔHSC mice were injected with PBS or 50,000 p.f.u. MHV-A59 and monitored for survival (a) and weight loss (b). c–n, Mice were assessed at 3 (c–h) or 5 d post-infection with 50,000 p.f.u. MHV-A59 (i–n) for serum ALT (c and i), viral titres in the liver (d and j) and spleen (e and k), liver necrosis (f and l) and inflammation (g and m). Images of liver sections demonstrating necrosis inflammation are shown in h and n. In a and b, n = 13 for days 0–14 (for Ly6efl/fl), and n = 11 for days 0–3, n = 10 for days 4–5, n = 5 for day 6 and n = 3 for days 7–14 (for Ly6eΔHSC), from three pooled experiments. In c–g, data represent the means of n = 9 (Ly6efl/fl), n = 10 (Ly6eΔHSC) and n = 6 mice (PBS), from two pooled experiments. The images in h are representative of the same cohorts. In i–m, data represent the means of n = 9 (Ly6efl/fl), n = 7 (Ly6eΔHSC) and n = 6 mice (PBS), from two pooled experiments. Images in n are representative of the same cohorts. In h and n, scale bars are 500 µM (4×) and 100 µM (20×). Statistical significance was determined by two-sided Mantel–Cox test (a), two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction (c–e and i–k) and two-tailed Mann–Whitney U-test (f, g, l and m). Data are presented as means ± s.e.m. (b) or s.d. (c–g and i–m). P values: ***P = 0.0002 (a); **P = 0.0031 (c); ****P = 5.759 × 10−7 (e); **P = 0.0054 (g); *P = 0.0430 (i); **P = 0.0094 (k); **P = 0.0072 (l); and ****P = 8.741 × 10−5 (m).

Next, we used a transcriptomic approach to evaluate the effect of Ly6e ablation on global gene expression in the liver and spleen of female Ly6efl/fl and Ly6eΔHSC mice injected with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or the high dose of MHV at 3 and 5 d post-infection. In infected tissues, loss of Ly6e in HSCs correlated with differential gene expression in pathways associated with tissue damage, such as liver-specific metabolic genes, angiogenesis, wound healing and immune response to viruses (Fig. 4a–c). We also observed a striking loss of genes associated with the type I IFN response, inflammation, antigen presentation and B cells in livers and spleens from infected Ly6eΔHSC mice (Extended Data Figs. 7o,p and 8).

a–c, Transcriptomic analyses from female Ly6efl/fl (wild-type) and Ly6e∆HSC (knockout) mice. In a and b, heatmaps display significant changes (mean reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads > 0.5; fold change > 2; false discovery rate ≤ 0.05) in the liver (a) and spleen (b). The dendrograms use normalized read data (row z score) clustered with the complete linkage method employing Spearman’s rank correlation distance measurement. In c, a pathway analysis of the knockout versus the wild type is shown. Upregulated (red) and downregulated pathways (blue) are indicated by activation z score. The numbers show significantly dysregulated genes as the percentage of the total gene number included in the pathway. d,e, Immune cell counts from the liver (d) and spleen (e) of female mice infected with 5,000 p.f.u. MHV-A59, as measured at 5 d post-infection. f,g, Heatmaps of the average MHV-GFP infectivity of cultured splenocytes from female (f) and male mice (g) with two independent viral preparations shown. h,i, MHV-GFP infection of splenic B cells from females (h) and males (i), normalized to average (line at 100) of Ly6efl/fl mice. In a–c, n = 3. In d and e, n = 8 MHV-injected mice and n = 4 PBS-injected mice, from two pooled experiments. In f and h, n = 9 (Ly6efl/fl and Ly6eΔHSC) and n = 8 (Ifnar−/−) from four pooled experiments. In g and i, n = 9 (Ly6efl/fl) and n = 6 (Ly6eΔHSC and Ifnar−/−). Significance in d, e, h and i was determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. For the box plots, centre lines indicate means, and upper and lower bounds, respectively, indicate maximum and minimum replicate values (d and e). Error bars represent s.d. (h and i). P values (from left to right): ****P = 4.242 × 10−7, ***P = 8.902 × 10−4, ***P = 4.581 × 10−4, **P = 0.0030, *P = 0.0436, *P = 0.0381, *P = 0.0148, *P = 0.237 and *P = 0.0173 (d); ***P = 8.395 × 10−4, *P = 0.0414, *P = 0.0439, *P = 0.0233 and *P = 0.0295 (e); ****P = 1.1 × 10−14 and ****P = 1.2 × 10−14 (h); and ****P = 1.1416 × 10−9 and ****P = 1.0469 × 10−8 (i). GO, Gene Ontology; NA, not available; p.i., post-infection.

The histopathology (Fig. 3h,n) and transcriptome data (Fig. 4a–c and Extended Data Figs. 7o,p and 8) prompted us to determine how loss of Ly6e affects immune cell numbers during infection. Absolute numbers of different immune cell subsets were quantified in the spleen and liver from female and male Ly6eΔHSC and Ly6efl/fl mice 5 d after injection with PBS or the intermediate dose of MHV (Extended Data Fig. 9). In infected male mice, haematopoietic Ly6e protected hepatic B cells and recruited natural killer cells, dendritic cells, macrophages and neutrophils, but had no influence on CD8+ T cell recruitment (Extended Data Fig. 10a). Haematopoietic Ly6e in infected female mice protected hepatic B cells and CD4+ T cells and recruited natural killer cells (Fig. 4d). Multiple splenic cell populations were also altered with MHV infection in both male and female mice (Fig. 4e and Extended Data Fig. 10b). The depletion of immune cell populations in Ly6eΔHSC organs was MHV dependent, as cell numbers were similar between PBS-injected Ly6eΔHSC and Ly6efl/fl mice of both sexes.

To determine whether the loss of immune cells in MHV-infected Ly6eΔHSC mice correlates with increased permissiveness to infection, we assessed MHV infection in splenocytes cultured from Ly6eΔHSC, Ly6efl/fl and Ifnar−/− mice. In Ly6efl/fl splenocyte cultures, MHV infected macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells and B cells, but not CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, as previously reported (Fig. 4f,g)26. Strikingly, B cells from both male and female Ly6eΔHSC mice were highly susceptible to MHV infection compared with B cells from Ly6efl/fl mice (Fig. 4h,i). Antiviral protection from MHV was probably conferred by constitutive Ly6e expression, as B cells from Ifnar−/− mice showed similar resistance to MHV to cells from Ly6efl/fl mice. In female mice, only neutrophils from Ly6eΔHSC mice were more susceptible to MHV infection when compared with cells from Ifnar−/− but not Ly6efl/fl mice (Extended Data Fig. 10c). Dendritic cells and macrophages from male Ly6eΔHSC mice were also more susceptible to MHV infection than respective cells from Ly6efl/fl mice (Extended Data Fig. 10d). Surprisingly, no other cell type showed a strong Ly6e-dependent susceptibility to MHV infection.

Together, our data show an important role for Ly6e in immune cell-mediated control of CoV infection. Our observation of higher splenic viral burden and infection-associated alterations in hepatic and splenic cellular subsets indicates that mortality may be due to viral pathogenesis that exceeds the ability of the immune system to control the infection. Notably, we observed MHV-induced loss of three classes of cells in Ly6eΔHSC mice: (1) cells that are not permissive to the virus (CD4+ T cells); (2) cells that are permissive to MHV but do not demonstrate Ly6e knockout-dependent infection (natural killer cells); and (3) cells that are permissive to MHV in a Ly6e knockout-dependent manner (B cells, neutrophils, macrophages and dendritic cells). The increased susceptibility and reduction of Ly6e-deficient B cells suggest that lymphocytes may be key for restricting MHV replication and may possibly participate in downstream immune responses.

In conclusion, we identified LY6E as a CoV restriction factor that limits CoV entry and protects the host from severe viral disease. Our findings are striking given that LY6E has been primarily associated with an enhancing phenotype in which LY6E promotes entry of multiple viruses11,12,13. However, our data clearly expand the role of LY6E during CoV infection and establish a novel function in protecting the host immune cell compartment. Determining the precise molecular mechanism underlying how LY6E inhibits CoV spike protein-mediated membrane fusion will advance our understanding of cellular antiviral defences against these important human pathogens. Antiviral membrane fusion inhibitors have been successfully implemented for the treatment of HIV-1 infection30. A therapeutic approach mimicking the mechanism of action of LY6E could provide a first line of defence against novel emerging CoV infections. Furthermore, additional in vivo work will be needed to delineate which Ly6e-expressing immune cells protect mice from MHV, and for assessing the role of Ly6e during the pathogenesis of medically relevant human CoVs such as SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2.

Methods

Viral infection assays

For HCoV-229E, 1.5 × 105 stable LY6E-expressing or control cells were seeded in a 12-well plate and infected with HCoV-229E in a serial dilution. Cells were incubated for 2 h at 33 °C, then viral supernatant was removed and an overlay of 1:1 Avicel (2.4%) (Avicel RC-581NF) and 2× Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS) and 100 IU ml−1 penicillin (Gibco)/100 μg ml−1 streptomycin (Gibco) (penicillin-streptomycin) was added. Cells were incubated for 3 d at 33 °C before medium was removed. Cells were washed and stained with crystal violet (Sigma–Aldrich), and p.f.u. values were calculated.

For HCoV-OC43, 5.0 × 104 stable LY6E-expressing or control cells were seeded in a 24-well plate and infected at 33 °C for 1 h with HCoV-OC43 ((multiplicity of infection (MOI) = 1). The virus was aspirated and 10% FBS/1× non-essential amino acids/1× penicillin-streptomycin/RPMI (cRPMI) was added back to the cells. At 24 h post-infection, cells were dissociated using Accumax (Sigma–Aldrich), fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde (PFA), permeabilized per the manufacturer’s protocol (BD Cytofix/Cytoperm), and stained for nucleoprotein (1:500) and a goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (1:2,000). Infection was analysed by flow cytometry.

For MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, 1 × 104 stable LY6E-expressing or control cells were seeded in a 96-well plate and infected at 37 °C in a serial dilution assay. At 3–4 d post-infection, the supernatant was removed and cells were stained with crystal violet (Sigma–Aldrich). The cytopathic effect was determined upon visual inspection, and the median tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) per ml was calculated according to the Reed–Muench method.

For SARS-CoV-2 infection in Huh7.5 cells, 5 × 104 stable LY6E-expressing or control cells were seeded in a 24-well plate and infected at 37 °C for 1 h. At 24 h post-infection, cells were harvested, permeabilized and analysed as described for HCoV-OC43, with the exception of 4% PFA for fixation, and staining for double-stranded RNA (dsRNA; 1:10,000) and a goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1,000).

For MHV-Gluc, 1 × 105 stable LY6E-expressing or control cells were seeded in a 24-well plate and infected with MHV-Gluc (MOI = 0.1) at 37 °C. After 2 h, virus inoculum was removed, cells were washed with PBS and cRPMI was added back. At 24 h post-infection, the cell culture supernatant was harvested, and Gluc activity was measured using a Pierce Gaussia Luciferase Glow Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and a plate luminometer (EnSpire 2300 Multilabel reader; Perkin Elmer). For testing of the virus panel against LY6E, 1 × 104 stable LY6E-expressing or control Huh7.5 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate. Cells were infected with the following viruses and harvested after the indicated times: HCoV-229E (MOI = 0.001; 72 h), HCV-Ypet (MOI = 1; 72 h), CHIKV-GFP (MOI = 0.005; 24 h), hPIV-3-GFP (MOI = 0.015; 24 h), RSV-GFP (MOI = 1.5; 24 h), SINV-GFP (MOI = 0.1; 24 h), VEEV-GFP (MOI = 0.0075; 24 h), WNV-GFP (MOI = 1.5; 24 h), Zika virus (ZIKV) PRVABC59 (MOI = 0.01; 48 h), yellow fever virus 17D-venus (MOI = 0.01; 48 h) and DENV-GFP (MOI = 0.05; 72 h). At the indicated time points, cells were fixed with 4% PFA/PBS. ZIKV-infected cells were stained for viral E protein (1:500) and an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:1,000). Images were acquired with a fluorescence microscope and analysed using ImageXpress Micro XLS (Molecular Devices).

SARS-CoV-2 infection of ACE2-expressing cells

Approximately 3 × 104 Huh7.5 cells were plated in eight-well chamber slides. Cells were infected in a low volume with 0.5 MOI SARS-CoV-2 for 1 h at 37 °C, incubated for 9 h more at full volume and then fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde. Cells were permeabilized, stained for dsRNA (1:500; see the Supplementary Information ‘Antibodies for immunofluorescence and flow cytometry’ section) and imaged as previously described, except mounting was performed with Vectashield with 4′,6-diamidine-2′-phenylindole (DAPI; H-1200; Vector Labs)31. Seven images were acquired for each condition. Images were processed using ImageJ by equally adjusting the minimum brightness to normalize the background and measuring the mean intensity of the entire dsRNA image. Nuclei were enumerated using ImageJ, using the threshold, watershed and analyze particles features. The mean fluorescence intensity per nucleus was determined by dividing the mean intensity of the GFP channel by the total number of nuclei in the field.

HCoV-229E-Rluc infection assay of knockout cells

For infection assays, 1 × 105 target cells were seeded in a 24-well plate 1 d before infection. Cells were infected with HCoV-229E-Rluc (MOI = 0.1) in OptiMEM (Gibco) for 2 h at 33 °C. Cells were washed 1× with PBS, and 10% FBS/1× non-essential amino acids/1× penicillin-streptomycin/DMEM (cDMEM) was added back. Cells were incubated at 33 °C for 24 h, then washed with PBS and lysed using the Renilla Luciferase Assay System kit (Promega). Renilla luciferase (Rluc) activity was measured using a plate luminometer (EnSpire 2300 Multilabel reader; Perkin Elmer). For the reconstitution with CRISPR-resistant LY6E, 2.5 × 104 cells were seeded in a 24-well plate. At 1 d post-seeding, cells were either left untransduced or transduced with a lentiviral vector encoding for CRISPR-resistant LY6E or the empty control. At 48 h post-transduction, cell lysates were either infected with HCoV-229E-Rluc (MOI = 0.1) for 24 h as described above or harvested for western blot.

VSV pseudoparticles

Pseudotyping of VSV*ΔG(Fluc) was performed as previously described32. Briefly, 6 × 105 293LTV cells were seeded in a six-well plate and transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), which was complexed with DNA plasmids driving the expression of either VSV-G protein (positive control), the respective CoV spike proteins or the fluorophore mCherry (negative control). Expression vectors for VSV (serotype Indiana) glycoprotein (VSV-G; GenBank accession number NC_001560), HCoV-229E S (pCAGGS-229E S; GenBank accession number X16816), MERS-CoV S (pCAGGS-MERS S; GenBank accession number JX869059, with a silent point mutation (C4035A, removing internal XhoI)) and SARS-CoV S (pCAGGS-SARS S; GenBank accession number: AY291315.1, with two silent mutations (T2568G and T3327C)) have been described previously33,34. The expression plasmid for SARS-CoV-2 was generated as follows. The coding sequence of a synthetic, codon-optimized (for human cells) SARS-CoV-2 DNA (GeneArt Gene Synthesis; Thermo Fisher Scientific) based on the publicly available protein sequence in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database (NCBI reference sequence YP_009724390.1) was PCR amplified and cloned into the pCG1 expression vector between the BamHI and XbaI restriction sites. The MERS-CoV spike cleavage mutants have been described before20. pCAGGS_mCherry was generated upon cloning of the mCherry reporter gene into the pCAGGS expression vector (the primer sequences and cloning procedure are available upon request). At 20 h post-transfection, cells were infected with VSV-G-trans-complemented VSV*ΔG(FLuc) (MOI = 5) for 30 min at 37 °C, washed with PBS and further incubated for 1 h in cDMEM that was supplemented with monoclonal antibody I1 (ATCC, 1:100)—a neutralizing monoclonal antibody directed to the VSV-G protein. Cells were then washed and cDMEM was added back. Viral supernatant was harvested at 16–24 h post-infection. Cellular debris were removed by centrifugation (3,000g for 10 min) and used to inoculate 2 × 104 target cells in a 96-well plate (six technical replicates). Cells were incubated for 16–18 h at 37 °C before Fluc activity in cell lysates was detected using a plate luminometer (EnSpire 2300 Multilabel reader; Perkin Elmer) and the Bright-Glo Luciferase Assays System (Promega). Experiments with pseudotyped SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 were performed as previously described20.

Cell–cell fusion assay

The cell–cell luciferase/GFP fusion assay has been described before, with slight modifications35. Briefly, 6 × 105 293LTV cells were transfected with plasmids encoding CoV spike proteins (for the constructs, please refer to VSV pseudoparticles; pCAGGS-HCoV-229E, pCAGGS-MERS-CoV, pCAGGS-SARS-CoV and pCAGGS-SARS-CoV-2) together with a split-luciferase/split-GFP construct (Rluc8155-156; DSP1-7). The empty expression plasmid (pCAGGS-mCherry), as well as a construct encoding for VSV-G, served as the negative and positive control, respectively. Some 2 × 105 stable LY6E-expressing or empty control Huh7 or VeroE6 cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with a plasmid encoding the complementary fragment of the split-luciferase/split-GFP protein (Rluc8155-156; DSP8-11). Approximately 30 h post-transfection, both cell populations were dissociated (TrypLE Express; Gibco) and counted, and equal cell numbers (2 × 104 cells each) were co-cultured for 16–20 h at 37 °C. Cells were rinsed with PBS and fixed using 4% PFA in PBS. Four images were acquired using an EVOS FL Auto 2 imaging system equipped with a 4× air objective (NA = 0.13) and stitched using the integrated software (ImageJ 2.0.0-rc-69/1.52p; Java 1.8.0_172 (64 bits); Windows 10, 10.0). Images were processed by applying background subtraction (rolling ball; size = 25 pixels) and measuring the mean intensity of the entire image.

Syncytia formation assay

Cells expressing LY6E or empty control were infected with VSV*ΔG(MERS S) or VSV*ΔG(229E S) at an MOI of 0.01. At 20 h post-infection, the cells were fixed with 3% PFA/PBS and the nuclei were stained with DAPI (Sigma–Aldrich; 1:10,000). An inverted fluorescence microscope (Zeiss) was used to determine the percentage area covered by syncytia.

For the heterologous cell–cell fusion assay, BHK-21 cells were infected with VSV*ΔG(CoV S) at an MOI of 1. After 2 h, the cells were treated with trypsin/EDTA (Life Technologies) and resuspended in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS (2 × 104 cells per ml). The infected BHK-21 cell suspension (500 µl) was seeded into 24-well cell culture plates along with LY6E- or empty control-expressing Huh7 (1 × 104 cells). Cell co-cultures were incubated for 7 h at 37 °C, fixed with 3.6% formaldehyde diluted in PBS (Grogg Chemie) and stained with DAPI. The percentage area covered by syncytia was calculated as above.

Mice

Ly6etm1a embryonic stem cells were obtained from the EUCOMM consortium36 and microinjected into C57BL/6J blastocysts by the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (UTSW) Transgenic Technology Center. Chimeric mice with germline transmission were bred to obtain Ly6etm1a/+ offspring. Ly6etm1a/+ mice were crossed with FLPe-expressing mice (B6N.129S4-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(FLP1)Dym/J; 16226; The Jackson Laboratory) to obtain Ly6efl/+ offspring, which were bred to homozygosity. Conditional Ly6efl/fl mice were bred to Vav1-iCre transgenic mice (B6.Cg-Commd10Tg(Vav1-icre)A2Kio/J; 008610; The Jackson Laboratory) to obtain Ly6eΔHSC/+ (Ly6efl/+; Vav1-iCre) offspring. Ly6eΔHSC/+ mice were bred to obtain Ly6eΔHSC (Ly6efl/fl; Vav1-iCre) offspring, which harbour a deletion of exon 3 and 4 in HSCs. Experimental animals were obtained by crossing Ly6eΔHSC and Ly6efl/fl mice. Littermates were used for the majority of experiments when possible; otherwise, mice of a similar age (within 2 weeks) were used. Sample size was chosen based on published studies, and no randomization or blinding was performed aside from the scoring of liver histology. Genotype was confirmed by PCR of genomic DNA in house or outsourced to Transnetyx. Ablation of Ly6e was confirmed by quantitative PCR in immune cells from the spleen, liver or bone marrow. Ifnar−/− mice on a C57BL/6J background were a kind gift from N. Yan (UTSW). Animal studies were carried out in specific pathogen-free barrier facilities managed and maintained by the UTSW Animal Resource Center. Facilities were maintained at an acceptable range of 68–79 °F at a humidity of 30–70% on a 12 h dark/12 h light cycle. All procedures used in this study complied with federal and institutional guidelines enforced by the UTSW Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were granted institutional approval after veterinary and committee review.

In vivo infection, viral titres, liver ALT and liver histology

Female and male mice (6–12 weeks old) were injected intraperitoneally with MHV-A59 diluted in PBS to the indicated titres, or PBS for a mock infection control. Unless otherwise indicated, Ly6efl/fl mice were used for mock infection controls. All infected mice were monitored daily for weight and mortality. Animals that lost more than 20% of their original body weight were euthanized per Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Viral titres in liver and spleen were determined from frozen organs after weighing, homogenization and plaque assay on L929 cells. ALT was measured in fresh, unfrozen serum using VITROS MicroSlide Technology by the UTSW Mouse Metabolic Core. Livers were fixed in 10% neutral buffer formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 µM and stained with haematoxylin and eosin. Slides were analysed by an independent pathologist (UTSW Animal Resource Center) who was blinded to the experimental conditions. A numerical score was assigned for the degree of inflammation and degree of necrosis for each liver. Inflammatory cell infiltration was scored using the following criteria: 0 = none, 1 = minimal, 2 = mild, 3 = moderate and 4 = marked. The necrosis score was defined by the percentage of necrosis (0 = none, 1 = <2%, 2 = 2–20%, 3 = 21–40% and 4 = >40%).

Primary cell preparation for flow cytometry

Primary cells were isolated from female and male mice (6–15 weeks old). All primary cells were maintained in 10% FBS/10 mM HEPES/1 mM sodium pyruvate/2 mM l-glutamine/1× penicillin-streptomycin/RPMI (cRPMI2) unless otherwise indicated.

Primary BMDMs were prepared as described previously37. Viable cells were quantified using trypan blue exclusion. BMDMs were plated at 2.5 × 104 cells per well in non-treated 24-well tissue culture plates. Cells were infected the next day with MHV-A59-GFP (MOI = 0.1) and isolated 6 h post-infection for analysis by flow cytometry.

Splenocytes were prepared by mashing whole spleens against a 70-µM cell strainer. Red blood cells were removed using RBC lysis buffer (Tonbo Biosciences). Viable cells were quantified using trypan blue exclusion. For in vitro infection, splenocytes were plated at 1 × 106 cells per well in non-treated six-well tissue culture plates and immediately infected with MHV-A59-GFP (MOI = 1) for 2 h before increasing the media volume fivefold. Infected cells were isolated 8 h post-infection, stained with a fluorescent viability dye (Ghost Dye Violet 450; 1:1,000; Tonbo Biosciences) and fixed in 1% PFA/PBS. The next day, fixed cells were treated with anti-CD16/CD32 (1:100; Tonbo Biosciences), then stained with antibodies that recognize surface lineage markers and analysed by flow cytometry.

Livers were perfused by PBS injection into the inferior vena cava and out of the portal vein. Blanched livers were minced with sterile scissors and mashed against a 70-µM cell strainer. Hepatocytes and large debris were pelleted at 60g for 1 min, at 22 °C, with no brake. Supernatants containing intrahepatic immune cell (IHICs) and residual hepatocytes were pelleted at 480g for 8 min, at 22 °C, with maximum brake, and resuspended in 37.5% Percoll (Sigma–Aldrich)/cRPMI2. The remaining hepatocytes were separated from the IHICs by centrifugation at 850g for 30 min, at 22 °C, with no brake. Red blood cells were removed from the resulting pellet with RBC lysis buffer (Tonbo Biosciences). Viable cells were quantified using trypan blue exclusion. IHICs and splenocytes (4 × 105) from infected or mock-infected mice were stained with a fluorescent viability dye (Ghost Dye Violet 450; 1:1,000; Tonbo Biosciences), treated with anti-CD16/CD32 (1:100; Tonbo Biosciences), stained with antibodies that recognize surface lineage markers and then fixed in 1% PFA/PBS. Fixed volumes of cell suspensions were analysed by flow cytometry the next day. Absolute cell counts were determined by multiplying the final number of lineage marker-positive cells by the dilution factor used to normalize the cell counts for antibody staining.

All primary cell samples were resuspended in 3% FBS/PBS, analysed using an S1000 Flow Cytometer with an A600 96-well plate high-throughput extension and compensated using CellCapTure software (Stratedigm). Data were analysed with FlowJo Software (Tree Star). The flow gating strategy for liver and spleen immune cells is included in Extended Data Fig. 9.

Statistical analysis

Differences in data were tested for significance using GraphPad Prism version 8.3.1 for Windows (GraphPad). For details regarding the statistical tests applied, please refer to the figure captions. P values < 0.05 were considered significant. P values > 0.05 are listed by figure in Supplementary Table 4.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files, or are available on request. The RNA-seq data discussed in this publication have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (GSE146074). The data used for scRNA-seq analysis of hAECs have been reported previously38. The data used for RNA-seq analysis of LY6E induction in hAECs after viral infection have been reported previously39. The GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) accession codes for the viral gene sequences used to generate the spike protein pseudoparticles are: NC_001560 (VSV-G); X16816 (HCoV-229E S); JX869059 (MERS-CoV S); and AY291315.1 (SARS-CoV S). The NCBI Reference Sequence for SARS-CoV-2 is available via the accession code YP_009724390.1. The NCBI accession number for generating the expression plasmid for Camelus dromedarius LY6E is XM_031439745.1. Source data are provided with this paper.

Change history

07 August 2020

In the version of this Letter originally published, Hans-Heinrich Hoffmann’s first name was formatted as an initial. This has now been corrected and their full name is displayed.

References

Zhu, N. et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 727–733 (2020).

Drosten, C. et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 1967–1976 (2003).

Zaki, A. M., van Boheemen, S., Bestebroer, T. M., Osterhaus, A. D. & Fouchier, R. A. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N. Engl. J. Med. 367, 1814–1820 (2012).

Kindler, E., Thiel, V. & Weber, F. Interaction of SARS and MERS coronaviruses with the antiviral interferon response. Adv. Virus Res. 96, 219–243 (2016).

Corman, V. M., Muth, D., Niemeyer, D. & Drosten, C. Hosts and sources of endemic human coronaviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 100, 163–188 (2018).

Wang, B. X. & Fish, E. N. Global virus outbreaks: interferons as 1st responders. Semin. Immunol. 43, 101300 (2019).

Cervantes-Barragan, L. et al. Control of coronavirus infection through plasmacytoid dendritic-cell-derived type I interferon. Blood 109, 1131–1137 (2007).

Schoggins, J. W. Interferon-stimulated genes. What do they all do? Annu. Rev. Virol. 6, 567–584 (2019).

Schoggins, J. W. et al. A diverse range of gene products are effectors of the type I interferon antiviral response. Nature 472, 481–485 (2011).

Dittmann, M. et al. A serpin shapes the extracellular environment to prevent influenza A virus maturation. Cell 160, 631–643 (2015).

Mar, K. B. et al. LY6E mediates an evolutionarily conserved enhancement of virus infection by targeting a late entry step. Nat. Commun. 9, 3603 (2018).

Hackett, B. A. & Cherry, S. Flavivirus internalization is regulated by a size-dependent endocytic pathway. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 4246–4251 (2018).

Yu, J., Liang, C. & Liu, S. L. Interferon-inducible LY6E protein promotes HIV-1 infection. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 4674–4685 (2017).

Yu, J., Liang, C. & Liu, S. L. CD4-dependent modulation of HIV-1 entry by LY6E. J. Virol. 93, e01866-18 (2019).

Upadhyay, G. Emerging role of lymphocyte antigen-6 family of genes in cancer and immune cells. Front. Immunol. 10, 819 (2019).

Hoffmann, M., Kleine-Weber, H. & Pohlmann, S. A multibasic cleavage site in the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 is essential for infection of human lung cells. Mol. Cell 78, 779–784 (2020).

Xia, S. et al. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 (previously 2019-nCoV) infection by a highly potent pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitor targeting its spike protein that harbors a high capacity to mediate membrane fusion. Cell Res. 30, 343–355 (2020).

Heald-Sargent, T. & Gallagher, T. Ready, set, fuse! The coronavirus spike protein and acquisition of fusion competence. Viruses 4, 557–580 (2012).

Park, J. E. et al. Proteolytic processing of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus spikes expands virus tropism. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 12262–12267 (2016).

Kleine-Weber, H., Elzayat, M. T., Hoffmann, M. & Pohlmann, S. Functional analysis of potential cleavage sites in the MERS-coronavirus spike protein. Sci. Rep. 8, 16597 (2018).

Langford, M. B., Outhwaite, J. E., Hughes, M., Natale, D. R. C. & Simmons, D. G. Deletion of the Syncytin A receptor Ly6e impairs syncytiotrophoblast fusion and placental morphogenesis causing embryonic lethality in mice. Sci. Rep. 8, 3961 (2018).

Matthews, A. E. et al. Antibody is required for clearance of infectious murine hepatitis virus A59 from the central nervous system, but not the liver. J. Immunol. 167, 5254–5263 (2001).

Phares, T. W. et al. CD4 T cells promote CD8 T cell immunity at the priming and effector site during viral encephalitis. J. Virol. 86, 2416–2427 (2012).

Wijburg, O. L., Heemskerk, M. H., Sanders, A., Boog, C. J. & Van Rooijen, N. Role of virus-specific CD4+ cytotoxic T cells in recovery from mouse hepatitis virus infection. Immunology 87, 34–41 (1996).

Wijburg, O. L., Heemskerk, M. H., Boog, C. J. & Van Rooijen, N. Role of spleen macrophages in innate and acquired immune responses against mouse hepatitis virus strain A59. Immunology 92, 252–258 (1997).

Cervantes-Barragan, L. et al. Type I IFN-mediated protection of macrophages and dendritic cells secures control of murine coronavirus infection. J. Immunol. 182, 1099–1106 (2009).

Weiss, S. R. & Leibowitz, J. L. Coronavirus pathogenesis. Adv. Virus Res. 81, 85–164 (2011).

Eriksson, K. K., Cervantes-Barragan, L., Ludewig, B. & Thiel, V. Mouse hepatitis virus liver pathology is dependent on ADP-ribose-1′′-phosphatase, a viral function conserved in the alpha-like supergroup. J. Virol. 82, 12325–12334 (2008).

Karnam, G. et al. CD200 receptor controls sex-specific TLR7 responses to viral infection. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002710 (2012).

Lalezari, J. P. et al. Enfuvirtide, an HIV-1 fusion inhibitor, for drug-resistant HIV infection in North and South America. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 2175–2185 (2003).

Richardson, R. B. et al. A CRISPR screen identifies IFI6 as an ER-resident interferon effector that blocks flavivirus replication. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 1214–1223 (2018).

Torriani, G. et al. Identification of clotrimazole derivatives as specific inhibitors of arenavirus fusion. J. Virol. 93, e01744-18 (2019).

Gierer, S. et al. The spike protein of the emerging betacoronavirus EMC uses a novel coronavirus receptor for entry, can be activated by TMPRSS2, and is targeted by neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 87, 5502–5511 (2013).

Hoffmann, M. et al. Differential sensitivity of bat cells to infection by enveloped RNA viruses: coronaviruses, paramyxoviruses, filoviruses, and influenza viruses. PLoS ONE 8, e72942 (2013).

Qing, E., Hantak, M., Perlman, S. & Gallagher, T. Distinct roles for sialoside and protein receptors in coronavirus infection. mBio 11, e02764-19 (2020).

Skarnes, W. C. et al. A conditional knockout resource for the genome-wide study of mouse gene function. Nature 474, 337–342 (2011).

Agac, D., Estrada, L. D., Maples, R., Hooper, L. V. & Farrar, J. D. The β2-adrenergic receptor controls inflammation by driving rapid IL-10 secretion. Brain Behav. Immun. 74, 176–185 (2018).

Kelly, J. N. et al. Comprehensive single cell analysis of pandemic influenza A virus infection in the human airways uncovers cell-type specific host transcriptional signatures relevant for disease progression and pathogenesis. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.03.014282 (2020).

V’kovski, P. et al. Disparate temperature-dependent virus–host dynamics for SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV in the human respiratory epithelium. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.27.062315 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank the sequencing facility in Bern, the diagnostic facility of the Institute of Virology and Immunology (IVI) and the Animal Resource Center at UTSW for generously contributing reagents and infrastructure, which greatly enhanced this study. Furthermore, we are grateful to R. Pohorelsky, S. Elias and N. Garcia from the UTSW Animal Resource Center for assisting with the in vivo experiments. We are grateful to S. Locher (IVI, Bern, Switzerland) for cloning the MERS spike complementary DNA. Furthermore, we thank B. J. Bosch, M. Müller and C. Drosten for reagents and the SARS-CoV-2 virus stocks. We thank the following investigators for contributing viral molecular clones or viral stocks: P. L. Collins (respiratory syncytial virus and human parainfluenza virus type 3), I. Frolov (Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus), M. T. Heise (Sindbis virus), S. Higgs (Chikungunya virus) and the CDC (ZIKV). Finally, we thank all members (past and present) of the IVI, the Schoggins laboratory and the Rice laboratory for useful discussions. S. Pfaender was supported by the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement 748627 and the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF; grant no. 310030 173085). K.B.M. and J.W.S. were supported in part by The Clayton Foundation and The American Lung Association. J.W.S. was additionally supported by NIH grant no. AI117922 and a Burroughs Wellcome Fund ‘Investigators in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease’ award. K.B.M. was additionally supported by NIH Training Grant no. AI005284. S. Pöhlmann was supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), the RAPID Consortium and grant no. 01KI1723D. N.W.H. was supported by NIH grant no. AI132751. E.M., H.H.H., M.S. and C.M.R. were supported in part by NIH grant nos. AI091707 and AI091707-10S1 and The G. Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation. R.D. was supported by the SNF (grant no. 179260). G.Z. was supported by SNF grant no. 166265. P.V. and J.N.K. were supported by the SNF (grant nos. 310030_173085 (P.V. and J.N.K.) and CRSII3_160780 (J.N.K.)). A.K. was supported by the BMBF (grant RAPID; 01KI1723A). V.T. was supported by the SNF (grant nos. 310030_173085 and CRSII3_160780) and BMBF (grant RAPID; 01KI1723A). I.N.B. and M.B.M. were supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under grant nos. 2016217834 and 2019274212, respectively.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. Pfaender, K.B.M., E.M., C.M.R., J.W.S. and V.T. designed the project. S. Pfaender, K.B.M., E.M., A.K., I.N.B., P.V., W.F., D.H., N.E., H.S., H.K.-W., M.H., H.-H.H., M.S., M.B.M. and G.Z. performed and analysed the in vitro experiments. K.B.M. performed and analysed the in vivo experiments with assistance from W.F. and N.W.H. M.W.-C. performed the histological analysis. D.T. performed the statistical analysis and analysis of the MHV RNA-seq dataset. J.N.K. performed the statistical analysis and analysis of the hAEC RNA-seq dataset. R.D., S. Pöhlmann, E.S. nd T.G. contributed to the design and implementation of the research. S. Pfaender, K.B.M. and J.W.S. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to editing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 The antiviral activity of LY6E is conserved, independent of CoV receptors, and extends to HCV.

a, Duplicate screens depicting HCoV-229E infection (48 hours post-infection) in Huh7 cells expressing ISGs. b, SARS-CoV-2 infection of Huh7.5 cells expressing LY6E or a control (FLuc). c, HCoV-229E infection of Huh7.5 cells expressing vector control or human (H. sapiens), camel (C. dromedarius), bat (P. alecto), mouse (M. musculus), or rhesus (M. mulatta) LY6E orthologues. d, Stable LY6E or empty vector expressing Huh7.5 cells infected with MERS-CoV. e–g, UMAP visualization of CD13 (e) DPP4 (f), and ACE2 (g) expression and distribution among distinct cell types in hAEC cultures from 2 donors by scRNA-seq. h, SARS-CoV-2 infection of LY6E or control vector (FLuc) Huh7.5 cells co-expressing control vector (empty). Blue: DAPI, green: SARS-CoV-2 dsRNA, red: TagRFP encoded in SCRPSY-ACE2 vector. i, Western blot of Huh7.5 expressing LY6E or FLuc and empty vector or ACE2. j, k, Stable LY6E or empty vector expressing Huh7 cells were assessed for cell surface expression of CD13 (j) and DPP4 (k). l, Stable Huh7.5 cells expressing either LY6E or empty vector infected with HCoV-229E, HCV, CHIKV, hPIV-3, RSV, SINV, VEEV, WNV, ZIKV, YFV, and DENV. m, HCoV-229E-Rluc infection of naïve or stably transduced Huh7 cells expressing empty vector control or LY6/uPAR family members. n, HCoV-229E-Rluc infection of Huh7 cells expressing control vector (FLuc), LY6E WT, LY6E HA or specific block mutants9. In h, scale bars are 100 µM. Immunofluorescence and western blot images are depicted exemplarily from n=3 (h) and n=3 (i). Data depicts mean of independent biological replicates, n=3 (b–d, j–n). Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed unpaired student’s t-test with Welch’s correction (b, j, k), ordinary one-way ANOVA with Dunnett`s correction for multiple comparison (c, d, m, n), two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (l). Error bars: SD (b–d, j–n). P values (left-to-right): b, ** p=0.0098; c, **** p=<0.0001, ** p=0.0030; d, * p=0.0118, ** p=0.0013; l, **** p=>0.0001, ** p=0.0095; m, **** p=<0.0001; n, **** p=<0.0001, <0.0001, *** p=0.0005, **** p=<0.0001, *** p=0.0003, **** p=<0.0001, <0.0001, <0.0001, *** p=0.0001, **** p=<0.0001.

Extended Data Fig. 2 LY6E does not affect CoV binding, replication, translation, assembly, or release.

a, Stable LY6E expressing or empty control Huh7 cells were incubated with HCoV-229E and binding analyzed immediately (t=0 h) or after incubation for 24 hours (t=24 h) by RT-qPCR. b–f, Stable LY6E expressing or control Huh7 cells were mock-infected or infected with HCoV-229E-Rluc. Cell lysates were harvested at the indicated time points and intracellular viral RNA was extracted, and viral replication detected via qRT-PCR (b). Cell supernatant was harvested, extracellular viral RNA was extracted, and viral replication detected via qRT-PCR (c). Cell lysates were harvested, and intracellular Renilla luciferase activity was detected upon cell lysis (d). Cells were subjected to 3 rounds of freeze/thaw cycles. Cell debris was removed, and the supernatant titrated on naïve Huh7 cells. Intracellular infectivity was determined (e). Supernatant was harvested and titrated on naïve Huh7 cells to determine extracellular infectivity (f). Data represent mean of independent biological replicates, n=3 (a–f). Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (a). Error bars: SD (a–f).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Generation of recombinant VSV vector driving CoV S protein expression (VSV*∆G(CoV)) and heterologous cell-cell fusion assay.

a, Schematic depiction of the generation of recombinant VSV*∆G(CoV S) expressing both CoV S protein and GFP reporter protein. The respective CoV S genes were inserted into the genomic VSV*∆G cDNA and recombinant virus was generated in BHK-G43 cells expressing the VSV G protein. The recombinant virus produced in this way harbored the VSV G protein in the envelope allowing CoV S protein-independent infection of cells. Infection of cells with VSV*∆G(CoV S) led to the expression of CoV S protein and consequent syncytia formation. b, Heterologous syncytia formation assay. BHK-21 cells were infected with VSV G protein trans-complemented VSV*∆G(CoV S) viruses or were mock-infected, followed by co-culture with LY6E or empty control Huh7 cells. Syncytia formation was determined. Blue: DAPI, green: GFP, red: TagRFP encoded in SCRPSY vector. c, Quantification of VSV*∆G(CoV S) induced syncytia depicted as percentage syncytia area. Three independent areas were analyzed per biological replicate (circle, square, triangle). Data represent mean of independent biological replicates, n=3 (c). In b, scale bar is 20 µM. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (c). Error bars: SD. P values: c (left-to-right), **** p=6.0 x 10-9, **** p=1.1 x 10-15.

Extended Data Fig. 4 The antiviral effect of LY6E is independent of proteolytic cleavage of CoV spike protein.

a, Schematic depiction of cell entry routes of CoVs and intervention by selected compounds. b, c, LY6E or empty control-expressing Huh7 cells naïve for (b) or ectopically overexpressing TMPRSS2 (c) were pre-treated with the indicated compounds before infection with HCoV-229E-Rluc. d, Schematic depiction of the CoV spike (S) protein containing the subunits S1 and S2. Arrows indicate the S1/S2’ cleavage site, a proposed cleavage site for cathepsin L (CTSL’) and the S2’ cleavage site. Amino acid exchanges disrupting the respective cleavage sites are depicted in red. e, Western blot of S cleavage in LY6E or empty control-expressing Huh7 cells transfected with a plasmid encoding for MERS-CoV S protein (S0= uncleaved, S2= S2 subunit). f, MERS CoV S cleavage was analyzed by quantification of S0 and S2 bands. g, LY6E or empty control-expressing Huh7 cells inoculated with CoV-pseudoparticles (pp) harboring MERS-CoV S WT or MERS-CoV S proteins containing various cleavage site mutations. Data represent mean of independent biological replicates, n=3 (b), n=3 (c), n=3 (e), n=3 (f), n=5 (g). Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons (b, c, g) or two-tailed unpaired student’s t-test with Welch’s correction (f). Error bars: SD. P values (left-to-right): b, **** p=4.4 x 10-9, p=1.6 x 10-9, p=6.2 x 10-9, p=7.5 x 10-10, p=3.0 x 10-10, * p=0.0179; c, *** p=0.0007, p=0.0005, p=0.0006, **** p=4.8 x 10-8, p=1.8 x 10-8.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Generation of hematopoietic Ly6e conditional knockout mouse.

a, Strategy used to generate Ly6eΔHSC mice. Hematopoietic-tissue specific ablation of Ly6e was achieved by crossing Ly6efl/fl mice with transgenic Vav1-iCre mice to remove the LoxP-flanked exon III and IV, resulting in a 17 amino acid truncated variant of the 130 amino acid full-length protein. Primers used for tissue genotyping and gene expression are also depicted as arrows. b, Gel electrophoresis of tissue genotyping PCR, representing Ly6efl/fl, Ly6efl/+, and Ly6e+/+ mice. c, Ly6e gene expression in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM). d, Infection of BMDM. For c-d, n=9 (Ly6efl/fl) or n=8 (Ly6eΔHSC) mice from three pooled experiments. The gel shown in b is representative of all genotyping performed to identify Ly6efl/fl mice. Data for c, d is shown normalized to Ly6efl/fl values. Statistical significance was determined by using two-tailed unpaired student’s t-test with Welch’s correction (c) or two-tailed ratio-paired t-test (d). Data are presented as mean values ± SD (c-d). P values: c, *** p=0.0010. d, ** p=0.0021.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Ly6eΔHSC mice are susceptible to mouse hepatitis virus.

a, b, Male Ly6efl/fl and Ly6eΔHSC mice injected with PBS or MHV and monitored for survival (a) and weight loss (b). c–n, Mice were euthanized at 3- (c–h) or 5- (i–n) days post-infection for determination of serum ALT (c,i), viral titers in liver (d,j) and spleen (e,k), and liver necrosis and inflammation (f–h, l–n). For a, b, n=15 for days 0-6, n=14 for days 6-14, (Ly6efl/fl), n=10 for days 0-5, n=4 for days 5-6, n=0 for days 6-14 (Ly6eΔHSC) from three pooled experiments. For c–g, n=8 (Ly6efl/fl,), n=6 (Ly6eΔHSC), or n=6 (PBS) from two pooled experiments; images shown in h are representative of the same cohorts. For i–m, n=8 (Ly6efl/fl,), n=6 (Ly6eΔHSC), or n=3 (PBS) from two pooled experiments; images shown in n are representative of the same cohorts. In h, n, scale bars are 500 µM (4x) and 100 µM (20x). Significance for was tested by two-sided Mantel-Cox test (a), two-tailed unpaired student’s t-test with Welch’s correction (c–e, i–k), two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test (f, g, l, m). Data are presented as mean values ± SEM (b) or SD (c–g, i–m). P value: a, **** p=3.946 x 10-6; e, ** p=0.0026; k, * p=0.0119.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Ly6eΔHSC mice have enhanced sensitivity to mouse hepatitis virus and a differential gene expression profile.

a–j, Female (a–e) and male (f, g) Ly6efl/fl and Ly6eΔHSC mice injected with PBS or MHV and assessed for serum ALT (a, f), viral titers in liver (b, g) and spleen (c, h), and liver necrosis and inflammation (d, e, i, j). k–n, Female Ly6efl/fl and Ly6eΔHSC mice injected with PBS or MHV and whole livers were imaged. Mock-infected (PBS) Ly6eΔHSC mice (k), mock-infected Ly6efl/fl mice (l), MHV-infected Ly6eΔHSC mice (m), MHV-infected Ly6efl/fl mice (n). o, p, Representative genes from transcriptomic analysis of liver (o) and spleen (p) from MHV-infected and PBS-injected female Ly6efl/fl and Ly6eΔHSC mice. For a–e, n=8 (Ly6efl/fl,), n=8 (Ly6eΔHSC), or n=3 (PBS) from two pooled experiments per sex. For f–j, n=9 (Ly6efl/fl,), n=7 (Ly6eΔHSC), or n=3 (PBS) two pooled experiments. For k–p, n=3. Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed unpaired student’s t-test with Welch’s correction (a–c, f–h), two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test (d, e, i, j). Data are presented as mean values ± SD (a–j; o, p). P value: a, * p=0.0234; b, * p=0.0428; c, *** p=0.0004; d, * p=0.0210; e, ** p=0.0054.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Dynamic transcriptional changes in liver and spleen of Ly6eΔHSC vs Ly6efl/fl mice.

Depicted are fold changes in liver and spleen gene expression from Ly6eΔHSC mice compared to Ly6efl/fl mice. RPKM values from RNA-seq data for liver (a) and spleen (b) were used to calculate fold changes. Crossed out genes were not detected in either KO or WT mice at respective conditions.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Gating strategy for intrahepatic and splenic immune cell identification.

Antibody-stained suspensions of isolated intrahepatic immune cells or splenic immune cells were first analyzed by forward scatter/side scatter to remove debris events, then gated for exclusion of a viability dye (Ghost Dye Violet 450), and finally for selection of single cell events. A dump-gate strategy was used to identify immune cell populations as indicated in the diagram. FITC-conjugated fluorophores were used for immunophenotyping experiments and PE-conjugated fluorophores were used for ex vivo infections.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Ly6e protects immune cells from mouse hepatitis virus infection.

a, b, Immune cell counts from liver (a) and spleen (b) of MHV-infected or PBS-injected male mice. c, d, Infection of cultured splenocytes from females (c) and males (d) normalized to average (line at 100) of Ly6efl/fl mice. For a, b, n=8 (infected Ly6efl/fl), n=7 (infected Ly6eΔHSC), n=4 PBS-injected from two pooled experiments. For c, n=9 (Ly6efl/fl and Ly6eΔHSC) and n=8 (Ifnar-/-) from four pooled experiments. For d, n=9 (Ly6efl/fl), n=6 (Ly6eΔHSC), or n=6 (Ifnar-/-) mice from four pooled experiments. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (a–d). For box plots, center line indicates mean and upper and lower bounds respectively indicate maximum and minimum replicate values (a, b). Data are presented as mean values ± SD (a–d). P values (top-bottom, then left-right): a, *** p=0.0008; **** p=5.6844 x 10-7, **** p=3.1123 x 10-6, **** p=2.337 x 10-5, *** p=0.0002; **** p=1.7135 x 10-5, *** p=0.0001, * p=0.0216, ** p =0.0075, * p=0.0494; *** p=0.0002, *** p=0.0002, ns p=0.9999, * p=0.0182; *** p=0.0004, *** p=0.0008, **** p=7.354 x 10-5; ** p=0.0011, * p=0.0421, * p=0.0160, b, * p=0.0215; * p=0.0449; ** p=0.0081, ** p=0.0022, * p=0.0131; ** p=0.0044, * p=0.0299; * p=0.0179, * p=0.0194; *** p=0.0007. c, * p=0.0288; d, * p=0.0104; * p=0.0240.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary methods and Tables 1–4.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Unprocessed western blots for Fig. 1m,o.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Unprocessed western blots for Extended Data Fig 1i. The gel was cut at ~60 kDa and probed/developed independently.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Unprocessed western blot for Extended Data Fig. 4e.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pfaender, S., Mar, K.B., Michailidis, E. et al. LY6E impairs coronavirus fusion and confers immune control of viral disease. Nat Microbiol 5, 1330–1339 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-020-0769-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-020-0769-y

This article is cited by

-

Innovative biomarkers TCN2 and LY6E can significantly inhibit respiratory syncytial virus infection

Journal of Translational Medicine (2024)

-

Interferon-stimulated gene PVRL4 broadly suppresses viral entry by inhibiting viral-cellular membrane fusion

Cell & Bioscience (2024)

-

Innate immune recognition against SARS-CoV-2

Inflammation and Regeneration (2023)

-

PLSCR1 is a cell-autonomous defence factor against SARS-CoV-2 infection

Nature (2023)

-

LY6E is a pan-coronavirus restriction factor in the respiratory tract

Nature Microbiology (2023)