Abstract

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is the most common soft-tissue sarcoma in childhood. Here we studied 60 RMSs using whole-exome/-transcriptome sequencing, copy number (CN) and DNA methylome analyses to unravel the genetic/epigenetic basis of RMS. On the basis of methylation patterns, RMS is clustered into four distinct subtypes, which exhibits remarkable correlation with mutation/CN profiles, histological phenotypes and clinical behaviours. A1 and A2 subtypes, especially A1, largely correspond to alveolar histology with frequent PAX3/7 fusions and alterations in cell cycle regulators. In contrast, mostly showing embryonal histology, both E1 and E2 subtypes are characterized by high frequency of CN alterations and/or allelic imbalances, FGFR4/RAS/AKT pathway mutations and PTEN mutations/methylation and in E2, also by p53 inactivation. Despite the better prognosis of embryonal RMS, patients in the E2 are likely to have a poor prognosis. Our results highlight the close relationships of the methylation status and gene mutations with the biological behaviour in RMS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS), a highly aggressive soft-tissue sarcoma, typically affects children, and it is classified into two major subtypes having alveolar (ARMS) and embryonal (ERMS) histologies1,2. ARMS usually carries specific chromosomal translocations that result in PAX3– or PAX7–FOXO1 fusion genes, whereas ERMS commonly harbours loss of heterozygosity at 11p15.5 and gains of chromosomes 2, 8, and 12 in varying combinations3,4. Despite aggressive multimodal therapies, the prognosis of high-risk RMS patients has not been substantially improved, with a 5-year overall survival rate being <20–30%5, which prompts a need for new therapeutic strategies targeting molecular pathways that are relevant to the pathogenesis of RMS. In this point of view, recent sequencing studies have revealed a number of recurrent mutational targets of RMS, including multiple components of the FGFR4/RAS/AKT pathway, FBXW7, CTNNB1 and BCOR6,7. However, the relatively low number of mutations in RMS (12.3/tumor sample7) suggests the involvement of other mechanisms, such as epigenetic alterations, which have not been disclosed in the previous studies6,7,8. To address these issues, we conducted an integrated molecular study in which a cohort of 60 RMSs cases was investigated for somatic mutations, CN alterations, and DNA methylomes using whole-exome/targeted deep sequencing, Single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array-based CN analysis, and Infinium 450 K arrays, respectively. RNA sequencing was also performed for the selected tumours for which high-quality RNA was available (that is, RNA integrity number >6.0). Here we identify novel methylation clusters that exhibit distinct genetic abnormalities, histological subtypes and clinical behaviours, suggesting that aberrant DNA methylation along with genetic alterations is likely to play key roles in the pathogenesis of RMS.

Results

Sequencing and CN analyses of RMS

We first sequenced the exome of 16 paired tumours/normal samples of which 3 were also analysed for relapsed (n=2) and metastatic (n=1) samples (Supplementary Data 1). The mean coverage was 123 × , with which 88% of the target exome sequences were analysed at a depth of more than 20 × (Supplementary Fig. 1). Among 690-candidate somatic changes detected by our pipeline called Genomon (http://genomon.hgc.jp/exome/en/index.html), 604 in 531 genes (88%) were validated by deep sequencing (Supplementary Data 2). The mean numbers of mutation in primary, metastatic, and relapsed tumours were 24.0, 43.3 and 42.0, respectively. Thus, the mutation rate was slightly higher in relapsed/metastatic tumours than in primary tumours, although not statistically significant (primary versus metastasis, t-test P=0.20 and primary versus relapsed, P=0.13; Supplementary Fig. 2). An excessively high number of somatic mutations was present in one case (RMS_001) in which an MBD4 gene mutation was implicated in defective DNA repair9 (Supplementary Fig. 2). As observed in other cancers, mutations were predominated by C>T/G>A transitions compared with other transitions or transversions10 (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Among the 531 mutated genes, only 18 were recurrently mutated (Table 1), which not only included known mutational targets in RMS, such as TP53, BCOR, KRAS and other genes in the FGFR4/RAS/AKT pathway, but also involved in previously unreported genes, including ROBO1 and additional FGFR4/RAS/AKT pathway genes6,7,8,11, such as GAB1 and PTEN (Table 1). Thus, to validate the initial observation in the discovery samples and investigate the impact of these mutations on the pathogenesis and clinical outcomes of RMS, we performed follow-up deep sequencing for 14 putative driver genes in the entire cohort of 60 RMS cases including the 16 discovery cases (Supplementary Data 3). Overall, 56 mutations were found in the 14 genes (Table 2, Supplementary Data 4, Supplementary Fig. 4). The most frequently mutated genes were TP53 (9/60; 15.0%) and FGFR4/RAS/AKT pathway genes (24/60; 40%), which were predominantly detected in ERMS tumours7 (Fig. 1, Table 2). Among FGFR4/RAS/AKT pathway mutations, RAS pathway genes were mutated in 15 cases, in which all mutations in NRAS/KRAS/HRAS (n=10) and PTPN11 (n=2) occurred in hot-spot amino acids involved in gene activation, whereas three of four NF1 mutations were frameshift indels resulting in premature truncation of the protein. Five of six FGFR4 mutations affected highly conserved amino acids within the kinase domain of which four were previously reported activating mutations11, N535K and V550L. Additional four mutations involved PIK3CA, which have previously been reported in other cancers, are thought to be activating in nature12,13,14. Other commonly mutated genes were BCOR and ARID1A. All BCOR mutations and four of six ARID1A mutations were frameshift or nonsense mutations, suggesting the importance of inactivation of these genes in the pathogenesis of RMS.

The FGFR4/RAS/AKT pathway (a), cell cycle, and p53 signalling (b) are frequently altered. Genes with genetic alterations are coloured in light orange. The types of alterations and their frequency in the population are indicated on the right side of each gene. The percentages of cases with alterations including copy-number alterations and/or gene mutations detected in embryonal and alveolar subgroups are separately indicated on the left side of each gene. PTEN methylation is also indicated below the gene name and coloured in orange.

A number of genes and pathways were also recurrently affected by CN alterations and thought to be implicated in deregulated FGFR4/RAS/AKT signalling (focal amplification of FRS2 at 12q15; 12%) and cell cycle regulation (focal amplification of MYCN at 2p24.3, loss of CDKN2A/B at 9p21, TP53 at 17p13.2, and MDM2 at 12q15; Figs 1 and 2, Supplementary Fig. 5). Other genes displaying significant CN alterations included ALK (2p23.2) and STAT6 (12q13.3) (Supplementary Data 5 and 6). As previously reported, the ARMS-related fusion genes PAX3/7 (n=6) and FOXO1 (n=6) were frequently accompanied by local amplifications15,16.

(a) Statistically significant CN gains and losses detected by the GISTIC algorithm are shown in the left and right boxes, respectively. For each q-value peak, the putative gene targets are listed. A dashed line represents the centromere of each chromosome. Red and blue lines indicate the q-value for gains and losses, respectively. (b–h) Heatmaps of significant CN alterations are shown for gene targets at 1p36.13 (b), 2p24.3 (c), 2q36.1 (d), 12q15 (e), 13q14.1 (f), 9p21.1 (g) and 17p13.1 (h).

Transcriptome analysis of RMS

Fusion transcripts were investigated by RNA sequencing in eight cases of RMS, including five ERMS and three ARMS cases (Supplementary Data 1). In total, we identified 22 fusion transcripts, of which three were predicted to be in-frame, whereas the remaining 19 were out-of-frame fusions. Expression of fusion transcripts was confirmed by reverse transcription-PCR (RT–PCR) for 2 in-frame and 10 out-of-frame fusions (Supplementary Data 7), but no recurrent fusions were identified, except for the PAX3–FOXO1 fusion found in two cases of ARMS. The NSD1–ZNF346 fusion that was previously identified in an ERMS cell line6, was found in a case of ERMS. However, the NSD1–ZNF346 fusion detected in our study was out-of-frame and thus functional significance of this fusion transcript is still elusive.

Novel clusters identified by DNA methylation analysis

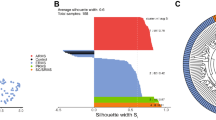

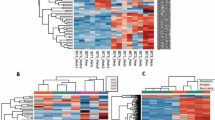

To further explore the molecular basis of RMS, we investigated genome-wide DNA methylation in 53 RMS tumours using Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip (Illumina). DNA methylation profiling based on unsupervised hierarchical clustering identified four unique clusters having distinct methylation signatures (Fig. 3a), and the microarray data were validated by bisulfite sequencing for selected probes (n=160; Supplementary Fig. 6). Remarkably, we found that these clusters correlated with histological subtypes, genetic abnormalities and clinical outcomes. Two clusters, E1 and E2, were composed almost exclusively of ERMS (95.5%; Fig. 3a), whereas all cases of ARMS were grouped into the two remaining clusters A1 and A2 (Fig. 3a). Accordingly, all tumours positive for PAX3–FOXO1 or PAX7–FOXO1 fusions were grouped into the A1/A2 clusters, although the separation between A1 and A2 did not coincide with the presence or absence of fusions (Fig. 3a). In our analysis, 29 genes were significantly hypermethylated in the E1/E2 clusters compared with the A1/A2 clusters. On the other hand, only 10 genes were significantly hypermethylated in the A1/A2 clusters compared with those in the E1/E2 cluster (Fig. 3b; Supplementary Fig. 7; Supplementary Data 8). Among these, the largest extent of promoter methylation was observed in PTEN in the clusters E1/E2 and GATA4 in the clusters A1/A2. Of note, we found an extremely high frequency of PTEN hypermethylation in E/E2 tumours (20 of 22; 90.9%), whereas only two of 28 (7.1%) in A1/A2 tumours showed PTEN hypermethylation (Fig. 3c). Subsequent quantitative RT–PCR analysis revealed that PTEN hypermethylation was significantly associated with the absence of PTEN expression, suggesting that epigenetic silencing of PTEN is a representative mechanism of E1/E2 tumours (P=0.045; Supplementary Fig. 8). GATA4 encodes a member of the GATA family of transcription factors17,18 and has been shown to be methylated in a subset of RMS cases19. However, because GATA4 expression is limited to the heart, testis and ovary, significance of methylation in RMS pathology is still unclear. We also found 23 genes significantly hypermethylated in E2 compared with E1 and 25 genes in A1 to A2 (Supplementary Fig. 9, Supplementary Data 9 and 10). Although these findings should be validated in independent samples, methylation of these genes could be potentially used for discriminating these subtypes.

(a) The heatmap shows the DNA methylation profiles of 53 rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) tumours based on unsupervised hierarchical clustering. Tumours were hierarchically clustered into four subgroups: E1, E2, A1 and A2. Clusters E1 and E2 were composed almost exclusively of embryonal RMS (95.5%), whereas all alveolar RMS were classified into clusters A1/A2. Red, high methylation; blue, low methylation. (b) Volcano plot comparing the number of significantly hypermethylated probes between clusters E1/E2 and A1/A2. Significantly hypermethylated probes showing >2-fold change are coloured in orange (P<1.0 × 10−8, Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test). Red dots represent significantly hypermethylated probes in the promoter regions of PTEN in cluster E. (c) Difference in PTEN methylation intensities between clusters E1/E2 and A1/A2. Significantly higher methylation intensities were observed in cluster E1/E2 than in cluster A1/A2. The P-value was calculated using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. β-values represent significantly hypermethylated eight promoter-associated probes (red dots in the Volcano plot) of PTEN. For the box and whisker plots, the bottom and top of the box are the first and third quartiles, the line inside the box is the median and the whiskers extend up to 1.5 times the interquartile range.

Characteristics of the methylation subgroups in RMS

To obtain a better understanding of DNA methylation in each subgroup, we further performed Ingenuity pathway analysis (http://www.ingenuity.com/) using probe lists of E1/E2 versus A1/A2, E1 versus E2 and A1 versus A2 (Supplementary Data 8–10). However, relevant cancer-associated pathways in the pathogenesis of RMS were not detected in the A1/A2 and E1/E2 subgroups (Supplementary Data 11 and 12). A functional annotation named ‘abnormal morphology of muscle,’ containing DYSF, ELN, OTX2 and TH, was detected as a significantly hypermethylated component in A1 compared with A2 (P=6.2 × 10−4; Supplementary Data 13–16). In addition, the promoter of P4HTM, the family of prolyl 4-hydroxylases, was significantly hypermethylated in E2 compared with E1 (P=0.035; Supplementary Fig. 9). Intriguingly, P4HTM hypermethylation was also reported in a previous study regarding DNA promoter methylation in 10 RMS tumours19. However, the biological significance of these genes in the pathogenesis of RMS is still unclear.

Next, we analysed the genetic and clinical characteristics of each methylation subgroup. E1 tumours showed a lower mutation rate (mean, 20.0/sample) than E2 tumours (mean, 45.0/sample), although not statistically significant (P=0.084). Compared with the A1/A2 clusters, the E1/E2 clusters were characterized by high frequencies of multiple chromosomal CN changes including gains of chromosomes 2, 8 or 12 (P=5.2 × 10−4). In addition, the mutation frequency of the FGFR4/RAS/AKT pathway was much higher in the E1/E2 clusters than in the A1/A2 clusters (P=4.6 × 10−4), and these mutations were predominantly observed in the E2 cluster (54.5% in E1 and 81.8% in E2 versus 17.9% in A1/A2; Fig. 4; Table 2). Among the FGFR4/RAS/AKT pathway mutations, mutations in FGFR4, PTPTN11 and PIK3CA frequently occurred in E2 compared with E1 (P=1.0 × 10−3). Furthermore, E2 tumours had significantly frequent TP53 mutations (45.5%) compared with E1 tumours (0%; P=0.035). In contrast, mutations and CN alterations affecting cell cycle regulators, such as MYCN, CDK4 and CDKN2A/B, except for MDM2, were particularly enriched in the A1/A2 clusters compared with the E1/E2 clusters (P=0.016), suggesting that these genes may have driver roles in A1/A2 tumours.

(a) Integrated view of DNA methylation clusters combined with histology, outcome, fusion status, gene alterations and copy-number changes. The horizontal axis represents each tumor. ARMS, alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma; ERMS, embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma; NOS, not otherwise specified; Mut, mutation; Met, methylation; CNA, copy-number alteration; Hetero., heterozygous; Com. Hetero., compound heterozygous mutation; CN, copy number; LOH, loss of heterozygosity; N, NRAS; K, KRAS; H, HRAS; P, detected in primary sample alone; R, Detected in relapse sample alone; F, PAX3–FOXO1 fusion-positive ERMS. (b) Kaplan–Meier curves of overall survival for each DNA methylation cluster. The P-value of the log-rank test is shown.

Finally, patients in the E2 cluster displayed significantly worse overall survival than those in the E1 cluster, regardless of stage, age and the site of tumour involvement (P=0.045; Fig. 4b). In addition, among commonly mutated genes and pathways, only TP53 mutations but not FGFR4/RAS/AKT pathway mutations (including FGFR4, PTPN11, PIK3CA and PTEN mutations) significantly affected the overall survival of E1/E2 patients (P=2.9 × 10−3). However, the impact of the E1/E2 classification on overall survival was more prominent than that of the TP53 mutations (Supplementary Fig. 10). These results suggest that the methylation status that defines the E1/E2 clusters might be a predictor of overall survival, independent of gene mutations.

Discussion

Our sequencing screen identified both previously well-recognized gene mutations including FGFR4/RAS/AKT pathway mutations and novel recurrently mutated genes, such as PTEN, GAB1 and ROBO. Most FGFR4/RAS/AKT pathway alterations, excluding GAB1, were predominantly found in ERMS (Fig. 1), suggesting that deregulated FGFR4/RAS/AKT signalling plays an important role in the pathogenesis of ERMS. Because the PTEN missense mutation affecting G129 has been reported in several cancers20,21 and is thought to abrogate most PTEN activity, the PTEN G129R mutation detected in RMS should have an oncogenic effect. The allele frequency of the PTEN A120P mutation was 0.84, and in accordance with this finding, the SNP array analysis disclosed uniparental disomy involving the PTEN locus by which the mutated allele was duplicated. Thus, the A120P substitution is likely to be an oncogenic mutation rather than a non-functional SNP. Although somatic mutations in GAB1 and ROBO1 have been reported in several cancers, the role of these genes in the RMS pathogenesis is unknown22,23,24.

Probably, the most significant finding in the current study would be the identification of the novel methylation clusters, which tightly correlated with genetic abnormalities, histological subtypes and clinical behaviours, underscoring the importance of integrated molecular analyses. Importantly, this finding revealed an otherwise unrecognizable subset of ERMS that showed a poor prognosis (E2 cluster) for which intensification or novel therapeutic approaches need to be considered. We also found an extremely high frequency of epigenetic silencing of PTEN in ERMS. PTEN is one of the most frequently mutated tumour suppressors in human cancers and is also essential for embryonic development25. PTEN modulates G1 cell cycle progression by negatively regulating the FGFR4/PI3K/AKT axis. Thus, the finding that PTEN methylation/mutation is highly specific to and frequent in the E1/E2 tumours indicates that PTEN may serve as a diagnostic marker to identify those patients for which inhibition of the FGFR4/PI3K/AKT axis could have a key therapeutic role. Finally, the biological/genetic basis for these distinct methylation clusters, nevertheless, is currently unknown and it should be addressed in future studies. Since our single cohort in the current study is very limited, to provide an adequate assessment of molecular subgroups, more large number of independent cohorts should be evaluated.

Methods

Samples

This study cohort comprised 66 tumours from 60 cases with RMS (22 ARMS, 35 ERMS, one mixed type, one RMS, not otherwise specified, and one unknown histology. Matched normal specimens (mononuclear cells from peripheral blood or bone marrow at diagnosis or in remission) were available in 16 cases, which were subjected to whole-exome sequencing. In three ARMS cases, samples from both primary and recurrent or metastatic tumours were available, which were analysed by whole-exome sequencing. Detailed information on subjects and samples is provided in Supplementary Data 1 and 3. To generate sufficient DNA templates of tumour and germline DNA in a subset of cases in which enough samples were not available, whole-genome amplification was performed using the REPLI-g kit (Qiagen). The amplified DNAs were used in part for targeted deep sequencing to validate individual candidate mutations detected in whole-exome sequencing; to analyse all coding sequences of possible candidate genes in the validation cohort. Written informed consent for research use was obtained from patients’ parents, and this study was approved by the Human Genome, Gene Analysis Research Ethics Committee of the University of Tokyo.

Whole-exome sequencing

In 19 samples from 16 cases, whole-exome capture libraries were constructed from tumour and matched normal DNA using Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon 50 Mb, V4 or V5 (Agilent Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Enriched exome libraries were sequenced with the Hiseq 2,000 platform (Illumina). For identifying candidates for somatic mutations from exome-sequencing data, the EBcall (Empirical Bayesian mutation calling)26 algorism was used. This algorism discriminates somatic mutations from sequencing errors based on an empirical Bayesian method using sequencing data of multiple non-paired germline samples.

RNA sequencing

In eight tumour samples from our RMS which high-quality RNA (that is, RNA integrity number >6.0) was available, RNA sequencing was performed using Hiseq 2,000. RNA sequencing libraries were prepared using the Truseq RNA Sample Preparation kit (Illumina). Candidates of fusion transcripts were identified using Genomon-fusion. All candidates of gene fusion, which represented more than two paired-reads were subjected to confirm by RT–PCR-based Sanger sequencing. The primer sets used for RT–PCR analysis were listed in Supplementary Data 7.

Validation of putative somatic variants

To validate putative genomic variants detected in whole-exome sequencing, targeted deep sequencing was performed27. Regions encompassing possible variations were amplified with NotI-tagged primers. Pooled PCR amplicons were digested with NotI, followed by ligation with T4 DNA ligase. Ligated PCR amplicons were sonicated into fragments of an average size of 200 bp using a Covaris sonicator. After being enriched and multiplexed, the prepared libraries were subjected to deep sequencing using Illumina Hiseq 2,000 or Miseq with a 100-bp or 150-bp pair-end reads option. Both tumour and germline DNA were examined to confirm somatic variations. Selective variants of which PCR primers could be constructed by Primer 328,29 were subjected to deep sequencing for validation. The validated mutations are listed in Supplementary Data 2.

Evaluation of mutation candidates

For 14 candidate genes, including recurrent mutated genes in exome sequencing (TP53, BCOR, ARID1A, GAB1, ROBO1, PTEN and KRAS), and the associated genes (FGFR4, PIK3CA, HRAS, NRAS, PTPN11, NF1 and FBXW7), PCR-based deep sequencing of the candidate genes was performed in 66 samples using Hiseq 2000 or Miseq (Illumina). NotI-tagged primers (Supplementary Data 17) were used to generate each PCR amplicon. Selected exons were sequenced for FGFR4, PIK3CA and PTPN11. Sample preparation, data processing and variant detection were performed as described above in the methods section of Validation of putative somatic variants.

DNA methylation analysis

In 53 RMS samples from 50 cases, comprehensive DNA methylation analysis was performed with the Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip (Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Beta-values were converted to M-values30, then pcaMethods bioconductor R package was used to impute incomplete data. M-values were converted to beta-values again and imputed beta-values were used for further analyse. To determine the DNA methylation profiles, the following steps were adopted to select probes for unsupervised clustering analysis. We first removed probes that were designed for sequences on the X and Y chromosomes. Second, we selected probes with variance ranked in the top 1% of the remaining probes. We then performed unsupervised hierarchical clustering with 4,708 probes, identifying 4 distinct clusters. To detect methylation status compared with normal skeletal muscles, published data of the same 450 k platform was used31. Wilcoxon rank-sum test was performed to select differentially methylated probes. To detect differentially methylated genes for each sample, multiplicative decomposition model of gene methylation was adopted. Let xijk be the beta value at probe location j within 1,500 bps of the transcription start site of gene k for RMS sample i, cjk be the average beta value at the same location of the same gene for 48 normal skeletal muscle samples, n be the number of samples, g be the number of genes, and pk be the number of probes within 1,500 bps of transcription start site of gene k. For each gene k, we consider a following multiplicative model of the two-way table of gene methylation changes:

where eijk is an observation error, aik is the methylation pattern depending on sample i, and bjk is the methylation pattern depending on probe location j, respectively. The parameters aik, i=1,…,n and bjk, j=1,…,pk are estimated by Bayesian principal component analysis32. The signs of aik, i=1,…,n are chosen so that they are proportional to the average beta value of pk locations of gene k. The z-score to see if aik is significantly larger or smaller than those of the normal skeletal muscles is then calculated by:

where  and

and  are the average and s.d. of the sample-dependent methylation patterns for the normal skeletal muscles, respectively.

are the average and s.d. of the sample-dependent methylation patterns for the normal skeletal muscles, respectively.

For a given threshold T, we can declare the methylation status of gene k for sample i to be an aberration compared with that of normal skeletal muscles if |zik|>T. Here identifying aberrations can be thought of as a multiple-testing problem where we are testing the following hypothesis for each gene within each sample:

An estimator of the false discovery rate33 for threshold T can be calculated by

The threshold T is then chosen so that  .

.

Quantitative RT–PCR

Quantitative RT–PCR for PTEN was performed in 19 samples from which enough RNA was available. RNA (200 ng) extracted from the fresh-frozen tumours were subjected to reverse transcription using the SuperScript VILO MasterMix (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative mRNA expression levels were measured using the QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR kit (Qiagen, Tokyo, Japan) with an iCycler iQ real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). The optional thermal-cycling condition was as follows: 40 cycles of a two-step PCR (95 °C for 15 s, 58 °C for 60 s) after the initial denaturation (95 °C for 10 min). For the purpose of normalization, relative expression levels were calculated by dividing the expression level of the respective gene by that of GAPDH34. Primers used for quantitative RT–PCR are listed in Supplementary Data 18.

Bisulfite conversion and bisulfite sequencing of PTEN

To confirm PTEN methylation, bisulfite sequencing using nested primers was performed. Genomic DNA (500 ng) was bisulfite-modified using the EpiTect Plus DNA Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Primer sequences for PCR amplicons are listed in Supplementary Data 18. Complete bisulfite modification was confirmed by bisulfite sequence analysis of the replicated normal DNA.

Bisulfite sequencing for validation of methylation array

To validate the result of DNA methylation array, targeted bisulfite deep sequencing was performed. Five samples among each cluster were randomly selected for validation. As positive controls, two samples of replicated normal DNA were also analysed by bisulfite sequencing. Genomic DNA (1,000 ng) was bisulfite modified using the EpiTect Plus DNA Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Among extracted 266 probes (E1/E2 versus A1/A2, E1 versus E2 and A1 versus A2), we selected probes to validate, which recurrently detected in three or more. Finally, 160 probes were subjected to target deep sequencing. Bisulfite PCR was performed in 22 samples (20 tumours and two controls) with NotI-tagged primes as described above. For data analysis, the same method of targeted deep sequencing was used, with modified mapping to bisulfite converted reference genome. Methylated cytosine was calculated as variant allele frequency. Validated probes were listed in Supplementary Data 19. The Spearman correlation coefficient was used to compare beta-values and methylated allele frequencies.

Pathway analysis

Ingenuity pathway analysis (http://www.ingenuity.com/) was performed for extracted genes listed in Supplementary Data 8–10.

SNP array analysis

DNA extracted from RMS samples was subjected to SNP array analysis using Affymetrix GeneChip 250K Nsp or CytoScan HD (Affymetrix) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Details regarding the use of these platforms are listed in Supplementary Data 1 and 3. CNAG/AsCNAR software was used for subsequent informatics analysis for SNP array data, which enables accurate detection of allelic status without paired normal DNA, even in the presence of up to 70–80% normal cell contamination35,36. Significant focal CN alterations were identified using GISTIC 2.037 for 250 k array data. The array data have been partially published in the previous our paper3.

Analyses of PAX gene fusions

The status of the PAX3/7–FOXO1 fusion gene was examined by RT–PCR followed by Sanger sequencing in 34 tumours for which RNA or cDNA was available. The primers and the PCR condition are listed in Supplementary Data 20.

Statistical analysis

Fisher’s exact test was used to evaluate the differences in chromosomal CN changes between ARMS and ERMS or the correlation between CN changes and prognosis in each subgroup. The numbers of mutations or CN changes were compared by t-test.

Additional information

Accession codes: Whole-exome sequence data and the methylation microarray data has been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive, hosted by the European Bioinformatics Institute, under the accession code EGAS00001000884. The SNP array data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE41263 and GSE63891.

How to cite this article: Seki, M. et al. Integrated genetic and epigenetic analysis defines novel molecular subgroups in rhabdomyosarcoma. Nat. Commun. 6:7557 doi: 10.1038/ncomms8557 (2015).

References

Ognjanovic, S., Linabery, A.M., Charbonneau, B. & Ross, J.a. Trends in childhood rhabdomyosarcoma incidence and survival in the United States, 1975-2005. Cancer 115, 4218–4226 (2009).

Malempati, S. & Hawkins, D.S. Rhabdomyosarcoma: review of the Children's Oncology Group (COG) Soft-Tissue Sarcoma Committee experience and rationale for current COG studies. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 59, 5–10 (2012).

Nishimura, R. et al. Characterization of genetic lesions in rhabdomyosarcoma using a high-density single nucleotide polymorphism array. Cancer Sci. 104, 856–864 (2013).

Liu, C. et al. Analysis of molecular cytogenetic alteration in rhabdomyosarcoma by array comparative genomic hybridization. PLoS ONE 9, e94924 (2014).

Breneman, J.C. et al. Prognostic factors and clinical outcomes in children and adolescents with metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma--a report from the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study IV. J. Clin. Oncol. 21, 78–84 (2003).

Chen, X. et al. Targeting oxidative stress in embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer cell 24, 710–724 (2013).

Shern, J.F. et al. Comprehensive genomic analysis of rhabdomyosarcoma reveals a landscape of alterations affecting a common genetic axis in fusion-positive and fusion-negative tumors. Cancer Discov. 4, 216–231 (2014).

Kohsaka, S. et al. A recurrent neomorphic mutation in MYOD1 defines a clinically aggressive subset of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma associated with PI3K-AKT pathway mutations. Nature Genet. 46, 595–600 (2014).

Bellacosa, A. Role of MED1 (MBD4) Gene in DNA repair and human cancer. J. Cell Physiol. 187, 137–144 (2001).

Alexandrov, L.B. et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 500, 415–421 (2013).

Vi, J.G.T. et al. Identification of FGFR4 -activating mutations in human rhabdomyosarcomas that promote metastasis in xenotransplanted models. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 3395–3407 (2009).

Samuels, Y. et al. High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science 304, 554 (2004).

Campbell, I.G. et al. Mutation of the PIK3CA gene in ovarian and breast cancer. Cancer Res. 64, 7678–7681 (2004).

Rosty, C. et al. PIK3CA activating mutation in colorectal carcinoma: associations with molecular features and survival. PLoS ONE 8, e65479 (2013).

Barr, F.G. et al. In vivo amplification of the PAX3-FKHR and PAX7-FKHR fusion genes in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Hum. Mol. Genet. 5, 15–21 (1996).

Weber-Hall, S. et al. Novel formation and amplification of the PAX7-FKHR fusion gene in a case of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 17, 7–13 (1996).

Laverriere, A. C. et al. GATA-4/5/6, a subfamily of three transcription factors transcribed in developing heart and gut. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 23177–23184 (1994).

Molkentin, J.D. The zinc finger-containing transcription factors GATA-4, -5, and -6. Ubiquitously expressed regulators of tissue-specific gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 38949–38952 (2000).

Mahoney, S.E., Yao, Z., Keyes, C.C., Tapscott, S.J. & Diede, S.J. Genome-wide DNA methylation studies suggest distinct DNA methylation patterns in pediatric embryonal and alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas. Epigenetics 7, 400–408 (2012).

Li, J. et al. PTEN, a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase gene mutated in human brain, breast, and prostate cancer. Science 275, 1943–1947 (1997).

Wang, S.I. et al. Somatic mutations of PTEN in glioblastoma multiforme. Cancer Res. 57, 4183–4186 (1997).

Sjöblom, T. et al. The consensus coding sequences of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science 314, 268–274 (2006).

Ortiz-Padilla, C. et al. Functional characterization of cancer-associated Gab1 mutations. Oncogene 32, 2696–2702 (2013).

Biankin, A.V. et al. Pancreatic cancer genomes reveal aberrations in axon guidance pathway genes. Nature 491, 399–405 (2012).

Yamada, K.M. & Araki, M. Tumor suppressor PTEN: modulator of cell signaling, growth, migration and apoptosis. J. Cell Sci. 114, 2375–2382 (2001).

Shiraishi, Y. et al. An empirical Bayesian framework for somatic mutation detection from cancer genome sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e89–e89 (2013).

Yoshida, K. et al. Frequent pathway mutations of splicing machinery in myelodysplasia. Nature 478, 64–69 (2011).

Untergasser, A. et al. Primer3--new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e115–e115 (2012).

Koressaar, T. & Remm, M. Enhancements and modifications of primer design program Primer3. Bioinformatics 23, 1289–1291 (2007).

Du, P. et al. Comparison of Beta-value and M-value methods for quantifying methylation levels by microarray analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 11, 587 (2010).

Zykovich, A. et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation changes with age in disease-free human skeletal muscle. Aging Cell 13, 360–366 (2014).

Oba, S. et al. A Bayesian missing value estimation method for gene expression profile data. Bioinformatics 19, 2088–2096 (2003).

Klipper-Aurbach, Y. et al. Mathematical formulae for the prediction of the residual beta cell function during the first two years of disease in children and adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Med. Hypotheses 45, 486–490 (1995).

Takita, J. et al. Aberrations of NEGR1 on 1p31 and MYEOV on 11q13 in neuroblastoma. Cancer Sci. 102, 1645–1650 (2011).

Nannya, Y. et al. A robust algorithm for copy number detection using high-density oligonucleotide single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping arrays. Cancer Res. 65, 6071–6079 (2005).

Yamamoto, G. et al. Highly sensitive method for genomewide detection of allelic composition in nonpaired, primary tumor specimens by use of affymetrix single-nucleotide-polymorphism genotyping microarrays. Am. J.Hum. Genet. 81, 114–126 (2007).

Mermel, C.H. et al. GISTIC2.0 facilitates sensitive and confident localization of the targets of focal somatic copy-number alteration in human cancers. Genome Biol. 12, R41–R41 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Ms Matsumura, Ms. Hoshino, Ms Yin, Ms Saito, Ms Mori and Ms Ogino for their excellent technical assistance. We also wish to express our appreciation to Dr M-J. Park, Gunma Children’s Medical Hospital and Dr Y. Arakawa, Saitama Children’s Medical Hospital, for collecting samples. This work was supported by KAKENHI (25253095 and 26293242) of Japan Society of Promotion of Science; Research on Measures for Intractable Diseases, Health, and Labor Sciences Research Grants, Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare; by Research on Health Sciences focusing on Drug Innovation; by the Japan Health Sciences Foundation; by Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology, Japan Science and Technology Agency; and by The Project for Development of Innovative Research on Cancer Therapeutics (P-DIRECT) (886695).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S., R.N., N.H. and K.Y. performed DNA sequencing. Y.Shiraishi, T.S., K.C., H.T., Y.Shiozawa, Y.O. and S.M. performed bioinformatics analyses of the sequencing data. R.N., Y.Sato and M.K. performed SNP array analysis. M.S., T.S., G.N. and H.A. performed methylation analysis. M.K., H.H., Y.T., H.O., M.M., R.S., T.T., K.Koh, R.H., K.Kato, Y.N., M.A. and Y.H. provided specimens and were also involved in planning the project. M.S., K.Y., K.M., S.O. and J.T. generated figures, tables and supplementary information. M.S., S.O. and J.T. wrote the manuscript and A.O., T.I., Y.H., S.O. and J.T. edited the main text and figures. S.O. and J.T. led the entire project. All authors participated in the discussion and interpretation of data and results.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Figures

Supplementary Figures 1-10 (PDF 2378 kb)

Supplementary Data 1

Patient characteristics of RMS cases analyzed by next generation sequencing. (XLSX 57 kb)

Supplementary Data 2

List of detected mutations by whole exome sequencing. (XLSX 77 kb)

Supplementary Data 3

Patient characteristics of validation cohort. (XLSX 73 kb)

Supplementary Data 4

List of detected mutations by targeted deep sequencing. (XLSX 58 kb)

Supplementary Data 5

Significant gain regions detected by GISTIC analysis. (XLSX 73 kb)

Supplementary Data 6

Significant loss regions detected by GISTIC analysis. (XLSX 57 kb)

Supplementary Data 7

Validated fusion transcripts detected in RNA sequencing. (XLSX 74 kb)

Supplementary Data 8

Differentially methylated probes between cluster E1/E2 and A1/A2. (XLSX 50 kb)

Supplementary Data 9

Differentially methylated probes between cluster E1 and E2. (XLSX 47 kb)

Supplementary Data 10

Differentially methylated probes between cluster A1 and A2. (XLSX 33 kb)

Supplementary Data 11

Pathway analysis for gene list of E1/E2 vs. A1/A2. (XLSX 19 kb)

Supplementary Data 12

Functions annotation analysis for gene list of E1/E2 vs. A1/A2. (XLSX 37 kb)

Supplementary Data 13

Pathway analysis for gene list of E1 vs. E2. (XLSX 18 kb)

Supplementary Data 14

Functions annotation analysis for gene list of E1 vs. E2. (XLSX 34 kb)

Supplementary Data 15

Pathway analysis for gene list of A1 vs. A2. (XLSX 19 kb)

Supplementary Data 16

Functions annotation analysis for gene list of A1 vs. A2. (XLSX 35 kb)

Supplementary Data 17

Primer sets for targeted deep sequencing. (XLSX 21 kb)

Supplementary Data 18

Primer sets for nested PCR of bisulfite sequencing and RT-PCR in PTEN. (XLSX 9 kb)

Supplementary Data 19

Selected probes for validation of methylation array and primer sequences for bisulfite targeted deep sequencing. (XLSX 19 kb)

Supplementary Data 20

Primer sequences for RT-PCR. (XLSX 8 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Seki, M., Nishimura, R., Yoshida, K. et al. Integrated genetic and epigenetic analysis defines novel molecular subgroups in rhabdomyosarcoma. Nat Commun 6, 7557 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8557

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8557