Abstract

Many insects that rely on a single food source throughout their developmental cycle harbor beneficial microbes that provide nutrients absent from their restricted diet. Tsetse flies, the vectors of African trypanosomes, feed exclusively on blood and rely on one such intracellular microbe for nutritional provisioning and fecundity. As a result of co-evolution with hosts over millions of years, these mutualists have lost the ability to survive outside the sheltered environment of their host insect cells. We present the complete annotated genome of Wigglesworthia glossinidia brevipalpis, which is composed of one chromosome of 697,724 base pairs (bp) and one small plasmid, called pWig1, of 5,200 bp. Genes involved in the biosynthesis of vitamin metabolites, apparently essential for host nutrition and fecundity, have been retained. Unexpectedly, this obligate's genome bears hallmarks of both parasitic and free-living microbes, and the gene encoding the important regulatory protein DnaA is absent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Many arthropods with restricted diets, such as vertebrate blood, plant juice or wood, rely on symbiotic microorganisms to supply nutrients required for viability and fertility1. Among insects harboring such symbionts is the tsetse fly (Diptera: Glossinidae)—the vector of African trypanosomes, agents of deadly diseases in humans and animals in sub-Saharan Africa2. Tsetse flies harbor two symbiotic microorganisms in gut tissue: the obligate primary-symbiont Wigglesworthia glossinidia and the commensal secondary- symbiont Sodalis glossinidius. Whereas S. glossinidius may be found in various host tissue types, W. glossinidia is housed in differentiated host epithelial cells (bacteriocytes) that form the bacteriome organ2. The functional role of obligate symbionts in tsetses has been difficult to study, as their elimination results in retarded growth and a decrease in egg production and fecundity in the aposymbiotic host3,4. The ability to reproduce could be partially restored, however, when aposymbiotic flies received supplementation with B-complex vitamins, suggesting that the endosymbionts might have a metabolic role involving these compounds5.

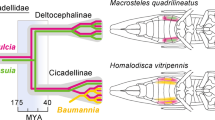

The phylogenetic characterization of W. glossinidia from distant tsetse species has shown that they form a distinct clade in the Enterobacteriaceae6 and display concordant evolution with their host species7. This finding implies that a tsetse ancestor was infected with a bacterium some 50–100 million years ago, and extant species of tsetse and associated W. glossinidia strains radiated without horizontal transfer of genetic material between species.

As a result of their intracellular lifestyle, the genomes of obligate symbionts have undergone massive reductions in comparison with their free-living relatives. The genome size of W. glossinidia has been estimated as 740–770 kilobases8 (kb), and that of Buchnera sp., the obligate symbiont of the pea aphid (Homoptera:Aphidoidea), as 640,681 bp9,10. Both genomes approach the size of the smallest genome reported thus far, that of Mycoplasma genitalium (580 kb)11. As a result of gene loss (and presumably loss of the associated functions), neither of these modern-day symbionts can live outside of its host insect. Here, we describe the general characteristics (Table 1) and main biological functions encoded by the W. glossinidia brevipalpis genome and draw comparisons to other intracellular microbes.

We analyzed the DNA sequence of W. glossinidia from Glossina brevipalpis (Austenina = fusca group) by the whole-genome random sequencing method. As the genome does not have a clear GC skewing, the adenine–thymine (AT)-rich region upstream of the gidA locus (where most oriC are located) was chosen as bp 1. Annotation revealed that the coding content of the genome is 89.1%. Similar to that of other intracellular bacteria12, the W. glossinidia genome has an exceptionally low average guanine-plus-cytosine (G+C) content of only 22%.

We determined the complete genetic map of W. glossinidia (Fig. 1). We identified 621 predicted coding sequences with an average length of 986 bp, and assigned biological roles to 522 (84%) of the coded proteins. A further 95 coding sequences (16%) matched hypothetical proteins of unknown function.

The predicted coding sequences were compared with a non-redundant protein database for assignment of putative functions. In addition, pWig1 encodes spermidine N1-acetyltransferase, three putative membrane proteins with similarities to a mechano-sensitive channel protein (yggB), a putative transmembrane protein of Salmonella typhimurium and a cation-transport inhibitor protein of Neisseria meningitidis (stomatin/Mec-2 family), respectively. Another of its predicted coding sequences products is homologous to TraT of the F incompatibility group plasmids. A small heat shock protein (ibp) is also encoded by the Buchnera plasmid.

In a previous study, where we hybridized DNA of W. pallidipes (a relative of W. brevipalpis studied here) to heterologous Escherichia coli gene arrays, we detected 457 orthologs, 197 of which were present in the genome of W. brevipalpis8. The additional homologous genes detected on the E. coli array may have been an artifact resulting from the extremely high AT content of the W. glossinidia genome. This may have caused the apparent variance between the two gene sets described by gene-array hybridization versus genome-wide sequence analysis. It is also possible that the composition of the W. pallidipes genome may be different from that of W. brevipalpis analyzed here.

The high A+T content of intracellular genomes may have resulted from loss of repair and recombination functions such as the SOS, base-excision and nucleotide-excision repair systems (uvrABC), all of which are absent from the W. glossinidia genome. Limited repair capability was also noted for the aphid symbiont Buchnera, which even lacks the recA gene10.

Notably, both sequence and hybridization data indicated that the gene encoding the DNA replication initiation protein, DnaA, is missing from the W. glossinidia genome—an observation unprecedented in eubacteria. Initiation of chromosome replication independent of oriC and DnaA has been reported under extreme physiological or genetic conditions13, when replication relies on the RecA and DnaG primase functions, both of which are present in W. glossinidia. The lack of robust, autonomous DNA replication machinery may reflect the dependency of W. glossinidia on host genome functions and may be one mechanism by which the host controls symbiont numbers.

Attempts to cultivate W. glossinidia in vitro in cell-free medium have not been successful, so we know little of its metabolic products. Based on its genome composition, however, W. glossinidia has the genomic capacity to generate pyruvate by means of glycolysis and gluconeogenesis. Although it lacks phosphofructokinase (pfkA), it generates transketolase (tktB) from the pentose phosphate cycle. The presence of the genes tpi, fda and fbp indicates that fructose-6-phosphate and glucose-6-phosphate may equilibrate, so that the pathway would result in the complete oxidation of hexose monophosphate to CO2. W. glossinidia appears to have a functional pantothenate–coenzyme A (CoA) biosynthetic pathway to produce acetyl-CoA from pantothenate. Its genome encodes a limited number of TCA-cycle enzymes for aerobic respiration. The organism has the succinate:ubiquinone oxidoreductase complex (complex II) to reduce ubiquinone (Q) in the membrane, although this reaction does not function as a proton pump. Cytochrome o is present and may act as an electron acceptor, but how charge separation across the membrane is generated is not clear. W. glossinidia also has an F0F1-type ATP synthase operon. Only a few genes associated with specific transporter functions are present in W. glossinidia: those encoding amino acid transporters (for glutamate/aspartate: gltL, gltJ, gltK; for serine: sdaC; for branched-chain amino acids: brnQ) and inorganic compounds (for potassium: trkA, trkD, trkH; for phosphate: pitA; for sodium proton antiport: nhaA) and multi-drug efflux proteins (mdl, mdlB, msbA), as well as several ABS transporters. No components of the phosphoenolpyruvate-carbohydrate phosphotransferase system are encoded by the genome.

Supplementation of the eukaryotic diet with metabolic products (such as amino acids in the case of Buchnera14,15) is thought to have a central functional role in the symbiotic relationships between obligate symbionts and their arthropod hosts. The restricted diet of tsetses (vertebrate blood) is vitamin deficient, and this, coupled with data from dietary supplementation experiments of antibiotic-fed symbiont-free flies, has caused tsetse symbionts to be assigned a putative role in B-vitamin metabolism3. Analysis of the predicted coding sequences of W. glossinidia further supports these nutritional observations. The W. glossinidia genome has retained 62 genes involved in the biosynthesis of cofactors, prosthetic groups and carriers, and has the potential to synthesize many cofactors including B vitamins (Fig. 2). The effects of energy-expensive life events such as pregnancy and trypanosome infections on the expression of these products are not known.

The sequential pathways are represented by arrows, each indicating one step catalyzed by the enzyme named. The end product of each reaction is boxed. The question markes indicate steps for which no genes were found in the W. glossinidia genome. The W. glossinidia genome encodes the potential to synthesize biotin, thiazole, lipoic acid, FAD (riboflavin, B2), folate, pantothenate, thiamine (B1), pyridoxine (B6), protoheme and nicotinamide.

Tsetses have a viviparous reproductive biology: an adult female produces one egg at a time that hatches and develops in utero. After maturation and sequential molting, a third-instar larva is deposited and pupates shortly thereafter. Nutrients and tsetse symbionts are transmitted to the intrauterine progeny through the mother's milk-gland secretions16,17. It is not known, however, whether whole bacteriocytes or W. glossinidia cells are transferred from a mother to her larva.

W. glossinidia has retained the machinery for the synthesis of a complete flagellar apparatus (Fig. 3). Although retention of genes associated with the flagellar operons suggests that they have a functional role, neither flagellum nor motility has been observed in W. glossinidia, though expression of a functional flagellum at certain life stages might facilitate the transmission of W. glossinidia to the intrauterine progeny by way of milk secretions. The W. glossinidia genome also does not seem to encode a secretion system mediating entry into the eukaryotic larval cells. The basal body of the flagella, which traverses from the cytoplasm to the outside of the cell, is structurally similar to the type III secretion apparatus associated with pathogenic organisms18. Hence, the flagella in W. glossinidia may also function as a type III secretion system that exports putative proteins to enable entry into the larval or pupal bacteriocytes, as in Yersinia enterocolitica19.

The pink boxes denote homologs present in the W. glossinidia genome and the green boxes show genes that are not present in W. glossinidia. W. glossinidia has retained genes encoding flagellar functions, including the basal body, hook, filament, filament cap regions and the integral membrane proteins required for motility functions, motA and motB. OM, outer membrane; P, periplasmic space; CM, cell membrane. Region III within the flagellar fli operon of E. coli and S. typhimurium is composed of two regions, IIIa and IIIb, with a disruption consisting of DNA unrelated to the flagellar system29. The disruption is ancient, having taken place approximately 150 million years ago30. The organization of the IIIa and IIIb region genes in W. glossinidia is continuous, however, suggesting that W. glossinidia predates the divergence of the two free-living bacteria.

We classified W. glossinidia coding sequences into functional categories and compared them to the profiles of two other intracellular genomes, the obligate Buchnera and the parasite Rickettsia prowazekii20 (Fig. 4). Although Buchnera and W. glossinidia share apparent functional and evolutionary similarities in regards to their symbiotic associations, their genetic blueprints are quite different. W. glossinidia shares only 69% of its coding sequences with Buchnera, and these represent the indispensable genes involved in transcription, translation and cellular functions. A greater proportion of the W. glossinidia genome is committed to the synthesis of products involved in cellular processes, cell structure, fatty-acid metabolism and, especially, biosynthesis of cofactors, whereas a greater percentage of the Buchnera genome encodes proteins involved in amino-acid biosynthesis. R. prowazekii, on the other hand, has little capability for biosynthesis of amino acids, cofactors or nucleic acids, but has significantly more genes encoding products with DNA metabolism and transport-related functions than either obligate symbiont. Indeed, whereas Buchnera and W. glossinidia have almost complete nucleotide biosynthetic pathways, parasitic microbes, including R. prowazekii, are often nucleotide scavengers. Free-living enterics and intracellular parasites (such as R. prowazekii) rely on their complex and flexible surface structures as protection from host defense mechanisms and environmental changes. In contrast, the obligate Buchnera, in its host-provisioned niche, has restricted membrane biogenesis capability10. Unlike Buchnera, the W. glossinidia genome encodes products integral to its Gram-negative cell-wall structure—enzymes involved in lipopolysaccharide and peptidoglycan biosynthesis. W. glossinidia may have retained membrane capabilities for protection from the host environment and defenses during transmission to the intrauterine larva.

Whereas the vast energy resources of eukaryotic hosts are exploited equally by parasitic and mutual symbionts, the beneficial obligate symbionts reciprocate by supplying products (such as amino acids or vitamins) that their hosts are unable to synthesize. One assumed outcome of the long-term intracellular association is that the obligate symbionts lose functions typically attributed to parasitism, such as host-cell invasion, an extensive membrane structure, DNA replication and DNA repair capabilities. In fact, the gene repertoire of Buchnera, which has been intracellularly associated with its aphid host for over 200 million years, lacks many genes associated with these functions. In contrast, the W. glossinidia genome displays the signatures of both mutualists and parasites. Although W. glossinidia can provide its tsetse host with metabolites such as vitamins and receive protection in specialized host cells, a significant portion of its small genome encodes components of its membrane structure and a full flagellar structure—both of which are presumed traits of free-living or parasitic microbes. Thus, either W. glossinidia represents a relatively recent symbiotic association, or its unique route of intrauterine transmission to the tsetse larva may have shaped its genome so that it retained functions associated with both obligate endosymbionts and parasitic microbes. The availability of this genomic information will now facilitate the development of experimental approaches to symbiosis to gain insight into the functional biology of the predicted traits in this unusual mutualistic association. Given the pivotal role of W. glossinidia in the fecundity of its host, these data can also lead to the development of new tsetse control strategies for managing the devastating diseases it transmits.

Methods

Insects, source of symbionts and DNA preparation.

The Glossina brevipalpis Newstead colony is maintained in the insectary at Yale University Laboratory of Epidemiology and Public Health. Tsetses are kept at 24°C with 55% humidity and are fed daily on defibrinated bovine blood (Crane Laboratories) using an artificial membrane system21. The bacteriome organs from about 2,000 adult tsetses were isolated by dissection. W. glossinidia cells were released by gentle homogenization of the tissue and were collected in buffer containing 10 mM Tris hydrochloride (pH 7.5) and 5 mM EDTA. The genomic DNA was prepared by a standard phenol/chloroform protocol22. The DNA was analyzed by PCR amplification using an S. glossinidius bacterium-specific primer set previously described23 to evaluate the level of DNA contamination (data not shown). No contamination with S. glossinidius was detected. Our previous analysis with G. brevipalpis had also indicated that the prevalence of S. glossinidius in this species is low17.

Genome sequence analysis.

Shotgun sequence libraries were prepared as described24. Briefly, genomic DNA fragments were hydrodynamically sheared using HydroShear (GeneMachines) to generate DNA fragments of 1–2 kb and 4–5 kb. The DNA fragments were made blunt-ended, phosphorylated, ligated with the dephosphorylated SmaI site of pUC18 vector and transformed into E. coli to obtain the libraries. For 1–2-kb fragments, PCR-based template DNA preparation was carried out according to the procedure described previously10. For 4–6-kb fragments, the plasmid DNAs were isolated for sequence analysis. Dye-terminator cycle sequence analysis was done using sequencing kits (Amersham-Pharmacia and ABI). All the trace data were analyzed with a PHRED/PHRAP software program (P. Green and B. Edwing, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington) for trimming of E. coli and vector sequences, base-calling and data assembly. Finishing processes including editing were performed on CONSED (D. Gordon, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington) and Sequencher (Gene Codes Corp). Gaps were closed and sequences analyzed by PCR followed by primer-walk sequence analysis, and ambiguities were re-analyzed by primer-walk. About 10-fold genome coverage was achieved by over 12,000 reads. The overall error probability was estimated by CONSED at less than 0.01%. The sizes of the predicted restriction endonuclease fragments coincided with the physical map.

Confirmation of the absence of dnaA.

To confirm the absence of dnaA from W. glossinidia genomes, we re-analyzed the sequence up to 4 kb upstream of the dnaN locus (because the dnaA gene is often located in this region in eubacteria). We also amplified the dnaA genes of E. coli and Buchnera by PCR and used them to detect their heterologous counterparts in W. glossinidia genomic Southern-blots. All of these experiments confirmed the absence of the dnaA gene in this genome (data not shown).

Informatics.

With respect to informatics, we used two strategies to identify putative CDSs. An initial set of ORFs, likely to encode proteins, was identified by the Glimmer2 program25. Both predicted ORFs and the intergenic regions were compared against a non-redundant protein database to confirm the putative CDSs. Combining these results, we identified and annotated the CDSs10,26. Frame shifts were detected and corrected where appropriate as described27. The isoelectric point for each protein was predicted using the 'iep' program in the EMBOSS analysis suite. Possible metabolic pathways were examined using the on-line service KEGG28.

URLs.

EMBOSS, http://www.hgmp.mrc.ac.uk/Software/EMBOSS/, http://wigglesworthia.gsc.riken.go.jp.

Accession numbers.

The accession numbers for the sequences are: AB063521–AB063522 for the W. glossinidia brevipalpis chromosome and AB063523 for the plasmid pWig-1.

References

Moran, N.A. & Baumann, P. Endosymbionts in animals. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3, 270–275 (2000).

Aksoy, S. Tsetse: a haven for microorganisms. Parasitol. Today 16, 114–119 (2000).

Nogge, G. Sterility in tsetse flies (Glossina morsitans Westwood) caused by loss of symbionts. Experientia 32, 995–996 (1976).

Hill, P.D.S. & Campbell, J.A. The production of symbiont-free Glossina morsitans and an associated loss of female fertility. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 67, 727–728 (1973).

Nogge, G. Significance of symbionts for the maintenance of an optional nutritional state for successful reproduction in hematophagous arthropods. Parasitology 82, 101–104 (1981).

Aksoy, S. Molecular analysis of the endosymbionts of tsetse flies: 16S rDNA locus and over-expression of a chaperonin. Insect Mol. Biol. 4, 23–29 (1995).

Chen, X., Song, L. & Aksoy, S. Concordant evolution of a symbiont with its host insect species: Molecular phylogeny of genus Glossina and its bacteriome-associated endosymbiont, Wigglesworthia glossinidia. J. Mol. Evol. 48, 49–58 (1999).

Akman, L. & Aksoy, S. A novel application of gene arrays: Escherichia coli array provides insight into the biology of the obligate endosymbiont of tsetse flies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 7546–7551 (2001).

Charles, H. & Ishikawa, H. Physical and genetic map of the genome of Buchnera, the primary endosymbiont of the pea aphid Acrythosiphon pisum. J. Mol. Evol. 48, 142–150 (1999).

Shigenobu, S., Watanabe, H., Hattori, M., Sakaki, Y. & Ishikawa, H. Genome sequence of the endocellular bacterial symbiont of aphids Buchnera sp. APS. Nature 407, 81–86 (2000).

Fraser, C. et al. The minimal gene complement of Mycoplasma genitalium. Science 270, 397–403 (1995).

Moran, N.A. Accelerated evolution and Muller's ratchet in endosymbiotic bacteria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 93, 2873–2878 (1996).

Asai, T. & Kogoma, T. The RecF pathway of homologous recombination can mediate the initiation of DNA damage-inducible replication of the Escherichia coli chromosome. J. Bacteriol. 176, 7113–7114 (1994).

Douglas, A. Nutritional interactions between Myzus persicae and its symbionts. in Aphid-plant Genotype Interactions (eds Campbell, R. & Eikenbary, R.) 319–327 (Elsevier Biomedical, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 1990).

Douglas, A.E. & Prosser, W.A. Synthesis of the essential amino acid tryptophan in the pea aphid (Acyrthosiphon pisum) symbiosis. J. Insect Physiol. 38, 565–568 (1992).

Ma, W.-C. & Denlinger, D.L. Secretory discharge and microflora of milk gland in tsetse flies. Nature 247, 301–303 (1974).

Cheng, Q. & Aksoy, S. Tissue tropism, transmission and expression of foreign genes in vivo in midgut symbionts of tsetse flies. Insect Mol. Biol. 8, 125–132 (1999).

Kubori, T. et al. Supramolecular structure of the Salmonella typhimurium type III protein secretion system. Science 280, 602–605 (1998).

Young, G.M., Schmiel, D.H. & Miller, V.L. A new pathway for the secretion of virulence factors by bacteria: the flagellar export apparatus functions as a protein-secretion system. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 6456–6461 (1999).

Andersson, S.G. et al. The genome sequence of Rickettsia prowazekii and the origin of mitochondria. Nature 396, 133–140 (1998).

Moloo, S.K. An artificial feeding technique for Glossina. Parasitology 63, 507–512 (1971).

Sambrook, J. & Russell, D.W. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual (Cold Spring Harbor Press, Cold Spring Harbor, New York, 2001).

O'Neill, S.L., Gooding, R.H. & Aksoy, S. Phylogenetically distant symbiotic microorganisms reside in Glossina midgut and ovary tissues. Med. Vet. Entomol. 7, 377–383 (1993).

Fleischmann, R.D. et al. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science 269, 496–512 (1995).

Delcher, A.L., Harmon, D., Kasif, S., White, O. & Salzberg, S.L. Improved microbial gene identification with GLIMMER. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 4636–4641 (1999).

Watanabe, H., Mori, H., Itoh, T. & Gojobori, T. Genome plasticity as a paradigm of eubacteria evolution. J. Mol. Evol. 44, S57–S64 (1997).

Tomb, J.F. et al. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 388, 539–547 (1997).

Ogata, H. et al. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 29–34 (1999).

Kawagishi, I., Muller, V., Williams, A.W., Irikura, V.M. & Macnab, R.M. Subdivision of flagellar region III of the Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium chromosomes and identification of two additional flagellar genes. J. Gen. Microbiol. 138, 1051–1065 (1992).

Ochman, H. & Groisman, E.A. The origin and evolution of species differences in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. EXS 69, 479–493 (1994).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank K. Furuya and C. Yoshino for their technical assistance; I. Kasumba for maintenance of the tsetse colonies; and the members of the Seibersdorf Agricultural Research laboratory, Austria, for their assistance with tsetse pupae. We also thank R.V.M. Rio, D. Nayduch and P. Strickler for their comments and editorial suggestions. This work was supported in part by the Research for the Future Program from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science to M.H., the US National Institutes of Health/Nation Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to S.A. and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Area (C) “Genome Science” from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan to H.W.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Akman, L., Yamashita, A., Watanabe, H. et al. Genome sequence of the endocellular obligate symbiont of tsetse flies, Wigglesworthia glossinidia. Nat Genet 32, 402–407 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/ng986

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng986

This article is cited by

-

Symbioses shape feeding niches and diversification across insects

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2023)

-

Bacterial symbionts support larval sap feeding and adult folivory in (semi-)aquatic reed beetles

Nature Communications (2020)

-

Bacterial endosymbionts of Placobdella (Annelida: Hirudinea: Glossiphoniidae): phylogeny, genetic distance, and vertical transmission

Hydrobiologia (2020)

-

Genome expansion of an obligate parthenogenesis-associated Wolbachia poses an exception to the symbiont reduction model

BMC Genomics (2019)

-

Molecular characterization, ultrastructure, and transovarial transmission of Tremblaya phenacola in six mealybugs of the Phenacoccinae subfamily (Insecta, Hemiptera, Coccomorpha)

Protoplasma (2019)