Abstract

The recent spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) exemplifies the critical need for accurate and rapid diagnostic assays to prompt clinical and public health interventions. Currently, several quantitative reverse transcription–PCR (RT–qPCR) assays are being used by clinical, research and public health laboratories. However, it is currently unclear whether results from different tests are comparable. Our goal was to make independent evaluations of primer–probe sets used in four common SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic assays. From our comparisons of RT–qPCR analytical efficiency and sensitivity, we show that all primer–probe sets can be used to detect SARS-CoV-2 at 500 viral RNA copies per reaction. The exception for this is the RdRp-SARSr (Charité) confirmatory primer–probe set which has low sensitivity, probably due to a mismatch to circulating SARS-CoV-2 in the reverse primer. We did not find evidence for background amplification with pre-COVID-19 samples or recent SARS-CoV-2 evolution decreasing sensitivity. Our recommendation for SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic testing is to select an assay with high sensitivity and that is regionally used, to ease comparability between outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was first identified as the cause of an outbreak of pneumonia in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 and rapidly spread around the world1,2,3, exemplifying the critical need for accurate and rapid diagnostic assays to prompt clinical and public health interventions. In response, several molecular assays (that is, quantitative reverse transcription–PCR (RT–qPCR)) were developed to detect COVID-19 cases4,5,6,7; however, it is not clear to many clinical, research and public health laboratories which assay they should adopt or whether the data are comparable. Independent evaluations of the designed primer–probe sets used in primary SARS-CoV-2 RT–qPCR detection assays are necessary to compare findings across studies and select appropriate assays for in-house testing. Our goal was to compare the analytical efficiencies and sensitivities of the primer–probe sets used in four commonly used SARS-CoV-2 RT–qPCR assays developed by the China Center for Disease Control (China CDC)7, United States CDC (US CDC)6, Charité Institute of Virology, Universitätsmedizin Berlin (Charité)5 and Hong Kong University (HKU)4 (Supplementary Table 1). Importantly, we did not directly compare the assays per se, as that would have involved many different variables. Here, we used the same (1) primer–probe concentrations (500 nM of forward and reverse primer and 250 nM of probe); (2) PCR reagents (New England Biolabs, Luna Universal Probe One-step RT–qPCR kit); and (3) thermocycler conditions (10 min at 55 °C, 1 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles (45 for clinical samples) of 10 s at 95 °C and 30 s at 55 °C) in all reactions.

Results

Generation of RNA transcript standards for RT–qPCR validation

A barrier to implemention and validation of RT–qPCR molecular assays for SARS-CoV-2 detection was the availability of virus RNA standards. Using RNA from a SARS-CoV-2 isolate derived from an early COVID-19 case in the United States8, we generated small RNA transcripts (704–1,363 nt) from the non-structural protein 10 (nsp10), RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), non-structural protein 14 (nsp14), envelope (E) and nucleocapsid (N) genes spanning the primer and probe sets of each assay (Extended Data Fig. 1 and Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). By measuring PCR amplification using tenfold serial dilutions of our RNA transcript standards, we found the efficiencies of each of the nine primer–probe sets to be >90% (Extended Data Fig. 1), which match the criteria for an efficient RT–qPCR assay9. Our RNA transcripts can thus be used for assay validation, positive controls and standards to quantify viral loads—critical steps for a diagnostic assay. Our protocol to generate the RNA transcripts is openly available10, and any clinical or research diagnostic laboratory can directly request them for free through our laboratory website (www.grubaughlab.com).

Analytical comparisons of RT–qPCR primer–probe sets

By testing each of the nine primer–probe sets using tenfold dilutions of SARS-CoV-2 RNA derived from cell culture8 (Fig. 1a) or tenfold dilutions of SARS-CoV-2 RNA spiked into RNA extracted from pooled nasopharyngeal swabs taken from patients in 2017 (SARS-CoV-2 RNA-spiked mocks; Fig. 1b), we again found PCR amplification efficiencies to be near or above 90% (Fig. 1c). Our measured PCR efficiencies corresponded to an average of 3.5 cycle threshold (Ct) values between the tenfold SARS-CoV-2 RNA dilutions (that is, slope), with a range of 3.1–3.7 corresponding to the highest and lowest efficiencies, respectively (Fig. 1c; see Source data for Ct values). These again match the criteria for efficient RT–qPCR9. To measure the analytical sensitivity of virus detection, we used the Ct value with which the expected linear dilution series would cross the y-intercept when tested with one viral RNA copy μl–1 of RNA. Our measured sensitivities (y-intercept Ct values) were similar among most of the primer–probe sets, except for the RdRp-SARSr (Charité) set (Fig. 1d). We found that Ct values from the RdRp-SARSr set (using only RdRp_SARSr-P2 (probe 2)) were usually 6–10 Ct higher (lower virus detection) than in the other primer–probe sets.

a,b, Mean Ct values for nine primer–probe sets and a human control primer–probe set targeting the human RNase P gene tested for two technical replicates with tenfold dilutions of full-length SARS-CoV-2 RNA (a) and pre-COVID-19 nasopharyngeal swabs spiked with known concentrations of SARS-CoV-2 RNA (SARS-CoV-2 RNA-spiked mocks (b)). The CDC human RNase P (RP) assay was included as an extraction control. c,d, From the dilution curves in a,b, PCR efficiency (c) and y-intercept Ct values (measured analytical sensitivity) (d) were calculated for each of nine primer–probe sets. Symbols depict sample type: squares represent tests with SARS-CoV-2 RNA and diamonds represent SARS-CoV-2 RNA-spiked mock samples. Colours denote the nine tested primer–probe sets. Dashed lines indicate 90% PCR efficiency (c) and the detection limit (d). The primer and probe sequences can be found in Supplementary Table 1. Data used to make this figure can be found in Source Data Fig. 1.

To determine the lower limit of detection and the occurrence of false-positive or inconclusive detections, we tested the primer–probe sets using SARS-CoV-2 RNA spiked into RNA extracted from pooled nasopharyngeal swabs from patients with respiratory disease during 2017 (pre-COVID-19). We made four independent pools of viral transport medium from four nasopharyngeal swabs, and tested six technical replicates of each without virus (24 total replicates) or two replicates of each with 100, 101 or 102 viral RNA copies μl–1 of extracted nucleic acid concentrations (eight total replicates each). From the pooled nasopharyngeal swabs without viral RNA, we did not detect RT–qPCR amplification for any of the tested primer–probe sets (Fig. 2). These findings suggest that there is no cross-reactivity between the tested primer–probe sets and host or possible other microbial nucleic acid present in nasopharyngeal swabs from non-COVID-19 patients. At 100 and 101 viral RNA copies μl–1, our results show that all primer–probe sets, except RdRp-SARSr and 2019-nCoV_N2, were able to partially detect (Ct < 40) SARS-CoV-2 from clinical sample (Fig. 2). At 102 viral RNA copies μl–1, we could detect viral RNA and differentiate between negative samples for all primer–probe sets except for the RdRp-SARSr (Charité) set, which was negative (Ct > 40) for all 100–102 viral RNA copies μl–1 concentrations (Fig. 2). Our mock clinical samples demonstrated that all primer–probe sets, except RdRp-SARSr (Charité), are 100% sensitive to SARS-CoV-2 detection at 100 viral RNA copies μl–1 of extracted nucleic acid (500 copies per reaction), and 0–50% sensitive at one to ten viral RNA copies μl–1 (5–50 copies per reaction).

The lower detection limit of nine primer–probe sets, as well as the human RNase P control from RNA extracted from nasopharyngeal swabs collected in 2017 spiked with known concentrations of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Each primer–probe set was performed using 24 technical replicates of pooled-swab RNA without spiking SARS-CoV-2 RNA (‘No virus’; six replicates with four independent pools each of four swabs) and eight replicates (two replicates with four independent pools each of four swabs) spiked with 100–102 viral RNA copies μl–1 of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. ND, not detected. Solid lines indicate the median and dashed lines indicate the detection limit. Data used to make this figure can be found in Source Data Fig. 2.

Clinical evaluation of US CDC primer–probe sets

For the US CDC assay, we found that the 2019-nCoV_N1 (N1) primer–probe set was more sensitive than the 2019-nCoV_N2 (N2) primer–probe set (Fig. 2). To investigate whether differences in analytical sensitivity between N1 and N2 would cause inconclusive results, we compared results from 172 clinical samples taken during the COVID-19 pandemic (Fig. 3). We tested RNA from nasopharyngeal swabs, saliva, urine and rectal swabs from patients with COVID-19 and healthcare workers enrolled in our research protocol at Yale-New Haven Hospital. We found that more samples had lower Ct values (more efficient virus detection) using the N1 primer–probe set as compared to N2, again showing that N1 is more sensitive for SARS-CoV-2 detection (Fig. 3a). When the N2 set had lower Ct values, each instance was paired with N1 not detected (>45 Ct), indicating that the N1 set had a more distinct separation between positive and negative values (Fig. 3b). When we look at the US CDC assay outcomes, which take into account both N1 and N2 results, only one out of 172 tests was deemed inconclusive due to N1 being negative (>40 Ct) and N2 being positive (<40 Ct; Table 1). We found more inconclusive results where N1 was the only positive set at a cut-off of both 40 Ct (3/172) and 38 Ct (5/172) (Table 1), probably because the N1 primer–probe set is more sensitive. Overall, we found inconclusive results from <3% of the tested clinical samples that had low (35–40 Ct) or no (>40 Ct) virus detection using the US CDC primer–probe sets, indicating that the US CDC N1 and N2 primer–probe sets are consistent at differentiating between true negatives and positives.

a,b, Clinical samples either negative or low positive for SARS-CoV-2 were used to determine whether differences between the analytical sensitivities of the US CDC N1 and N2 primers produced inconclusive results. a, Ct values for testing of the same 172 clinical samples using the N1 and N2 primer–probe sets. b, We compared Ct values obtained with the two primer–probe sets for clinical samples with Ct values >35. N1, 2019-nCoV_N1; N2, 2019-nCoV_N2; ND, not detected. Solid lines indicate the median and dashed lines indicate the detection limit. Data used to make this figure can be found in Source Data Fig. 3.

Lower sensitivity of RdRp-SARSr (Charité) primer–probe set

To further investigate the relatively low sensitivity of the RdRp-SARSr (Charité) primer–probe set, we compared our standardized primer–probe concentrations with the recommended concentrations in the confirmatory (containing both RdRp_SARSr-P1 (probe 1) and RdRp_SARSr-P2 (probe 2)) and discriminatory (probe 2 only, as shown in Figs. 1 and 2) RdRp-SARSr (Charité) assays. We deviated from the recommended concentrations in the original assays to make a fair comparison across primer–probe sets, using 500 nM of each primer and 250 nM of probe 2. To investigate the effect of primer–probe concentration on the ability to detect SARS-CoV-2, we made a direct comparison between (1) our standardized primer (500 nM) and probe 2 (250 nM) concentrations; (2) the recommended concentrations of 600 nM of forward primer, 800 nM of reverse primer and 100 nM of probes 1 and 2 (confirmatory assay); and (3) the recommended concentrations of 600 nM of forward primer, 800 nM of reverse primer and 200 nM of probe 2 (discriminatory assay) per reaction5. We found that adjustment of the primer–probe concentrations or using the combination of probes 1 and 2 did not increase SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection when using tenfold serial dilutions of our RdRp RNA transcripts, or full-length SARS-CoV-2 RNA from cell culture (Extended Data Fig. 2). The Charité Institute of Virology Universitätsmedizin Berlin assay is designed to use the E-Sarbeco primer–probes as an initial screening assay and the RdRp-SARSr primer–probes as a confirmatory test5. Our data suggest that the RdRp-SARSr assay is not a reliable confirmatory assay at <1,000 viral RNA copies μl–1 of extracted nucleic acid.

Mismatches in primer and probe binding regions

As viruses evolve during outbreaks, nucleotide substitutions can emerge in primer or probe binding regions and alter the sensitivity of PCR assays. To investigate whether this had already occurred during the early COVID-19 pandemic, we calculated the accumulated genetic diversity from 992 available SARS-CoV-2 genomes (released as of 22 March 2020; Fig. 4) and compared that to the primer and probe binding regions (Table 2). Thus far, we detected 12 primer–probe nucleotide mismatches that had occurred in at least two of the 992 SARS-CoV-2 genomes. The most potentially problematic mismatch is in the RdRp-SARSr reverse primer (Table 2), which probably explains the sensitivity issues with this set (Figs. 1 and 2). Oddly, the mismatch is not derived from a new variant that has arisen, but rather that the primer contains a degenerate nucleotide (S, binds with G or C) at position 12, and 990 of the 992 SARS-CoV-2 genomes encode for a T at this genome position (Table 2). This degenerate nucleotide appears to have been added to help the primer anneal to SARS-CoV and bat-SARS-related CoV genomes5, seemingly to the detriment of consistent SARS-CoV-2 detection. Earlier in the outbreak, before hundreds of SARS-CoV-2 genomes became available, non-SARS-CoV-2 data were used to infer genetic diversity that could be anticipated during the outbreak. As a result, several of the primers contain degenerate nucleotides (Supplementary Table 4). For RdRp-SARSr, adjustment of the primer (S→A) may resolve its low sensitivity.

A total of 992 SARS-CoV-2 genomes available as of 22 March 2020 (listed in Source Data Fig. 4) were aligned to calculate nucleotide diversity and investigate mismatches with the nine primer–probe sets. Genetic diversity was measured using pairwise identity (%) at each position, disregarding gaps and ambiguous nucleotides. Asterisks at the top indicate primers (green) and probes (red) targeting regions with one or more mismatches. Genomic plots were designed using DNA Features Viewer 3.0.1 in Python v.3.7 (ref. 15). bp, base pairs.

Of the variants that we detected in the primer–probe regions, we found only four in >30 of the 992 SARS-CoV-2 genomes (>3%; Table 2). Most notable was a stretch of three nucleotide substitutions (GGG→AAC) at genome positions 28,881–28,883, which occur in the first three positions of the CCDC-N forward primer binding site. While these substitutions define a large clade that includes ~13% of the available SARS-CoV-2 genomes released as of 22 March 2020, and that have been detected in numerous countries11, their position on the 5′ location of the primer may not be detrimental to sequence annealing and amplification. The other high-frequency variant that we detected was T→C substitution at the eighth position of the binding region of the 2019-nCoV_N3 forward primer, a substitution found in 39 genomes (position 28,688). While this primer could be problematic in regard to detection of viruses with this variant, the CDC revised their assay on 15 March 2020 by removing the 2019-nCoV_N3 primer–probe set12. We found another seven variants in only five or fewer genomes (<0.5%; Table 2), and their minor frequency at present does not pose a major concern for viral detection. This scenario may change if those variants increase in frequency—most of them lie in the second half of the primer binding region and they may decrease primer sensitivity13. The WA1_USA strain8 (GenBank: MN985325) that we used as a reference for our comparisons contains only the mismatch with the RdRp reverse primer (T at position 15,519), and therefore we cannot directly assess the impact of the other variants. Continued monitoring is required of SARS-CoV-2 evolution (for example, gisaid.org), and how arising variants may alter PCR detection.

Discussion

Our study provides a comprehensive and independent comparison of analytical performance of primer–probe sets for SARS-CoV-2 testing in various parts of the world. Our findings show a high similarity in the analytical sensitivities for SARS-CoV-2 detection, which indicates that outcomes of different assays are comparable. The primary exception to this is the RdRp-SARSr (Charité) primer–probe set, which had the lowest sensitivity, as also shown by an independent study14, probably stemming from a mismatch in the reverse primer. In the United States, we recommend using the US CDC SARS-CoV-2 assay because: (1) we found similar analytical sensitivity as compared to the other three assays; (2) we detected a low rate of inconclusive results with low-virus clinical samples; (3) it includes a human RNase P primer–probe set (RP) that allows for quality control of RNA extraction methods; and (4) its widespread use in the United States makes it easier to compare results. In other regions of the world, however, a different test may be preferable based on existing usage.

Our study has limitations to consider. We standardized the concentration of primers and probes, PCR kits and thermocycler conditions for direct comparison of primer–probe sets used in four common RT–qPCR assays for detection of SARS-CoV-2. By standardizing the PCRs, we deviated from some of the recommended conditions, which means that not all of our results can be directly transferable to how the assays were intended in clinical diagnostic settings. For instance, we selected an annealing temperature of 55 °C which is lower than that recommended for the assays developed by Charité (58 °C)5 and HKU (60 °C)4, but similar to that developed by US CDC (55 °C)6. No specific PCR conditions were reported for the assay developed by the China CDC7. We found that the two assays with higher annealing temperatures (Charité and HKU) had high analytical sensitivity and no background amplification, which suggests that our standardized annealing temperature probably did not have a large effect on our findings. In addition, we selected one RT–qPCR kit (Luna Universal Probe One-step RT–qPCR) for all comparisons. We selected this kit specifically because it was not approved by the US Federal Drug Administration for SARS-CoV-2 diagnostics and thus our research would not compete with clinical diagnostic laboratories for resources. In doing so, we provide an alternative protocol for SARS-CoV-2 RT–qPCR for research testing (Supplementary File 1), which is especially helpful as more resources are required to expand testing around the world. Finally, we performed all of our RT–qPCR tests on one thermocycler (BioRad CFX). It is possible that our standardization methods may have influenced analytical performance of the tested primer–probe sets, and our results may not directly apply to other PCR kits or thermocyclers9. Thus, we strongly urge that each laboratory should locally validate analytical sensitivities and positive–negative cut-off values when establishing these assays, which can be performed using our RNA transcripts and study framework.

Methods

Ethics

Residual de-identified nasopharyngeal samples collected during 2017 (pre-COVID-19) were obtained from the Yale-New Haven Hospital Clinical Virology Laboratory. In accordance with the guidelines of the Yale Human Investigations Committee, this work with de-identified samples is considered as non-human subjects research. These samples were used to create the mock substrate for the SARS-CoV-2 spike-in experiments. Collection of clinical samples from patients with COVID-19 and healthcare workers at the Yale-New Haven Hospital was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Yale Human Research Protection Program (no. FWA00002571, Protocol ID 2000027690). Written consent was obtained from all patients and healthcare workers. These samples were used to test the US CDC 2019-nCoV_N1 and 2019-nCoV_N2 primer–probe sets.

Generation of RNA transcript standards

We generated RNA transcript standards for each of the five genes targeted by the diagnostic RT–qPCR assays using T7 transcription; a detailed protocol can be found in ref. 10. Briefly, complementary DNA was synthesized from full-length SARS-CoV-2 RNA (WA1_USA strain from UTMB; GenBank: MN985325). Using PCR, we amplified the nsp10, RdRp, nsp14, E and N genes with specifically designed primers (Supplementary Table 2). We purified PCR products using the Mag-Bind TotalPure NGS kit (Omega Bio-tek) and quantified products using the Qubit High Sensitivity DNA kit (ThermoFisher Scientific). We determined fragment sizes using the DNA 1000 kit on the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent). After quantification, we transcribed 100–200 ng of each purified PCR product into RNA using the Megascript T7 kit (ThermoFisher Scientific). Although RNA transcripts were DNase treated with TURBO DNase, low concentrations of residual DNA may still have been present. We quantified RNA transcripts using the Qubit High sensitivity RNA kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) and checked quality using the Bioanalyzer RNA pico 6000 kit. For each of the RNA transcript standards (Supplementary Table 3), we calculated the number of viral RNA copies µl–1 using Avogadro’s number. We generated a genomic annotation plot with all newly generated RNA transcript standards and the nine tested primer–probe sets based on the NC_045512 reference genome using the DNA Features Viewer 3.0.1 in Python v.3.7 (Extended Data Fig. 1)15. We generated standard curves for each combination of primer–probe set with its corresponding RNA transcript standard, using standardized RT–qPCR conditions as described below.

RT–qPCR conditions

To make a fair comparison among nine primer–probe sets (Supplementary Table 1), we used the same RT–qPCR reagents and conditions for all comparisons. We used the Luna Universal Probe One-step RT–qPCR kit (New England Biolabs) with 5 µl of RNA and standardized primer and probe concentrations of 500 nM of forward and reverse primer, and 250 nM of probe for all comparisons. PCR cycler conditions were reverse transcribed for 10 min at 55 °C and initial denaturation for 1 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles (45 cycles for clinical samples) of 10 s at 95 °C and 30 s at 55 °C on the Biorad CFX96 qPCR machine (Biorad). We applied fluorescence drift correction for plates with autofluorescence and refrained from manual adjustment of the threshold. A detailed protocol can be found in Supplementary File 1. We calculated analytical efficiency (E) of RT–qPCR assays tested with corresponding RNA transcript standards using the following formula:16,17

Validation with SARS-CoV-2 RNA and pre-COVID-19 samples

We prepared mock samples by extracting RNA from de-identified nasopharyngeal swabs collected in 2017 (pre-COVID-19) from hospital patients with respiratory disease using the MagMAX Viral/Pathogen Nucleic Acid Isolation kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s protocol. We used 300 µl of sample and eluted in 75 µl. We compared analytical efficiency and sensitivity of primer–probe sets by testing tenfold dilutions (106–100 viral RNA copies μl–1) of SARS-CoV-2 RNA as well as the SARS-CoV-2 mock samples spiked with RNA after extraction (eluates pooled from 12 individuals), in duplicate. In addition, we pooled eluates from four patients to create four independent pools (16 individuals total) and spiked these mock samples with tenfold dilutions of SARS-CoV-2 RNA (100–102 viral RNA copies μl–1) to determine the lower detection limit of each primer–probe set. We tested RNA-spiked mock samples from each of the four independent pools in duplicate (in total eight samples). Lastly, we tested mock samples (no spiked-in virus) from each pool for six replicates (in total 24 samples per primer–probe set) to test for potential background amplification.

Clinical samples

Clinical samples from patients diagnosed with COVID-19 and healthcare workers were obtained from the Yale-New Haven Hospital. We extracted nucleic acid from nasopharyngeal swabs, saliva, urine and rectal swabs using the MagMax Viral/Pathogen Nucleic Acid Isolation kit following a slightly adjusted protocol18. We used 300 µl of each sample and eluted in 75 µl. We utilized the Luna Universal Probe One-step RT–qPCR kit with standardized primer and probe concentrations of 500 nM of forward and reverse primer, and 250 nM of probe, for the 2019-nCoV_N1, 2019-nCoV_N2 and RP (human control) primer–probe sets to detect SARS-CoV-2 in each sample. PCR cycler conditions were reverse transcription for 10 min at 55 °C, initial denaturation for 1 min at 95 °C, followed by 45 cycles of 10 s at 95 °C and 30 s at 55 °C on the Biorad CFX96 qPCR machine (Biorad). All figures were made with GraphPad Prism 8.3.0.

Mismatches in primer and probe binding regions

We investigated mismatches in primer binding regions by calculating pairwise identities (%) for each nucleotide position in binding sites of assay primers and probes. Ignoring gaps and ambiguous bases, we compared all possible pairs of nucleotides in all columns of a multiple-sequence alignment including all available SARS-CoV-2 genomes from GISAID (as of 22 March 2020; Source Data Fig. 4). We assigned a score of 1 for each identical pair of bases and divided the final score by the total number of valid nucleotide pairs, to finally express pairwise identities as percentages. Pairwise identity <100% indicates mismatches between primers or probes and some SARS-CoV-2 genomes. We calculated mismatch frequencies and reported absolute and relative frequencies for mismatches with frequency >0.1%. The DNA Features Viewer 3.0.1 package in Python v.3.7 was used to generate the diversity plot (Fig. 4)15.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data are included in this article, the supplementary files and the source data. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Gorbalenya, A. E. et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: the species and its viruses – a statement of the Coronavirus Study Group. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.07.937862 (2020).

Wu, F. et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature 579, 265–269 (2020).

Zhou, P. et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 579, 270–273 (2020).

Chu, D. K. W. et al. Molecular diagnosis of a novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) causing an outbreak of pneumonia. Clin. Chem. 66, 549–555 (2020).

Corman, V. M. et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT–PCR. Euro Surveill. 25, 2000045 (2020).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Research use only 2019—novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) real-time RT–PCR primers and probes (2020); https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/rt-pcr-panel-primer-probes.html

National Institute for Viral Disease Control and Prevention. Specific primers and probes for detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2020); http://ivdc.chinacdc.cn/kyjz/202001/t20200121_211337.html

Harcourt, J. et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 from patient with 2019 novel coronavirus disease, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 26, 1266–1273 (2020).

Svec, D., Tichopad, A., Novosadova, V., Pfaffl, M. W. & Kubista, M. How good is a PCR efficiency estimate? Recommendations for precise and robust qPCR efficiency assessments. Biomol. Detect. Quantif. 3, 9–16 (2015).

Vogels, C. B. F., Fauver, J. R., Ott, I. & Grubaugh, N. D. Generation of SARS-COV-2 RNA transcript standards for qRT–PCR detection assay. protocols.io https://doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.bdv6i69e (2020).

The Nextstrain team. Genomic epidemiology of novel coronavirus—global subsampling (2020); https://nextstrain.org/ncov?c=gt-ORF14_50

Genomeweb. CDC revises SARS-CoV-2 assay protocol; surveillance testing on track to start next week. 360Dx https://www.360dx.com/pcr/cdc-revises-sars-cov-2-assay-protocol-surveillance-testing-track-start-next-week (2020).

Bru, D., Martin-Laurent, F. & Philippot, L. Quantification of the detrimental effect of a single primer–template mismatch by real-time PCR using the 16S rRNA gene as an example. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 1660–1663 (2008).

Nalla, A. K. et al. Comparative performance of SARS-CoV-2 detection assays using seven different primer/probe sets and one assay kit. J. Clin. Microbiol. 58, e00557-20 (2020).

Zulkower, V. & Rosser, S. DNA Features Viewer, a sequence annotations formatting and plotting library for Python. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.09.900589 (2020).

Broeders, S. et al. Guidelines for validation of qualitative real-time PCR methods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 37, 115–126 (2014).

Ginzinger, D. G. Gene quantification using real-time quantitative PCR: an emerging technology hits the mainstream. Exp. Hematol. 30, 503–512 (2002).

Ott, I. M., Vogels, C. B. F., Grubaugh, N. D., & Wyllie, A. L. Saliva collection and RNA extraction for SARS-CoV-2 detection. protocols.io https://doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.bh6mj9c6 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank K. Plante and the University of Texas Medical Branch World Reference Center for Emerging Viruses for providing SARS-CoV-2 RNA, the Yale COVID-19 Laboratory Working Group for technical support, P. Jack and S. Taylor for discussions and A. Greninger and X. Lu for feedback on a previous version of this manuscript. We also thank scientists from around the world who openly shared their SARS-CoV-2 genomic data on GISAID, and they are acknowledged in Source Data Fig. 4. This research was funded by generous support from the Yale Institute for Global Health and the Yale School of Public Health start-up package provided to N.D.G. C.B.F.V. is supported by NWO Rubicon (no. 019.181EN.004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.B.F.V., A.F.B., J.R.F. and N.D.G. designed the study. N.R.C. and E.F.F. collected pre-COVID-19 nasopharyngeal swabs. C.B.F.V., A.L.W., I.M.O., C.C.K., M.E.P., A.C.-M., M.C.M., A.J.M., J.K., P.L., A.L.-C., X.J., D.J.K., E.K., T.M., M.M., J.E.O., A.P., J.S., E.S., T.T., M. Taura, M. Tukuyama, A.V., O.-E.W., P.W., Y.Y., E.B.W., S.L., R.E., B.G., P.V., C.O., J.F., S.B., S.F., C.S.D.C., A.I., A.I.K., M.L.L. and N.D.G. contributed to collection of clinical data. C.B.F.V. performed experiments. C.B.F.V., A.F.B. and N.D.G. analysed the data and wrote the first draft. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.L.W. has received research funding through grants from Pfizer to Yale and has received consulting fees for participation in advisory boards for Pfizer. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Generation of RNA transcript standards for validation of SARS-CoV-2 RT-qPCR assays.

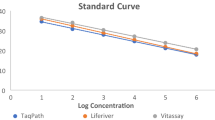

a, SARS-CoV-2 genome locations of generated RNA transcript standards for the non-structural protein 10 (nsp10), RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), non-structural protein 14 (nsp14), envelope (E), and nucleocapsid (N) genes and the nine primer-probe sets used RT-qPCR assays. b, The slope, intercept, R2, and efficiency of RT-qPCR using tenfold dilutions (100–106 viral RNA copies/μL) of RNA transcript standards with the corresponding primer-probe sets. Shown are mean Ct values based on 2 technical replicates. The primer-probe sets are numbered as shown in panel A. The RNA transcript primers and sequences can be found in Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Table 3, respectively. Data used to make this figure can be found in Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1.

Extended Data Fig. 2 No effect of different concentrations of RdRp-SARSr primers and probes on analytical sensitivity.

Low performance of the standardized RdRp-SARSr primer-probe set triggered us to further investigate the effect of primer concentrations. We compared our standardized primer-probe concentrations (500 nM of forward and reverse primers, and 250 nM of probe) with the recommended concentrations in the confirmatory assay (600 nM of forward primer, 800 nM of reverse primer, 100 nM of probe 1, and 100 nM of probe 2), and the discriminatory assay (600 nM of forward primer, 800 nM of reverse primer, and 200 nM of probe 2) as developed by the Charité Institute of Virology Universitätsmedizin Berlin. Standard curves for both RdRp-transcript standard and full-length SARS-CoV-2 RNA are similar, which indicates that higher primer concentrations did not improve the performance of the RdRp-SARSr set. Symbol indicates tested sample type (circles = RdRp transcript standard, and squares = full-length SARS-CoV-2 RNA from cell culture) and colors indicate the different primer and probe concentrations. Data used to make this figure can be found in Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1–4 and File 1.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Supporting data for Fig. 1.

Source Data Fig. 2

Supporting data for Fig. 2.

Source Data Fig. 3

Supporting data for Fig. 3.

Source Data Fig. 4

Supporting data for Fig. 4.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Supporting data for Extended Data Fig. 1.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Supporting data Extended Data Fig. 2.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vogels, C.B.F., Brito, A.F., Wyllie, A.L. et al. Analytical sensitivity and efficiency comparisons of SARS-CoV-2 RT–qPCR primer–probe sets. Nat Microbiol 5, 1299–1305 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-020-0761-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-020-0761-6

This article is cited by

-

Fast and sensitive CRISPR detection by minimized interference of target amplification

Nature Chemical Biology (2024)

-

Preamplification-free viral RNA diagnostics with single-nucleotide resolution using MARVE, an origami paper-based colorimetric nucleic acid test

Nature Protocols (2024)

-

SARS-CoV-2 genome incidence on the inanimate surface of the material used in the flow of biological samples from the collection point to the testing unit

Irish Journal of Medical Science (1971 -) (2024)

-

Sensitive Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Using an Aptamer Sandwich Assay-Based Electrochemical Biosensor

BioChip Journal (2024)

-

The development of a highly sensitive and quantitative SARS-CoV-2 rapid antigen test applying newly developed monoclonal antibodies to an automated chemiluminescent flow-through membrane immunoassay device

BMC Immunology (2023)