Abstract

Background

The nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) signalling pathway is a regulator of immune response and inflammation that has been implicated in the carcinogenic process. We examined differentially expressed genes in this pathway and miRNAs to determine associations with colorectal cancer (CRC).

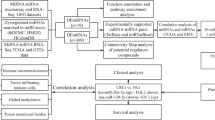

Methods

We used data from 217 CRC cases to evaluate differences in NF-κB signalling pathway gene expression between paired carcinoma and normal mucosa and identify miRNAs that are associated with these genes. Gene expression data from RNA-Seq and miRNA expression data from Agilent Human miRNA Microarray V19.0 were analysed. We evaluated genes most strongly associated and differentially expressed (fold change (FC) of > 1.5 or < 0.67) that were statistically significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Results

Of the 92 genes evaluated, 22 were significantly downregulated and nine genes were significantly upregulated in all tumours. Two additional genes (CD14 and CSNK2A1) were dysregulated in MSS tumours and two genes (CARD11 and VCAM1) were downregulated and six genes were upregulated (LYN, TICAM2, ICAM1, IL1B, CCL4 and PTGS2) in MSI tumours. Sixteen of the 21 dysregulated genes were associated with 40 miRNAs. There were 76 miRNA:mRNA associations of which 38 had seed-region matches. Genes were associated with multiple miRNAs, with TNFSRF11A (RANK) being associated with 15 miRNAs. Likewise several miRNAs were associated with multiple genes (miR-150-5p with eight genes, miR-195-5p with four genes, miR-203a with five genes, miR-20b-5p with four genes, miR-650 with six genes and miR-92a-3p with five genes).

Conclusions

Focusing on the genes and their associated miRNAs within the entire signalling pathway provides a comprehensive understanding of this complex pathway as it relates to CRC and offers insight into potential therapeutic agents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) signalling pathway is a key regulator of inflammation and has been associated with carcinogenesis (Merga et al. 2016). The NF-κB family comprised five hetero or homodimers: RelA (p65), RelB, NF-κB1 (p50 and its precursor p105), NF-κB2 (p52 and its precursor p100), and c-Rel (Pereira and Oakley 2008). In an inactive state, NF-κB dimers are bound to inhibitors of NF-κB (IκB) [such as inhibitory κB kinases (IKK) or their inactive precursors (i.e. p105 and p100)]. The classical or canonical NF-κB signalling pathway is activated by cytokines, such as IL-1 and TNF, T-cell receptors (TCR), or B-cell receptors (BCR) which stimulate the IKK complex, phosphorylating p105 which releases the NF-κB dimers to the nucleus where they activate gene expression. Three IKKs, IKKα, IKKβ and IKKγ or NEMO (NF-κB essential modulator), are involved in the canonical pathway. The alternative pathway (non-canonical pathway) originates through B-cell activation factor (BAFF-R), lymphotoxin β-receptor (LTβR), CF40 receptor activator for nuclear factor-kappa B (RANK), and TNFR2, which in turn activate adaptor protein NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK) which activates IKKα. IKKα activity induces phosphorylation of RelB and p100. It has been proposed that the canonical pathway is associated with an acute phase response and is integrated with the non-canonical pathway for a more sustained immunological response (Merga et al. 2016). In colon cancer specifically, IKKB-induced NF-κB activation in intestinal epithelial cells and its corresponding inflammation appears to have an essential role in tumour formation (Slattery and Fitzpatrick 2009).

NF-κB is a transcription factor which, when activated can regulate over 200 genes involved in inflammation and cell function and survival (Pereira and Oakley 2008). MiRNAs, small non-coding RNAs that bind to the 3′UTR of the protein-coding mRNAs and inhibit their translation, may also be transcriptional targets. This dynamic provides a mechanism for dysregulation of genes through the activation of transcription factors such as NF-κB (Hoesel and Schmid 2013). Several miRNAs, including let-7, miR-9, miR-21, miR-143, miR-146 and miR-224, are transcriptional targets of NF-κB (Hoesel and Schmid 2013). These miRNAs have been shown to be involved in feedback mechanisms that influence the NF-κB signalling pathway by either targeting upstream signalling molecules or members of the NF-κB family. Let-7 has been shown to target IL-6 in that a reduction in Let-7 results in higher levels of IL-6 and activation of NF-κB in a positive feedback loop (Iliopoulos et al. 2009). It has been suggested that miR-520e may modify cell proliferation by targeting NIK (Zhang et al. 2012). Other studies have shown that miR-15a, miR-16 and miR-223 can influence IKKα protein expression (Li et al. 2010). While these data support the co-regulatory functions of NF-κB and miRNAs, there has not been a systematic evaluation of the NF-κB signalling pathway as it relates to miRNAs.

There is strong evidence to suggest that inflammation is a key element in the etiology of colorectal cancer (CRC) [reviewed in (Slattery and Fitzpatrick 2009)]. In this paper we examine expression levels of 92 genes in the NF-κB signalling pathway. We focus on genes within this signalling pathway that are dysregulated, in that the expression levels in the tumours are statistically different than in normal mucosa with a fold change (FC) of difference that is > 1.50 or < 0.67. We examine differential expression of miRNAs with dysregulated pathway genes. Our aim is to broaden our understanding of the NF-κB signalling pathway as it relates to CRC.

Methods

Study participants

Study participants come from two population-based case–control studies that included all incident colon and rectal cancer patients diagnosed between 30 and 79 years of age in Utah or who were members of Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC). Participants were non-Hispanic white, Hispanic or black for the colon cancer study; the rectal cancer study also included people of Asian race (Slattery et al. 1997, 2003). Cases were verified by tumour registry as a first primary adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum, diagnosed between October 1991 and September 1994 (colon study) and between May 1997 and May 2001 (rectal study) (Slattery et al. 2016). The Institutional Review Boards at the University of Utah and at KPNC approved the study.

RNA processing

Methods for RNA processing and mRNA and miRNA analysis have been previously described and are summarised here (Slattery et al. 2017a, b). Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue from the initial biopsy or surgery was used to extract RNA. RNA was extracted, isolated and purified from carcinoma tissue and adjacent normal mucosa as previously described (Slattery et al. 2015). We observed no differences in RNA quality based on age of the tissue.

mRNA:RNA-seq sequencing library preparation and data processing

Total RNA from 245 colorectal carcinoma and normal mucosa pairs was chosen for sequencing based on availability of RNA and high quality miRNA data in order to have both mRNA and miRNA from the same individuals; the 217 pairs that passed quality control (QC) were used in these analyses (Pellatt et al. 2016a, b). RNA library construction was performed with the Illumina TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Sample Preparation Kit with Ribo-Zero. The samples were then fragmented and primed for cDNA synthesis, adapters were then ligated onto the cDNA and the resulting samples were then amplified using PCR; the amplified library was then purified using Agencourt AMPure XP beads. A more detailed description of the methods can be found in our previous work (Slattery et al. 2015a, b). Illumina TruSeq v3 single-read flow cell and a 50 cycle single-read sequence run were performed on an Illumina HiSeq instrument. Reads were aligned to a sequence database containing the human genome (build GRCh37/hg19, February 2009 from genome.ucsc.edu) and alignment was performed using novoalign v2.08.01. Total gene counts were calculated for each exon and UTR of the genes using gene coordinates obtained from http://genome.ucsc.edu. Genes that were not expressed in our RNA-Seq data or for which the expression was missing for the majority of samples were excluded from further analysis (Slattery et al. 2015a, b).

miRNA

The Agilent Human miRNA Microarray V19.0 was used. Data were required to pass QC parameters established by Agilent that included tests for excessive background fluorescence, excessive variation among probe sequence replicates on the array, and measures of the total gene signal on the array to assess low signal. Samples failing to meet quality standards were relabelled, hybridised to arrays and re-scanned. If a sample failed QC assessment a second time, the sample was excluded from analysis. The repeatability associated with this microarray was extremely high (r = 0.98) (Slattery et al. 2016); comparison of miRNA expression levels obtained from the Agilent microarray to those obtained from qPCR had an agreement of 100% in terms of directionality of findings and the FCs were almost identical (Pellatt et al. 2016). To normalise differences in miRNA expression that could be attributed to the array, amount of RNA, location on array, or factors that could erroneously influence miRNA expression levels, total gene signal was normalised by multiplying each sample by a scaling factor which was the median of the 75th percentiles of all the samples divided by the individual 75th percentile of each sample (Agilent GeneSpring User Manual).

NF-κB signalling genes

The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (http://www.genome.jp/kegg-gin/show_pathway?hsa04064) Pathway map for NF-Kappa B Signalling was used to identify genes. We identified 95 genes (Supplemental Table 1) in this signalling pathway; 92 of these genes had sufficient expression in our CRC tissue for further analysis.

Statistical methods

We utilised negative binomial mixed effects model in SAS (accounting for carcinoma/normal status as well as subject effect) to determine which genes in the NF-κB signalling pathway had a significant difference in expression between individually paired CRC and normal mucosa and their related fold changes (FC). In the negative binomial model we offset the overall exposure as the log of the expression of all identified protein-coding genes (n = 17,461). The Benjamini and Hochberg (Benjamini 1995) procedure was used to control the false discovery rate (FDR) using a value of < 0.05. A FC greater than one indicates a positive differential expression (i.e. upregulated in carcinoma tissue) while a FC between zero and one indicates a negative differential expression (i.e. downregulated in carcinoma tissue). We calculated the level of expression of each gene by dividing the total expression for that gene in an individual by the total expression of all protein-coding genes per million transcripts (RPMPCG or reads per million protein-coding genes). We considered overall CRC differential expression as well as differential expression for microsatellite unstable (MSI) and stable (MSS) tumours separately.

We arbitrarily focused on those genes and miRNAs with FCs of > 1.50 or < 0.67 in order to have more meaningful biological differences between carcinoma and normal samples. There were 814 miRNAs expressed in greater than 20% of normal colorectal mucosa samples that were analysed; differential expression was calculated using subject-level paired data as the expression in the carcinoma tissue minus the expression in the normal mucosa. In these analyses, we fit a least squares linear regression model to the RPMPCG differential expression levels and miRNA differential expression levels. P-values were generated using the bootstrap method by creating a distribution of 10,000 F statistics derived by resampling the residuals from the null hypothesis model of no association between gene expression and miRNA expression using the boot package in R. Linear models were adjusted for age and sex. Multiplicity adjustments for mRNA:miRNA associations were made at the gene level using the FDR by Benjamini and Hochberg (Benjamini 1995).

Bioinformatics analysis

We analysed miRNAs and targeted mRNAs for seed-region matches. The mRNA 3′ UTR FASTA as well as the seed-region sequence of the associated miRNA were analysed to determine seed-region pairings between miRNA and mRNA. MiRNA seed regions were calculated as described in our previous work (Mullany et al. 2016); we calculated and included seeds of six, seven and eight nucleotides in length. Our hypothesis is that a seed match would increase the likelihood that identified genes associated with a specific miRNA were more likely to have a direct association given a higher propensity for binding. As miRTarBase (Chou et al. 2016) uses findings from many different investigations spanning across years and alignments, we used FASTA sequences generated from both GRCh37 and GRCh38 Homo sapiens alignments, using UCSC Table browser (https://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgTables) (Karolchik et al. 2004). We downloaded FASTA sequences that matched our Ensembl IDs and had a consensus coding sequences (CCDS) available. Analysis was done using scripts in R 3.2.3 and in perl 5.018002.

Results

The majority of cases were located in the colon (77.9%) rather than the rectum (22.1%) (Table 1).

The mean age of the study population was 64.8 years and 54.4% of the population were male. Non-Hispanic white cases were the predominate race (74.2%) followed by Hispanic (6.5%) and Black (3.7%). The majority of tumours (86.6%) were considered microsatellite stable while 13.4% had MSI.

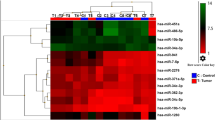

Twenty-two genes were significantly downregulated when considering a FC of < 0.67 and nine genes were significantly upregulated with a FC of > 1.50 (Table 2).

Specific to MSS tumours, CD14 had a FC of 0.66 compared to a FC of 0.68 overall and CSNK2A1 had a FC of 1.54 for MSS tumours compared to 1.49 overall (Supplemental Table 2 for MSS results). Evaluation of MSI-specific tumours showed that two additional genes were downregulated, CARD11 and VCAM1 (FC 0.37 and 0.59, respectively) and six genes were upregulated (LYN FC 1.59, TICAM2 FC 1.64, ICAM1 FC 1.91, IL1B FC 2.06, CCL4 FC 2.72, and PTGS2 FC 3.23) that were statistically significant (Supplemental Table 3 for MSI-specific results). Among the most downregulated genes were CCL13 (FC 0.11), CCL19 (FC 0.14), PRKCB (FC 0.28, TNFRSF13C (FC0.29), and CD40LG (FC0.30). Seven genes were upregulated with a FC greater than 2.0 (CSNK2A2 FC 2.02, CSNK2A1P FC 2.17, IRAK1 FC 2.24, BCL2L1 FC 2.25, PLAU FC 2.52, CXCL2 FC 2.55, and IL8 FC 5.12). Figure 1 shows the location of these genes in the NF-κB signalling pathway.

Sixteen of the dysregulated genes were associated with 40 miRNAs (Table 3).

Of the total 76 miRNA:mRNA associations from these 16 genes and 40 miRNAs, 38 had seed-region matches and 19 of these matches showed an inverse association between the differential expression of the miRNA and the differential expression of the mRNA. TNFRSF11A was associated with the greatest number of miRNAs (N = 15). PLCG1 was associated with 12 miRNAs, TRAF5 with eight miRNAs, CXCL12 with six miRNAs, and CCL21 and PLCG2 each with five miRNAs. The miRNA and mRNA associations are further summarised in Table 4.

The miRNAs with the greatest number of genes associated with these were miR-150-5p with eight genes (five with a seed-region match), miR-195-5p with four genes (two with a seed-region match), miR-203a with five genes (four with a seed-region match), miR-20b-5p with four genes (four with a seed-region match), miR-650 with six genes (one with a seed-region match), and miR-92a-3p with five genes (no seed-region matches). Interestingly, the six genes associated with miR-650 also were associated with miR-150-5p. The miRNA associations with dysregulated genes can be seen in Fig. 1.

Discussion

The NF-κB signalling pathway is important in the carcinogenic process given its role in the regulation of genes both inside and outside of the immune system. Thus, it can potentially influence many diseases, including CRC. Our data suggest that 44.5% of NF-κB signalling pathway genes were dysregulated in colorectal carcinoma relative to expression in adjacent normal mucosa, when considering all carcinomas as well as MSS and MSI-specific carcinomas and greater levels of FC. Sixteen of these dysregulated genes were associated with 40 miRNAs. Approximately half of the 76 mRNA:miRNA associations had seed-region matches. Focusing on the genes and their associated miRNAs within the signalling pathway allows us to obtain a better understanding of how this complex pathway operates.

NF-κB activation can be involved in immune defense, especially in acute inflammatory response; it also can have be pro-inflammatory involved in pro-tumourigenic functions on the other (Hoesel and Schmid 2013). We observed dysregulated genes in both the canonical and non-canonical components of the NF-κB signalling pathway in genes suggesting both immune defense and a pro-inflammatory response. Our data showed that in the canonical pathway, the majority of genes that were downregulated were upstream of IKK and NF-κB1 while upregulated genes were mainly downstream of these central genes. Genes needed for T-cell signal transduction, ZAP70 and LAT (linker for activation of T-cells) were downregulated and PLCG1 was upregulated in the TCR arm of the pathway. Studies have shown that higher levels of PLCG1 expression in breast tumours has been linked to metastasis (Sala et al. 2008). BLNK, Btk, PRKCB and PLCG2, critical for BCR signalling, were downregulated. Since Btk plays an important role in adaptive immunity and mutations in PLCG2 have been associated with immune deficiency, downregulation of these genes could have a negative impact on immune response. IL1R, which is an antagonist to the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL1, was downregulated while the interleukin receptor kinase 1 (IRAK1) which could positively induce IKK was upregulated. TRAF5, downstream from TNF-R1, which is a positive regulator of IKK and NF-κB, was upregulated. These alterations in gene expression could influence immune response and promote inflammation by downregulation of genes that enable immune response and upregulation of pro-inflammatory genes.

Interestingly, NEMO (IKBKγ) (FC 1.11), IKBKB (FC 0.94), NFκB1 (FC 0.92) and RELA (FC 1.12) were only slightly changed in carcinoma tissue compared to normal mucosa. Given that NF-κB is a transcription factor, it is possible that its expression is more tightly controlled through feedback loops. However, once the system is activated by dysregulated upstream genes, an active NF-κB can stimulate expression of downstream genes. Downstream of the IKK and NF-κB, several major genes were upregulated, including BCL21, IL8 (CXCL8) and CXCL2 (MIP-2 in pathway). BLC2 (which was downregulated) and BCL2L1 are anti-apoptotic; IL8 and CXCL2 are chemokines that are pro-inflammatory and enhance the proliferation and survival of cancer cells (Waugh and Wilson 2008).

Activators of the non-canonical NF-κB signalling pathway were for the most part downregulated. These included CD40LG, CD40, RANK (TNFSF11A), LTA (TNFSF1) LTB (TNFSF3), LIGHT (TNFSF14), BAFF-R (B-cell activating receptor coded by TNFSF13) which are all part of the TNF super family and key regulators of immune response. Likewise NIK (MAP3K14) was also downregulated and is the major intermediary molecule to IKK and NFKB2 activation. Three downstream genes of NIK, CCL13, CCL19 and CCL21, were downregulated; these genes are part of a family of CC cytokines and play a role in inflammatory response and normal lymphocyte recirculating.

Several miRNAs have been linked to genes within the NF-κB signalling pathway (Ma et al. 2011). Many of the miRNAs previously studied that have been targeted with NF-κB signalling, such as miR-21, have been linked to both immune response and inflammation (Mima et al. 2016; Schetter et al. 2009), have been shown to be mediated by NF-κB in response to oxidative stress (Wei et al. 2014), or have been associated with specific cancers such as gastric cancer (Sha et al. 2014). In this study, we only evaluated miRNAs with genes that had a more meaningful level of change in expression in carcinoma relative to normal mucosa. Likewise, our analysis focused on CRC tissue and findings from other tissue sources may not be relevant for CRC. We did not observe miR-21 to be associated with any of the dysregulated genes evaluated after adjustment for multiple comparisons. Other miRNAs associated with inflammation and immune response (Contreras and Rao 2012) that have been linked to the NF-κB pathway for which we did not observe an association in this study were: miR-181b, previously associated with CYLD, which has a negative regulator effect on NF-κB; miR-301a, which has previously been shown to indirectly activate NF-κB via downregulation of NF-κB repressing factor (NKBF); miR-155, previously associated with BCR-related genes and the expression of IL8 (Ma et al. 2011). It also has been suggested that miR-15a, miR-16 and miR-223, which are important in innate immune cells, may be important in the non-canonical NF-κB pathway (Li et al. 2010); we did not observe any meaningful associations between these miRNAs and pathway genes. However, miR-146a which has been shown to be associated with IRAK1 and TRAF6 and upregulated by IL-1β and TNF (Hill et al. 2015) was upregulated in our data when TRAF5 (tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated 5) also was significantly upregulated. MiR-199 has previously been associated with IKKB (Contreras and Rao 2012); we observed an association with a seed-region match between TNFRSF11A (RANK) and miR-199a-5p. Likewise, miR-221 has been reported as being associated with TNFα (Contreras and Rao 2012); miR-221-3p was associated with CCL13 in the non-canonical NF-κB pathway in our data. TRAF5 has been associated with miR-26b in melanoma cells (Li et al. 2016a, b). While we observed eight miRNAs associated with TRAF5, we did not observe an association with miR-26b in CRC tissue. MiR-503 has been shown to target RANK in osteoclastogenesis (Chen et al. 2014). TNFRSF11A (i.e. RANK) was associated with 15 miRNAs in our data, although not associated with miR-503. Other miRNAs, including let-7, miR-9, miR-143 and miR-224 that have been shown to be transcriptional targets of NF-κB (Hoesel and Schmid 2013) were not associated with genes evaluated in our colorectal data. Lack of confirmation of previous findings could be the result of our larger study with more power. Additionally since many studies have examined few miRNAs whereas we examined hundreds, differences in observed associations could be from our adjustment for multiple comparisons.

We identified several miRNAs that appear to be important with dysregulated genes in the NF-κB signalling pathway; many of these miRNAs were associated with multiple genes that further suggest their importance in the pathway in CRC. MiR-150-5p was associated with eight genes and had seed-region matches with five of these genes. MiR-150 has previously been associated with immune response (Tsitsiou and Lindsay 2009), with reducing inflammatory cytokine production (Sang et al. 2016), and was one of 25 miRNAs that were important in distinguishing rectal carcinomas from normal rectal mucosa in our data (Pellatt et al. 2016). Interestingly, six of these eight miRNAs associated with miR-150-5p were also associated with miR-650. Both miR-203a and miR-20b-5p had seed-region matches with four genes in our data while miR-92a-3p was associated with five genes, although none with a seed-region match. Both miR-20b-5p and miR-92a-3p are members of the miR-17-92 cluster, which has been associated with CRC and MYC expression and Wnt signalling (Li et al. 2014, 2016; Ma et al. 2016).

Several pathway genes were associated with numerous miRNAs. Some of these associations had seed-region matches which implied a greater likelihood of binding that could alter expression. Seed-region matches for pairs that were inversely associated in that either the mRNA or miRNA was upregulated while the other was downregulated, suggest binding that has a greater likelihood of directly altering function. However, miRNA:mRNA associations that had the same directionality in terms of FC, suggest an indirect effect or a feedback loop that results in both miRNA and mRNA being either up or downregulated. TRAF5 was associated with eight miRNAs (direct seed-region matches with two miRNAs); PLCG1 was associated with 12 miRNAs (six with seed-region matches and one, miR-375, had an inverse association suggesting a direct effect on each other); TNFRSF11A was associated with 15 miRNAs, 11 of which had a seed-region match (nine of these seed-region matches suggest direct binding of the mRNA to the miRNA). TRAFs were originally shown to be a signal-transducing molecule for TNFR and IL1R (Tada et al. 2001). PLCG1 is generally activated by growth factor receptors such as vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFRs), insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF-1R) and FGFRs and has been linked to metastatic tumour progression (Lattanzio et al. 2013). TNFRSF11A or RANK expression in breast tumours has been found predominately in those tumours with a high grade and proliferation index (Sigl et al. 2016); it has also received attention as a possible therapeutic agent (Sigl et al. 2016; Gonzalez-Suarez and Sanz-Moreno 2016; Jimi et al. 2013).

There are several considerations when interpreting results from this study. Although our sample size is small, it is one of the largest available containing samples with paired carcinoma and normal mucosa data. While normal colonic mucosa may not be truly “normal”, it is the closest normal mucosa that can be used for a matched paired analysis. Furthermore, normal colonic mucosa was taken from the same colonic site as the tumour to prevent differences in expression from being the result of tumour location. We focused only on those genes that were statistically significant and also had a FC of > 1.5 or < 0.67. Using these criteria, we did not examine all statistically significant genes that were differentially expressed and miRNAs. A biologically important FC is not well defined, and using set values for further follow-up we could have missed genes associated with miRNAs. We exclusively used the KEGG pathway database to identify signalling pathway genes. Genes not identified in KEGG but associated with the NF-κB signalling pathway may importantly influence miRNA expression, but were not included in this analysis. When evaluating miRNA with mRNAs, we could have missed important associations since miRNAs may have their impact post-transcriptionally and we were only able to evaluate gene expression. However, much of the current information on miRNA target genes comes from gene expression data and associations observed may have important biological meaning, but must be acknowledged as being incomplete (Chou et al. 2016; Slattery et al. 2017). Thus, we encourage others to both replicate these findings and validate results in targeted laboratory experiments.

In conclusion, the NF-κB signalling pathway is a complex pathway that is important in the carcinogenic process of CRC. The alterations in gene expression observed in signalling pathway genes could influence immune response and promote inflammation through its downregulation of genes that have a positive role of immune response and upregulation of genes that are pro-inflammatory. Through examining of the entire pathway, we believe that we have obtained a more thorough understanding of those components of the pathway most important for CRC. It is important to have a comprehensive understanding of the complex associations that exist between mRNAs and miRNAs that co-regulate the pathway in order to accurately identify therapeutic targets, such as RANK.

References

Benjamini YH (1995) Y: Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Stat Soc 57:289–300

Chen C, Cheng P, Xie H, Zhou HD, Wu XP, Liao EY, Luo XH (2014) MiR-503 regulates osteoclastogenesis via targeting RANK. J Bone Miner Res 29(2):338–347

Chou CH, Chang NW, Shrestha S, Hsu SD, Lin YL, Lee WH, Yang CD, Hong HC, Wei TY, Tu SJ et al (2016) miRTarBase 2016: updates to the experimentally validated miRNA-target interactions database. Nucleic Acids Res 44(D1):D239–D247

Contreras J, Rao DS (2012) MicroRNAs in inflammation and immune responses. Leukemia 26(3):404–413

Gonzalez-Suarez E, Sanz-Moreno A (2016) RANK as a therapeutic target in cancer. FEBS J 283(11):2018–2033

Hill JM, Clement C, Zhao Y, Lukiw WJ (2015) Induction of the pro-inflammatory NF-kB-sensitive miRNA-146a by human neurotrophic viruses. Front Microbiol 6:43

Hoesel B, Schmid JA (2013) The complexity of NF-kappaB signaling in inflammation and cancer. Mol Cancer 12:86

Iliopoulos D, Hirsch HA, Struhl K (2009) An epigenetic switch involving NF-kappaB, Lin28, Let-7 MicroRNA, and IL6 links inflammation to cell transformation. Cell 139(4):693–706

Jimi E, Shin M, Furuta H, Tada Y, Kusukawa J (2013) The RANKL/RANK system as a therapeutic target for bone invasion by oral squamous cell carcinoma (Review). Int J Oncol 42(3):803–809

Karolchik D, Hinrichs AS, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Sugnet CW, Haussler D, Kent WJ (2004) The UCSC Table browser data retrieval tool. Nucleic Acids Res 32(Database issue):D493–D496

Lattanzio R, Piantelli M, Falasca M (2013) Role of phospholipase C in cell invasion and metastasis. Adv Biol Regul 53(3):309–318

Li T, Morgan MJ, Choksi S, Zhang Y, Kim YS, Liu ZG (2010) MicroRNAs modulate the noncanonical transcription factor NF-kappaB pathway by regulating expression of the kinase IKKalpha during macrophage differentiation. Nat Immunol 11(9):799–805

Li Y, Choi PS, Casey SC, Dill DL, Felsher DW (2014) MYC through miR-17–92 suppresses specific target genes to maintain survival, autonomous proliferation, and a neoplastic state. Cancer Cell 26(2):262–272

Li M, Long C, Yang G, Luo Y, Du H (2016a) MiR-26b inhibits melanoma cell proliferation and enhances apoptosis by suppressing TRAF5-mediated MAPK activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 471(3):361–367

Li Y, Lauriola M, Kim D, Francesconi M, D’Uva G, Shibata D, Malafa MP, Yeatman TJ, Coppola D, Solmi R et al (2016b) Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) regulates miR17–92 cluster through beta-catenin pathway in colorectal cancer. Oncogene 35(35):4558–4568

Ma X, Becker Buscaglia LE, Barker JR, Li Y (2011) MicroRNAs in NF-kappaB signaling. J Mol Cell Biol 3(3):159–166

Ma H, Pan JS, Jin LX, Wu J, Ren YD, Chen P, Xiao C, Han J (2016) MicroRNA-17 ~ 92 inhibits colorectal cancer progression by targeting angiogenesis. Cancer Lett 376(2):293–302

Merga YJ, O’Hara A, Burkitt MD, Duckworth CA, Probert CS, Campbell BJ, Pritchard DM (2016) Importance of the alternative NF-kappaB activation pathway in inflammation-associated gastrointestinal carcinogenesis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 310(11):G1081–G1090

Mima K, Nishihara R, Nowak JA, Kim SA, Song M, Inamura K, Sukawa Y, Masuda A, Yang J, Dou R et al (2016) MicroRNA MIR21 and T cells in colorectal cancer. Cancer Immunol Res 4(1):33–40

Mullany LE, Herrick JS, Wolff RK, Slattery ML (2016) MicroRNA seed region length impact on target messenger RNA expression and survival in colorectal cancer. PLoS One 11(4):e0154177

Pellatt AJ, Slattery ML, Mullany LE, Wolff RK, Pellatt DF: Dietary intake alters gene expression in colon tissue: possible underlying mechanism for the influence of diet on disease. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2016a

Pellatt DF, Stevens JR, Wolff RK, Mullany LE, Herrick JS, Samowitz W, Slattery ML (2016b) Expression profiles of miRNA subsets distinguish human colorectal carcinoma and normal colonic mucosa. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 7:e152

Pereira SG, Oakley F (2008) Nuclear factor-kappaB1: regulation and function. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 40(8):1425–1430

Sala G, Dituri F, Raimondi C, Previdi S, Maffucci T, Mazzoletti M, Rossi C, Iezzi M, Lattanzio R, Piantelli M et al (2008) Phospholipase C gamma1 is required for metastasis development and progression. Cancer Res 68(24):10187–10196

Sang W, Wang Y, Zhang C, Zhang D, Sun C, Niu M, Zhang Z, Wei X, Pan B, Chen W et al (2016) MiR-150 impairs inflammatory cytokine production by targeting ARRB-2 after blocking CD28/B7 costimulatory pathway. Immunol Lett 172:1–10

Schetter AJ, Nguyen GH, Bowman ED, Mathe EA, Yuen ST, Hawkes JE, Croce CM, Leung SY, Harris CC (2009) Association of inflammation-related and microRNA gene expression with cancer-specific mortality of colon adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 15(18):5878–5887

Sha M, Ye J, Zhang LX, Luan ZY, Chen YB, Huang JX (2014) Celastrol induces apoptosis of gastric cancer cells by miR-21 inhibiting PI3K/Akt-NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Pharmacology 93(1–2):39–46

Sigl V, Owusu-Boaitey K, Joshi PA, Kavirayani A, Wirnsberger G, Novatchkova M, Kozieradzki I, Schramek D, Edokobi N, Hersl J et al (2016) RANKL/RANK control Brca1 mutation-driven mammary tumors. Cell Res 26(7):761–774

Slattery ML, Fitzpatrick FA (2009) Convergence of hormones, inflammation, and energy-related factors: a novel pathway of cancer etiology. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa) 2(11):922–930

Slattery ML, Potter J, Caan B, Edwards S, Coates A, Ma KN, Berry TD (1997) Energy balance and colon cancer–beyond physical activity. Cancer research 57(1):75–80

Slattery ML, Caan BJ, Benson J, Murtaugh M (2003) Energy balance and rectal cancer: an evaluation of energy intake, energy expenditure, and body mass index. Nutr Cancer 46(2):166–171

Slattery ML, Pellatt DF, Mullany LE, Wolff RK, Herrick JS (2015a) Gene expression in colon cancer: a focus on tumor site and molecular phenotype. Genes Chromosom Cancer 54(9):527–541

Slattery ML, Herrick JS, Mullany LE, Valeri N, Stevens J, Caan BJ, Samowitz W, Wolff RK (2015b) An evaluation and replication of miRNAs with disease stage and colorectal cancer-specific mortality. Int J Cancer 137(2):428–438

Slattery ML, Herrick JS, Pellatt DF, Stevens JR, Mullany LE, Wolff E, Hoffman MD, Samowitz WS, Wolff RK (2016) MicroRNA profiles in colorectal carcinomas, adenomas and normal colonic mucosa: variations in miRNA expression and disease progression. Carcinogenesis 37(3):245–261

Slattery ML, Herrick JS, Mullany LE, Samowitz WS, Sevens JR, Sakoda L, Wolff RK: The co-regulatory networks of tumor suppressor genes, oncogenes, and miRNAs in colorectal cancer. Genes Chromosom Cancer 2017a

Slattery ML, Herrick JS, Stevens JR, Wolff RK, Mullany LE (2017b) An assessment of database-validated microRNA target genes in normal colonic mucosa: implications for pathway analysis. Cancer Inform 16:1176935117716405

Tada K, Okazaki T, Sakon S, Kobarai T, Kurosawa K, Yamaoka S, Hashimoto H, Mak TW, Yagita H, Okumura K et al (2001) Critical roles of TRAF2 and TRAF5 in tumor necrosis factor-induced NF-kappa B activation and protection from cell death. J Biol Chem 276(39):36530–36534

Tsitsiou E, Lindsay MA (2009) microRNAs and the immune response. Curr Opin Pharmacol 9(4):514–520

Waugh DJ, Wilson C (2008) The interleukin-8 pathway in cancer. Clin Cancer Res 14(21):6735–6741

Wei C, Li L, Kim IK, Sun P, Gupta S (2014) NF-kappaB mediated miR-21 regulation in cardiomyocytes apoptosis under oxidative stress. Free Radic Res 48(3):282–291

Zhang S, Shan C, Kong G, Du Y, Ye L, Zhang X (2012) MicroRNA-520e suppresses growth of hepatoma cells by targeting the NF-kappaB-inducing kinase (NIK). Oncogene 31(31):3607–3620

Acknowledgements

The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the National Cancer Institute. We acknowledge Sandra Edwards for data oversight and study management, and Michael Hoffman and Erica Wolff for miRNA analysis. We acknowledge Dr. Bette Caan and the staff at the Kaiser Permanente Northern California for sample and data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MS obtained funding, planned study, oversaw study data collection and analysis, and wrote the manuscript. JS provided input into the statistical analysis, LM conducted bioinformatics analysis and helped write manuscript. LS provided data from KPNC and gave input into the manuscript. RW oversaw laboratory analysis and read final version of the manuscript. WS reviewed and edited the manuscript and did pathology overview for the study. JH conducted statistical analysis and managed data. All authors approved final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was supported by NCI Grant CA163683.

Conflict of interest

Authors have no conflict of interest to report.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The Institutional Review Boards at the University of Utah and at KPNC approved the study.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from participants included in the study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Slattery, M.L., Mullany, L.E., Sakoda, L. et al. The NF-κB signalling pathway in colorectal cancer: associations between dysregulated gene and miRNA expression. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 144, 269–283 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-017-2548-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-017-2548-6