Key Points

-

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), the most common chronic liver disease, encompasses a histological spectrum ranging from simple steatosis to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), the latter of which has varying degrees of fibrosis. NASH can progress to cirrhosis and is projected to be the leading cause of liver transplantation by 2020. There is no approved therapy for NASH.

-

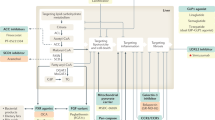

Several pharmacological strategies for NASH treatment, reflecting putative pathogenic mechanisms, are at the preclinical or early clinical stages of development, and include the modulation of nuclear transcription factors, reversal of lipotoxicity and oxidative stress, and modulation of cellular energy homeostasis and metabolism.

-

In parallel to these metabolic approaches, there is increasing evidence that numerous noxae that initiate liver disease converge to common, stereotyped patterns of injury, inflammation and fibrogenesis in NASH. Molecular mechanisms mediating cell injury and inflammation are also targeted by experimental therapies, including modulation of the inflammasome, chemokines and eicosanoids.

-

An important advance in our knowledge of liver diseases is the understanding that the most advanced stages of fibrosis (and even cirrhosis itself) are part of a dynamic process that may regress if the underlying fibrogenic stimuli are corrected. On this basis, several therapeutic strategies targeting key pathogenic mechanisms involved in fibrogenesis are being evaluated, including inhibitors of galectin 3, leukotrienes, caspases, Hedgehog signalling and lysyl oxidase-like 2 (LOXL2).

-

Collectively, these promising pharmacological strategies may become the armamentarium for an individualized treatment of NASH, targeting the predominant pathogenic mechanisms that operate in each patient and at each stage of disease.

-

Future randomized trials — of adequate power and duration, and with appropriate clinical outcomes — are needed to assess the long-term effectiveness and safety of each pharmacological option.

Abstract

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease — the most common chronic liver disease — encompasses a histological spectrum ranging from simple steatosis to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Over the next decade, NASH is projected to be the most common indication for liver transplantation. The absence of an effective pharmacological therapy for NASH is a major incentive for research into novel therapeutic approaches for this condition. The current focus areas for research include the modulation of nuclear transcription factors; agents that target lipotoxicity and oxidative stress; and the modulation of cellular energy homeostasis, metabolism and the inflammatory response. Strategies to enhance resolution of inflammation and fibrosis also show promise to reverse the advanced stages of liver disease.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Chalasani, N. et al. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Gastroenterological Association. Hepatology 55, 2005–2023 (2012).

Wong, R. J. et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the second leading etiology of liver disease among adults awaiting liver transplantation in the United States. Gastroenterology 148, 547–555 (2015).

Musso, G. et al. Association of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 11, e1001680 (2014).

Birkenfeld, A. L. & Shulman, G. I. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, hepatic insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes. Hepatology 59, 713–723 (2014).

Kirpich, I. A., Marsano, L. S. & McClain, C. J. Gut–liver axis, nutrition, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin. Biochem. 48, 923–930 (2015).

Musso, G., Cassader, M., Rosina, F. & Gambino, R. Impact of current treatments on liver disease, glucose metabolism and cardiovascular risk in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Diabetologia 55, 885–904 (2012).

Ding, L. et al. Coordinated actions of FXR and LXR in metabolism: from pathogenesis to pharmacological targets for type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 751859 (2014).

Roda, A. et al. Semisynthetic bile acid FXR and TGR5 agonists: physicochemical properties, pharmacokinetics, and metabolism in the rat. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 350, 56–68 (2014).

Zhang, Y., Castellani, L. W., Sinal, C. J., Gonzalez, F. J. & Edwards, P. A. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α) regulates triglyceride metabolism by activation of the nuclear receptor FXR. Genes Dev. 18, 157–169 (2004).

Min, H. K. et al. Increased hepatic synthesis and dysregulation of cholesterol metabolism is associated with the severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell. Metab. 15, 665–674 (2012). This study examines pathways involved in cholesterol metabolism that are altered in the liver of patients with NASH.

Kong, B. et al. Farnesoid X receptor deficiency induces nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in low-density lipoprotein receptor-knockout mice fed a high-fat diet. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 328, 116–122 (2009).

Fiorucci, S. et al. A farnesoid X receptor-small heterodimer partner regulatory cascade modulates tissue metalloproteinase inhibitor-1 and matrix metalloprotease expression in hepatic stellate cells and promotes resolution of liver fibrosis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 314, 584–595 (2005).

Ma, K., Saha, P. K., Chan, L. & Moore, D. D. Farnesoid X receptor is essential for normal glucose homeostasis. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 1102–1109 (2006).

Watanabe, M. et al. Bile acids lower triglyceride levels via a pathway involving FXR, SHP, and SREBP-1c. J. Clin. Invest. 113, 1408–1418 (2004).

Claudel, T. et al. Farnesoid X receptor agonists suppress hepatic apolipoprotein CIII expression. Gastroenterology 125, 544–555 (2003).

Neuschwander-Tetri, B. et al. Farnesoid X nuclear receptor ligand obeticholic acid for non-cirrhotic, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (FLINT): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 385, 956–965 (2015). To date, this study is the largest randomized trial with histological end points in NASH.

Xin, X. M. et al. GW4064, a farnesoid X receptor agonist, upregulates adipokine expression in preadipocytes and HepG2 cells. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 15727–15735 (2014).

Adams, A. C. et al. Fundamentals of FGF19 and FGF21 action in vitro and in vivo. PLoS ONE 7, e38438 (2012).

Wang, Y. D. et al. Farnesoid X receptor antagonizes NF-κB in hepatic inflammatory response. Hepatology 48, 1632–1643 (2008).

Pellicciari, R. et al. 6α-ethyl-chenodeoxycholic acid (6-ECDCA), a potent and selective FXR agonist endowed with anticholestatic activity. J. Med. Chem. 45, 3569–3572 (2002).

Musso, G. Obeticholic acid and resveratrol in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: all that is gold does not glitter, not all those who wander are lost. Hepatology 61, 2104–2106 (2015).

Li, G. et al. A tea catechin, epigallocatechin-3-gallate, is a unique modulator of the farnesoid X receptor. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 258, 268–274 (2012).

Carotti, A. et al. Beyond bile acids: targeting Farnesoid X Receptor (FXR) with natural and synthetic ligands. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 14, 2129–2142 (2014).

Banerjee, M., Robbins, D. & Chen, T. Targeting xenobiotic receptors PXR and CAR in human diseases. Drug Discov. Today 20, 618–628 (2014).

Sookoian, S. et al. The nuclear receptor PXR gene variants are associated with liver injury in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Pharmacogenet. Genom. 20, 1–8 (2010).

Zhou, J. et al. Hepatic fatty acid transporter Cd36 is a common target of LXR, PXR, and PPARγ in promoting steatosis. Gastroenterol. 134, 556–567 (2008).

Bitter, A. et al. Pregnane X receptor activation and silencing promote steatosis of human hepatic cells by distinct lipogenic mechanisms. Arch. Toxicol. 89, 2089–2103 (2015).

Moreau, A. et al. A novel pregnane X receptor and S14-mediated lipogenic pathway in human hepatocyte. Hepatology 49, 2068–2079 (2009).

Li, L. et al. SLC13A5 is a novel transcriptional target of the pregnane X receptor and sensitizes drug-induced steatosis in human liver. Mol. Pharmacol. 87, 674–682 (2015).

Hoekstra, M. et al. Activation of the nuclear receptor PXR decreases plasma LDL-cholesterol levels and induces hepatic steatosis in LDL receptor knockout mice. Mol. Pharm. 6, 182–189 (2009).

Miao, J., Fang, S., Bae, Y. & Kemper, J. K. Functional inhibitory cross-talk between constitutive androstane receptor and hepatic nuclear factor-4 in hepatic lipid/glucose metabolism is mediated by competition for binding to the DR1 motif and to the common coactivators, GRIP-1 and PGC-1α. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 14537–14546 (2006).

Valenti, L. et al. Increased expression and activity of the transcription factor FOXO1 in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Diabetes 57, 1355–1362 (2008).

Sun, M., Cui, W., Woody, S. K. & Staudinger, J. L. Pregnane X receptor modulates the inflammatory response in primary cultures of hepatocytes. Drug Metab. Dispos. 43, 335–343 (2015).

Wang, K., Damjanov, I. & Wan, Y. J. The protective role of pregnane X receptor in lipopolysaccharide/d-galactosamine-induced acute liver injury. Lab. Invest. 90, 257–265 (2010).

Kittayaruksakul, S. et al. Identification of three novel natural product compounds that activate PXR and CAR and inhibit inflammation. Pharm. Res. 30, 2199–2208 (2013).

Haughton, E. L. et al. Pregnane X receptor activators inhibit human hepatic stellate cell transdifferentiation in vitro. Gastroenterology 131, 194–209 (2006).

Marek, C. J. et al. Pregnenolone-16α-carbonitrile inhibits rodent liver fibrogenesis via PXR (pregnane X receptor)-dependent and PXR-independent mechanisms. Biochem. J. 387, 601–608 (2005).

Morere, P. et al. Information obtained by liver biopsy in 100 tuberculous patients. Sem. Hop. 51, 2095–2102 (1975).

Biswas, A., Pasquel, D., Tyagi, R. K. & Mani, S. Acetylation of pregnane X receptor protein determines selective function independent of ligand activation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 406, 371–376 (2011).

Souza-Mello, V. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors as targets to treat non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J. Hepatol. 7, 1012–1019 (2015).

Kim, H. et al. Liver-enriched transcription factor CREBH interacts with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α to regulate metabolic hormone FGF21. Endocrinology 155, 769–782 (2014).

Velkov, T. Interactions between human liver fatty acid binding protein and peroxisome proliferator activated receptor selective drugs. PPAR Res. 2013, 938401 (2013).

Qu, S. et al. PPARα mediates the hypolipidemic action of fibrates by antagonizing FoxO1. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 292, E421–E434 (2007).

Toyama, T. et al. PPARα ligands activate antioxidant enzymes and suppress hepatic fibrosis in rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 324, 697–704 (2004).

Mogilenko, D. A. et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α positively regulates complement C3 expression but inhibits tumor necrosis factor α-mediated activation of C3 gene in mammalian hepatic-derived cells. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 1726–1738 (2013).

Kleemann, R. et al. Fibrates down-regulate IL-1-stimulated C-reactive protein gene expression in hepatocytes by reducing nuclear p50-NFκB-C/EBP-β complex formation. Blood 101, 545–551 (2003).

Pawlak, M. et al. The transrepressive activity of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha is necessary and sufficient to prevent liver fibrosis in mice. Hepatology 60, 1593–1606 (2014). This study uncovers the transrepressive anti-fibrotic activity of PPARα in the liver.

Mansouri, R. M., Bauge, E., Staels, B. & Gervois, P. Systemic and distal repercussions of liver-specific peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α control of the acute-phase response. Endocrinology 149, 3215–3223 (2008).

Delerive, P. et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α negatively regulates the vascular inflammatory gene response by negative cross-talk with transcription factors NF-κB and AP-1. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 32048–32054 (1999).

Nagasawa, T. et al. Effects of bezafibrate, PPAR pan-agonist, and GW501516, PPARδ agonist, on development of steatohepatitis in mice fed a methionine- and choline-deficient diet. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 536, 182–191 (2006).

Ip, E., Farrell, G., Hall, P., Robertson, G. & Leclercq, I. Administration of the potent PPARα agonist, Wy-14,643, reverses nutritional fibrosis and steatohepatitis in mice. Hepatology 39, 1286–1296 (2004).

Bojic, L. A. et al.PPARδ activation attenuates hepatic steatosis in Ldlr−/− mice by enhanced fat oxidation, reduced lipogenesis, and improved insulin sensitivity. J. Lipid Res. 55, 1254–1266 (2014).

Wang, Y. X. et al. Peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor δ activates fat metabolism to prevent obesity. Cell 113, 159–170 (2003).

Lim, H. J. et al. PPARδ ligand L-165041 ameliorates Western diet-induced hepatic lipid accumulation and inflammation in LDLR−/− mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 622, 45–51 (2009).

Bays, H. E. et al. MBX-8025, a novel peroxisome proliferator receptor-δ agonist: lipid and other metabolic effects in dyslipidemic overweight patients treated with and without atorvastatin. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 96, 2889–2897 (2011).

Staels, B. et al. Hepatoprotective effects of the dual peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha/delta agonist, GFT505, in rodent models of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 58, 1941–1952 (2013). This study provides experimental evidence for the effectiveness of dual PPARα and PPARδ inhibition for the treatment of NASH.

Sanyal A. J., et al. The hepatic and extra-hepatic profile of resolution of steatohepatitis induced by GFT-505. Hepatology 62 (Suppl. 1), 1252A (2015).

Odegaard, J. J. et al. Macrophage-specific PPARγ controls alternative activation and improves insulin resistance. Nature 447, 1116–1120 (2007).

Zhao, C. et al. PPARγ agonists prevent TGFβ1/Smad3-signaling in human hepatic stellate cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 350, 385–391 (2006).

Hedrington, M. S. & Davis, S. N. Discontinued in 2013: diabetic drugs. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 23, 1703–1711 (2014).

Joshi, S. R. Saroglitazar for the treatment of dyslipidemia in diabetic patients. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 16, 597–606 (2015).

Shashank, R. et al. Saroglitazar in diabetic dyslipidemia: 1 year data. American Diabetes Association [online], (2015).

Mukul, R. et al. Saroglitazar shows therapeutic benefits in mouse model of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). American Diabetes Association [online], (2015).

Banshi, D. et al. To assess the effect of 4mg saroglitazar on patients of diabetes dyslipidemia with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease for 24 weeks at diabetes care centre. American Diabetes Association [online], (2015).

Puri, P. et al. A lipidomic analysis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 46, 1081–1090 (2007). This study provides evidence for the lipotoxicity of non-triglyceride lipid species in human NASH.

Gorden, D. L. et al. Increased diacylglycerols characterize hepatic lipid changes in progression of human nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; comparison to a murine model. PLoS ONE 6, e22775 (2011).

Musso, G., Gambino, R. & Cassader, M. Cholesterol metabolism and the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Prog. Lipid Res. 52, 175–191 (2013).

Bommer, G. T. & MacDougald, O. A. Regulation of lipid homeostasis by the bifunctional SREBF2-miR33a locus. Cell Metab. 13, 241–247 (2011).

Kang, Q. & Chen, A. Curcumin inhibits srebp-2 expression in activated hepatic stellate cells in vitro by reducing the activity of specificity protein-1. Endocrinology 150, 5384–5394 (2009).

Tomita, K. et al. Free cholesterol accumulation in hepatic stellate cells: mechanism of liver fibrosis aggravation in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Hepatology 59, 154–169 (2014). This study investigates mechanistic links connecting intracellular free-cholesterol accumulation to hepatic fibrosis in NASH.

Dávalos, A. et al. miR-33a/b contribute to the regulation of fatty acid metabolism and insulin signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 9232–9237 (2011).

Li, Z. J., Ou-Yang, P. H. & Han, X. P. Profibrotic effect of miR-33a with Akt activation in hepatic stellate cells. Cell Signal. 26, 141–148 (2014).

Liu, J. et al. Activation of mTORC1 disrupted LDL receptor pathway: a potential new mechanism for the progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 61, 8–19 (2011).

Musso, G., Cassader, M., Bo, S., De Michieli, F. & Gambino, R. Sterol regulatory element-binding factor 2 (SREBF-2) predicts 7-year NAFLD incidence and severity of liver disease and lipoprotein and glucose dysmetabolism. Diabetes 62, 1109–1120 (2013).

Baselga-Escudero, L. et al. Resveratrol and EGCG bind directly and distinctively to miR-33a and miR-122 and modulate divergently their levels in hepatic cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 882–892 (2014).

Baselga-Escudero, L. et al. Chronic supplementation of proanthocyanidins reduces postprandial lipemia and liver miR-33a and miR-122 levels in a dose-dependent manner in healthy rats. J. Nutr. Biochem. 25, 151–156 (2014).

Castro, B. M., Prieto, M. & Silva, L. C. Ceramide: a simple sphingolipid with unique biophysical properties. Prog. Lipid Res. 54, 53–67 (2014).

Cirera-Salinas, D. et al. Mir-33 regulates cell proliferation and cell cycle progression. Cell Cycle 11, 922–933 (2012).

Zhu, C. et al. MicroRNA-33a inhibits lung cancer cell proliferation and invasion by regulating the expression of β-catenin. Mol. Med. Rep. 11, 3647–3651 (2014).

Beckmann, N., Sharma, D., Gulbins, E., Becker, K. A. & Edelmann, B. Inhibition of acid sphingomyelinase by tricyclic antidepressants and analogons. Front. Physiol. 5, 331 (2014).

Holland, W. L. et al. Lipid-induced insulin resistance mediated by the proinflammatory receptor TLR4 requires saturated fatty acid-induced ceramide biosynthesis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 1858–1870 (2011). This study provides evidence that ceramide formation is necessary for saturated fatty acid-induced insulin resistance.

Kurek, K. et al. Inhibition of ceramide de novo synthesis reduces liver lipid accumulation in rats with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 34, 1074–1083 (2014).

Grammatikos, G. et al. Serum acid sphingomyelinase is upregulated in chronic hepatitis C infection and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1841, 1012–1020 (2014).

Cinar, R. et al. Hepatic cannabinoid-1 receptors mediate diet-induced insulin resistance by increasing de novo synthesis of long-chain ceramides. Hepatology 59, 143–153 (2014).

Fucho, R. et al. ASMase regulates autophagy and lysosomal membrane permeabilization and its inhibition prevents early stage non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Hepatol. 60, 1126–1134 (2014). This study provides evidence that acid sphingomyelinase inhibition improves experimental NASH.

Liu, Z. et al. Induction of ER stress-mediated apoptosis by ceramide via disruption of ER Ca2+ homeostasis in human adenoid cystic carcinoma cells. Cell Biosci. 4, 71 (2014).

Lee, S. Y. et al. Activation of sphingosine kinase 2 by endoplasmic reticulum stress ameliorates hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance in mice. Hepatology 62, 135–146 (2015).

Vandanmagsar, B. et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome instigates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Nat. Med. 17, 179–188 (2011). This report is the first demonstration that ceramide can activate the inflammasome, leading to caspase 1 cleavage.

Harvald, E. B., Olsen, A. S. & Færgeman, N. J. Autophagy in the light of sphingolipid metabolism. Apoptosis 20, 658–670 (2015).

Moles, A. et al. Acidic sphingomyelinase controls hepatic stellate cell activation and in vivo liver fibrogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 177, 1214–1224 (2010).

Czaja, M. J. A new mechanism of lipotoxicity: calcium channel blockers as a treatment for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis? Hepatology 62, 312–314 (2015).

Kornhuber, J., Tripal, P., Gulbins, E. & Muehlbacher, M. Functional inhibitors of acid sphingomyelinase (FIASMAs). Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 215, 169–186 (2013).

Kasumov, T. et al. Ceramide as a mediator of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and associated atherosclerosis. PLoS ONE 10, e0126910 (2015).

Bruce, C. R. et al. The sphingosine-1-phosphate analog FTY720 reduces muscle ceramide content and improves glucose tolerance in high fat-fed male mice. Endocrinology 154, 65–76 (2013).

Holland, W. L. et al. Receptor-mediated activation of ceramidase activity initiates the pleiotropic actions of adiponectin. Nat. Med. 17, 55–63 (2011). This is the first report to show that the anti-obesity and anti-inflammatory hormone adiponectin acts by stimulating ceramidase activity.

Liu, Y. et al. Metabolomic profiling in liver of adiponectin knockout mice uncovers lysophospholipid metabolism as an important target of adiponectin action. Biochem J. 469, 71–82 (2015).

Xia, J. et al. Targeted induction of ceramide degradation reveals roles for ceramides in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and glucose metabolism. American Diabetes Association [online], (2015).

Choi, C. S. et al. Suppression of diacylglycerol acyltransferase-2 (DGAT2), but not DGAT1, with antisense oligonucleotides reverses diet-induced hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 22678–22688 (2007). This is the first study to identify the different functions of DGAT1 and DGAT2 in the triglyceride synthetic pathway.

Sanyal, A. J. et al. Effect of pradigastat, a diacylglycerol acyltransferase 1 inhibitor, on liver fat content in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 62 (Suppl. 1), 1253A (2015).

Jornayvaz, F. R. et al. Hepatic insulin resistance in mice with hepatic overexpression of diacylglycerol acyltransferase 2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 5748–5752 (2011).

Harris, C. A. et al. DGAT enzymes are required for triacylglycerol synthesis and lipid droplets in adipocytes. J. Lipid Res. 52, 657–667 (2011).

Li, C. et al. Roles of Acyl-CoA: diacylglycerol acyltransferases 1 and 2 in triacylglycerol synthesis and secretion in primary hepatocytes. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 35, 1080–1091 (2015).

Toriumi, K. et al. Carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatic injury through formation of oxidized diacylglycerol and activation of the PKC/NF-κB pathway. Lab. Invest. 93, 218–229 (2013).

Takekoshi, S., Kitatani, K. & Yamamoto, Y. Roles of oxidized diacylglycerol for carbon tetrachloride-induced liver injury and fibrosis in mouse. Acta Histochem. Cytochem. 47, 185–194 (2014).

Lee, S. J. et al. PKCδ as a regulator for TGFβ1-induced α-SMA production in a murine nonalcoholic steatohepatitis model. PLoS ONE 8, e55979 (2013).

Ganji, S. H., Kukes, G. D., Lambrecht, N., Kashyap, M. L. & Kamanna, V. S. Therapeutic role of niacin in the prevention and regression of hepatic steatosis in rat model of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 306, G320–G327 (2014).

Ganji, S. H., Kashyap, M. L. & Kamanna, V. S. Niacin inhibits fat accumulation, oxidative stress, and inflammatory cytokine IL-8 in cultured hepatocytes: impact on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism 64, 982–990 (2015).

Cooper, D. L., Murrell, D. E., Roane, D. S. & Harirforoosh, S. Effects of formulation design on niacin therapeutics: mechanism of action, metabolism, and drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 490, 55–64 (2015).

Xing, X. et al. Mangiferin treatment inhibits hepatic expression of acyl-coenzyme A:diacylglycerol acyltransferase-2 in fructose-fed spontaneously hypertensive rats: a link to amelioration of fatty liver. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 280, 207–215 (2014).

Lee, K. et al. Discovery of indolyl acrylamide derivatives as human diacylglycerol acyltransferase-2 selective inhibitors. Org. Biomol. Chem. 11, 849–858 (2013).

Kim, M. O. et al. Discovery of a novel class of diacylglycerol acyltransferase 2 inhibitors with a 1H-pyrrolo[2,3-b]pyridine core. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 37, 1655–1660 (2014).

Chambel, S. S., Santos-Gonçalves, A. & Duarte, T. L. The dual role of Nrf2 in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: regulation of antioxidant defenses and hepatic lipid metabolism. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 597134 (2015).

Malloy, M. T. et al. Trafficking of the transcription factor Nrf2 to promyelocytic leukemia-nuclear bodies: implications for degradation of NRF2 in the nucleus. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 14569–14583 (2013).

Bhakkiyalakshmi, E., Sireesh, D., Rajaguru, P., Paulmurugan, R. & Ramkumar, K. M. The emerging role of redox-sensitive Nrf2–Keap1 pathway in diabetes. Pharmacol. Res. 91, 104–114 (2015).

Wang, C. et al. Nrf2 deletion causes 'benign' simple steatosis to develop into nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice fed a high-fat diet. Lipids Health Dis. 12, 165 (2013). This study provides evidence that NRF2 deletion is sufficient to promote the development of NASH from steatosis.

Meakin, P. J. et al. Susceptibility of Nrf2-null mice to steatohepatitis and cirrhosis upon consumption of a high-fat diet is associated with oxidative stress, perturbation of the unfolded protein response, and disturbance in the expression of metabolic enzymes but not with insulin resistance. Mol. Cell. Biol. 34, 3305–3320 (2014).

Collins, A. R. et al. Myeloid deletion of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 increases atherosclerosis and liver injury. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 32, 2839–2846 (2012).

Oh, C. J. et al. Sulforaphane attenuates hepatic fibrosis via NF-E2-related factor 2-mediated inhibition of transforming growth factor-β/Smad signaling. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 52, 671–682 (2012).

Shimozono, R. et al. Nrf2 activators attenuate the progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis-related fibrosis in a dietary rat model. Mol. Pharmacol. 84, 62–70 (2013).

Yu, Z. et al. Oltipraz upregulates the nuclear respiratory factor 2 α subunit (NRF2) antioxidant system and prevents insulin resistance and obesity induced by a high-fat diet in C57BL/6J mice. Diabetologia 54, 922–934 (2011); erratum 54, 989 (2011).

Cleasby, A. et al. Structure of the BTB domain of Keap1 and its interaction with the triterpenoid antagonist CDDO. PLoS ONE 9, e98896 (2014).

Jnoff, E. et al. Binding mode and structure-activity relationships around direct inhibitors of the Nrf2–Keap1 complex. Chem. Med. Chem. 9, 699–705 (2014).

Yuan, X. et al. Berberine ameliorates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by a global modulation of hepatic mRNA and lncRNA expression profiles. J. Transl. Med. 13, 24 (2015).

Li, L. et al. Resveratrol modulates autophagy and NF-κB activity in a murine model for treating non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Food Chem. Toxicol. 63, 166–173 (2014).

Park, E. J. & Pezzuto, J. M. The pharmacology of resveratrol in animals and humans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1852, 1071–1113 (2015).

Andrade, J. M. et al. Resveratrol attenuates hepatic steatosis in high-fat fed mice by decreasing lipogenesis and inflammation. Nutrition 30, 915–919 (2014).

Zhu, W. et al. Effects and mechanisms of resveratrol on the amelioration of oxidative stress and hepatic steatosis in KKAy mice. Nutr. Metab. (Lond). 11, 35 (2014).

Konings, E. et al. The effects of 30 days resveratrol supplementation on adipose tissue morphology and gene expression patterns in obese men. Int. J. Obes. (Lond). 38, 470–473 (2014).

Bagul, P. K. et al. Attenuation of insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and hepatic oxidative stress by resveratrol in fructose-fed rats. Pharmacol. Res. 66, 260–268 (2012).

Gomez-Zorita, S. et al. Resveratrol attenuates steatosis in obese Zucker rats by decreasing fatty acid availability and reducing oxidative stress. Br. J. Nutr. 107, 202–210 (2012).

Cho, S. J., Jung, U. J. & Choi, M. S. Differential effects of low-dose resveratrol on adiposity and hepatic steatosis in diet-induced obese mice. Br. J. Nutr. 108, 2166–2175 (2012).

Timmers, S. et al. Calorie restriction-like effects of 30 days of resveratrol supplementation on energy metabolism and metabolic profile in obese humans. Cell Metab. 14, 612–622 (2011). This is the first study assessing the metabolic effects of resveratrol in humans.

Faghihzadeh, F., Adibi, P., Rafiei, R. & Hekmatdoost, A. Resveratrol supplementation improves inflammatory biomarkers in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutr. Res. 34, 837–843 (2014).

Chen, S. et al. Resveratrol improves insulin resistance, glucose and lipid metabolism in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomized controlled trial. Dig. Liver Dis. 47, 226–232 (2015).

Poulsen, M. M. et al. High-dose resveratrol supplementation in obese men: an investigator-initiated, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of substrate metabolism, insulin sensitivity, and body composition. Diabetes 62, 1186–1195 (2013).

Chachay, V. S. et al. Resveratrol does not benefit patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 12, 2092–2103 (2014).

Smoliga, J. M. & Blanchard, O. Enhancing the delivery of resveratrol in humans: if low bioavailability is the problem, what is the solution? Molecules 19, 17154–17172 (2014).

Panchal, S. K., Poudyal, H. & Brown, L. Quercetin ameliorates cardiovascular, hepatic, and metabolic changes in diet-induced metabolic syndrome in rats. J. Nutr. 142, 1026–1032 (2012).

Ying, H. Z. et al. Dietary quercetin ameliorates nonalcoholic steatohepatitis induced by a high-fat diet in gerbils. Food Chem. Toxicol. 52, 53–60 (2013).

Surapaneni, K. M., Priya, V. V. & Mallika, J. Pioglitazone, quercetin and hydroxy citric acid effect on cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1) enzyme levels in experimentally induced non alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 18, 2736–2741 (2014).

Hoek-van den Hil, E. F. et al. Quercetin induces hepatic lipid omega-oxidation and lowers serum lipid levels in mice. PLoS ONE 8, e51588 (2013).

Guo, Y. & Bruno, R. S. Endogenous and exogenous mediators of quercetin bioavailability. J. Nutr. Biochem. 26, 201–210 (2015).

Jiang, S. et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 is regulated by the IRE1α-XBP1 branch of the unfolded protein response and counteracts endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced hepatic steatosis. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 29751–29765 (2014).

Li, Y. et al. Hepatic SIRT1 attenuates hepatic steatosis and controls energy balance in mice by inducing fibroblast growth factor 21. Gastroenterology 146, 539–549 (2014).

Wang, H., Qiang, L. & Farmer, S. R. Identification of a domain within peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma regulating expression of a group of genes containing fibroblast growth factor 21 that are selectively repressed by SIRT1 in adipocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 188–200 (2008).

Ogawa, Y. et al. bKlotho is required for metabolic activity of fibroblast growth factor 21. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 7432–7437 (2007).

Lee, D. V. et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 improves insulin sensitivity and synergizes with insulin in human adipose stem cell-derived (hASC) adipocytes. PLoS ONE 9, e111767 (2014).

Xu, J. et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 reverses hepatic steatosis, increases energy expenditure, and improves insulin sensitivity in diet-induced obese mice. Diabetes 58, 250–259 (2010).

Chau, M. D. et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 regulates energy metabolism by activating the AMPK–SIRT1–PGC-1α pathway. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 28, 12553–12558 (2010).

Liang, Q. et al. FGF21 maintains glucose homeostasis by mediating the cross talk between liver and brain during prolonged fasting. Diabetes 63, 4064–4075 (2014).

Douris, N. et al. Central fibroblast growth factor 21 browns white fat via sympathetic action in male mice. Endocrinology 156, 2470–2481 (2015).

Gaich, G. et al. The effects of LY2405319, an FGF21 analog, in obese human subjects with type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 18, 333–340 (2013).

Fisher, F. M. et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 limits lipotoxicity by promoting hepatic fatty acid activation in mice on methionine and choline-deficient diets. Gastroenterology 147, 1073–1083 (2014).

Fisher, F. M. et al. Obesity is a fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21)-resistant state. Diabetes 11, 2781–2789 (2010). This study introduces the concept of FGF21 resistance as a feature of obesity and diabetes.

Ye, X. et al. Long-lasting anti-diabetic efficacy of PEGylated FGF-21 and liraglutide in treatment of type 2 diabetic mice. Endocrine 49, 683–692 (2015).

Hecht, R. et al. Rationale-based engineering of a potent long-acting FGF21 analog for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. PLoS ONE 7, e49345 (2012).

Adams, A. C. et al. LY2405319, an engineered FGF21 variant, improves the metabolic status of diabetic monkeys. PLoS ONE 8, e65763 (2013).

Foltz, I. N. et al. Treating diabetes and obesity with an FGF21-mimetic antibody activating the βKlotho/FGFR1c receptor complex. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 162ra153 (2012).

Musso, G., Gambino, R. & Cassader, M. Emerging molecular targets for the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Annu. Rev. Med. 61, 375–392 (2010).

Castaño, D. et al. Cardiotrophin-1 eliminates hepatic steatosis in obese mice by mechanisms involving AMPK activation. J. Hepatol. 60, 1017–1025 (2014).

Hsu, W. H., Chen, T. H., Lee, B. H., Hsu, Y. W. & Pan, T. M. Monascin and ankaflavin act as natural AMPK activators with PPARα agonist activity to down-regulate nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in high-fat diet-fed C57BL/6 mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 64, 94–103 (2014).

Li, H. et al. AMPK activation prevents excess nutrient-induced hepatic lipid accumulation by inhibiting mTORC1 signaling and endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1842, 1844–1854 (2014).

Dong, J. et al. Quercetin reduces obesity-associated ATM infiltration and inflammation in mice: a mechanism including AMPKα1/SIRT1. J. Lipid Res. 55, 363–374 (2014).

Li, J. et al. Hepatoprotective effects of berberine on liver fibrosis via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. Life Sci. 98, 24–30 (2014).

Zhai, X. et al. Curcumin regulates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α expression by AMPK pathway in hepatic stellate cells in vitro. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 746, 56–62 (2015).

Kim, Y. C. & Guan, K. L. mTOR: a pharmacologic target for autophagy regulation. J. Clin. Invest. 125, 25–32 (2015).

Gwinn, D. M. et al. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol. Cell 30, 214–226 (2008).

Kim, K. et al. S6 kinase 2 deficiency enhances ketone body production and increases peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α activity in the liver. Hepatology 55, 1727–1737 (2012).

Peterson, T. R. et al. mTOR complex 1 regulates lipin 1 localization to control the SREBP pathway. Cell 146, 408–420 (2011).

Wang, C. et al. Inflammatory stress increases hepatic CD36 translational efficiency via activation of the mTOR signalling pathway. PLoS ONE 9, e103071 (2014).

Ma, K. L. et al. Activation of mTOR modulates SREBP-2 to induce foam cell formation through increased retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation. Cardiovasc. Res. 100, 450–460 (2013).

Sapp, V., Gaffney, L., EauClaire, S. F. & Matthews, R. P. Fructose leads to hepatic steatosis in zebrafish that is reversed by mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibition. Hepatology 60, 1581–1592 (2014). This study links diet-induced NASH to mTOR activation.

Jiang, H., Westerterp, M., Wang, C., Zhu, Y. & Ai, D. Macrophage mTORC1 disruption reduces inflammation and insulin resistance in obese mice. Diabetologia 57, 2393–2404 (2014).

Ai, D. et al. Disruption of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 in macrophages decreases chemokine gene expression and atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 114, 1576–1584 (2014).

Li, S. et al. Role of S6K1 in regulation of SREBP1c expression in the liver. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 412, 197–202 (2011).

Yuan, M. et al. Identification of Akt-independent regulation of hepatic lipogenesis by mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) complex 2. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 29579–29588 (2012).

Kumar, A. et al. Fat cell-specific ablation of rictor in mice impairs insulin-regulated fat cell and whole-body glucose and lipid metabolism. Diabetes 59, 1397–1406 (2010).

Lin, H. Y. et al. Effects of the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin on monocyte-secreted chemokines. BMC Immunol. 15, 37 (2014).

Inokuchi-Shimizu, S. et al. TAK1-mediated autophagy and fatty acid oxidation prevent hepatosteatosis and tumorigenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 3566–3578 (2014).

González-Rodríguez, A. et al. Impaired autophagic flux is associated with increased endoplasmic reticulum stress during the development of NAFLD. Cell Death Dis. 5, e1179 (2014).

Wang, L. et al. ALCAT1 controls mitochondrial etiology of fatty liver diseases, linking defective mitophagy to steatosis. Hepatology 61, 486–496 (2015).

Liu, K. et al. Impaired macrophage autophagy increases the immune response in obese mice by promoting proinflammatory macrophage polarization. Autophagy 11, 271–284 (2015).

Yin, J. et al. Rapamycin improves palmitate-induced ER stress/NFκB pathways associated with stimulating autophagy in adipocytes. Mediators Inflamm. 2015, 272313 (2015).

Sengupta, S., Peterson, T. R., Laplante, M., Oh, S. & Sabatini, D. M. mTORC1 controls fasting-induced ketogenesis and its modulation by ageing. Nature 468, 1100–1104 (2010).

Umemura, A. et al. Liver damage, inflammation, and enhanced tumorigenesis after persistent mTORC1 inhibition. Cell Metab. 20, 133–144 (2014).

Torricelli, C. et al. Phosphorylation-independent mTORC1 inhibition by the autophagy inducer Rottlerin. Cancer Lett. 360, 17–27 (2015).

Zhang, J. et al. 2-(3-Benzoylthioureido)-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrobenzo[b]thiophene-3-carboxylic acid ameliorates metabolic disorders in high-fat diet-fed mice. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 36, 483–496 (2015).

Ozaki, E., Campbell, M. & Doyle, S. L. Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome in chronic inflammatory diseases: current perspectives. J. Inflamm. Res. 8, 15–27 (2015).

Csak, T. et al. Both bone marrow-derived and non-bone marrow-derived cells contribute to AIM2 and NLRP3 inflammasome activation in a MyD88-dependent manner in dietary steatohepatitis. Liver Int. 34, 1402–1413 (2014).

Boaru, S. G., Borkham-Kamphorst, E., Tihaa, L., Haas, U. & Weiskirchen, R. Expression analysis of inflammasomes in experimental models of inflammatory and fibrotic liver disease. J. Inflamm. (Lond) 9, 49 (2012).

Wree, A. et al. NLRP3 inflammasome activation is required for fibrosis development in NAFLD. J. Mol. Med. (Berl) 92, 1069–1082 (2014). This study links inflammasome activation to the development of liver fibrosis in NASH.

Wree, A. et al. NLRP3 inflammasome activation results in hepatocyte pyroptosis, liver inflammation, and fibrosis in mice. Hepatology 59, 898–910 (2014).

Dixon, L. J., Flask, C. A., Papouchado, B. G., Feldstein, A. E. & Nagy, L. E. Caspase-1 as a central regulator of high fat diet-induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. PLoS ONE 8, e56100 (2013).

Ioannou, G. N. et al. Cholesterol-lowering drugs cause dissolution of cholesterol crystals and disperse Kupffer cell crown-like structures during resolution of NASH. J. Lipid Res. 56, 277–285 (2015).

Xu, C. et al. Xanthine oxidase in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and hyperuricemia: one stone hits two birds. J. Hepatol. 62, 1412–1419 (2015).

Miura, K. et al. Toll-like receptor 2 and palmitic acid cooperatively contribute to the development of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis through inflammasome activation in mice. Hepatology 57, 577–589 (2013).

Patton, A. et al. Small molecule inhibitors of inflammation delay the progression of high-fat diet-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in male C57BL6/J mice. American Diabetes Association [online], (2015).

Toki, Y. et al. Extracellular ATP induces P2X7 receptor activation in mouse Kupffer cells, leading to release of IL-1β, HMGB1, and PGE2, decreased MHC class I expression and necrotic cell death. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 458, 771–776 (2015).

Honda, H. et al. Isoliquiritigenin is a potent inhibitor of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and diet-induced adipose tissue inflammation. Leukoc. Biol. 96, 1087–1100 (2014).

Abderrazak, A. et al. Anti-inflammatory and anti-atherogenic effects of the inflammasome NLRP3 inhibitor arglabin in ApoE2.Ki mice fed a high fat diet. Circulation 131, 1061–1070 (2015).

Isakov, E., Weisman-Shomer, P. & Benhar, M. Suppression of the pro-inflammatory NLRP3/interleukin-1β pathway in macrophages by the thioredoxin reductase inhibitor auranofin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1840, 3153–3161 (2014).

Farooq, A. et al. Activation of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor downregulates inflammasome activity and liver inflammation via a β-arrestin-2 pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 307, G732–G740 (2014).

Ratziu, V. et al. A phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of GS-9450 in subjects with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 55, 419–428 (2012).

Henao-Mejia, J. et al. Inflammasome-mediated dysbiosis regulates progression of NAFLD and obesity. Nature 482, 179–185 (2012).

Bartneck, M., Warzecha, K. T. & Tacke, F. Therapeutic targeting of liver inflammation and fibrosis by nanomedicine. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 3, 364–376 (2014).

Kufareva, I., Salanga, C. L. & Handel, T. M. Chemokine and chemokine receptor structure and interactions: implications for therapeutic strategies. Immunol. Cell Biol. 93, 372–383 (2015).

Zhang, X. et al. Hepatic CXCR3 promotes non-alcoholic steatohepatitis through inflammation, lipid accumulation and autophagy deficiency. Gastroenterology 146, S922 (2014).

Miura, K., Yang, L., van Rooijen, N., Ohnishi, H. & Seki, E. Hepatic recruitment of macrophages promotes nonalcoholic steatohepatitis through CCR2. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 302, G1310–G1321 (2012).

Huang, W. et al. Depletion of liver Kupffer cells prevents the development of diet-induced hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance. Diabetes 59, 347–357 (2010).

Tosello-Trampont, A. C., Landes, S. G., Nguyen, V., Novobrantseva, T. I. & Hahn, Y. S. Kupffer cells trigger nonalcoholic steatohepatitis development in diet-induced mouse model through tumor necrosis factor-α production. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 40161–40172 (2012).

Wehr, A. et al. Pharmacological inhibition of the chemokine CXCL16 diminishes liver macrophage infiltration and steatohepatitis in chronic hepatic injury. PLoS ONE 9, e112327 (2014).

Karlmark, K. R. et al. Hepatic recruitment of the inflammatory Gr1+ monocyte subset upon liver injury promotes hepatic fibrosis. Hepatology 50, 261–274 (2009).

Rouault, C. et al. Roles of chemokine ligand-2 (CXCL2) and neutrophils in influencing endothelial cell function and inflammation of human adipose tissue. Endocrinology 154, 1069–1079 (2013).

Haukeland, J. W. et al. Systemic inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is characterized by elevated levels of CCL2. J. Hepatol. 44, 1167–1174 (2006).

Oh, D. Y. et al. Increased macrophage migration into adipose tissue in obese mice. Diabetes 61, 346–354 (2012).

Obstfeld, A. E. et al. C-C chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) regulates the hepatic recruitment of myeloid cells that promote obesity-induced hepatic steatosis. Diabetes 59, 916–925 (2010).

Kirk, E. A., Sagawa, Z. K., McDonald, T. O., O'Brien, K. D. & Heinecke, J. W. Monocyte chemoattractant protein deficiency fails to restrain macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue [corrected]. Diabetes 57, 1254–1261 (2008); erratum 57, 2552 (2008).

Baeck, C. et al. Pharmacological inhibition of the chemokine C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (monocyte chemoattractant protein 1) accelerates liver fibrosis regression by suppressing Ly-6C+ macrophage infiltration in mice. Hepatology 59, 1060–1072 (2014).

Seki, E. et al. CCR1 and CCR5 promote hepatic fibrosis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 1858–1870 (2009).

Chu, P. S. et al. C-C motif chemokine receptor 9 positive macrophages activate hepatic stellate cells and promote liver fibrosis in mice. Hepatology 58, 337–350 (2013).

Pérez-Martínez, L. et al. Maraviroc, a CCR5 antagonist, ameliorates the development of hepatic steatosis in a mouse model of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Antimicrob. Chemother. 69, 1903–1910 (2014).

Berres, M. L. et al. Antagonism of the chemokine Ccl5 ameliorates experimental liver fibrosis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 4129–4140 (2010).

Lefebvre, E. et al. Anti-fibrotic and anti-inflammatory activity of the dual CCR2 and CCR5 antagonist cenicriviroc in a mouse model of NASH. Hepatology 58, 221A–222A (2013). This study provides experimental evidence for the anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic activity of cenicriviroc.

Van Raemdonck, K., Van den Steen, P. E., Liekens, S., Van Damme, J. & Struyf, S. CXCR3 ligands in disease and therapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 26, 311–327 (2015).

Wehr, A. et al. Chemokine receptor CXCR6-dependent hepatic NK T cell accumulation promotes inflammation and liver fibrosis. J. Immunol. 190, 5226–5236 (2013).

Hammerich, L. et al. Chemokine receptor CCR6-dependent accumulation of γδ T cells in injured liver restricts hepatic inflammation and fibrosis. Hepatology 59, 630–642 (2014).

Karlmark, K. R. et al. The fractalkine receptor CX3CR1 protects against liver fibrosis by controlling differentiation and survival of infiltrating hepatic monocytes. Hepatology 52, 1769–1782 (2010).

Czaja, A. J. Hepatic inflammation and progressive liver fibrosis in chronic liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 2515–2532 (2014).

Bozinovski, S., Anthony, D. & Vlahos, R. Targeting pro-resolution pathways to combat chronic inflammation in COPD. J. Thorac. Dis. 6, 1548–1556 (2014).

Qin, C. et al. Cardioprotective potential of annexin-A1 mimetics in myocardial infarction. Pharmacol. Ther. 148, 47–65 (2015).

Vago, J. P. et al. Annexin A1 modulates natural and glucocorticoid-induced resolution of inflammation by enhancing neutrophil apoptosis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 92, 249–258 (2012).

Leoni, G. et al. Annexin A1, formyl peptide receptor, and NOX1 orchestrate epithelial repair. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 443–454 (2013).

Trentin, P. G. et al. Annexin A1-mimetic peptide controls the inflammatory and fibrotic effects of silica particles in mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 172, 3058–3071 (2015).

Locatelli, I. et al. Endogenous annexin A1 is a novel protective determinant in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Hepatology 60, 531–544 (2014).

Kosicka, A. et al. Attenuation of plasma annexin A1 in human obesity. FASEB J. 27, 368–378 (2013).

Akasheh, R. T., Pini, M., Pang, J. & Fantuzzi, G. Increased adiposity in annexin A1-deficient mice. PLoS ONE 8, e82608 (2013).

Dalli, J. et al. Proresolving and tissue-protective actions of annexin A1-based cleavage-resistant peptides are mediated by formyl peptide receptor 2/lipoxin A4 receptor. J. Immunol. 190, 6478–6487 (2013).

Kamaly, N. et al. Development and in vivo efficacy of targeted polymeric inflammation-resolving nanoparticles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 6506–6511 (2013).

Krishnamoorthy, S. et al. Resolvin D1 binds human phagocytes with evidence for proresolving receptors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 1660–1665 (2010).

Claria, J., Dalli, J., Yacoubian, S., Gao, F. & Serhan, C. N. Resolvin D1 and resolvin D2 govern local inflammatory tone in obese fat. J. Immunol. 189, 2597–2605 (2012).

Psychogios, N. et al. The human serum metabolome. PLoS ONE 6, e16957 (2011).

Hsieh, W. C. et al. Galectin-3 regulates hepatic progenitor cell expansion during liver injury. Gut 64, 312–321 (2015).

Kain, V. et al. Resolvin D1 activates the inflammation resolving response at splenic and ventricular site following myocardial infarction leading to improved ventricular function. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 84, 24–35 (2015).

Jung, T. W. et al. Resolvin D1 reduces ER stress-induced apoptosis and triglyceride accumulation through JNK pathway in HepG2 cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 391, 30–40 (2014).

Rius, B. et al. Resolvin D1 primes the resolution process initiated by calorie restriction in obesity-induced steatohepatitis. FASEB J. 28, 836–848 (2014).

Orr, S. K., Colas, R. A., Dalli, J., Chiang, N. & Serhan, C. N. Proresolving actions of a new resolvin D1 analog mimetic qualifies as an immunoresolvent. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 308, L904–L911 (2015).

Lacobini, C. et al. Accelerated lipid-induced atherogenesis in galectin-3-deficient mice: role of lipoxidation via receptor-mediated mechanisms. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 29, 831–836 (2009).

Pugliese, G., Iacobini, C., Pesce, C. M. & Menini, C. M. Galecin-3; an emerging all-out player in metabolic disorders and their complications. Glycobiology 25, 136–150 (2015).

Yang, R. Y., Hsu, D. K. & Liu, F. T. Expression of galectin-3 modulates T-cell growth and apoptosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 93, 6737–6742 (1996).

Elad-Sfadia, G., Haklai, R., Balan, E. & Kloog, Y. Galectin-3 augments K-Ras activation and triggers a Ras signal that attenuates ERK but not phosphoinositide 3-kinase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 34922–34930 (2004).

Oka, N. et al. Galectin-3 inhibits tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-induced apoptosis by activating Akt in human bladder carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 65, 7546–7553 (2005).

Park, J. W., Voss, P. G., Grabski, S., Wang, J. L. & Patterson, R. J. Association of galectin-1 and galectin-3 with Gemin4 in complexes containing the SMN protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 3595–3602 (2001).

Shimura, T. et al. Implication of galectin-3 in Wnt signaling. Cancer Res. 65, 3535–3537 (2005).

Lau, K. S. et al. Complex N-glycan number and degree of branching cooperate to regulate cell proliferation and differentiation. Cell 129, 123–134 (2007).

Fukumori, T. et al. CD29 and CD7 mediate galectin-3-induced type II T-cell apoptosis. Cancer Res. 63, 8302–8311 (2003).

Gao, X., Balan, V., Tai, G. & Raz, A. Galectin-3 induces cell migration via a calcium-sensitive MAPK/ERK1/2 pathway. Oncotarget 5, 2077–2084 (2014).

Volarevic, V. et al. Gal-3 regulates the capacity of dendritic cells to promote NKT-cell-induced liver injury. Eur. J. Immunol. 45, 531–543 (2015).

Iacobini, C. et al. Galectin-3 ablation protects mice from diet-induced NASH: a major scavenging role for galectin-3 in liver. J. Hepatol. 54, 975–983 (2011). This proof-of-concept study provides evidence that galectin 3 ablation is an effective strategy for treatment of NASH.

Henderson, N. C. et al. Galectin-3 regulates myofibroblast activation and hepatic fibrosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 5060–5065 (2006).

DePeralta, D. K. et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition attenuates liver fibrosis and development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 59, 1577–1590 (2014).

Maeda, N. et al. Stimulation of proliferation of rat hepatic stellate cells by galectin-1 and galectin-3 through different intracellular signaling pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 189–144 (2003).

Jeftic, I. et al. Galectin-3 ablation enhances liver steatosis, but attenuates inflammation and IL-33 dependent fibrosis in obesogenic mouse model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Mol. Med. 21, 453–465 (2015).

Traber, P. G. & Zomer, E. Therapy of experimental NASH and fibrosis with galectin inhibitors. PLoS ONE 8, e83481 (2013).

Traber, P. G. et al. Regression of fibrosis and reversal of cirrhosis in rats by galectin inhibitors in thioacetamide-induced liver disease. PLoS ONE 8, e75361 (2013). This study provides evidence of cirrhosis regression with pharmacological galectin 3 inhibition.

Harrison, S. A. et al. Early phase 1 clinical trial results of GR-MD-02, a galectin-3 inhibitor, in patients having non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) with advanced fibrosis. BVS [online], (2014).

Lacobini, C. et al. Advanced lipoxidation end-products mediate lipid-induced glomerular injury: role of receptor-mediated mechanisms. J. Pathol. 218, 360–369 (2009).

Pejnovic, N. et al. Galectin-3 deficiency accelerates high-fat diet induced obesity and amplifies inflammation in adipose tissue and pancreatic islets. Diabetes 62, 1932–1944 (2013).

Pang, J. et al. Increased adiposity, dysregulated glucose metabolism and systemic inflammation in galectin-3 KO mice. PLoS ONE 8, e57915 (2013).

Smedsrød, B., Melkko, J., Araki, N., Sano, H. & Horiuchi, S. Advanced glycation end products are eliminated by scavenger-receptor-mediated endocytosis in hepatic sinusoidal Kupffer and endothelial cells. Biochem. J. 322, 567–573 (1997).

Horrillo, R. et al. 5-lipoxygenase activating protein signals adipose tissue inflammation and lipid dysfunction in experimental obesity. J. Immunol. 184, 3978–3987 (2010).

Martinez-Clemente, M. et al. 5-lipoxygenase deficiency reduces hepatic inflammation and tumor necrosis factor α-induced hepatocyte damage in hyperlipidemia-prone ApoE-null mice. Hepatology 51, 817–827 (2010).

Moon, H. J., Finney, J., Ronnebaum, T. & Mure, M. Human lysyl oxidase-like 2. Bioorg. Chem. 57, 231–241 (2014).

Moon, H. J. et al. MCF-7 cells expressing nuclear associated lysyl oxidase-like 2 (LOXL2) exhibit an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) phenotype and are highly invasive in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 30000–30008 (2013).

Perepelyuk, M. et al. Hepatic stellate cells and portal fibroblasts are the major cellular sources of collagens and lysyl oxidases in normal liver and early after injury. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 304, G605–G614 (2013).

Barry-Hamilton, V. et al. Allosteric inhibition of lysyl oxidase-like-2 impedes the development of a pathologic microenvironment. Nat. Med. 16, 1009–1017 (2010).

Talal, A. H. et al. Simtuzumab, an antifibrotic monoclonal antibody against lylyl oxidase-like 2(LOXL2) enzyme, appears safe and well-tolerated in patients with liver disease of diverse etiology. J. Hepatol. 58, S532 (2013).

Rådmark, O., Werz, O., Steinhilber, D. & Samuelsson, B. 5-lipoxygenase, a key enzyme for leukotriene biosynthesis in health and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1851, 331–339 (2015).

Titos, E. et al. Inhibition of 5-lipoxygenase induces cell growth arrest and apoptosis in rat Kupffer cells: implications for liver fibrosis. FASEB J. 17, 1745–1747 (2003).

Matsuda, K & Iwak, Y. MN-001 (tipelukast), a novel, orally bioavailable drug, reduces fibrosis and inflammation and down-regulates TIMP-1, collagen Type 1 and LOXL2 mRNA overexpression in an advanced NASH (nonalcoholic steatohepatitis) model. Hepatology 60, 1283A (2014).

Hirsova, P. & Gores, G. J. Death receptor-mediated cell death and proinflammatory signaling in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1, 17–27 (2015).

Wieckowska, A. et al. In vivo assessment of liver cell apoptosis as a novel biomarker of disease severity in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 44, 27–33 (2006).

Kim, K. H., Chen, C. C., Monzon, R. I. & Lau, L. F. Matricellular protein CCN1 promotes regression of liver fibrosis through induction of cellular senescence in hepatic myofibroblasts. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33, 2078–2090 (2013).

Hatting, M. et al. Hepatocyte caspase-8 is an essential modulator of steatohepatitis in rodents. Hepatology 57, 2189–2201 (2013).

Barreyro, F. J. et al. The pan-caspase inhibitor Emricasan (IDN-6556) decreases liver injury and fibrosis in a murine model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Liver Int. 35, 953–966 (2015).

Spada, A. P. et al. Rapid and statistically significant reduction of markers of apoptosis and cell death in subjects with mild, moderate and severe hepatic impairment treated with a single dose of the pan caspase inhibitor, emricasan. Hepatology 60, 1277A (2014).

Xiao, Z., Ko, H. L., Goh, E. H., Wang, B. & Ren, E. C. hnRNP K suppresses apoptosis independent of p53 status by maintaining high levels of endogenous caspase inhibitors. Carcinogenesis 34, 1458–1467 (2013).

Hu, L., Lin, X., Lu, H., Chen, B. & Bai, Y. An overview of hedgehog signaling in fibrosis. Mol. Pharmacol. 87, 174–182 (2015).

Guy, C. D. et al. Treatment response in the PIVENS trial is associated with decreased Hedgehog pathway activity. Hepatology 61, 98–107 (2015).

Choi, S. S. et al. Activation of Rac1 promotes hedgehog-mediated acquisition of the myofibroblastic phenotype in rat and human hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology 52, 278–290 (2010).

Syn, W. K. et al. Accumulation of natural killer T cells in progressive nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 51, 1998–2007 (2010).

Philips, G. M. et al. Hedgehog signaling antagonist promotes regression of both liver fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in a murine model of primary liver cancer. PLoS ONE 6, e23943 (2011).

Hirsova, P., Ibrahim, S. H., Bronk, S. F., Yagita, H. & Gores, G. J. Vismodegib suppresses TRAIL-mediated liver injury in a mouse model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. PLoS ONE 8, e70599 (2013).

Kumar, V., Mundra, V. & Mahato, R. I. Nanomedicines of Hedgehog inhibitor and PPAR-γ agonist for treating liver fibrosis. Pharm. Res. 31, 1158–1169 (2014). This study provides evidence that vismodegib-encapsulating nanoparticles effectively reverse NASH and fibrosis.

Kisseleva, T. et al. Myofibroblasts revert to an inactive phenotype during regression of liver fibrosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 9448–9453 (2012).

Jun, J. I. & Lau L. F. Cellular senescence controls fibrosis in wound healing. Aging 2, 627–631 (2010).

Borkham-Kamphorst, E. et al. The anti-fibrotic effects of CCN1/CYR61 in primary portal myofibroblasts are mediated through induction of reactive oxygen species resulting in cellular senescence, apoptosis and attenuated TGF-β signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1843, 902–914 (2014).

Stiuso, P. et al. Serum oxidative stress markers and lipidomic profile to detect NASH patients responsive to an antioxidant treatment: a pilot study. Oxid Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 169216 (2014).

Torok, N. J., Dranoff, J. A., Schuppan, D. & Friedman, S. L. Strategies and endpoints of antifibrotic drug trials: summary and recommendations from the AASLD Emerging Trends Conference, Chicago, June 2014. Hepatology 62, 627–634 (2014).

Hardwick, R. N., Fisher, C. D., Canet, M. J., Lake, A. D. & Cherrington, N. J. Diversity in antioxidant response enzymes in progressive stages of human nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Drug Metab. Dispos. 38, 2293–2301 (2010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Related links

Supplementary information

Supplementary information S1 (table)

Mechanisms of action of natural antioxidants for the treatment of NAFLD (panel A) and main studies assessing the effect of resveratrol on markers of NAFLD (panel B). (PDF 245 kb)

Glossary

- Steatosis

-

Hepatic fatty infiltration in which the total fat content of the liver exceeds 5%.

- Steatohepatitis

-

A liver disease characterized by steatosis, inflammation, ballooning and degeneration of hepatocytes and varying degrees of fibrosis.

- Cirrhosis

-

A condition caused by long-standing liver injury from a variety of causes, which results in liver dysfunction, liver scarring with perturbed architecture and portal hypertension.

- Hepatic stellate cell

-

A liver-resident cell that is predominantly responsible for liver fibrosis.

- Methionine–choline-deficient diet

-

A dietary model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) that involves the administration of a diet with low levels of methionine and choline. Unlike other models of NASH, mice fed a methionine–choline-deficient diet do not develop insulin resistance.

- Nonparenchymal cells

-

Liver cells other than hepatocytes, including different populations of immune, inflammatory and pro-fibrogenic cells.

- M1 phenotype

-

One of two distinct functional states of polarized macrophage activation, the M1 macrophage subtype shows a 'pro-inflammatory' cytokine and chemokine profile.

- M2 phenotype

-

One of two distinct functional states of polarized macrophage activation, the M2 macrophage has an 'anti-inflammatory' cytokine and chemokine profile and is involved in immunosuppression and tissue repair. Importantly, in vitro, macrophages are capable of complete repolarization from M2 to M1 and can change again in response to fluctuations in the cytokine environment. The change in polarization is rapid and alters gene expression, protein and metabolite levels and microbicidal activity.

- Inflammasome

-

A multiprotein oligomer consisting of caspase 1, pyrin domain- and CARD-containing protein (PYCARD), a NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein and sometimes caspase 5 (also known as caspase 11). The exact composition of an inflammasome depends on which activator initiates inflammasome assembly. The inflammasome promotes the maturation of the inflammatory cytokines interleukin 1β (IL-1β) and IL-18 and is responsible for the activation of inflammatory processes in diverse cell lines.

- Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

-

A cellular process in which epithelial ductular-like cells disassemble the cell-to-cell attachments that tether them to adjacent cells and acquire a mesenchymal phenotype that allows them to migrate into the stroma, proliferate and synthesize extracellular matrix in response to various growth factors and cytokines.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Musso, G., Cassader, M. & Gambino, R. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: emerging molecular targets and therapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Drug Discov 15, 249–274 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd.2015.3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd.2015.3

This article is cited by

-

Transcriptional analysis of the expression and prognostic value of lipid droplet-localized proteins in hepatocellular carcinoma

BMC Cancer (2023)

-

The efficacy of L-carnitine in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and concomitant obesity

Lipids in Health and Disease (2023)

-

Restoration of lipid homeostasis between TG and PE by the LXRα-ATGL/EPT1 axis ameliorates hepatosteatosis

Cell Death & Disease (2023)

-

Valuable effects of lactobacillus and citicoline on steatohepatitis: role of Nrf2/HO-1 and gut microbiota

AMB Express (2023)

-

Bdh1 overexpression ameliorates hepatic injury by activation of Nrf2 in a MAFLD mouse model

Cell Death Discovery (2022)