Key Points

-

Gout is the most common form of inflammatory arthritis and is caused by the deposition of monosodium urate crystals in and around the joints

-

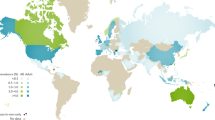

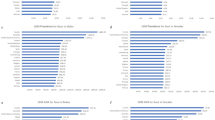

The reported prevalence of gout worldwide ranges from 0.1% to approximately 10%, and the incidence from 0.3 to 6 cases per 1,000 person-years

-

Both prevalence and incidence of gout are increasing in many developed countries

-

The prevalence and incidence of gout is highly variable across various regions of the world, with developed countries generally having higher prevalence than developing countries

-

A combination of genetic and environmental factors contribute to the development of gout

-

Major risk factors for gout include hyperuricaemia, genetics, dietary factors, medications, comorbidities and exposure to lead

Abstract

Gout is a crystal-deposition disease that results from chronic elevation of uric acid levels above the saturation point for monosodium urate (MSU) crystal formation. Initial presentation is mainly severely painful episodes of peripheral joint synovitis (acute self-limiting 'attacks') but joint damage and deformity, chronic usage-related pain and subcutaneous tophus deposition can eventually develop. The global burden of gout is substantial and seems to be increasing in many parts of the world over the past 50 years. However, methodological differences impair the comparison of gout epidemiology between countries. In this comprehensive Review, data from epidemiological studies from diverse regions of the world are synthesized to depict the geographic variation in gout prevalence and incidence. Key advances in the understanding of factors associated with increased risk of gout are also summarized. The collected data indicate that the distribution of gout is uneven across the globe, with prevalence being highest in Pacific countries. Developed countries tend to have a higher burden of gout than developing countries, and seem to have increasing prevalence and incidence of the disease. Some ethnic groups are particularly susceptible to gout, supporting the importance of genetic predisposition. Socioeconomic and dietary factors, as well as comorbidities and medications that can influence uric acid levels and/or facilitate MSU crystal formation, are also important in determining the risk of developing clinically evident gout.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kuo, C. F., Grainge, M. J., Mallen, C., Zhang, W. & Doherty, M. Comorbidities in patients with gout prior to and following diagnosis: case-control study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206410.

Puig, J. G. & Martinez, M. A. Hyperuricemia, gout and the metabolic syndrome. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 20, 187–191 (2008).

Abbott, R. D., Brand, F. N., Kannel, W. B. & Castelli, W. P. Gout and coronary heart disease: the Framingham Study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 41, 237–242 (1988).

De Vera, M. A., Rahman, M. M., Bhole, V., Kopec, J. A. & Choi, H. K. Independent impact of gout on the risk of acute myocardial infarction among elderly women: a population-based study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69, 1162–1164 (2010).

Krishnan, E., Baker, J. F., Furst, D. E. & Schumacher, H. R. Gout and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. Arthritis Rheum. 54, 2688–2696 (2006).

Kuo, C. F. et al. Risk of myocardial infarction among patients with gout: a nationwide population-based study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 52, 111–117 (2013).

Yu, K. H. et al. Risk of end-stage renal disease associated with gout: a nationwide population study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 14, R83 (2012).

So, A. Epidemiology: Gout—bad for the heart as well as the joint. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 6, 386–387 (2010).

Community Oriented Program for Control of Rheumatic Diseases (COPCORD). COPCORD Website[online], (2015).

Roddy, E., Zhang, W. & Doherty, M. The changing epidemiology of gout. Nat. Clin. Pract. Rheumatol. 3, 443–449 (2007).

Doherty, M. et al. Gout: why is this curable disease so seldom cured? Ann. Rheum. Dis. 71, 1765–1770 (2012).

Chang, S. J. et al. High prevalence of gout and related risk factors in Taiwan's Aborigines. J. Rheumatol. 24, 1364–1369 (1997).

Chou, C. T. & Lai, J. S. The epidemiology of hyperuricaemia and gout in Taiwan aborigines. Br. J. Rheumatol. 37, 258–262 (1998).

Tu, F. Y. et al. Prevalence of gout with comorbidity aggregations in southern Taiwan. Joint Bone Spine 82, 45–51 (2015).

Rose, B. S. & Prior, I. A. A surgery of rheumatism in a rural New Zealand Maori community. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 22, 410–415 (1963).

Brauer, G. W. & Prior, I. A. A prospective study of gout in New Zealand Maoris. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 37, 466–472 (1978).

Klemp, P., Stansfield, S. A., Castle, B. & Robertson, M. C. Gout is on the increase in New Zealand. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 56, 22–26 (1997).

Pascart, T., Oehler, E. & Flipo, R. M. Gout in French Polynesia: a survey of common practices. Joint Bone Spine 81, 374–375 (2014).

Khaltaev, N. & Benevolenskaya, L. I. in The Primary Prevention of Rheumatic Diseases (Ed. Wigley, R. D.) 11–20 (Parthenon Publishing Group, 1994).

Obregon-Ponce, A., Iraheta, I., Garcia-Ferrer, H., Mejia, B. & Garcia-Kutzbach, A. Prevalence of musculoskeletal diseases in Guatemala, Central America: the COPCORD study of 2 populations. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 18, 170–174 (2012).

Davatchi, F. et al. WHO–ILAR COPCORD Study (stage 1, urban study) in Iran. J. Rheumatol. 35, 1384 (2008).

Sandoughi, M. et al. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders in southeastern Iran: a WHO–ILAR COPCORD study (stage 1, urban study). Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 16, 509–517 (2013).

Forghanizadeh, J. et al. Prevalence of rheumatic disease in Fasham. Razi Journal of Medical Sciences 3, 182–191 (1995).

Moghimi, N. et al. WHO–ILAR COPCORD study (stage 1, urban study) in Sanandaj, Iran. Clin. Rheumatol. 34, 535–543 (2013).

Davatchi, F. et al. Effect of ethnic origin (Caucasians versus Turks) on the prevalence of rheumatic diseases: a WHO–ILAR COPCORD urban study in Iran. Clin. Rheumatol. 28, 1275–1282 (2009).

Veerapen, K., Wigley, R. D. & Valkenburg, H. Musculoskeletal pain in Malaysia: a COPCORD survey. J. Rheumatol. 34, 207–213 (2007).

Dans, L. F., Tankeh-Torres, S., Amante, C. M. & Penserga, E. G. The prevalence of rheumatic diseases in a Filipino urban population: a WHO–ILAR COPCORD Study. World Health Organization. International League of Associations for Rheumatology. Community Oriented Programme for the Control of the Rheumatic Diseases. J. Rheumatol. 24, 1814–1819 (1997).

Al-Arfaj, A. S. Hyperuricemia in Saudi Arabia. Rheumatol. Int. 20, 61–64 (2001).

Cakir, N. et al. The prevalences of some rheumatic diseases in western Turkey: Havsa study. Rheumatol. Int. 32, 895–908 (2012).

Muller, A. S. Population Studies on the Prevalence of Rheumatic Diseases in Liberia and Nigeria. Thesis, University of Leiden (1970).

Beighton, P., Soskolne, C. L., Solomon, L. & Sweet, B. Serum uric-acid levels in a Nama (Hottentot) community in South-West-Africa. S. Afr. J. Sci. 70, 281–283 (1974).

Beighton, P., Daynes, G. & Soskolne, C. L. Serum uric acid concentrations in a Xhosa community in the Transkei of Southern Africa. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 35, 77–80 (1976).

Lutalo, S. K. Chronic inflammatory rheumatic diseases in black Zimbabweans. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 44, 121–125 (1985).

Beighton, P., Solomon, L., Soskolne, C. L. & Sweet, M. B. Rheumatic disorders in the South African Negro. Part IV. Gout and hyperuricaemia. S. Afr. Med. J. 51, 969–972 (1977).

Wijnands, J. M. et al. Determinants of the prevalence of gout in the general population: a systematic review and meta-regression. Eur. J. Epidemiol. (2014).

Zhu, Y., Pandya, B. J. & Choi, H. K. Prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2008 Arthritis Rheum. 63, 3136–3141 (2011).

Badley E. D. M. Arthritis in Canada: an ongoing challenge (Health Canada, Ottawa, 2003).

Anagnostopoulos, I. et al. The prevalence of rheumatic diseases in central Greece: a population survey. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 11, 98 (2010).

Kuo, C. F., Grainge, M. J., Mallen, C., Zhang, W. & Doherty, M. Rising burden of gout in the UK but continuing suboptimal management: a nationwide population study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204463.

Sicras-Mainar, A., Navarro-Artieda, R. & Ibanez-Nolla, J. Resource use and economic impact of patients with gout: a multicenter, population-wide study [article in English, Spanish]. Reumatol. Clin. 9, 94–100 (2013).

Picavet, H. S. & Hazes, J. M. Prevalence of self reported musculoskeletal diseases is high. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 62, 644–650 (2003).

Annemans, L. et al. Gout in the UK and Germany: prevalence, comorbidities and management in general practice 2000–2005 Ann. Rheum. Dis. 67, 960–966 (2008).

Bardin, T. et al. Prevalence of gout in the adult population of France in 2013 [abstract]. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73 (Suppl. 2), 787–788 (2014).

Trifiro, G. et al. Epidemiology of gout and hyperuricaemia in Italy during the years 2005–2009: a nationwide population-based study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 72, 694–700 (2013).

Reis, C. & Viana Queiroz, M. Prevalence of self-reported rheumatic diseases in a Portuguese population. Acta Reumatol. Port. 39, 54–59 (2014).

Hanova, P., Pavelka, K., Dostal, C., Holcatova, I. & Pikhart, H. Epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis and gout in two regions of the Czech Republic in a descriptive population-based survey in 2002–2003. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 24, 499–507 (2006).

Minaur, N., Sawyers, S., Parker, J. & Darmawan, J. Rheumatic disease in an Australian Aboriginal community in North Queensland, Australia. A WHO–ILAR COPCORD survey. J. Rheumatol. 31, 965–972 (2004).

Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Health Survey, summary of results, Australia, 1995 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, 1996).

Winnard, D. et al. National prevalence of gout derived from administrative health data in Aotearoa New Zealand. Rheumatology (Oxford) 51, 901–909 (2012).

Kawasaki T. S. K. Epidemiology survey of gout using residents' health checks. Gou t and Nucleic Acid Metabolism 30, 66 (2006).

Lee, C. H. & Sung, N. Y. The prevalence and features of Korean gout patients using the National Health Insurance Corporation Database. J. Korean Rheum. Assoc. 18, 94–100 (2011).

Census and Statistics Department. Special Topics Report No. 27 on Social Statistics: persons with disabilities and chronic diseases (Government of Hong Kong Special Adminstrative Region, 2001).

Teng, G. G. et al. Mortality due to coronary heart disease and kidney disease among middle-aged and elderly men and women with gout in the Singapore Chinese Health Study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 71, 924–928 (2012).

Kuo, C. F. et al. Familial aggregation of gout and relative genetic and environmental contributions: a nationwide population study in Taiwan. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 74, 369–374 (2015).

Isomäki, H. A. & Takkunen, H. Gout and hyperuricemia in a Finnish rural population. Acta Rheumatol. Scand. 15, 112–120 (1969).

Popert, A. J. & Hewitt, J. V. Gout and hyperuricaemia in rural and urban populations. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 21, 154–163 (1962).

Mikuls, T. R. et al. Gout epidemiology: results from the UK General Practice Research Database, 1990–1999 Ann. Rheum. Dis. 64, 267–72 (2005).

Robinson, P. C., Taylor, W. J. & Merriman, T. R. Systematic review of the prevalence of gout and hyperuricaemia in Australia. Intern. Med. J. 42, 997–1007 (2012).

Chou, C. T. et al. Prevalence of rheumatic diseases in Taiwan: a population study of urban, suburban, rural differences. J. Rheumatol. 21, 302–306 (1994).

Lin, K. C., Lin, H. Y. & Chou, P. Community based epidemiological study on hyperuricemia and gout in Kin-Hu, Kinmen. J. Rheumatol. 27, 1045–1050 (2000).

Chang, H. Y., Pan, W. H., Yeh, W. T. & Tsai, K. S. Hyperuricemia and gout in Taiwan: results from the Nutritional and Health Survey in Taiwan (1993–1996). J. Rheumatol. 28, 1640–1646 (2001).

Chuang, S. Y., Lee, S. C., Hsieh, Y. T. & Pan, W. H. Trends in hyperuricemia and gout prevalence: Nutrition and Health Survey in Taiwan from 1993–1996 to 2005–2008 Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 20, 301–8 (2011).

Kuo, C. F. et al. Epidemiology and management of gout in Taiwan: a nationwide population study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 17, 13 (2015).

Pfleger, B. Burden and control of musculoskeletal conditions in developing countries: a joint WHO/ILAR/BJD meeting report. Clin. Rheumatol. 26, 1217–1227 (2007).

Cardiel, M. H. & Rojas-Serrano, J. Community based study to estimate prevalence, burden of illness and help seeking behavior in rheumatic diseases in Mexico City. A COPCORD study. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 20, 617–624 (2002).

Pelaez-Ballestas, I. et al. Epidemiology of the rheumatic diseases in Mexico. A study of 5 regions based on the COPCORD methodology. J. Rheumatol. Suppl. 86, 3–8 (2011).

Reyes-Llerena, G. A. et al. Community-based study to estimate prevalence and burden of illness of rheumatic diseases in Cuba: a COPCORD study. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 15, 51–55 (2009).

Granados, Y. et al. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders and rheumatic diseases in an urban community in Monagas State, Venezuela: a COPCORD study. Clin. Rheumatol. (2014).

Bremner, J. M. & Lawrence, J. S. Population studies of serum uric acid. Proc. R. Soc. Med. 59, 319–325 (1966).

Darmawan, J., Valkenburg, H. A., Muirden, K. D. & Wigley, R. D. The epidemiology of gout and hyperuricemia in a rural population of Java. J. Rheumatol. 19, 1595–1599 (1992).

Haq, S. A. et al. Prevalence of rheumatic diseases and associated outcomes in rural and urban communities in Bangladesh: a COPCORD study. J. Rheumatol. 32, 348–353 (2005).

Dai, S. M. et al. Prevalence of rheumatic symptoms, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and gout in Shanghai, China: a COPCORD study. J. Rheumatol. 30, 2245–2251 (2003).

Chen, S., Du, H., Wang, Y. & Xu, L. The epidemiology study of hyperuricemia and gout in a community population of Huangpu District in Shanghai. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 111, 228–230 (1998).

Chopra, A. et al. Prevalence of rheumatic diseases in a rural population in western India: a WHO–ILAR COPCORD Study. J. Assoc. Physicians India 49, 240–246 (2001).

Farooqi, A. & Gibson, T. Prevalence of the major rheumatic disorders in the adult population of north Pakistan. Br. J. Rheumatol. 37, 491–495 (1998).

Chaiamnuay, P., Darmawan, J., Muirden, K. D. & Assawatanabodee, P. Epidemiology of rheumatic disease in rural Thailand: a WHO–ILAR COPCORD study. Community Oriented Programme for the Control of Rheumatic Disease. J. Rheumatol. 25, 1382–1387 (1998).

Minh Hoa, T. T. et al. Prevalence of the rheumatic diseases in urban Vietnam: a WHO–ILAR COPCORD study. J. Rheumatol. 30, 2252–2256 (2003).

Miao, Z. et al. Dietary and lifestyle changes associated with high prevalence of hyperuricemia and gout in the Shandong coastal cities of Eastern China. J. Rheumatol. 35, 1859–1864 (2008).

Nan, H. et al. The prevalence of hyperuricemia in a population of the coastal city of Qingdao, China. J. Rheumatol. 33, 1346–1350 (2006).

Zeng, Q. et al. Primary gout in Shantou: a clinical and epidemiological study. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 116, 66–69 (2003).

Li, R. et al. Epidemiology of eight common rheumatic diseases in China: a large-scale cross-sectional survey in Beijing. Rheumatology (Oxford) 51, 721–729 (2012).

Mahajan, A., Jasrotia, D. S., Manhas, A. S. & Jamwal, S. S. Prevalence of major rheumatic disorders in Jammu. J. Med. Educ. Res. (2003).

Tsitlanadze, V. G., Kartvelishvili, E., Shakulashvili, N. A. & Shalamberidze, L. P. Incidence and various risk factors for gout in the Georgian SSR [article in Russian]. Ter. Arkh. 59, 18–20 (1987).

Sagna, Y. et al. Prevalence and associated risk factors of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in urban population; a study from Burkina Faso. J. Diabetol. 2, 4 (2014).

Mijiyawa, M. & Oniankitan, O. Risk factors for gout in Togolese patients. Joint Bone Spine 67, 441–445 (2000).

Burch, T. A., O'Brien, W. M., Need, R. & Kurland, L. T. Hyperuricaemia and gout in the Mariana Islands. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 25, 114–116 (1966).

Bennett, P. H. & Wood, P. H. N. Population studies of the rheumatic diseases: proceedings of the third international symposium, New York, June 5th–10th, 1966 (Excerpta Medica Foundation, 1968).

Prior, I. A., Rose, B. S., Harvey, H. P. & Davidson, F. Hyperuricaemia, gout, and diabetic abnormality in Polynesian people. Lancet 1, 333–338 (1966).

Zimmet, P. Z., Whitehouse, S., Jackson, L. & Thoma, K. High prevalence of hyperuricaemia and gout in an urbanised Micronesian population. Br. Med. J. 1, 1237–1239 (1978).

Jackson, L. et al. Hyperuricaemia and gout in Western Samoans. J. Chronic Dis. 34, 65–75 (1981).

O'Sullivan, J. B. Gout in a New England town: a prevalence study in Sudbury, Massachusetts. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 31, 166–169 (1972).

Maynard, J. W. et al. Racial differences in gout incidence in a population-based cohort: Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 179, 576–583 (2014).

Arromdee, E., Michet, C. J., Crowson, C. S., O'Fallon, W. M. & Gabriel, S. E. Epidemiology of gout: is the incidence rising? J. Rheumatol. 29, 2403–2406 (2002).

Stewart, O. J. & Silman, A. J. Review of UK data on the rheumatic diseases--4. Gout. Br. J. Rheumatol. 29, 485–488 (1990).

Elliot, A. J., Cross, K. W. & Fleming, D. M. Seasonality and trends in the incidence and prevalence of gout in England and Wales 1994–2007 Ann. Rheum. Dis. 68, 1728–1733 (2009).

Hall, A. P., Barry, P. E., Dawber, T. R. & McNamara, P. M. Epidemiology of gout and hyperuricemia. A long-term population study. Am. J. Med. 42, 27–37 (1967).

Kippen, I., Klinenberg, J. R., Weinberger, A. & Wilcox, W. R. Factors affecting urate solubility in vitro. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 33, 313–317 (1974).

Lin, K. C., Lin, H. Y. & Chou, P. The interaction between uric acid level and other risk factors on the development of gout among asymptomatic hyperuricemic men in a prospective study. J. Rheumatol. 27, 1501–1505 (2000).

Duskin-Bitan, H. et al. The degree of asymptomatic hyperuricemia and the risk of gout. A retrospective analysis of a large cohort. Clin. Rheumatol. 33, 549–553 (2014).

Zalokar, J., Lellouch, J., Claude, J. R. & Kuntz, D. Serum uric acid in 23,923 men and gout in a subsample of 4,257 men in France. J Chronic Dis. 25, 305–312 (1972).

Campion, E. W., Glynn, R. J. & DeLabry, L. O. Asymptomatic hyperuricemia. Risks and consequences in the Normative Aging Study. Am. J. Med. 82, 421–426 (1987).

Mituszova, M., Judak, A., Poor, G., Gyodi, E. & Stenszky, V. Clinical and family studies in Hungarian patients with gout. Rheumatol. Int. 12, 165–168 (1992).

Blumberg, B. S. Heredity of gout and hyperuricemia. Arthritis Rheum. 8, 627–647 (1965).

Emmerson, B. T. Heredity in primary gout. Australas. Ann. Med. 9, 168–175 (1960).

Hauge, M. & Harvald, B. Heredity in gout and hyperuricemia. Acta Med. Scand. 152, 247–257 (1955).

Smyth, C. J., Cotterman, C. W. & Freyberg, R. H. The genetics of gout and hyperuricaemia. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 7, 248 (1948).

Grahame, R. & Scott, J. T. Clinical survey of 354 patients with gout. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 29, 461–468 (1970).

Copeman, W. S. C. A short history of the gout and the rheumatic diseases (University of California Press, 1964).

Smyth, C. J., Cotterman, C. W. & Freyberg, R. H. The genetics of gout and hyperuricaemia; an analysis of 19 families. J. Clin. Invest. 27, 749–759 (1948).

Cobb, S. The frequency of the rheumatic diseases (Harvard University Press, 1971).

Prior, I. A., Welby, T. J., Ostbye, T., Salmond, C. E. & Stokes, Y. M. Migration and gout: the Tokelau Island migrant study. Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed.) 295, 457–461 (1987).

Choi, H. K., Zhu, Y. & Mount, D. B. Genetics of gout. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 22, 144–151 (2010).

Turner, J. J. et al. UROMODULIN mutations cause familial juvenile hyperuricemic nephropathy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 88, 1398–1401 (2003).

Kottgen, A. et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 18 new loci associated with serum urate concentrations. Nat. Genet. 45, 145–154 (2013).

Phipps-Green, A. J. et al. Twenty-eight loci that influence serum urate levels: analysis of association with gout. Ann. Rheum. Dis. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205877.

Rice, T. et al. Heterogeneity in the familial aggregation of fasting serum uric acid level in five North American populations: the Lipid Research Clinics Family Study. Am. J. Med. Genet. 36, 219–225 (1990).

Nath, S. D. et al. Genome scan for determinants of serum uric acid variability. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 18, 3156–3163 (2007).

Wilk, J. B. et al. Segregation analysis of serum uric acid in the NHLBI Family Heart Study. Hum. Genet. 106, 355–359 (2000).

Hak, A. E., Curhan, G. C., Grodstein, F. & Choi, H. K. Menopause, postmenopausal hormone use and risk of incident gout. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69, 1305–1309 (2010).

Royal College of General Practitioners, Office of Population Censuses and Surveys & Department of Health and Social Security. Morbidity statistics from general practice 1970–1971: socio-economic analyses (H. M. S. O., 1982).

Zollner, N. & Griebsch, A. Diet and gout. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 41, 435–442 (1974).

Gordon, T. & Kannel, W. B. Drinking and its relation to smoking, BP, blood lipids, and uric acid. The Framingham study. Arch. Intern. Med. 143, 1366–1374 (1983).

Choi, H. K., Atkinson, K., Karlson, E. W., Willett, W. & Curhan, G. Purine-rich foods, dairy and protein intake, and the risk of gout in men. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 1093–1103 (2004).

Choi, H. K., Atkinson, K., Karlson, E. W., Willett, W. & Curhan, G. Alcohol intake and risk of incident gout in men: a prospective study. Lancet 363, 1277–1281 (2004).

Choi, H. K. & Curhan, G. Soft drinks, fructose consumption, and the risk of gout in men: prospective cohort study. BMJ 336, 309–312 (2008).

Perheentupa, J. & Raivio, K. Fructose-induced hyperuricaemia. Lancet 2, 528–531 (1967).

Batt, C. et al. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption: a risk factor for prevalent gout with SLC2A9 genotype-specific effects on serum urate and risk of gout. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73, 2101–2106 (2014).

Choi, H. K., Willett, W. & Curhan, G. Coffee consumption and risk of incident gout in men: a prospective study. Arthritis Rheum. 56, 2049–2055 (2007).

Zhang, Y. et al. Cherry consumption and decreased risk of recurrent gout attacks. Arthritis Rheum. 64, 4004–4011 (2012).

Choi, H. K., Gao, X. & Curhan, G. Vitamin C intake and the risk of gout in men: a prospective study. Arch. Intern. Med. 169, 502–507 (2009).

Maynard, J. W. et al. Incident gout in women and association with obesity in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am. J. Med. 125, 717.e9–717.e17 (2012).

McAdams-DeMarco, M. A., Maynard, J. W., Baer, A. N. & Coresh, J. Hypertension and the risk of incident gout in a population-based study: the atherosclerosis risk in communities cohort. J. Clin. Hypertens. (Greenwich) 14, 675–679 (2012).

Rho, Y. H. et al. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with gout: a multicenter study. J. Korean Med. Sci. 20, 1029–1033 (2005).

Cea Soriano, L., Rothenbacher, D., Choi, H. K. & Garcia Rodriguez, L. A. Contemporary epidemiology of gout in the UK general population. Arthritis Res. Ther. 13, R39 (2011).

Domrongkitchaiporn, S. et al. Risk factors for development of decreased kidney function in a southeast Asian population: a 12-year cohort study. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 16, 791–799 (2005).

Obermayr, R. P. et al. Predictors of new-onset decline in kidney function in a general middle-European population. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 23, 1265–1273 (2008).

Obermayr, R. P. et al. Elevated uric acid increases the risk for kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 19, 2407–2413 (2008).

Krishnan, E. Chronic kidney disease and the risk of incident gout among middle-aged men: a seven-year prospective observational study. Arthritis Rheum. 65, 3271–3278 (2013).

Palmer, T. M. et al. Association of plasma uric acid with ischaemic heart disease and blood pressure: mendelian randomisation analysis of two large cohorts. BMJ 347, f4262 (2013).

Hughes, K., Flynn, T., de Zoysa, J., Dalbeth, N. & Merriman, T. R. Mendelian randomization analysis associates increased serum urate, due to genetic variation in uric acid transporters, with improved renal function. Kidney Int. 85, 344–351 (2014).

Lyngdoh, T. et al. Serum uric acid and adiposity: deciphering causality using a bidirectional Mendelian randomization approach. PLoS One 7, e39321 (2012).

Merola, J. F., Wu, S., Han, J., Choi, H. K. & Qureshi, A. A. Psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and risk of gout in US men and women. Ann. Rheum. Dis. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205212.

Reynolds, M. D. Gout and hyperuricemia associated with sickle-cell anemia. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 12, 404–413 (1983).

McAdams-DeMarco, M. A., Maynard, J. W., Coresh, J. & Baer, A. N. Anemia and the onset of gout in a population-based cohort of adults: Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 14, R193 (2012).

Khokhar, N. Gouty arthritis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch. Intern. Med. 142, 838 (1982).

Kuzell, W. C. et al. Some observations on 520 gouty patients. J. Chronic Dis. 2, 645–669 (1955).

Durward, W. F. Letter: Gout and hypothyroidism in males. Arthritis Rheum. 19, 123 (1976).

Erickson, A. R., Enzenauer, R. J., Nordstrom, D. M. & Merenich, J. A. The prevalence of hypothyroidism in gout. Am. J. Med. 97, 231–234 (1994).

See, L. C. et al. Hyperthyroid and hypothyroid status was strongly associated with gout and weakly associated with hyperuricaemia. PLoS One 9, e114579 (2014).

Mariani, L. H. & Berns, J. S. The renal manifestations of thyroid disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 23, 22–26 (2012).

Bruderer, S., Bodmer, M., Jick, S. S. & Meier, C. R. Use of diuretics and risk of incident gout: a population-based case-control study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 66, 185–196 (2014).

Choi, H. K., Soriano, L. C., Zhang, Y. & Rodriguez, L. A. Antihypertensive drugs and risk of incident gout among patients with hypertension: population based case-control study. BMJ 344, d8190 (2012).

McAdams-DeMarco, M. A. et al. A urate gene-by-diuretic interaction and gout risk in participants with hypertension: results from the ARIC study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 72, 701–706 (2013).

Lin, H. Y. et al. Cyclosporine-induced hyperuricemia and gout. N. Engl. J. Med. 321, 287–292 (1989).

Stamp, L., Searle, M., O'Donnell, J. & Chapman, P. Gout in solid organ transplantation: a challenging clinical problem. Drugs 65, 2593–2611 (2005).

So, A. & Thorens, B. Uric acid transport and disease. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 1791–1799 (2010).

Zhang, Y. et al. Low-dose aspirin use and recurrent gout attacks. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73, 385–390 (2014).

Fazio, S. et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of ezetimibe/simvastatin coadministered with extended-release niacin in hyperlipidaemic patients with diabetes or metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 12, 983–993 (2010).

Amodio, M. I., Bengualid, V. & Lowy, F. D. Development of acute gout secondary to pyrazinamide in a patient without a prior history of gout. DICP 24, 1115–1116 (1990).

Rao, T. P. & Schmitt, J. K. Gout secondary to pyrazinamide and ethambutol. Va Med. Q. 123, 271 (1996).

Creighton, S., Miller, R., Edwards, S., Copas, A. & French, P. Is ritonavir boosting associated with gout? Int. J. STD AIDS 16, 362–364 (2005).

Ball, G. V. Two epidemics of gout. Bull. Hist. Med. 45, 401–408 (1971).

Lin, J. L., Tan, D. T., Ho, H. H. & Yu, C. C. Environmental lead exposure and urate excretion in the general population. Am. J. Med. 113, 563–568 (2002).

Krishnan, E., Lingala, B. & Bhalla, V. Low-level lead exposure and the prevalence of gout: an observational study. Ann. Intern. Med. 157, 233–241 (2012).

Shadick, N. A. et al. Effect of low level lead exposure on hyperuricemia and gout among middle aged and elderly men: the normative aging study. J. Rheumatol. 27, 1708–1712 (2000).

Lin, J. L., Lin-Tan, D. T., Hsu, K. H. & Yu, C. C. Environmental lead exposure and progression of chronic renal diseases in patients without diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 277–286 (2003).

Martillo, M. A., Nazzal, L. & Crittenden, D. B. The crystallization of monosodium urate. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 16, 400 (2014).

Burt, H. M. & Dutt, Y. C. Growth of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals: effect of cartilage and synovial fluid components on in vitro growth rates. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 45, 858–864 (1986).

Wilcox, W. R. & Khalaf, A. A. Nucleation of monosodium urate crystals. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 34, 332–339 (1975).

Tak, H. K., Wilcox, W. R. & Cooper, S. M. The effect of lead upon urate nucleation. Arthritis Rheum. 24, 1291–1295 (1981).

Perricone, E. & Brandt, K. D. Enhancement of urate solubility by connective tissue. I. Effect of proteoglycan aggregates and buffer cation. Arthritis Rheum. 21, 453–460 (1978).

Pascual, E. & Ordonez, S. Orderly arrayed deposit of urate crystals in gout suggest epitaxial formation. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 57, 255 (1998).

Simkin, P. A. The pathogenesis of podagra. Ann. Intern. Med. 86, 230–233 (1977).

Zhang, Y. et al. Purine-rich foods intake and recurrent gout attacks. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 71, 1448–1453 (2012).

Neogi, T. et al. Alcohol quantity and type on risk of recurrent gout attacks: an internet-based case-crossover study. Am. J. Med. 127, 311–318 (2014).

Choi, H. K. & Curhan, G. Coffee consumption and risk of incident gout in women: the Nurses' Health Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 92, 922–927 (2010).

Roubenoff, R. et al. Incidence and risk factors for gout in white men. JAMA 266, 3004–3007 (1991).

Hochberg, M. C. et al. Racial differences in the incidence of gout. The role of hypertension. Arthritis Rheum. 38, 628–632 (1995).

Krishnan, E. Gout in African Americans. Am. J. Med. 127, 858–864 (2014).

Currie, W. J. Prevalence and incidence of the diagnosis of gout in Great Britain. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 38, 101–106 (1979).

Isomäki, H., Raunio, J., von Essen, R. & Hämeenkorpi, R. Incidence of inflammatory rheumatic diseases in Finland. Scand. J. Rheumatol 7, 188–192 (1978).

Williams, P. T. Effects of diet, physical activity and performance, and body weight on incident gout in ostensibly healthy, vigorously active men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 87, 1480–1487 (2008).

DeMarco, M. M., Maynard, J. W., Baer, A. N. & Coresh, J. Alcohol intake is associated with incident gout among black and white, men and women in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum. 63 (Suppl. 10), 887 (2011).

Zhang, Y. et al. Alcohol consumption as a trigger of recurrent gout attacks. Am. J. Med. 119, 800.e11–800.e16 (2006).

Bhole, V., de Vera, M., Rahman, M. M., Krishnan, E. & Choi, H. Epidemiology of gout in women: fifty-two-year followup of a prospective cohort. Arthritis. Rheum. 62, 1069–1076 (2010).

Lyu, L. C. et al. A case-control study of the association of diet and obesity with gout in Taiwan. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 78, 690–701 (2003).

Zhang, W. et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part I: Diagnosis. Report of a task force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 65, 1301–1311 (2006).

Kellgren, J. H. et al. (Eds) The epidemiology of chronic rheumatism Vol. 1 (Blackwell, 1963).

Wallace, S. L. et al. Preliminary criteria for the classification of the acute arthritis of primary gout. Arthritis Rheum. 20, 895–900 (1977).

Malik, A., Schumacher, H. R., Dinnella, J. E. & Clayburne, G. M. Clinical diagnostic criteria for gout: comparison with the gold standard of synovial fluid crystal analysis. J Clin. Rheumatol. 15, 22–24 (2009).

Taylor, W. J. et al. Performance of classification criteria for gout in early and established disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. (2014).

Neogi, T. et al. The Proposed New Preliminary Gout Classification Criteria. Annual Congress of American College of Rheumatology (2014).

McAdams, M. A. et al. Reliability and sensitivity of the self-report of physician-diagnosed gout in the campaign against cancer and heart disease and the atherosclerosis risk in the community cohorts. J. Rheumatol. 38, 135–141 (2011).

Harrold, L. R. et al. Validity of gout diagnoses in administrative data. Arthritis Rheum. 57, 103–108 (2007).

Singh, J. A., Hodges, J. S., Toscano, J. P. & Asch, S. M. Quality of care for gout in the US needs improvement. Arthritis Rheum. 57, 822–829 (2007).

Meier, C. R. & Jick, H. Omeprazole, other antiulcer drugs and newly diagnosed gout. Br. J. Clin Pharmacol 44, 175–178 (1997).

Taylor, W. J. et al. Toward a valid definition of gout flare: results of consensus exercises using Delphi methodology and cognitive mapping. Arthritis Rheum. 61, 535–543 (2009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made a substantial contribution to discussion of content and reviewed/edited the manuscript before submission. C.-F.K. researched data for and wrote the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

W.Z. declares that he has received personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo and is a member of guideline development groups for gout and osteoarthritis for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), EULAR and the British Society for Rheumatology (BSR). M.D. declares that he has received fees from ad hoc advisory activities related to gout and osteoarthritis (outside the submitted work) for Astrazeneca, Menarini, Nordic Biosciences, Novartis and Pfizer; he also declares that he is a clinical expert adviser on gout and osteoarthritis for NICE and a member of guideline development groups for gout for EULAR and BSR. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Tables

Supplementary Tables 1–5 (DOC 202 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kuo, CF., Grainge, M., Zhang, W. et al. Global epidemiology of gout: prevalence, incidence and risk factors. Nat Rev Rheumatol 11, 649–662 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2015.91

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2015.91

This article is cited by

-

Elevated serum IL-2 and Th17/Treg imbalance are associated with gout

Clinical and Experimental Medicine (2024)

-

Cardiovascular safety of using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for gout: a Danish nationwide case-crossover study

Rheumatology International (2024)

-

An update on the bioactivities and health benefits of two plant-derived lignans, phyllanthin and hypophyllanthin

Advances in Traditional Medicine (2024)

-

The Effects of Pharmacological Urate-Lowering Therapy on Cardiovascular Disease in Older Adults with Gout

Drugs & Aging (2024)

-

Effects of evodiamine on ROS/TXNIP/NLRP3 pathway against gouty arthritis

Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology (2024)