Abstract

Behçet’s disease is a rare and poorly understood vasculitis affecting blood vessels of all types and sizes. Uveitis and oral and genital ulcers represent the typical clinical triad. Populations along the ancient trading route connecting the Mediterranean basin with the Middle and Far East are most affected. Up to a quarter of the cases has a pediatric onset, typically around puberty. The aim of the treatment is early intervention to control inflammation, with symptom relief and prevention of relapses, damage, and complications. The heterogeneous clinical presentation often requires a multidisciplinary and tailored approach. Ocular, neurological, gastrointestinal, and vascular involvement is associated with a worse prognosis and needs more aggressive treatments. In young patients with expected prolonged disease, treatment should also focus on preventive measures and lifestyle advice. In recent years, the pharmacological armamentarium has grown progressively, although only a limited number of drugs are currently authorized for pediatric use. Most evidence for these drugs still derives from adult studies and experience; these are prescribed as off-label medications and are only available as adult formulations. Corticosteroids frequently represent the mainstay for the management of the initial acute phases, but their potential serious adverse effects limit their use to short periods. Different conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs have long been used. Many other biologic drugs targeting different cytokines such as interleukin-1, interleukin-6, and interleukin-17 and treatments with small molecules including the phosphodiesterase 4 and Janus kinase inhibitors are emerging as novel promising therapeutic agents. In recent years, a growing interest has developed around anti-tumor necrosis factor agents that have often proven to be effective in severe cases, especially in those with a gastrointestinal and ocular involvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

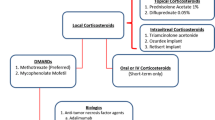

In the treatment of pediatric Behçet’s disease, topical medications are the first-line approach for mucocutaneous involvement. |

In the presence of unresponsive manifestations and severe and systemic disease, immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive therapies should be considered. |

Alongside the conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, a growing number of new biologics and targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs are more widely available. |

Tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors, alone or in combination with conventional treatment, are often remarkably effective for the treatment of different severe Behçet’s disease manifestations. |

1 Introduction

Behçet’s disease (BD) is a chronic systemic inflammatory disorder classically characterized by recurrent aphthous stomatitis, genital ulcers, and uveitis [1]. Nevertheless, this is a multi-system vasculitis able to involve blood vessels of all types and sizes, and any tissue or organ can be affected [2]. Worldwide frequency varies by geographical area, with the highest along the ‘Silk Route’ from the East of Asia to the Middle East including the countries around the Mediterranean basin. The countries most affected are Turkey (20–600 patients per 100,000 population), Iran (16.7–68/100,000), Israel (15.2–120/100,000), Iraq, and Southern Italy; while it is extremely rare in Western-North Europe (0.1/100,000 in Sweden), USA (0.33–5.2/100,000), and Africa [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Limited data are available relating to the epidemiology in the pediatric age group [11].

The pathogenesis of BD is still poorly characterized. A strong genetic component and different environmental factors seem to lead to an unbalanced immune response [12]. HLA-B51 is known to be the strongest genetic risk factor, correlating with a higher prevalence of genital ulcers and ocular and skin manifestations, but with a lower gastrointestinal (GI) involvement [13, 14]. A recent study in the pediatric population found an overexpression of Th17 lymphocytes linked to a functional inability of regulatory T cells to counterbalance the Th17 response during flares [15]. This finding is also supported by genome-wide association studies that have identified a link with a variant located in close proximity to the gene encoding the interleukin (IL)-23 receptor, a major inducer of Th17 differentiation [16, 17].

Among environmental factors, infections and microbiota play a crucial role [18, 19]. Behçet’s disease onset is usually between the second and fourth decade of life. In the Middle East, male individuals are more frequently affected and have a higher risk of developing a severe form of the disease [20].

According to a recent study from the autoinflammatory disease Alliance International registry, it appears that up to 26% of all patients with BD have onset of the disease from childhood, with a mean age that significantly varies between different studies from 4 to 15 years (10.92 ± 4.34, [2, 21, 22]. In pediatric-onset disease, with symptoms that gradually appear over time, the clinical picture is often incomplete with a risk of diagnostic delay [2, 21]. Manifestations may vary over time, on the basis of sex, age, and geographic area [23].

Recent evidence suggested that BD should be considered a syndrome with several phenotypes rather than a single disease [24,25,26,27,28]. Different clusters with different pathogeneses have been identified [26, 28, 29]. Ocular and intestinal involvements represent two different phenotypes that rarely overlap [28, 29].

The Pediatric BD Study Group observed a prevalent skin involvement in non-European children and musculoskeletal, GI, and neurologic manifestations mostly expressed in those from European countries [30]. The purpose of this review is to provide an overview of pediatric BD and to analyze treatment options in relation to different clinical spectrums.

2 Clinical Presentation

2.1 Mucocutaneous Involvement

Mucocutaneous lesions represent the most common presenting sign both in adults and children [21, 31]. Painful, isolated, or multiple oral aphthae can involve the tongue, lips, oral mucosa, gingiva, and occasionally palate. Rarely, oral ulcers may develop on the tonsils and oropharyngeal mucosa. Lesions are round with an erythematous border, they are usually smaller than 10 mm, but larger lesions (1–3 cm) may also occur. Ulcers usually heal in 3–10 weeks without scarring [32].

Painful genital ulcers usually occur in adolescent girls and these are characterized by a clear demarcation, considerable depth, and pain [32]. Genital ulcers are localized on the scrotum in boys and in the vulva and vagina in girls. They could heal with scarring, although less frequently than in adults [32, 33].

Severe skin lesions affect more than 90% of children. Pseudofolliculitis and erythema nodosum-like lesions are the most common manifestations, followed by folliculitis, pseudofollicolitis, papulopustular lesions, vesicles, palpable purpura, and pyoderma gangrenosum-like lesions [33, 34].

The pathergy test, a hyper-reactive reaction characterized by erythematous papules or pustules around the injection site 24–48 h after an intradermal puncture, although not pathognomonic, is a helpful sign for diagnosis [11]. This characteristic feature is more frequently observed in patients along the ancient Silk Road [31].

2.2 Ocular Involvement

Eye involvement is a frequent and potentially severe finding in pediatric BD, being described in 14–70% of children [32, 35]. In a cohort of 110 patients from 16 Italian tertiary centers, ocular disease was the second most common feature after oral ulcers [34]. It usually occurs 2–3 years after the disease onset, but in 10–20% of patients it is the presenting manifestation [36]. Eye disease is almost two-fold more frequent in male individuals [37]. Ocular symptoms include vision disturbances, photophobia, ocular redness, and eye pain [38].

In BD, the posterior segment is characteristically affected, while isolated anterior uveitis is uncommon and usually progresses rapidly to panuveitis [21, 39, 40]. Other findings include retinal vasculitis, keratitis, episcleritis, vitreitis, and optic neuritis. Cataract, glaucoma, maculopathy, retinal detachment, and posterior synechiae represent potential complications [41].

2.3 Vascular Involvement

Vascular damage occurs in 1.8–32.1% of pediatric patients, with a male predominance [42]. Both veins and arteries of every size may be affected, with the venous system more frequently affected [41]. Venous involvement is characterized by occlusion; lower extremity deep venous thrombosis and cerebral sinus thrombosis are among the major vascular events observed [34, 43, 44], while hepatic veins (Budd–Chiari syndrome) and inferior vena cava thrombosis are rarely described [45].

Aneurysm, pseudoaneurysm, stenosis, and thrombosis characterize arterial involvement. Pulmonary artery involvement and Budd–Chiari syndromes are associated with high morbidity and mortality. Male sex, young age, and the association with pro-thrombotic factors increase the risk of vascular complications [46]. Relapses are unusual compared with adult cases, which range from 0 to 21% of cases [42].

2.4 Neurological Involvement

Neurological involvement, neuro-BD (NBD), affects 3.6–59.6% of children [22, 32]. Mean age at neurological disease onset is 11.8 years, with a male predominance [47]. Neuro-BD encompasses two different types of manifestations: “non-parenchymal” (or vascular) and “parenchymal” (with acute and chronic progressive patterns). Pediatric patients usually present with the “non-parenchymal” disease, with cerebral venous thrombosis as the most frequent feature followed by pseudotumor cerebri [47, 48]. Parenchymal disease is mainly expressed with encephalomyelitis, aseptic meningitis, cranial nerve palsy, and neuropathy. Parenchymal lesions also affect the brainstem, basal ganglia, and spinal cord [49].

2.5 GI Involvement

Unspecific GI symptoms are often reported by children affected by BD, but a clear organic involvement is less commonly documented. Gastrointestinal manifestations occur in a percentage of pediatric patients with BD between 4.8 and 56.5%, and it is more common in East Asian populations [22, 33, 34, 43]. Symptoms vary from abdominal pain, dyspepsia, diarrhea, and nausea to GI bleeding and weight loss [50].

Terminal ileum and ileocecal regions are typically affected by lesions that have the aspect of aphtae or deeper volcano-shaped ulcers with deep and defined margins and a focal distribution. The terminal ileum and ileocecal regions are typically affected by lesions that have the aspect of aphthae or round/oval-shaped ulcers with deep and defined margins and a focal distribution [51,52,53,54]. Arterial involvement may result in intestinal ischemia. Gastrointestinal complications encompass abscesses and perforation.

The diagnosis can be difficult when GI involvement is the presenting manifestation in the absence of other signs, or when symptoms are still mild and intermittent. Because of the lack of diagnostic biomarkers, the combination of different data such as clinical and radiological features and macro and microscopic appearances of mucosa are required for confirmation.

2.6 Articular Involvement

Musculoskeletal manifestations are reported in 20–50% of pediatric patients [21]. Arthralgia and oligoarthritis of large joints such as the ankles and knees, but also the elbows and wrists are the most common manifestations [30, 32, 34]. Sacroiliitis and enthesopathy may also be observed [55].

Arthritis is usually not erosive and often shows a self-limited or recurrent course [55].

3 Differential Diagnosis

The clinical heterogeneity of BD and the lack of pathognomonic features or tests require the exclusion of alternative conditions before confirming the diagnosis. The list of possible differential diagnoses is broad including infections, malignancies, and other autoimmune and rheumatological diseases such as HLA-B27-associated syndromes, reactive arthritis, or antiphospholipid syndrome, and conditions characterized by mucosal ulcers such as periodic fever, aphthous-stomatitis, pharyngitis, adenitis syndrome, or mouth and genital ulcers with inflamed cartilage syndrome [56, 57].

Viral, fungal, and bacterial infections, including tuberculosis, may mimic BD and should be taken into account, mostly in the presence of mucocutaneous, GI, and ocular involvement. Gastrointestinal BD significantly overlaps with inflammatory bowel disease, especially Crohn’s disease as both conditions present with GI symptoms, oro-mucosal ulcerations, skin features, uveitis, and musculoskeletal manifestations. Behçet’s disease preferentially affects the terminal ileum and the ileocecal region with a limited number of round ulcers without non-caseating granuloma [58]. Perianal lesions are only seldom observed in patients with BD and should alert to Crohn’s disease. According to the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendation, inflammatory bowel disease has to be excluded through a mucosal biopsy before attributing symptoms to BD [59].

An increasing number of new monogenic autoinflammatory disorders, with a very early onset and features resembling BD, have recently been reported. Papadopoulou et al. described 11 children with a median age at the disease onset of 0.6 years, and a positive family history for BD in more than half of the cases. Although initially suspected with BD, they were ultimately diagnosed with a monogenic disease related to mutations in TNFAIP3, WDR1, NCF1, AP1S3, LYN, MEFV and GLA, STAT1, or TNFRSF1A [60, 61].

Early presentation (< 5 years of age), a positive family history and/or incomplete or atypical clinical features (even in older patients) should be considered ‘red flags’ suggestive for monogenic autoinflammatory diseases or primary immunodeficiencies [62]. Many different diagnostic/classification criteria have been developed over time, and until a few years ago, the most used were the 1990 international diagnostic criteria for BD defined by the International Study Group [63].

In 2014, to increase the sensitivity over the International Study Group criteria, the International Team for the Revision of the International Criteria for BD proposed a scoring system based on new different weight criteria including vascular and neurologic manifestations [64]. In 2015, the Pediatric BD study established the classification criteria in the pediatric population on the basis of a large prospective international cohort [30]. At least three out of six equal-weight criteria were required to confirm the diagnosis with a sensitivity of 91.7% and a specificity of 42.9%. Table 1 shows the comparison between these criteria.

4 Prognosis

Currently, there are no disease activity measures validated for the pediatric population. Few studies have applied the existing adult disease activity index. Batu et al. described a positive correlation between the Physician Global Assessment with both Iranian BD Dynamic Activity Measure and BD Current Activity Form, suggesting the potential role of these measures for pediatric trials [65].

Behçet’s disease is characterized by a relapsing-remitting course [2, 66]. Because of conflicting study results, there is currently no strong evidence of a direct influence of age at onset on disease prognosis [2, 67,68,69,70,71].

The literature is currently lacking in long-term prospective studies evaluating the prognosis in pediatric BD. Ocular involvement represents the main cause of disability; vascular and neurological involvement and intestinal perforation have been associated with a higher morbidity and mortality rate [11].

In the general population, the overall mortality reaches 5% at 10 years. Male sex, arterial involvement, and a higher number of flares have shown an independent association with mortality [72]. Some authors reported less severity in juvenile disease. A retrospective analysis from three tertiary centers showed a lower rate of major organ involvement and a lower prevalence of HLA-B51, a genetic marker associated with a more severe course [68].

In a series of 65 children and adolescents, the mortality rate was 3% and was related to large-vessel involvement [73]. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment are decisive in determining the outcome.

5 Treatment

The increasing availability of new treatments has improved the management of BD (Table 2 summarizes ongoing and concluded clinical trials on pharmacological treatments for BD). Behçet’s disease is a multi-system disease, able to affect several organ systems, inducing different clinical manifestations, with different severity and prognoses. A personalized management tailored to the specific clinical features is more appropriate than a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach, and specialized multi-disciplinary care is often required. The treatment is focused on controlling inflammation and symptom relief with the prevention of relapses, damage, and complications. Ocular, neurological, GI, and vascular manifestations are associated with a worse prognosis and require a more aggressive approach. The pharmacological armamentarium includes only a limited number of authorized drugs. This is true even more so in the pediatric population, where treatments mainly derive from adult studies and experience, and the management generally follows the recommendations released for adults. Among clinical practice guidelines, the 2018 EULAR recommendations, the 2020 Japanese guidelines, and the 2021 French recommendations represent the most used tools in aiding healthcare decision making [59, 74, 75]. French recommendations also offer a clinical and therapeutic overview on the pediatric population.

5.1 General Measures

General preventive measures and lifestyle advice such as the promotion of a balanced diet, physical activity, and immunization are part of the initial care of young patients with BD. Pre-adolescents and adolescents need to be educated about safe and effective contraception and drug abuse risks.

As in children with autoimmune diseases who may require an immunosuppressive treatment, vaccination status also needs to be investigated in pediatric patients with BD, and age-appropriate vaccines should ideally be administered before starting immunosuppressive treatments, particularly for live-attenuated vaccines [76, 77]. Seasonal influenza vaccines and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines are also recommended.

The EULAR viewpoint supports severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 vaccination in patients with rheumatic diseases [78]. However, some case reports described new-onset BD symptoms after vaccination. Some studies on vaccinated patients with BD highlighted an increased frequency of disease flare-up compared with patients affected by classical forms of rheumatic diseases [79, 80]. The authors supposed that this may be related to the involvement of innate immunity in BD and recommended close monitoring of patients after vaccination [81].

Glucocorticoids are frequently used in the management of BD. Their potential side effects need to be detected early, ideally prevented by educating patients and their families about the risk of potential behavioral and cognitive changes, and the symptoms of adrenal insufficiency [82]. Patients also need to be educated about the benefits of regular physical exercise, a low-sodium, low-fat, and low-sugar diet, and of calcium and vitamin D supplementation.

Adolescents should receive contraceptive advice and counseling and need to have access to reproductive health services [83]. Because of the risk of thrombosis, female traditional risk factors need to be assessed, the best contraceptive methods discussed and, in patients taking multiple medications, potential interactions should be checked.

Data on the transition to vasculitis in adolescents are limited [84]. Emotional lability and a fragile sense of self are part of adolescence. A chronic disease such as BD may represent a further psychosocial stress that can complicate relationships with peers and the development of a positive body image, and negatively influence adherence to treatments. Although experience of other rheumatological conditions can provide transition models for BD, randomized controlled trials focused on identifying the best transition practices, guidelines, and recommendations are still an unmet need in this condition.

5.2 Mucocutaneous Involvement

5.2.1 Topical Measures

Topical measures, often available without a prescription, represent the first-line approach for mucocutaneous lesions. Some controlled studies have been conducted on topical drugs in BD; however, no standard treatment has yet been defined. A larger number of studies have been published on treatments for recurrent aphthous stomatitis, an even more frequent condition, and then adapted in BD clinical practice [85]. Ulcers, despite being self-limiting and non-life-threatening manifestations, may deeply affect the quality of life [86]. Topical interventions range from oral health promotion to inert barriers to active treatments such as sprays, mouth rinses, locally dissolving tablets, pastes, or gels. Discomfort and pain linked to mucosal lesions may contribute to a poor oral hygiene practice, which in turn induces infective foci, worsening of local inflammation, and dysbiosis, and may contribute to increase systemic disease activity [87]. Dental plaque accumulation is associated with a more severe disease course [88].

Difficulties in eating and drinking may lead to an inadequate nutrient intake, causing deficiencies in vitamins and iron that may contribute to increase mucous membrane fragility [89]. Oral hygiene education and a regular dental check-up should be considered a part of the general preventive measures, even more so in immunosuppressed patients. Topical antiseptics such as chlorhexidine oral rinses or chlorhexidine-based gel applications play a role in plaque control by reducing ulcer severity and pain [90]. When an infectious triggering factor is suspected, antibiotics may be useful as observed for minocycline and azithromycin [91]. Topical analgesic and anesthetic agents such as 2% lidocaine (spray or gel) help with pain relief [92]. A support in barrier forming and ulcer healing can be offered by the application of 0.2% hyaluronic acid gel or by hyaluronic acid mouthwashes [93].

Sucralfate, an aluminum salt of sucrose sulfate, usually prescribed as a peptic ulcer treatment, was ineffective in the prevention of BD oral ulcers [94], while in a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study, Alpsoy et al. observed sucralfate to be effective with pain control, and shortened the healing time for both oral and genital ulcers [95].

A non-steroidal anti-inflammatory mouthwash or spray two to four times a day can also be applied, such as diclofenac 3%, amlexanox oral paste 5%, enzydamine hydrochloride 1.5 mg/mL (0.15%), and choline salicylate 8.7% [96, 97]. Triamcinolone acetonide, dexamethasone, or hydrocortisone are among the most frequently used corticosteroids in these patients [98, 99]. Triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% appeared to be superior to phenytoin syrup for the treatment of aphthous ulcers [99].

Preparations with high-potency corticosteroids such as betamethasone or clobetasol can be considered in the presence of severe lesions [75]. In two placebo‐controlled trials, topical interferon-α was ineffective for the treatment of BD oral ulcers [100, 101]. Pentoxifylline gel may shorten the healing period and reduce the pain of oral ulcers in patients with BD [102].

5.2.2 Systemic Treatments

In the presence of severe oral lesions, unresponsive to topical treatments, in the presence of genital ulcers or erythema nodosum and in order to prevent their recurrence, systemic drugs should be taken into account. In these cases, colchicine represents an effective first-line treatment.

Colchicine primarily acts by inhibiting microtubule polymerization, downregulating many inflammatory pathways such as cell migration, division, polarization, intracellular vesicle motility, and secretion [103]. Colchicine has a narrow therapeutic window, thus dosage and concomitant renal or hepatic impairment should be carefully evaluated [104]. Gastrointestinal side effects may be expected, and they can be managed by dividing the daily dose into two administrations. Colchicine is metabolized by cytochrome P450 3A4 in the liver with a prevalent hepatobiliary excretion. Colchicine is a substrate for the P-glycoprotein 1 reflux transporter [103, 105]. Concomitant use of molecules interferes with these two complexes such as cyclosporine, clarithromycin, ketoconazole, calcium channel blockers, and clarithromycin, but also natural grapefruit juice increases the risk of toxicity [106]. Colchicine has US Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of familial Mediterranean fever in patients from 4 years of age. The efficacy of colchicine for the treatment of oral lesions in BD shows some controversies, while it seems to be satisfactory for genital ulcers and other skin lesions, as underlined in the 2018 EULAR recommendations [59].

Cabras et al., in a systematic review focused on the efficacy of colchicine in the treatment of oral ulcerations, identified four randomized controlled trials in adult patients with BD [107]. Two double-blind placebo-controlled trials, one by Aktulga et al., the other by Yurdakul et al, in 2001, did not find differences between the two groups, while Davatchi et al. in a randomized, double-blind, controlled crossover trial published in 2009 documented colchicine to be significantly more effective than placebo in reducing the mean disease activity index of oral aphthosis measured with the Iranian BD Dynamic Activity Measure score [108,109,110].

Masuda et al. published a double-blind trial where ciclosporin tested against colchicine was superior in oral aphthous ulcer treatment [111]. Colchicine significantly reduces the occurrence and number of genital ulcers and erythema nodosum lesions and it is effective in pseudofolliculitis treatment [109, 110]. French recommendations for the management of pediatric and adult BD suggest a single daily dose regimen of 1–2 mg/day for a minimum of 3–6 months before declaring its ineffectiveness [75].

The EULAR recommendations for familial Mediterranean fever indicate a starting dose of ≤0.5 mg/day in children <5 years of age, 0.5–1.0 mg/day in those 5–10 years of age, and 1.0–1.5 mg/day in patients older than 10 years of age [112]. Patients with mucocutaneous flares can benefit from the association of topical corticosteroids and, in selected cases, from short-term oral corticosteroid cycles. In refractory mucocutaneous lesions, alternative treatments may range from thalidomide to apremilast, pentoxyphylline, dapsone, azathioprine, interferon (IFN)-α, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibitors.

Azathioprine is an immunosuppressive agent widely used in clinical practice. It is converted into 6-thioguanin and is incorporated into DNA blocking the de novo pathway of purine synthesis. This drug has a beneficial effect on oral and genital ulcerations and arthritis [113].

Thalidomide promotes the degradation of TNFα messenger RNA, exerting an immunomodulatory, and anti-inflammatory function and an antiangiogenic activity [114]. Its use in pediatric BD and BD aphthosis is supported by limited though encouraging data, mostly based on clinical cases and a case where it has been used with a variable dosage from 1 mg/kg/week up to 20 mg/kg/day, usually 1–3 mg/kg/day [115,116,117]. One trial compared two different thalidomide dosages (300 mg daily and 100 mg daily) with placebo for the treatment of mucocutaneous lesions in adult BD, final results are difficult to clearly evaluate because of bias and some inaccuracies in the study profile; significant adverse events have been registered [118]. In a study on 21 cases of severe recurrent aphthous stomatitis, the efficacy of thalidomide, dapsone, colchicine, and pentoxifylline was analyzed; all these drugs had some benefits, but thalidomide was the most efficient and well tolerated, while dapsone was associated with the highest number of side effects [119]. The major, usually dose-limiting, side effects of thalidomide are fatigue, peripheral neuropathy, and constipation; taking the drug at bedtime and some diet and lifestyle indications may be helpful for patients.

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study, dapsone at a dosage of 100 mg/day was effective in reducing the number, duration, and frequency of oral ulcers and the number of genital ulcers in 20 adult patients with BD [120]. This drug exerts an anti-inflammatory action inhibiting neutrophil chemotaxis and interfering with the release of leukotrienes and prostaglandins [121].

Apremilast is an orally administered, small-molecule phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor able to interfere with several inflammatory pathways; it has recently been authorized for oral ulcers in adult patients with BD in the USA, Japan, and the European Union. Both EULAR and Japanese recommendations mention apremilast for the treatment of oral ulcers associated with BD [59].

A phase II, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial conducted in adult patients with BD with active oral ulcers showed this molecule to be effective in controlling the number of oral ulcers and related pain [122]. A phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled study confirmed the sustained beneficial effect over time, as well as its tolerability and safety profile in subjects with BD ≥18 years of age [123].

In a systematic literature review and meta-analysis, including real-world data, apremilast was shown to be effective also for genital ulcers, skin lesions, and arthritis and its use did not exclude concomitant classic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and/or biologic therapies [124]. Gastrointestinal symptoms are the most common side effects observed. A phase III, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04528082) is underway to analyze the efficacy and safety of apremilast in children (2–17 years of age) with active oral ulcers associated with BD, and the planned study completion date is 2028.

Anti-TNF-α agents allow a high rate of remission of oral and genital ulcers, erythema nodosum, and other skin manifestations, and are also useful in controlling articular inflammation [125]. In a 4-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, etanercept, a recombinant human TNF receptor Fc fusion protein, was effective at suppressing most of the mucocutaneous lesions [126]. Adalimumab emerged as a valid treatment for leg and recalcitrant genital ulcers also in patients in whom immunosuppressive therapy had failed [127, 128].

Still, limited studies are available on the potential role of IL-1 blockers in mucocutaneous manifestations. Anakinra, an IL-1 receptor antagonist administered subcutaneously, shows an acceptable safety and efficacy profile at a dosage of 200 mg/day in the treatment of resistant oral and genital ulcers as well as for musculoskeletal and intestinal manifestations; some reports also found canakinumab, a selective human monoclonal anti-IL-1β antibody administered subcutaneously monthly, to be a successful treatment for mucosal ulcers [129, 130].

Ustekinumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody directed against the p40 subunit of IL-12 and IL-23, was effective for the treatment of refractory oral lesions resistant to colchicine in two open-label prospective studies including 14 and 30 patients [131]. In a multicenter retrospective study involving 15 patients with oral and genital ulcers and articular symptoms who did not tolerate or were resistant to other treatments (colchicine, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, and at least one anti-TNFα agent), secukinumab appeared to be safe and effective in terms of control of mucosal and articular manifestations, especially in those patients treated with a dosage of 300 mg/month compared with those treated with 150 mg/month [132].

This drug is a fully human monoclonal antibody neutralizing IL-17A, administered as a subcutaneous injection every 4 weeks. It has recently received Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency approval for the treatment of pediatric patients with enthesitis-related arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and psoriasis. Some isolated reports, however, have highlighted de novo BD or BD exacerbation after starting secukinumab therapy [133, 134].

A mucocutaneous deterioration has been observed in patients with BD treated with tocilizumab, a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody anti-IL-6 receptor, when used for severe mouth and genital ulcers [135,136,137]. In another case successfully treated for neuro-BD, recurrence of oral ulcers has been observed [138].

A recent meta-analysis confirmed tocilizumab ineffective for mucocutaneous and articular manifestations with the possibility of a clinical exacerbation, while suitable for ocular, neurologic, and vascular involvement, as well as for secondary amyloidosis [139]. The divergent effect of tocilizumab on different BD expressions could be related to distinct underlying pathogenic mechanisms [135,136,137].

5.3 Ocular Involvement

No standardized protocols are available and, although treatment should be tailored to the clinical presentation, a prompt intervention should aim to rapidly resolve ocular inflammation, help to prevent new attacks, and contain potential complications.

5.3.1 Topical/Local Measures

In the presence of anterior segment inflammation, especially when uncomplicated, local corticosteroid eyedrops such as prednisolone acetate 1%, dexamethasone 0.1%, and prednisolone sodium phosphate 1% are the treatments of choice [140]. The frequency of administration should be gradually tapered after some weeks of application based on the degree of inflammation.

Difluprednate ophthalmic solution 0.05% has been found to be well tolerated and noninferior to prednisolone acetate 1% and with a less frequent dosing requirement (four times daily versus eight times daily) for the treatment of endogenous anterior uveitis, and it is also able to reach the posterior segments [141]. The association with topical cycloplegic/mydriatic agents such as cyclopentolate 1%, tropicamide 1%, and phenylephrine 2.5 and 10% is recommended to reduce pain through controlling ciliary muscle contraction, and breaking and/or preventing synechiae [142, 143].

In adults with severe, resistant, or recurrent anterior uveitis, periocular depot corticosteroid injections represent a helpful strategy especially in the presence of unilateral disease, avoiding systemic side effects; however, in the pediatric population, the experience is still limited [143, 144]. This therapeutic approach finds even more rationale in the management of posterior uveitis for which topical corticosteroids are ineffective, owing to their inability to penetrate the intermediate and posterior part of the eye [145].

Different injection sites can be used such as the subconjunctival or retrobulbar space and orbital floor transconjunctival approach, and various topical preparations are available such as dexamethasone triamcinolone or betamethasone that can be administered every 2–4 weeks for four to five times [146]. Although highly effective on local inflammation, periocular corticosteroid injections may induce an increase in intraocular pressure, cataracts, and local traumatic lesions.

In selected cases unresponsive to periocular injections or in those with vitreitis, intravitreal injections offer a valid alternative to release high drug concentrations into target tissues. A biodegradable capsule containing corticosteroids such as dexamethasone or fluocinolone acetonide can be intravitreally implanted with the advantage of a prolonged slow release ensuring drug delivery over a period of up to 6 months [147,148,149]. Although this system protects against the risk of corticosteroid systemic side effects, it predisposes to localized effects including cataracts and increased intraocular pressure.

In recent years, intravitreal drug delivery has progressively increased, also including other molecules. This strategy has been used to locally deliver inhibitors of the angiogenic mediator, vascular endothelial growth factor, which is upregulated in uveitis, mediating the pathogenesis of different complications such as retinal neovascularization, cystoid macular edema, and choroidal neovascularization. Data related to the intravitreal use of anti-vascular endothelial growth factors such as bevacizumab and ranibizumab seem to be encouraging, even if still limited [147, 150, 151]. On the contrary, in a prospective open-label pilot study, monthly intravitreal infliximab injections (1 mg/0.05 mL) in patients with BD with active posterior uveitis were ineffective and associated with a high complication rate [152].

5.3.2 Systemic Treatments

Posterior uveitis, panuveitis, and refractory and severe anterior uveitis require a systemic therapy. Young age, male sex, and early disease onset can be considered risk factors that should encourage consideration of systemic immunosuppressive treatment, also in those patients with an isolated eye involvement. Systemic corticosteroids represent a first-line therapy, acting as a bridging treatment for immunosuppressive agents providing strong and rapid anti-inflammatory actions.

Anterior uveitis can benefit from a short cycle of oral corticosteroids, usually prednisolone at a dosage of 0.5–1 mg/kg/day, to be slowly tapered once the inflammation is under control. Posterior uveitis and panuveitis attacks may require higher doses and a prolonged period of oral corticosteroids eventually preceded by intravenous methylprednisolone pulses (30 mg/kg/dose maximum 1 g/day for 1–3 consecutive days) to obtain a rapid anti-inflammatory effect [75]. Long-term treatments and high dosages should be avoided because of a broad array of serious adverse events and the inability to prevent ocular flares, and immunosuppressive corticosteroid-sparing agents started. On the base of 2018 EULAR recommendations, systemic immunosuppressive drugs include azathioprine, cyclosporine A, IFNα, or TNFα inhibitors [59].

In a randomized, placebo-controlled double-blind trial, azathioprine (2.5 mg/kg/day) was able to preserve visual acuity in patients with established eye disease, and prevent a new eye involvement in a small male BD Turkish cohort [113]. Azathioprine has long-term efficacy, is well tolerated, and is associated with a better outcome if started early [153, 154]. In more severe and resistant cases, azathioprine has been used in association with other drugs such as infliximab or cyclosporine, while the combination with IFNα is avoided because of the risk of myelosuppression [155,156,157].

Cyclosporine A, a selective calcineurin inhibitor, has been shown to be effective in preserving visual acuity and preventing ocular relapses at a dose of 3–5 mg/kg/day in two separated doses [111, 158, 159]. Because of an increased risk of neurologic and renal side effects, patients need to be selected on the basis of their BD spectrum and periodically followed up [160].

The pivotal role played by TNFα in the pathogenesis of this condition introduced TNF blockers into the therapeutic armamentarium. The rich literature produced on this topic is almost uniformly in agreement in supporting an overall beneficial effect of these drugs, especially infliximab and adalimumab, on different BD manifestations with a good safety profile [161]. Patients should be monitored for infections and, before treatment, tuberculosis and demyelinating disease need to be excluded [162]. In ocular involvement, infliximab and adalimumab can be used as first-line or second-line corticosteroid-sparing treatments [140]. The presence of retinal vasculitis may be associated with a worse response, suggesting an early initiation of these drugs in order to contain ocular inflammation and prevent retinal vasculitis [163].

Infliximab is an intravenously administered chimeric monoclonal antibody to TNFα, with a usual dose of 5 mg/kg (3–10 mg/kg) at weeks 0, 2, and 6 and then every 8 weeks. It is an effective option in recurrent and refractory anterior uveitis, posterior uveitis, and panuveitis [155, 164].

Infliximab can also play a beneficial effect on retinal vasculitis and macular thickness [165]. In panuveitis, a single infusion of infliximab has proven to be effective in significantly and rapidly decreasing cystoid macular edema [166]. This drug is Food and Drug Administration off-label used in BD and ocular diseases, while in 2007, it obtained approval in Japan for the treatment of refractory retinitis and uveitis [167].

Anti-drug antibodies, induced by the murine component of the drug, may predispose to side effects and a progressive loss of therapeutic effect [168]. Adalimumab, a fully recombinant human immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody administered subcutaneously at a dose of 40 mg/week (20 mg in patients <40 kg), is approved by the European Medicines Agency and the Food and Drug Administration authorized use in pediatric patients for noninfectious uveitis and it should be considered the first choice among anti-TNFα drugs. Adalimumab has been proven to control both anterior and posterior BD-related uveitis [169, 170].

Adalimumab and infliximab are both effective in BD ocular manifestations, and as corticosteroid-sparing drugs, with a similar relapse-free survival, although after 1 year of treatment adalimumab seems to have a better outcome in relation to visual acuity, anterior uveitis, and vitreitis [165, 171, 172]. On the basis of EULAR recommendations, switching is allowed when an adequate response is not obtained, while the association with other immunosuppressive drugs does not increase the result [59].

Golimumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody approved in pediatric patients for the treatment of polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, offers the advantage of a prolonged half-life with a monthly subcutaneous injection. It may represent a valid alternative in BD ocular involvement, as it was effective in the management of active retinal vasculitis and uveitis relapses in adults, although larger data on this drug are still lacking [171, 173, 174].

Methotrexate has been used for many years as a single drug or in combination and shown to be efficacious and able to ensure its therapeutic effect over time in noninfectious uveitis, especially in the absence of retinal vasculitis [175, 176]. In a longitudinal study on a large adult BD cohort, methotrexate (7.5–15 mg/week) improved the visual acuity in 46.5%, posterior uveitis in 75.4%, and retinal vasculitis in 53.7% of the eyes with an improvement in the total inflammatory activity index in 74% of patients [176].

In recent years, anti-IL-1 agents are emerging as new treatment strategies for BD, especially in the presence of ocular involvement. The most widely used IL1-1 blockers are anakinra, canakinumab, and gevokizumab, selective human monoclonal anti-IL-1β antibodies. The first encouraging results about the use of anakinra and canakinumab have been seen in case reports and small retrospective series, supporting their potential role as primary treatments for ocular BD [130, 177,178,179]. Both drugs have been found to have a good safety profile and provide a rapid and protracted response with a long-term drug survival [180]. Emmi et colleagues showed that reducing the infusion intervals could deal with an incomplete initial response to canakinumab, and a loss of response to anakinra can be overcome by a dose escalation or switching to canakinumab [181]. In two exploratory studies with a limited number of adult patients with BD, gevokizumab appeared to be safe and well tolerated, and to rapidly control ocular inflammation [182, 183]. In a subsequent prospective, randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled trial, gevokizumab failed to reduce the risk of ocular exacerbations, although it confirmed its good safety profile and effectiveness in preserving visual acuity, reducing the severity of uveitis, and limiting the risk of macular edema [184].

The beneficial effect of IFNα-2a in reducing the severity and the frequency of ocular BD attacks has been observed more than 20 years ago [185]. Interferonα-2a is usually injected subcutaneously three to seven times weekly, but there is still no consensus about the initial dose, which can range from 3 to 9 MIU[186]. Flu-like symptoms, local reactions, and alopecia are among the most common side effects associated with this treatment [186]. A satisfactory effect has been largely reported in BD uveitis, although with differently reported response rates, with a long-term remission achievement and a significant amelioration in visual outcomes [187,188,189,190]. With its prompt and long-term effect, IFN-α2 is indicated by 2018 EULAR recommendations for posterior initial uveitis and recurrent episodes of acute sight-threatening uveitis, representing a safe treatment alternative to conventional agents for refractory patients [59]. In a randomized, controlled, prospective clinical trial finalized to a head-to-head comparison between IFN-α and cyclosporine for the treatment of refractory BD uveitis, IFN-α obtained a higher rate of response, a greater improvement in visual acuity, and a more prolonged remission with an optimal tolerance rate [191]. Recent studies have reported similar efficacy and safety with infliximab and IFN-α2 in the treatment of refractory BD uveitis in adult patients [192, 193].

Although the Janus kinase (JAK)-STAT pathway seems to be implicated in the pathogenesis of BD, its role is still unclear and the use of JAK inhibitors in this condition is pioneering [194]. These small molecules offer the advantages of controlling multiple cytokine-dependent immune pathways and being orally available, which is usually more acceptable in young patients [195]. Janus kinase inhibitors seem to be a promising target for new therapeutic autoimmune uveitis strategies. In a mouse model of experimental autoimmune uveitis, tofacitinib that exerts a pan-JAK inhibition, significantly suppressed IFN-γ secretion and the development of uveitis, without influencing the adaptive IL-17 response [196]. The successful use of JAK inhibitors in the treatment of severe refractory non-infectious uveitis has been recently reported in some clinical cases [197,198,199,200]. A growing interest around JAK inhibitors is also expressed by the ongoing trials: two are phase II trials, one involving filgotinib (NCT03207815) and another involving tofacitinib (NCT03580343), and one is a phase III trial on pediatric patients affected by juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis (NCT04088409). Common side effects of JAK inhibitors are upper respiratory tract infections, GI symptoms, headache, or increased creatinine and cholesterol levels; major adverse events may include embolism and thrombosis, opportunistic infections, GI perforation events, and neoplasms [201].

Alkylating agents, owing to their low safety profile and their lack of efficacy from a systematic review from the Cochrane database, are not recommended for the treatment of BD ocular disease [202, 203]. In the SHEILD study, a randomized, placebo-controlled, multi-center phase III trial for BD uveitis, secuckinumab failed to reduce ocular exacerbations [204].

5.4 GI Involvement

The management of GI BD is tailored to the disease severity. Intestinal involvement may show a severe clinical course with complications such as perforation and massive bleeding requiring surgical intervention; in these cases, an aggressive approach including corticosteroids and/or immunomodulatory therapies is necessary.

Because of their potential side effects and an increased risk of GI bleeding, corticosteroids should be prescribed with a short-term low-dose program. Their use can be considered during the early phases of the induction, during the acute exacerbations, in the presence of moderate-to-severe activity, and in the presence of severe systemic manifestations. Prednisolone may be added with a starting dosage of 0.5–1.0 mg/kg/day, and only in selected cases, intravenous methylprednisolone boluses may precede the oral treatment in order to shorten the acute phase [205,206,207]. 5-Aminosalicylic acids, such as mesalamine, mesalazine, and sulfasalazine, are suitable in the induction and maintenance of remission in mild-to-moderate GI BD, in the absence of small bowel involvement [206, 208].

Anti-TNFα monoclonal antibodies, mostly infliximab and adalimumab, have gained a leading role in the treatment of GI BD. Infliximab was used for the first time in GI BD more than 20 years ago, since then, its use in this area has increasingly extended both for the treatment of moderate and severe forms, both for induction and maintenance, allowing corticosteroid sparing. The first encouraging data derived from isolated case reports, then larger retrospective and prospective studies confirmed the effectiveness and safety of this drug [209, 210].

In a prospective study involving 18 patients with BD of whom 11 had GI involvement unresponsive or intolerant to conventional therapy, infliximab induced a rapid and prolonged effect with a complete clinical response gradually increasing from 64% at week 30 to 80% at week 54, with a complete recovery of ulcerative lesions in more than 80% of the cases. Three out of 11 patients with intestinal BD needed a dose escalation from 5 to 10 mg/kg with a recovery of the therapeutic effect [211].

Results from an open-label single-arm multicenter study (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02505568) aimed at evaluating the efficacy and safety of infliximab in patients with moderate-to-severe refractory GI involvement are expected in the near future. In refractory cases, the combination with methotrexate induces a prompt and long-term response with an excellent tolerability [212].

A multicenter open-label uncontrolled study conducted in Japan evaluated the efficacy and safety of adalimumab in patients with refractory intestinal BD. The primary endpoint (values ≤1 for both the global GI symptom and endoscopic assessment scores at week 24) was obtained in 45% of the patients. Sixty-nine percent of the patients were able to taper or completely discontinue corticosteroids and an excellent response was documented for mucocutaneous manifestations [213].

In a Japanese phase III study on efficacy and long-term safety profiles, a significant improvement was observed in 60% of patients treated with adalimumab at week 52 and a complete remission in 20% of them, with a tolerable safety profile [214]. Real-world data confirmed these two anti-TNFα drugs to be effective in refractory GI BD and also suggested switching may be helpful in the case of failure of first-line anti-TNFα therapy [215].

Etanercept in a retrospective comparative study involving adult patients with BD obtained a higher remission rate of abdominal symptoms, and a higher healing rate of intestinal ulcers in respect to conventional (prednisone or methotrexate)-treated patients. A better recovery rate of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein and a better response in oral and genital ulcers with a reduced relapse rate were noted [126].

Azathioprine represents a choice in the treatment of moderate-to-severe intestinal BD. This drug offers a relatively good effect for the maintenance of remission in intestinal BD, although the relapse rate varies among different studies [216, 217].

Limited data support methotrexate as monotherapy for intestinal BD, while this drug is often used in association with anti-TNFα agents to reduce their immunogenicity [218, 219]. Georgiou et al. reported the successful use of subcutaneous human recombinant IFN-α-2a in 11 patients with refractory intestinal BD [220].

Some case series suggest thalidomide to be effective in the treatment of recurrent and perforating intestinal disease refractory to other treatments, with a better safety and efficacy profile also when compared with infliximab and adalimumab [116, 221, 222]. However, prospective trials are still lacking. In a pilot study on refractory BD, tofacitinib failed in GI control, although it was effective for vascular and articular manifestations and was well tolerated [223].

5.5 Neurological Involvement

Neuro-BD in the pediatric population is observed in around a quarter of the patients, representing a serious complication with potentially important consequences on morbidity and mortality. Neuro-BD in most of the cases is characterized by a parenchymal involvement that, on the basis of the clinical course, can be distinguished in an acute or chronic progressive type, and more infrequently by non-parenchymal or vascular disease. The acute parenchymal form usually shows a good response to corticosteroids and has a self-limiting course, while the progressive type has a chronic course requiring a prolonged immunosuppression [47].

The EULAR recommendations, which for the parenchymal involvement refer to the acute disease, have a level III of evidence and a strength of C [59]. Recommendations for the management of neuro-BD have also been released by the Japanese National Research Committee for Behçet’s Disease in 2020 including indications for both acute and chronic progressive parenchymal disease [224].

Acute parenchymal neuro-BD attacks need a prompt treatment with an intravenous bolus of methylprednisolone (30 mg/kg, to a maximum of 500–1000 mg/day, for 3–5 consecutive days), followed by oral prednisolone at 1 mg/kg/day for 3–4 weeks, then progressively tapered over 2–3 months. The management of corticosteroid withdrawal and the association with an immunosuppressive treatment are based and tailored on patient’s manifestations as no standardized schedules are available. The EULAR recommendations encourage the association of high-dose glucocorticoids (to slowly taper) with immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine for the treatment of acute attacks of parenchymal involvement, saving monoclonal anti-TNF antibodies for severe or refractory disease [59].

On the basis of French recommendations, the choice to introduce early an immunosuppressive agent can be eventually delayed in the case of the first episode of isolated meningitis responsive to corticosteroids [75], otherwise the association with an immunosuppressive drug should be taken into account while the patient is still receiving a high dose of corticosteroids. Azathioprine or methotrexate is indicated in moderate neuro-BD, and intravenous cyclophosphamide or infliximab in severe manifestations, as corticosteroids do not prevent the recurrence of attacks [225].

Azathioprine is initially administered with a low dosage of 1–2 mg/kg per day to test the tolerance and then gradually increased every 5–7 days up to 2–3 mg/kg per day [226]. In a small (n = 6) open trial, low doses of oral methotrexate (7.5–12.5 mg/week) have been reported to be beneficial for neuropsychiatric progressive manifestations during 12 months of administration with an exacerbation 6 months after its discontinuation [227].

In another study, a limited number of patients were treated for 4 years with small doses of methotrexate showing radiological and clinical substantial stability under treatment [228]. In a more recent retrospective study, patients treated with methotrexate have been studied for a prolonged period and a significant improvement in prognosis with a reduced mortality and deterioration rate was observed inducing authors to suggest a prompt initiation of methotrexate as soon as the diagnosis of neuro-BD is made [229]. Anti-TNFα drugs are indicated as second-line therapies by the international consensus recommendations of parenchymal neuro-BD, while the 2018 EULAR guidelines identify these drugs as useful for first-line treatment in aggressive neurological manifestations and in those cases with an inadequate response to moderate or higher doses of corticosteroids [230].

Case reports and cases series suggest infliximab as an effective and well-tolerated medication for new-onset and relapsing neuro-BD in association with corticosteroids and with or without different medications such as colchicine, azathioprine, or methotrexate [231, 232]. In an open-label, real-life clinical experience, 15 patients treated with infliximab showed no relapses or further disability accumulation, without differences among those who received infliximab as a single treatment and those who received infliximab in addition to other drugs [233].

An observational study including 17 patients with a severe and refractory neurological involvement treated with infliximab or adalimumab showed an overall improvement in 94.1% of the cases, and a complete response in a quarter of the patients, with a clear corticosteroid-sparing effect [234]. However, the effectiveness of infliximab without corticosteroids in the treatment of acute parenchymal neuro-BD has not been analyzed, and its effectiveness in preventing new acute attacks needs to be further explored [233]. Some concerns have also arisen about a potential risk for demyelinating events associated with TNF-α inhibitor use [235].

The use of cyclophosphamide can be considered a third-line option in neuro-BD, with data mostly obtained by single cases. Cyclophosphamide is a non-specific alkylating agent [236]. This potent immunosuppressant drug, mainly active on T and B lymphocyte proliferation, has been widely used in rheumatology for the treatment of severe vasculitis and lupus nephritis [237, 238]. Cyclophosphamide is equally efficacious given orally or intravenously, but the pulsed intravenous administration is considered to have less toxicity including leukopenia [239].

In a retrospective series, 38/40 patients treated for 2 years with high doses of intravenous cyclophosphamide (600 mg/m2 at the first, second, fourth, sixth, and eighth day, then every 2 months) initially associated with corticosteroids for severe neuro-BD obtained clinical improvement with good tolerance [240]. The effectiveness of this drug is burdened with high toxicity, and this limits its use in selected cases characterized by an aggressive course. Gurcan et al. in a retrospective study covering a median follow-up period of 25 years observed that among patients treated with cyclophosphamide, of which 70% had a vascular and neurological involvement, 9% developed short-term side effects, 30% experienced infertility, and 8% had malignancies [241].

A randomized, prospective, head-to-head phase III study (ITAC) comparing cyclophosphamide to infliximab for the treatment of severe BD, including patients aged ≥12 years with neurological involvement, is ongoing (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03371095). Interferon-α has been described in case reports and series (also including juvenile BD cases) as effective and well tolerated in refractory parenchymal neuro-BD [242, 243]. Rituximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody targeted against the membrane antigen CD20, and mycophenolate mofetil, an inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase inhibitor, both represent valid alternative drugs in parenchymal neuro-BD, even if larger studies are needed to confirm their role and their effectiveness [244,245,246]. Encouraging, although still limited reports have been published on tocilizumab, suggesting it as effective in severe and refractory parenchymal neuro-BD without serious adverse events [138, 247, 248].

Neuro-BD characterized by cerebral thrombophlebitis requires high doses of glucocorticoids, for a rapid remission, they can be first administered intravenously (methylprednisolone for 3 days) and then continued orally (prednisone 1 mg/kg/day) [75]. The association with an immunosuppressive agent such as an anti-TNF-α blocker, azathioprine, cyclosporine, or cyclophosphamide is useful in cases of relapse, but also when patients’ characteristics and clinical presentations require a more aggressive approach [226].

In contrast, anticoagulant therapy is controversial, suggested for a limited period, once the presence of additional prothrombotic risk factors has been assessed [75]. Heparin or low-molecular-weight heparinoids are then substituted with warfarin, and no clear indications about the precise duration of anticoagulation is available [249]. Cyclosporine A should be avoided in patients with an ongoing or previous neurologic involvement because of its potential neurotoxicity [250, 251].

5.6 Vascular Involvement

Vascular BD may range from venous to arterial to a combination of venous and arterial involvement and may represent a life-threatening condition. Vascular inflammation is the key element of thrombosis, playing a crucial role in recurrency; for this reason, immunosuppression represents the core of the treatment that includes corticosteroids and immunosuppressive drugs such as azathioprine and cyclosporine A [59]. Monoclonal anti-TNF-α drugs or cyclophosphamide can be preferred in severe conditions such as Budd–Chiari syndrome or peripheral arterial aneurysms/occlusions [59]. After induction, cyclophosphamide should be switched to azathioprine for maintenance therapy, as it is less toxic.

Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, mostly in association with other immunosuppressive agents, have emerged as effective in the management of major vessel involvement unresponsive to conventional immunosuppressants, and seem to reduce the risk of relapse after withdrawal [234, 252]. Tocilizumab has been recently suggested as a possible effective and well-tolerated alternative treatment in severe and/or refractory vascular BD [253]. Immunosuppressive treatment duration is still undefined, although an increased risk of relapse of vascular events is observed when not sufficiently prolonged [254].

In the presence of deep vein thrombosis, anticoagulants, once ruled out because of the risk of hemorrhage and the presence of possible aneurysms, may be added [59]. The role of anticoagulation in the long-term prevention of vascular recurrences, thrombus progression, and pulmonary embolism is still debated [254,255,256]. However, anticoagulation may represent a risk for pulmonary arterial aneurysms [254, 257]. Surgical procedures should be limited to selected cases and preceded by pharmacological treatment able to control the inflammation, owing to the high risk of post-operative complications [258].

5.7 Articular Involvement

In the presence of a limited number of inflamed joints, especially large joints, intra-articular corticosteroid injections may represent the first treatment choice. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug cycles can be helpful. Colchicine also offers a good response for the management of longer lasting, non-erosive arthritis [59]. Methotrexate, TNF-α inhibitors, and azathioprine may also exert beneficial effects in resistant, more aggressive articular involvement, in contrast to tocilizumab, which was only partially useful [59, 139].

In a multi-center retrospective study involving 15 patients with oral and genital ulcers and articular manifestations who did not tolerate or were resistant to other treatments (colchicine, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, and at least one anti-TNFα agent), secukinumab appeared to be safe and effective, especially in those patients treated with a dosage of 300 mg/month compared with those treated with 150 mg/month [132].

6 Conclusions

Behçet’s disease is a multi-system inflammatory disease with a relapsing-remitting course that in up to a quarter of the cases begins in the pediatric age group. Clinical features are similar to those observed in adults but may require years to clearly express, potentially delaying the final diagnosis.

Oral and genital ulcers are among the first manifestations to develop and may significantly compromise the quality of life, while ocular, GI, neurologic, and large-vessel involvement primarily weighs on morbidity and mortality. Because BD is a heterogeneous multi-systemic disease with a variable severity, its treatment requires a patient-centered strategy and a multi-disciplinary approach. As a long-term disease is expected, attention to a sparing use of corticosteroids, preventive measures, and lifestyle advice is required.

Old systemic therapies, such as corticosteroids and classic immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive agents, still represent valid options in different circumstances especially in those with mucocutaneus and articular involvement. A growing number of pharmacological trials is expanding the therapeutic possibilities, although only about one-seventh involve pediatric patients. Anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies have achieved a prominent place mostly in the treatment of ocular and GI diseases, but also representing a good alternative for the treatment of neurologic disease and severe mucocutaneous and articular manifestations.

Different new target molecules have emerged including anti-IL-6, anti-IL-1, anti-IL-17, small molecules, and IFN-α. Unfortunately, in the pediatric population, most of the treatments derive from experience in adults and are used off label. This highlights the urgent need for clinical trials involving young patients and evidence-based recommendations for children.

References

Hatemi G, Seyahi E, Fresko I, Talarico R, Uçar D, Hamuryudan V. Behçet’s syndrome: one year in review 2022. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2022;2:2.

Sota J, Rigante D, Lopalco G, Emmi G, Gentileschi S, Gaggiano C, et al. Clinical profile and evolution of patients with juvenile-onset Behçet’s syndrome over a 25-year period: insights from the AIDA network. Intern Emerg Med. 2021;16:2163–71.

Baş Y, Seçkin HY, Kalkan G, Takcı Z, Önder Y, Çıtıl R, et al. Investigation of Behçet’s disease and recurrent aphthous stomatitis frequency: the highest prevalence in Turkey. Balk Med J. 2016;33:390–5.

Calamia KT, Wilson FC, Icen M, Crowson CS, Gabriel SE, Kremers HM. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of Behçet’s disease in the US: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:600–4.

Ndiaye M, Sow AS, Valiollah A, Diallo M, Diop A, Alaoui RA, et al. Behçet’s disease in black skin: a retrospective study of 50 cases in Dakar. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2015;9:98–102.

Davatchi F, Shahram F, Chams-Davatchi C, Shams H, Nadji A, Akhlaghi M, et al. Behcet’s disease: from east to west. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29:823–33.

Olivieri I, Leccese P, Padula A, Nigro A, Palazzi C, Gilio M, et al. High prevalence of Behçet’s disease in southern Italy. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2013;31:28–31.

Mahr A, Belarbi L, Wechsler B, Jeanneret D, Dhote R, Fain O, et al. Population-based prevalence study of Behçet’s disease: differences by ethnic origin and low variation by age at immigration. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3951–9.

Mohammad A, Mandl T, Sturfelt G, Segelmark M. Incidence, prevalence and clinical characteristics of Behcet’s disease in southern Sweden. Rheumatology. 2013;52:304–10.

Kötter I, Vonthein R, Müller CA, Günaydin I, Zierhut M, Stübiger N. Behçet’s disease in patients of German and Turkish origin living in Germany: a comparative analysis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:133–9.

Pain CE. Juvenile-onset Behçet’s syndrome and mimics. Clin Immunol. 2020;214: 108381.

Gül A. Pathogenesis of Behçet’s disease: autoinflammatory features and beyond. Semin Immunopathol. 2015;37:413–8.

Barnes CG, Yazici H. Behçet’s syndrome. Rheumatology. 1999;38:1171–4.

Maldini C, LaValley MP, Cheminant M, de Menthon M, Mahr A. Relationships of HLA-B51 or B5 genotype with Behçet’s disease clinical characteristics: systematic review and meta-analyses of observational studies. Rheumatology. 2012;51:887–900.

Filleron A, Tran TA, Hubert A, Letierce A, Churlaud G, Koné-Paut I, et al. Regulatory T cell/Th17 balance in the pathogenesis of paediatric Behçet disease. Rheumatology. 2021;61:422–9.

Remmers EF, Cosan F, Kirino Y, Ombrello MJ, Abaci N, Satorius C, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants in the MHC class I, IL10, and IL23R-IL12RB2 regions associated with Behçet’s disease. Nat Genet. 2010;42:698–702.

Mizuki N, Meguro A, Ota M, Ohno S, Shiota T, Kawagoe T, et al. Genome-wide association studies identify IL23R-IL12RB2 and IL10 as Behçet’s disease susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2010;42:703–6.

Seoudi N, Bergmeier LA, Drobniewski F, Paster B, Fortune F. The oral mucosal and salivary microbial community of Behçet’s syndrome and recurrent aphthous stomatitis. J Oral Microbiol. 2015;7:27150.

Shimizu J, Kubota T, Takada E, Takai K, Fujiwara N, Arimitsu N, et al. Bifidobacteria abundance-featured gut microbiota compositional change in patients with Behcet’s disease. PLoS ONE. 2016;11: e0153746.

Krause I, Yankevich A, Fraser A, Rosner I, Mader R, Zisman D, et al. Prevalence and clinical aspects of Behcet’s disease in the north of Israel. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:555–60.

Koné-Paut I. Behçet’s disease in children, an overview. Pediatr Rheumatol. 2016;14:10.

Karincaoglu Y, Borlu M, Toker SC, Akman A, Onder M, Gunasti S, et al. Demographic and clinical properties of juvenile-onset Behçet’s disease: a controlled multicenter study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:579–84.

Yazici H, Ugurlu S, Seyahi E. Behçet syndrome: is it one condition? Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2012;43:275–80.

Yazici H, Seyahi E, Hatemi G, Yazici Y. Behçet syndrome: a contemporary view. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2018;14:107–19.

Bettiol A, Prisco D, Emmi G. Behçet: the syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59:101–7.

Seyahi E. Phenotypes in Behçet’s syndrome. Intern Emerg Med. 2019;14:677–89.

McHugh J. Different phenotypes identified for Behçet syndrome. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2021;17:188.

Zou J, Luo JF, Shen Y, Cai JF, Guan JL. Cluster analysis of phenotypes of patients with Behçet’s syndrome: a large cohort study from a referral center in China. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021;23:45.

Soejima Y, Kirino Y, Takeno M, Kurosawa M, Takeuchi M, Yoshimi R, et al. Changes in the proportion of clinical clusters contribute to the phenotypic evolution of Behçet’s disease in Japan. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021;23:49.

Koné-Paut I, Shahram F, Darce-Bello M, Cantarini L, Cimaz R, Gattorno M, et al. Consensus classification criteria for paediatric Behçet’s disease from a prospective observational cohort: PEDBD. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:958–64.

Atmaca L, Boyvat A, Yalçındağ FN, Atmaca-Sonmez P, Gurler A. Behçet disease in children. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2011;19:103–7.

Koné-Paut I, Darce-Bello M, Shahram F, Gattorno M, Cimaz R, Ozen S, et al. Registries in rheumatological and musculoskeletal conditions. Paediatric Behçet’s disease: an international cohort study of 110 patients One-year follow-up data. Rheumatology. 2011;50:184–8.

Nanthapisal S, Klein NJ, Ambrose N, Eleftheriou D, Brogan PA. Paediatric Behçet’s disease: a UK tertiary centre experience. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:2509–16.

Gallizzi R, Pidone C, Cantarini L, Finetti M, Cattalini M, Filocamo G, et al. A national cohort study on pediatric Behçet’s disease: cross-sectional data from an Italian registry. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2017;15:84.

ButbulAviel Y, Batu ED, Sözeri B, Aktay Ayaz N, Baba L, Amarilyo G, et al. Characteristics of pediatric Behçet’s disease in Turkey and Israel: a cross-sectional cohort comparison. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2020;50:515–20.

Tugal-Tutkun I. Behçet’s uveitis. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2009;16:219–24.

Citirik M, Berker N, Songur MS, Soykan E, Zilelioglu O. Ocular findings in childhood-onset Behçet disease. J AAPOS. 2009;13:391–5.

Ksiaa I, Abroug N, Kechida M, Zina S, Jelliti B, Khochtali S, et al. Eye and Behçet’s disease. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2019;42:e133–46.

Mendes D, Correia M, Barbedo M, Vaio T, Mota M, Gonçalves O, et al. Behçet’s disease: a contemporary review. J Autoimmun. 2009;32:178–88.

Kitaichi N, Miyazaki A, Stanford MR, Iwata D, Chams H, Ohno S. Low prevalence of juvenile-onset Behcet’s disease with uveitis in East/South Asian people. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93:1428–30.

Yıldız M, Köker O, Adrovic A, Şahin S, Barut K, Kasapçopur Ö. Pediatric Behçet’s disease: clinical aspects and current concepts. Eur J Rheumatol. 2019;7(1):1–10.

Krupa B, Cimaz R, Ozen S, Fischbach M, Cochat P, Isabelle K-P. Pediatric Behcet’s disease and thromboses. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:387–90.

Shahram F, Nadji A, Akhlaghi M, Faezi ST, Chams-Davatchi C, Shams H, et al. Paediatric Behçet’s disease in Iran: report of 204 cases. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2018;36:135–40.

Bulur I, Onder M. Behçet disease: new aspects. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:421–34.

Calamia KT, Schirmer M, Melikoglu M. Major vessel involvement in Behçet’s disease: an update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23:24–31.

Yazici H, Tüzün Y, Pazarli H, Yurdakul S, Ozyazgan Y, Ozdoğan H, et al. Influence of age of onset and patient’s sex on the prevalence and severity of manifestations of Behçet’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 1984;43:783–9.

Mora P, Menozzi C, Orsoni JG, Rubino P, Ruffini L, Carta A. Neuro-Behçet’s disease in childhood: a focus on the neuro-ophthalmological features. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:18.

Uluduz D, Kürtüncü M, Yapıcı Z, Seyahi E, Kasapçopur Ö, Özdoğan H, et al. Clinical characteristics of pediatric-onset neuro-Behçet disease. Neurology. 2011;77:1900–5.

Hu YC, Chiang BL, Yang YH. Clinical manifestations and management of pediatric Behçet’s disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2021;61:171–80.

Grigg EL, Kane S, Katz S. Mimicry and deception in inflammatory bowel disease and intestinal behçet disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;8:103–12.

Choi IJ, Kim JS, Cha SD, Jung HC, Park JG, Song IS, et al. Long-term clinical course and prognostic factors in intestinal Behçet’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:692–700.

Kim JS, Lim SH, Choi IJ, Moon H, Jung HC, Song IS, et al. Prediction of the clinical course of Behçet’s colitis according to macroscopic classification by colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2000;32:635–40.

Lee CR, Kim WH, Cho YS, Kim MH, Kim JH, Park IS, et al. Colonoscopic findings in intestinal Behçet’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001;7:243–9.

Gallizzi R, De Vivo D, Valenti S, Pidone C, Romeo C, Caruso R, et al. Intestinal and neurological involvement in Behcet disease: a clinical case. Ital J Pediatr. 2017;43:33.

Yildiz M, Haslak F, Adrovic A, Sahin S, Koker O, Barut K, et al. Pediatric Behçet’s disease. Front Med. 2021;8: 627192.

Manthiram K, Preite S, Dedeoglu F, Demir S, Ozen S, Edwards KM, et al. Common genetic susceptibility loci link PFAPA syndrome, Behçet’s disease, and recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117:14405–11.

Pak S, Logemann S, Dee C, Fershko A. Breaking the magic: mouth and genital ulcers with inflamed cartilage syndrome. Cureus. 2017;9(10): e1743.

Lee SK, Kim BK, Kim TI, Kim WH. Differential diagnosis of intestinal Behçet’s disease and Crohn’s disease by colonoscopic findings. Endoscopy. 2009;41:9–16.

Hatemi G, Christensen R, Bang D, Bodaghi B, Celik AF, Fortune F, et al. 2018 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of Behçet’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:808–18.

Papadopoulou C, Omoyinmi E, Standing A, Pain CE, Booth C, D’Arco F, et al. Monogenic mimics of Behçet’s disease in the young. Rheumatology. 2019;58:1227–38.

Zhou Q, Wang H, Schwartz DM, Stoffels M, Park YH, Zhang Y, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in TNFAIP3 leading to A20 haploinsufficiency cause an early-onset autoinflammatory disease. Nat Genet. 2016;48:67–73.

Kul Cinar O, Romano M, Guzel F, Brogan PA, Demirkaya E. Paediatric Behçet’s disease: a comprehensive review with an emphasis on monogenic mimics. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1278.

Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet’s disease. International study group for Behçet’s disease. Lancet. 1990;335:1078–80.

Davatchi F, Assaad-Khalil S, Calamia KT, Crook JE, Sadeghi-Abdollahi B, et al. The International Criteria for Behçet’s Disease (ICBD): a collaborative study of 27 countries on the sensitivity and specificity of the new criteria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:338–47.

Batu ED, Sönmez HE, Sözeri B, ButbulAviel Y, Bilginer Y, Özen S. The performance of different classification criteria in paediatric Behçet’s disease. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017;35(Suppl. 108):119–23.

Batu ED. Diagnostic/classification criteria in pediatric Behçet’s disease. Rheumatol Int. 2019;39(1):37–46.

Gheita TA, El-Latif EA, El-Gazzar II, Samy N, Hammam N, Abdel Noor RA, et al. Behçet’s disease in Egypt: a multicenter nationwide study on 1526 adult patients and review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38:2565–75.

Treudler R, Orfanos CE, Zouboulis CC. Twenty-eight cases of juvenile-onset Adamantiades-Behçet disease in Germany. Dermatology. 1999;199:15–9.

Borlu M, Ukşal U, Ferahbaş A, Evereklioglu C. Clinical features of Behçet’s disease in children. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:713–6.

Hamzaoui A, Jaziri F, Ben Salem T, Ghorbel SIB, et al. Comparison of clinical features of Behcet disease according to age in a Tunisian cohort. Acta Med Iran. 2014;52:748–51.

Alpsoy E, Donmez L, Onder M, Gunasti S, Usta A, Karincaoglu Y, et al. Clinical features and natural course of Behçet’s disease in 661 cases: a multicentre study. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:901–6.

Saadoun D, Wechsler B, Desseaux K, Le Thi HD, Amoura Z, Resche-Rigon M, et al. Mortality in Behçet’s disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2806–12.

Koné-Paut I, Yurdakul S, Bahabri SA, Shafae N, Ozen S, Ozdogan H, et al. Clinical features of Behçet’s disease in children: an international collaborative study of 86 cases. J Pediatr. 1998;132:721–5.

Nakamura K, Iwata Y, Asai J, Kawakami T, Tsunemi Y, Takeuchi M, Mizuki N, Kaneko F; Members of the Consensus Conference on Treatment of Skin and Mucosal Lesions (Committee of Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Mucocutaneous Lesions of Behçet's disease) Guidelines for the treatment of skin and mucosal lesions in Behçet's disease: a secondary publication. J Dermatol. 2020;47(3):223–35

Kone-Paut I, Barete S, Bodaghi B, Deiva K, Desbois AC, et al. French recommendations for the management of Behçet’s disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16:352.

Tse HN, Borrow R, Arkwright PD. Immune response and safety of viral vaccines in children with autoimmune diseases on immune modulatory drug therapy. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2020;19:1115–27.

Heijstek MW, de Ott Bruin LM, Bijl M, Borrow R, van der Klis F, Koné-Paut I, et al. EULAR recommendations for vaccination in paediatric patients with rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1704–12.