Abstract

Background

Remdesivir is an antiviral medicine approved for the treatment of mild‐to‐moderate coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). This led to widespread implementation, although the available evidence remains inconsistent. This update aims to fill current knowledge gaps by identifying, describing, evaluating, and synthesising all evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) on the effects of remdesivir on clinical outcomes in COVID‐19.

Objectives

To assess the effects of remdesivir and standard care compared to standard care plus/minus placebo on clinical outcomes in patients treated for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) infection.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane COVID‐19 Study Register (which comprises the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), PubMed, Embase, ClinicalTrials.gov, World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, and medRxiv) as well as Web of Science (Science Citation Index Expanded and Emerging Sources Citation Index) and WHO COVID‐19 Global literature on coronavirus disease to identify completed and ongoing studies, without language restrictions. We conducted the searches on 31 May 2022.

Selection criteria

We followed standard Cochrane methodology.

We included RCTs evaluating remdesivir and standard care for the treatment of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection compared to standard care plus/minus placebo irrespective of disease severity, gender, ethnicity, or setting.

We excluded studies that evaluated remdesivir for the treatment of other coronavirus diseases.

Data collection and analysis

We followed standard Cochrane methodology.

To assess risk of bias in included studies, we used the Cochrane RoB 2 tool for RCTs. We rated the certainty of evidence using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach for outcomes that were reported according to our prioritised categories: all‐cause mortality, in‐hospital mortality, clinical improvement (being alive and ready for discharge up to day 28) or worsening (new need for invasive mechanical ventilation or death up to day 28), quality of life, serious adverse events, and adverse events (any grade).

We differentiated between non‐hospitalised individuals with asymptomatic SARS‐CoV‐2 infection or mild COVID‐19 and hospitalised individuals with moderate to severe COVID‐19.

Main results

We included nine RCTs with 11,218 participants diagnosed with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and a mean age of 53.6 years, of whom 5982 participants were randomised to receive remdesivir. Most participants required low‐flow oxygen at baseline. Studies were mainly conducted in high‐ and upper‐middle‐income countries. We identified two studies that are awaiting classification and five ongoing studies.

Effects of remdesivir in hospitalised individuals with moderate to severe COVID‐19

With moderate‐certainty evidence, remdesivir probably makes little or no difference to all‐cause mortality at up to day 28 (risk ratio (RR) 0.93, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.81 to 1.06; risk difference (RD) 8 fewer per 1000, 95% CI 21 fewer to 6 more; 4 studies, 7142 participants), day 60 (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.05; RD 35 fewer per 1000, 95% CI 73 fewer to 12 more; 1 study, 1281 participants), or in‐hospital mortality at up to day 150 (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.03; RD 11 fewer per 1000, 95% CI 25 fewer to 5 more; 1 study, 8275 participants).

Remdesivir probably increases the chance of clinical improvement at up to day 28 slightly (RR 1.11, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.17; RD 68 more per 1000, 95% CI 37 more to 105 more; 4 studies, 2514 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence). It probably decreases the risk of clinical worsening within 28 days (hazard ratio (HR) 0.67, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.82; RD 135 fewer per 1000, 95% CI 198 fewer to 69 fewer; 2 studies, 1734 participants, moderate‐certainty evidence).

Remdesivir may make little or no difference to the rate of adverse events of any grade (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.18; RD 23 more per 1000, 95% CI 46 fewer to 104 more; 4 studies, 2498 participants; low‐certainty evidence), or serious adverse events (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.07; RD 44 fewer per 1000, 95% CI 96 fewer to 19 more; 4 studies, 2498 participants; low‐certainty evidence).

We considered risk of bias to be low, with some concerns for mortality and clinical course. We had some concerns for safety outcomes because participants who had died did not contribute information. Without adjustment, this leads to an uncertain amount of missing values and the potential for bias due to missing data.

Effects of remdesivir in non‐hospitalised individuals with mild COVID‐19

One of the nine RCTs was conducted in the outpatient setting and included symptomatic people with a risk of progression. No deaths occurred within the 28 days observation period.

We are uncertain about clinical improvement due to very low‐certainty evidence. Remdesivir probably decreases the risk of clinical worsening (hospitalisation) at up to day 28 (RR 0.28, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.75; RD 46 fewer per 1000, 95% CI 57 fewer to 16 fewer; 562 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence). We did not find any data for quality of life.

Remdesivir may decrease the rate of serious adverse events at up to 28 days (RR 0.27, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.70; RD 49 fewer per 1000, 95% CI 60 fewer to 20 fewer; 562 participants; low‐certainty evidence), but it probably makes little or no difference to the risk of adverse events of any grade (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.10; RD 42 fewer per 1000, 95% CI 111 fewer to 46 more; 562 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence).

We considered risk of bias to be low for mortality, clinical improvement, and safety outcomes. We identified a high risk of bias for clinical worsening.

Authors' conclusions

Based on the available evidence up to 31 May 2022, remdesivir probably has little or no effect on all‐cause mortality or in‐hospital mortality of individuals with moderate to severe COVID‐19. The hospitalisation rate was reduced with remdesivir in one study including participants with mild to moderate COVID‐19. It may be beneficial in the clinical course for both hospitalised and non‐hospitalised patients, but certainty remains limited. The applicability of the evidence to current practice may be limited by the recruitment of participants from mostly unvaccinated populations exposed to early variants of the SARS‐CoV‐2 virus at the time the studies were undertaken.

Future studies should provide additional data on the efficacy and safety of remdesivir for defined core outcomes in COVID‐19 research, especially for different population subgroups.

Plain language summary

Remdesivir to treat people with COVID‐19

Is remdesivir (an antiviral medicine) an effective treatment for COVID‐19?

Key messages

• For adults hospitalised with COVID‐19, remdesivir probably has little or no effect on deaths up to 150 days after treatment compared with placebo (sham treatment) or usual care.

• Remdesivir probably slightly raises the chance for hospitalised patients to improve and get discharged (leave the hospital or go home). It may also decrease the risk of becoming worse (invasive ventilation through a breathing tube or death).

• Usually patients who have mild symptoms and are not hospitalised are less likely to die. Remdesivir probably reduces the risk of getting worse and being hospitalised, but we cannot say if it affects recovery (e.g. relief in symptoms).

• Future studies should investigate the impact of remdesivir on the course of COVID‐19 in different subgroups (e.g. less or more severely ill people).

What is remdesivir?

Remdesivir is a medicine that fights viruses. It has been shown to prevent the virus that causes COVID‐19 (SARS‐CoV‐2) from reproducing. Medical regulators have approved remdesivir to treat people with COVID‐19. Common reported side effects are nausea, vomiting, and headaches, as well as changes in blood tests.

What did we want to find out?

We wanted to know if remdesivir is an effective treatment for people with COVID‐19 and if it causes unwanted effects compared to placebo or usual care. Its effect could depend on how advanced the illness is when treatment begins. We therefore distinguished between hospitalised patients with moderate to severe disease (e.g. having ventilation) and non‐hospitalised people who have tested positive for COVID‐19 but have no or mild symptoms.

We were interested in the following outcomes for hospitalised patients:

• deaths in the 28 days after treatment or after more than 28 days, if available;

• deaths that occurred during hospitalisation;

• whether patients got better after treatment and were ready to be discharged;

• whether patients’ condition worsened so that they needed mechanical ventilation through a breathing tube or died;

• any unwanted effects; and

• serious unwanted effects.

We were interested in the following outcomes for non‐hospitalised patients:

• deaths in the 28 days after treatment or after more than 28 days, if available;

• whether patients got better after treatment so that they were free of symptoms;

• whether patients’ condition worsened so that they needed to be hospitalised or that they died;

• quality of life;

• any unwanted effects; and

• serious unwanted effects.

What did we do?

We searched for studies that investigated remdesivir to treat adults with COVID‐19 compared to placebo or standard care. Patients could be of any gender or ethnicity.

We compared and summarised the results of the studies and rated our confidence in the evidence, based on factors such as study methods and sizes.

What did we find?

We found eight studies with 10,656 people hospitalised with moderate to severe COVID‐19 and one study with 562 people with mild COVID‐19. Of these, 5982 people were given remdesivir. No studies evaluated people without symptoms of COVID‐19. The average age of patients was 59 years.

Main results

The included studies compared remdesivir and usual care to usual care (plus/minus placebo) in people with COVID‐19.

Hospitalised people with moderate to severe COVID‐19

Remdesivir probably makes little or no difference to deaths after 28 days, after 60 days, or to deaths in hospital during 150 days. It probably raises the chance for patients to get better slightly, and it probably lowers the risk of getting worse. The rates of unwanted effects of any severity were similar between the compared groups.

Non‐hospitalised people with mild COVID‐19

In the study with outpatients no one died during the investigation (28 days). After treatment with remdesivir, people were less likely to get worse and be hospitalised. We do not know whether remdesivir leads to more or less chance for patients to improve. Patients may suffer fewer serious unwanted effects with remdesivir than with placebo or standard care. The rates of unwanted effects of any severity were similar between the compared groups.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

We are moderately confident in the evidence for deaths and course of disease in hospitalised people. Our confidence in the evidence of all other results in this group is limited because of differences between studies and a possible influence of their methods. For non‐hospitalised people with mild COVID‐19, we are moderately confident in the evidence for worsening of patients' condition and unwanted effects. Our confidence in the evidence of all other results is limited, especially for improvement of patients' condition, for methodological reasons (e.g. measurements were carried out inadequately or are not comparable, or both) and different results between studies. The studies were conducted at a time when vaccine programmes had not been started and the virus differed from subsequent strains. Most of the people in the studies also live in high‐ and middle‐income countries. This might limit the applicability of the findings to people who are vaccinated and in low‐income countries with less access to medical care.

How up‐to‐date is this evidence?

This is an update of the initial review and the evidence is current to 31 May 2022.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Remdesivir and standard care versus standard care (plus/minus placebo) for individuals with moderate to severe COVID‐19.

| Remdesivir and standard care versus standard care (plus/minus placebo) for individuals with moderate to severe COVID‐19 | ||||||

| Patient or population: hospitalised adults with moderate to severe COVID‐19 Settings: in‐hospital Intervention: remdesivir (10 days) Comparator: placebo or standard care alone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects | Relative effect 95% CI | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Placebo or standard care alone | Remdesivir | |||||

| All‐cause mortality at up to day 281 | 108 per 1000 | 100 per 1000 (21 fewer to 6 more) | RR 0.93 (0.81 to 1.06) | 7142 (4 RCTs) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊖

MODERATE a |

Remdesivir probably makes little or no difference to all‐cause mortality up to 28 days. |

| All‐cause mortality at up to day 60 | 235 per 1000 | 200 per 1000 (73 fewer to 12 more) | RR 0.85 (0.69 to 1.05) | 1281 (1 RCT) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊖ MODERATE b | Remdesivir probably makes little or no difference to all‐cause mortality up to 60 days. |

| In‐hospital mortality at up to day 150 | 156 per 1000 | 145 per 1000 (25 fewer to 5 more) | RR 0.93 (0.84 to 1.03) | 8275 (1 RCT) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊖ MODERATE c | Remdesivir probably makes little or no difference to in‐hospital mortality up to 150 days. |

| Clinical improvement: participants alive and ready to be discharged at up to day 282 | 617 per 1000 | 685 per 1000 (37 more to 105 more) | RR 1.11 (1.06 to 1.17) | 2514 (4 RCTs) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊖ MODERATE d | Remdesivir probably increases the chance of clinical improvement slightly. |

| Clinical worsening: time to new need for invasive mechanical ventilation or death within 28 days3 | 544 per 1000 | 409 per 1000 (198 fewer to 69 fewer) | HR 0.67 (0.54 to 0.82) | 1734 (2 RCTs) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊖ MODERATE d | Remdesivir probably decreases the risk of clinical worsening up to day 28. |

| Adverse events (any grade) at up to day 28 | 579 per 1000 | 602 per 1000 (46 fewer to 104 more) | RR 1.04 (0.92 to 1.18) | 2498 (4 RCTs) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊖ ⊖ LOW a,e | Remdesivir may make little or no difference to the risk of adverse events (any grade). |

| Serious adverse events at up to day 28 | 273 per 1000 | 229 per 1000 (96 fewer to 19 more) | RR 0.84 (0.65 to 1.07) | 2498 (4 RCTs) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊖ ⊖ LOW a,e | Remdesivir may make little or no difference to the risk of serious adverse events. |

| CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RD: risk difference; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1. Time to all‐cause mortality (time‐to‐event): HR 0.88, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.16; 2 studies, 6513 participants; I² = 57%.

2. Time to clinical improvement (time‐to‐event): alive and ready to discharge: HR 1.06, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.20; 2 studies, 1225 participants; I2 = 0%.

3. Clinical worsening: new need for invasive mechanical ventilation or death: RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.94; RD 76 fewer per 1000, 95% CI 121 fewer to 15 fewer; 1 study, 683 participants; I² = not applicable; low‐certainty evidence.

aDowngraded one level due to serious imprecision because of wide confidence intervals in the studies and/or the 95% confidence interval includes both benefits and harms. bDowngraded one level due to serious imprecision because optimal information size not reached. cDowngraded one level due to serious risk of bias because of selective reporting. dDowngraded one level due to serious risk of bias because of lack of blinding. eDowngraded one level due to serious risk of bias because of lack of blinding and one study was stopped earlier than scheduled.

Summary of findings 2. Remdesivir and standard care versus standard care (plus/minus placebo) for individuals with asymptomatic SARS‐CoV‐2 infection or mild COVID‐19.

| Remdesivir and standard care versus standard care (plus/minus placebo) for individuals with asymptomatic SARS‐CoV‐2 infection or mild COVID‐19 | ||||||

| Patient or population: non‐hospitalised adults with mild COVID‐19 Settings: outpatient Intervention: remdesivir Comparator: placebo or standard care alone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects | Relative effect 95% CI | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Placebo or standard care alone | Risk with remdesivir | |||||

| All‐cause mortality at up to day 28 | — | — | Not estimable | 562 (1 RCT) | — | There were no events observed, thus it was not possible to determine whether remdesivir makes a difference to 28‐day mortality. |

| Clinical improvement: participants with symptom alleviation at up to day 14 | 250 per 1000 | 333 per 1000 (61 fewer to 289 more) | HR 1.41 (0.73 to 2.71) | 126 (1 RCT) | ⊕ ⊖ ⊖ ⊖ Very lowb,c |

We are uncertain whether remdesivir increases or decreases the chance of symptom alleviation by day 14. |

| Clinical worsening: participants admitted to hospital or deceased at up to day 28 | 64 per 1000 | 18 per 1000 (57 fewer to 16 fewer) |

RR 0.28 (0.11 to 0.75) | 562 (1 RCT) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊖ Moderatec | Remdesivir probably decreases the rate of hospitalisation or death by day 28. |

| Quality of life | — | — | — | — | — | Not reported. |

| Serious adverse events at up to day 28 | 67 per 1000 | 18 per 1000 (60 fewer to 20 fewer) |

RR 0.27 (0.10 to 0.70) | 562 (1 RCT) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊖ ⊖ Low c,d | Remdesivir may decrease the rate of serious adverse events by day 28. |

| Adverse events (any grade) at up to day 28 | 463 per 1000 | 421 per 1000 (111 fewer to 46 more) |

RR 0.91 (0.76 to 1.10) | 562 (1 RCT) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊖ Moderatec | Remdesivir probably makes little or no difference to the risk of adverse events (any grade). |

| CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to serious imprecision because there was only one study. bDowngraded two levels due to serious risk of bias and serious indirectness because of differences in pre‐defined outcome and measurement. cDowngraded one level due to serious imprecision because of wide confidence interval and optimal information size not reached. dDowngraded one level due to serious indirectness (due to huge overlap with COVID‐19 symptoms, already considered in hospitalisation or death).

Background

This work is part of a series of Cochrane Reviews investigating treatments and therapies for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). Reviews of this series share information in the background section and methodology based on the first published reviews about monoclonal antibodies and convalescent plasma (Kreuzberger 2021; Piechotta 2021), as well as recently published or updated reviews on Janus‐kinase inhibitors or systemic corticosteroids (Griesel 2022; Kramer 2022). They are part of the German research project “CEOsys” (COVID‐19 Evidence‐Ecosystem; CEOsys 2021).

Description of the condition

COVID‐19 is a rapidly spreading infectious disease caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2). On 11 March 2020, the WHO declared the current COVID‐19 outbreak as a pandemic (WHO 2020a). COVID‐19 is unprecedented compared to previous coronavirus outbreaks, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS, Table 3), with 813 and 858 deaths, respectively (WHO 2003; WHO 2019). Despite intensive international efforts to contain its spread, SARS‐CoV‐2 has resulted in an ongoing increase of new weekly cases and deaths in several regions around the globe (WHO 2022a). In the meantime, the emergence of SARS‐CoV‐2 variants with the potential for altered transmission or disease characteristics, or to impact the effectiveness of vaccines, therapeutics, diagnostics, or public health and social measures, challenges strategies to control disease spread (WHO 2022b).

1. Glossary.

| Phrase/Word | Meaning/Description |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) | ARDS is characterised by a massive response of the respiratory system to a wide variety of external and internal noxious stimuli. There is a disturbance of oxygen uptake and an acute onset. ARDS is the common end route of a wide variety of diseases leading to a severe systemic inflammatory response. The condition should be distinguished from disturbances of respiration caused by cardiac diseases. |

| Adverse event | An adverse event in the context of clinical trials is an unwanted medical occurrence in patients receiving a pharmacological or non‐pharmacological treatment, or both. An adverse event may not necessarily be considered to be related to the treatment. |

| Antimicrobials | Drugs used to treat diseases caused by micro‐organisms (bacteria, fungi, viruses, parasites). |

| Antiviral (medicine) | An agent that is directed against viruses |

| Bias | (Unconscious) distortion and misinterpretation of research results, especially those obtained experimentally. The most important sources for bias are as follows.

|

| Controlled non‐randomised study | A study in which the effects of a pharmacological or non‐pharmacological measure, or both, are compared between different groups of participants. The term 'controlled' means that the measure under investigation (intervention, verum) is compared with another measure (placebo or another intervention). The group of participants receiving the intervention under study is known as the intervention group. The group of participants who do not receive the intervention is known as the control group. A controlled non‐randomised study is easier to conduct than a randomised controlled trial, but has much less power (see bias). |

| Convalescent plasma | Blood plasma from patients who have had a disease (e.g. COVID‐19). Transfer of convalescent plasma to naive patients (patients who do not have antibodies themselves) leads to an increase in the immune defence of the receiving patient because convalescent plasma contains antibodies. |

| Corticosteroids | Hormones that are mainly produced in the adrenal cortex. Corticosteroids influence many biological processes in the organism, and are in particular closely linked to the immune system. Important naturally occurring representatives are cortisone and cortisol. Examples of synthetically produced corticosteroids are dexamethasone and budesonide. |

| Dichotomous | Dichotomy describes a system that can have exactly two mutually exclusive states. Example: either one has a certain disease (state A), or one does not have this disease (state B). The co‐occurrence of state A and state B is impossible. |

| Ebola | Ebola is a viral disease that is often severe. The Ebola virus belongs to the Filoviridae (from Latin 'filum' = filamentous). There are at least six different species of the virus. Ebola virus was previously called haemorrhagic fever because it is accompanied by high fever and severe internal and external bleeding. |

| Heterogeneous | Heterogeneity can be translated as 'non‐uniformity'. It is the opposite of homogeneity. In the context of meta‐analyses, heterogeneity is a measure of the comparability of clinical trials. For example, studies that examine different populations (e.g. children versus adults) have limited comparability and can lead to misleading conclusions when the data from such studies are pooled in a meta‐analysis. |

| Hydroxychloroquine | A drug related to chloroquine, which is used mainly for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, lupus erythematosus, and the prevention of malaria. |

| Immunocompromised status | Immunocompromised are people who have a congenital or acquired disorder of the immune response. Examples of acquired disorders include infection with HIV. Long‐term treatment with certain drugs (e.g. corticosteroids) can also lead to disorders/weakening of the immune response. |

| Interventions | The term 'intervention' in the context of clinical trials refers to the measure whose effect (superiority, inferiority, non‐inferiority) on a specific condition is to be assessed in comparison to other measures. An intervention need not always consist of the administration of a specific drug (so‐called non‐pharmacological interventions). |

| Mechanical ventilation | Mechanical ventilation is the term used to describe a procedure in which oxygen is supplied to the patient with the aid of ventilators or other devices. This measure is very restrictive and not without risk, and is therefore used only if the patient can no longer take in enough oxygen through his or her natural breathing (spontaneous respiration). In this review, the following procedures are subsumed under the term 'mechanical ventilation'.

|

| Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) | MERS is a respiratory disease caused by a coronavirus (MERS‐CoV). Most cases of the disease are asymptomatic. Diarrhoea is a common accompanying symptom. In severe cases, pneumonia develops. |

| Monoclonal antibody (MAB) | Antibodies in general are produced by the organism (specifically the immune system) when it is exposed to an antigen (for example, pathogenic micro‐organisms and viruses). By reacting with specific parts of the antigen, the antibody can render it harmless. So‐called monoclonal antibodies are produced by infecting mice with an antigen, for example. The immune system (especially the B cells) of the infected mouse then produces antibodies that are specifically active against the antigen. These cells accumulate in the spleen of the infected mouse. These cells are then isolated from the animal's spleen in a complicated process and multiplied in vitro (i.e. in the test tube). The resulting monoclonal antibodies are all derived from genetically identical cells and are directed against a specific antigen. Monoclonal antibodies are administered in medicine when the patient does not produce any antibodies or produces too few of his or her own. In addition, these specific antibodies also enable the identification of antigens in the detection of various diseases. |

| Nasal prongs | Nasal prongs, or nasal cannula, is a device used to deliver low‐flow oxygen to the nose through a small plastic tube. |

| Observational study | Data collection in a specific population under a specific research question. The essential characteristic of an observational study is that no intervention/experiment is carried out. |

| Placebo | A placebo is a dummy drug that does not contain a pharmacologically active substance. |

| Randomised controlled trial | A randomised controlled trial is the best way to obtain conclusions regarding the efficacy and effectiveness of a pharmacological or non‐pharmacological intervention, or both. The term 'controlled' means that the measure under investigation (intervention, verum) is compared with another measure (placebo or another intervention). The term 'randomised' means that the participants in the study are randomly assigned to one of two or more prespecified treatment groups. The group of participants receiving the intervention under study is known as the intervention group. The group of participants who do not receive the intervention is known as the control group. |

| Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) | A disease caused by SARS‐CoV, which, similar to COVID‐19, results in fever and muscle pain in combination with other flu‐like signs. In severe cases, atypical pneumonia may occur. |

| Systematic review | Scientific process of critical judgement of the data available with regard to a specific question. A 'systematic' approach is taken. This includes:

A systematic review can include a meta‐analysis, but this is not required. The aim of a systematic review is to answer the defined research question, or, if this is not possible, to identify gaps in the scientific coverage of the research question. |

The risk for severe disease mainly depends on underlying medical conditions, in addition to the serological status of the infected person and the causative virus variant. In patients without effective immunisation, such as unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated individuals, or individuals who fail to develop an immunological response despite being fully vaccinated, the risk for severe disease is higher among individuals aged 65 years or older, smokers, and those with certain underlying medical conditions such as cancer, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart conditions, immunocompromised state, obesity, sickle cell disease, or type 2 diabetes mellitus (Huang 2020; Liang 2020; Williamson 2020a). COVID‐19 case fatality ratios vary widely between countries and reporting periods, from 0.0% to more than 18% (Johns Hopkins 2022). However, these numbers may be misleading as they tend to overestimate the infection fatality ratio due to varying testing frequency, a lack of reporting dates, and variations in case definitions, especially in the beginning of the pandemic when the main focus was on severe cases (WHO 2020b).

The median incubation time and time to symptom onset depends on the virus variant and is estimated to be three days (range zero to eight days) in the case of an infection with the Omicron SARS‐CoV‐2 variant, which is shorter compared with previous reports for the Delta SARS‐CoV‐2 variant and other previously circulating non‐Delta SARS‐CoV‐2 variants (five to six days) (Brandal 2021; Lauer 2020). Sore throat, cough, fever, headache, fatigue, and myalgia or arthralgia are the most commonly reported symptoms (Brandal 2021; Struyf 2021). Other symptoms include dyspnoea, chills, nausea or vomiting, diarrhoea, and nasal congestion (CDC 2022). The reported frequency of asymptomatic infections varies greatly, depending on the time of the investigation, the cohort investigated, and the virus variant, and ranges between approximately 14% and 50% (Buitrago‐Garcia 2022).

A smaller proportion of infected individuals are affected by severe (approximately 11% to 20%) or critical (approximately 1% to 5%) disease with hospitalisation and intensive care unit (ICU) admittance due to respiratory failure, septic shock, or multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (Funk 2021; Lewnard 2022; Nyberg 2022; Wolter 2022; Wu 2020). In a case series from 12 New York hospitals, 14% of patients hospitalised due to COVID‐19 were treated in ICU (Richardson 2020). In an observational study of 10,021 hospitalised adult patients in Germany with a confirmed COVID‐19 diagnosis, 17% received mechanical ventilation (non‐invasive and invasive). Mortality in patients not receiving mechanical ventilation was 16%, and up to 53% in ventilated patients. Mortality in patients receiving mechanical ventilation (non‐invasive and invasive) and dialysis was 73% (Karagiannidis 2020). In one systematic review and meta‐analysis of international studies, the proportion of patients who died was estimated at 34% amongst those treated in ICU, and 83% amongst those receiving invasive mechanical ventilation (Potere 2020). However, the hospitalisation and ICU treatment rates seem to depend on the virus variant.

Analyses from the United Kingdom show a significant reduction in the relative risk of hospitalisation for adult Omicron cases compared to Delta (Nyberg 2022 ). There may also have been a different threshold for admission to hospital or ICU during the course of the pandemic. Depending on the local pressure on ICU resources, some normal wards will have learned to provide continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy equivalent to ICU support in other healthcare systems. It is unclear whether triage criteria in some healthcare systems may have influenced admission to hospital or ICU (or both).

As the evidence for the treatment options for COVID‐19 that were investigated in the course of the pandemic increased, national and international guidelines emerged to support daily clinical decisions (NICE guideline 2021; NIH guideline 2022; WHO living guideline 2022). However, so far there are only a few substances with clearly proven benefits and clear recommendations as well as approval by national and international authorities for the treatment of COVID‐19 (EMA 2022; FDA 2022a; WHO living guideline 2022). In light of the extent of the COVID‐19 pandemic and the scarcity of effective treatments, there is an urgent need for effective therapies to save lives and to reduce the high burden on healthcare systems (either with a high workload caused by COVID‐19 or staff shortages due to infected health care providers), especially in the face of evolving variants of the virus with the potential for increased transmissibility and the limited global availability of vaccines.

Description of the intervention

Remdesivir (GS‐5734) is an antiviral agent derived from a small‐molecule library and designed to target the replication of pathogenic ribonucleic acid (RNA) viruses (Siegel 2017). It showed a broad‐spectrum in vitro efficacy against various emerging viruses, such as Filoviridae (e.g. Ebolavirus and Marburgvirus), Pneumoviridae (respiratory syncytial virus), and Coronaviridae (MERS‐CoV, SARS‐CoV)) (Choy 2020; Sheahan 2017). Initially developed for the treatment of Ebola virus disease, studies on animals showed effective reduction in virus replication and clinical improvement for MERS as well as SARS infection (Sheahan 2020; Williamson 2020a; de Wit 2020).

During the course of the COVID‐19 pandemic, the antiviral agent was initially administered to hospitalised patients with COVID‐19 in a compassionate‐use attempt. The Adaptive COVID‐19 Treatment Trial (ACTT‐1) was one of the first multicentre RCTs to report a shortened time to recovery in hospitalised COVID‐19 patients compared to standard care (Beigel 2020). Shortly after its publication, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released an Emergency Use Authorisation on 1 May 2020 (EUA 2021). Based on the recommendation of the European Medicines Agency, the European Union Commission followed in July 2020 with the authorisation of remdesivir as the first treatment option in patients at least 12 years of age with COVID‐19 pneumonia and the need for supplementary oxygen (EUA 2020). Later that year, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use narrowed the indication to patients with low‐ or high‐flow oxygen or other non‐invasive ventilation (EMA 2020). Recently, the FDA expanded approval to paediatric patients of at least 28 days of age with a minimal weight of three kilograms who are hospitalised, or not hospitalised with mild‐to‐moderate COVID‐19 and a high risk for progression to severe COVID‐19, including hospitalisation or death (FDA 2022b). However, supporting data have not been published to date and the paediatric trial by the manufacturer, Gilead Science, is still ongoing (NCT04431453). The recommended regimen has been changed to an intravenous route of three days instead of 10. Proposed dosing is 200 mg intravenously (loading dose), followed by 100 mg for adults and 5 mg/kg followed by 2.5 mg/kg for children of 3.5 kg to less than 40 kg (EUA 2022). To date, the available data revealed good tolerability and safety of intravenous administration of remdesivir in healthy individuals. Reported common side effects include nausea, headache, rash, as well as transient increase in transaminases, prothrombin time, and blood glucose in laboratory findings (NIH guideline 2022).

Meanwhile, further RCTs have added to the evidence of the efficacy and safety of remdesivir application in adolescent and adult COVID‐19 patients. Amongst them were the interim results of the WHO Solidarity trial, which could not find a benefit for time to clinical improvement, need for mechanical ventilation, or mortality (WHO Solidarity Trial Consortium 2022). Based on a meta‐analysis of four RCTs, including the preprint data from the aforementioned trial, the WHO COVID‐19 treatment guideline recommended against the use of remdesivir in hospitalised patients in November 2020 (WHO 2022c). As the first RCT evaluating remdesivir usage in an outpatient setting, the PINETREE trial showed a reduction in hospitalisation in ambulatory patients with symptomatic COVID‐19 (Gottlieb 2021). This led the guideline development group to an update in April 2022, suggesting treatment with remdesivir for patients with non‐severe illness at highest risk of hospitalisation (WHO 2022c).

How the intervention might work

Remdesivir (GS‐5734) is a mono phosphoramidate nucleoside prodrug, which inhibits the synthesis of viral RNA. By competing with its natural analogue adenosine triphosphate, it blocks the RNA‐polymerase and leads to delayed chain termination, hence inhibiting the virus replication (Siegel 2017). The addition of the monophosphate prodrug improves the intracellular uptake, where phosphorylation turns it into its active metabolite (Lo 2017; McGuigan 2006).

In the early stage of a SARS‐CoV‐2‐associated pneumonia, the reduction of the viral load is postulated to prevent a systemic inflammatory reaction and, in particular, alveolar damage. The clinical presentation of COVID‐19 in the late pulmonary phase as well as in the hyper inflammatory phase is dominated by immunological processes, so that antiviral therapy strategies are no longer likely to be effective (Gautret 2020).

In summary, the broad‐spectrum nucleoside analogue remdesivir could be beneficial in the early stages of SARS‐CoV‐2‐infection by inhibiting virus replication. This hypothesis is supported by promising in vitro and animal experiments (Choy 2020; Wang 2020; Williamson 2020b), and could be the rationale for the current recommendation of early application to prevent disease progression. However, a new laboratory study shows that mutations in the viral polymerase can lead to partial resistance to remdesivir (Stevens 2022). This highlights the importance of targeted use in patients with the highest expected benefit as well as re‐evaluation of its effect in virus variants.

Why it is important to do this review

There is a clear and urgent need for more evidence‐based information to guide clinical decision‐making for COVID‐19 patients. Current standard care consists of supportive care with oxygen supply in moderately severe cases, and non‐invasive ventilation or invasive mechanical ventilation and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in severe cases. Systematic corticosteroids were the first formulation to show a reduction in mortality as well as risk for disease progression and became recommended standard care, however solely for severe or critical COVID‐19 (Wagner 2021; WHO 2022c). To date, there have been applications for emergency use authorisation for several drugs. Few of them have been approved for the treatment of COVID‐19 in the European Union (such as monoclonal antibodies) and international guidelines on their clinical implementation are constantly updated (EMA 2022). Remdesivir remains the only fully FDA‐approved drug for usage in COVID‐19, in particular for early‐stage disease, with widespread implementation.

The first version of this review represents the difficulty in comparing available data due to inconsistent endpoint definitions (Ansems 2021). We included five RCTs with 7452 participants and concluded with moderate certainty that remdesivir probably has little or no effect on all‐cause mortality at up to 28 days in hospitalised adults with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. However, when it comes to analysis of patient subgroups by disease severity at baseline, as well as reduction of symptom severity and disease progression, the evidence left us uncertain about its efficacy. The publication of further trials, assessing this lack of evidence, led to a change from recommendation against its application to conditional recommendation for certain patients. Additionally, the reduced susceptibility to monoclonal antibodies of the Omicron variant of concern calls for a re‐evaluation, considering that remdesivir is believed to remain active against variants in cell cultures (Vangeel 2022).

This first update of this systematic review aims to fill current gaps by identifying, describing, evaluating, and synthesising all evidence for remdesivir on clinical outcomes in COVID‐19. There is a need for a thorough understanding and an extensive review of the current body of evidence regarding the use of remdesivir for the treatment of COVID‐19. The primary goal of this update is to provide practising clinicians, healthcare providers, and interested laypersons with reliable and evidence‐based information that will lead to improvement in the treatment of COVID‐19.

Objectives

To assess the effects of remdesivir and standard care compared to standard care plus/minus placebo on clinical outcomes in patients treated for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

The main description of methods is based on a template from the Cochrane Haematology working group in line with the series of Cochrane Reviews investigating treatments and therapies for COVID‐19. We made specific adaptations related to the research question where necessary. The protocol for this review was registered with PROSPERO on 26 February 2021 (CRD42021238065).

To assess the effects of remdesivir for treatment in COVID‐19, we included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), as this study design, if performed appropriately, provides the best evidence for experimental therapies in highly controlled therapeutic settings. We used the methods recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2022a). We had planned to also accept non‐standard RCT designs, such as cluster‐randomised trials (methods as recommended in Chapter 23 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions) and cross‐over trials (Higgins 2022b). We would only have considered results from the first period for cross‐over trials, because COVID‐19 is not a chronic condition, and its exact course and long‐term effects have yet to be defined.

We excluded controlled non‐randomised studies of the intervention and observational studies. We also excluded animal studies, pharmacokinetic studies, and in vitro studies.

We included the following formats, if sufficient information was available on study design, characteristics of participants, interventions, and outcomes.

Full‐text publications

Preprint articles

Abstract publications

Results published in trials registries

Personal communication with investigators

We included preprints and conference abstracts to have a complete overview of the ongoing research activity, especially for tracking newly emerging studies about remdesivir in COVID‐19. We did not apply any limitation with respect to length of follow‐up.

Types of participants

We included adults with a confirmed diagnosis of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection (as described in the study) and did not exclude any studies based on gender, ethnicity, disease severity, or setting.

We excluded studies that evaluated remdesivir for the treatment of other coronavirus diseases such as SARS or MERS, or other viral diseases, such as Ebola. We planned that if studies enrolled populations with or who were exposed to mixed viral diseases, we would only include these if the trial authors provided subgroup data for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection.

Types of interventions

We included the following interventions, independent of dose, frequency, and duration:

Remdesivir and standard care for the treatment of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection.

We included the following control groups:

Standard care (plus/minus placebo).

Types of outcome measures

We evaluated core outcomes based on the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) initiative for people with COVID‐19 (COMET 2020), and additional outcomes that have been prioritised by consumer representatives and the German guideline panel for therapy of people with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection.

We defined outcome sets with primary and secondary outcomes for two populations:

hospitalised individuals with moderate to severe COVID‐19 (defined as participants with SARS‐CoV‐2 detection and need for inpatient medical care plus/minus need for respiratory support with low‐flow oxygen, high‐flow oxygen, non‐invasive mechanical ventilation, invasive mechanical ventilation (plus/minus ECMO) due to COVID‐19); and

non‐hospitalised individuals with asymptomatic SARS‐CoV‐2 infection or mild COVID‐19 (defined as participants with SARS‐CoV‐2 detection plus/minus symptoms of COVID‐19 without need for inpatient medical care or respiratory support).

Primary outcomes were used to inform the summary of findings tables.

Hospitalised individuals with moderate to severe COVID‐19

Primary outcomes

All‐cause mortality at day 28.

All‐cause mortality at day 60 and up to longest follow‐up.

In‐hospital mortality at up to longest follow‐up.

Clinical improvement: proportion of participants alive and ready to be discharged at up to day 28, up to longest follow‐up, and time‐to‐event. Participants should be discharged without clinical deterioration or death.

Clinical worsening: proportion of participants with new need for invasive mechanical ventilation or deceased within 28 days, up to longest follow‐up, and time‐to‐event.

Adverse events (any grade) during the study period, defined as number of participants with any event.

Serious adverse events during the study period, defined as number of participants with any event.

Secondary outcomes

All‐cause mortality, time‐to‐event.

Quality of life, including fatigue and neurological status, assessed with standardised scales (e.g. WHO Quality of Life 100‐question patient‐reported questionnaire (WHOQOL‐100)) at up to seven days, up to 28 days, and longest follow‐up available.

Adverse events grades 3 and 4.

Ventilator‐free days (defined as days alive and free from mechanical ventilation).

Non‐hospitalised individuals with asymptomatic SARS‐CoV‐2 infection or mild COVID‐19

All‐cause mortality at day 28, up to longest follow‐up, and time‐to‐event.

Clinical improvement: proportion of participants with symptom resolution (all symptoms resolved) at up to day 14, day 28, up to longest follow‐up, and time‐to‐event.

Clinical worsening: proportion of participants admitted to the hospital or deceased within 14 days, 28 days, up to longest follow‐up, and time‐to‐event.

Quality of life, including fatigue and neurological status, assessed with standardised scales (e.g. WHOQOL‐100) at up to seven days, up to 28 days, and longest follow‐up available.

Serious adverse events during the study period, defined as number of participants with any event.

Adverse events (any grade) during the study period, defined as number of participants with any event.

Timing of outcome measurement

In the case of time‐to‐event analysis (e.g. for time to discharge from hospital and time to mortality), we included the outcome measure based on the longest follow‐up time. We also collected information on outcomes from all other time points reported in the publications.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Our Information Specialist (MIM) conducted systematic searches in the following sources from the inception of each database to 31 May 2022 (date of last search for all databases), placing no restrictions on the language of publication.

-

Cochrane COVID‐19 Study Register (CCSR) (covid-19.cochrane.org/) comprising:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), monthly updates;

PubMed, weekly updates;

Embase.com, weekly updates;

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov), daily updates;

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP) (trialsearch.who.int), weekly updates;

medRxiv (www.medrxiv.org), weekly updates.

-

Web of Science Clarivate:

Science Citation Index Expanded (1945 to 31 May 2022);

Emerging Sources Citation Index (2015 to 31 May 2022).

WHO COVID‐19 Global literature on coronavirus disease (search.bvsalud.org/global-literature-on-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov/).

We did not conduct separate searches of the databases as required by the MECIR standards (Higgins 2022a), since these databases are regularly searched in the production of the CCSR.

For detailed search strategies, see Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We identified other potentially eligible studies or ancillary publications by searching the reference lists of included studies, systematic reviews, and meta‐analyses. In addition, we contacted investigators of the included studies to obtain additional information on the retrieved studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Four review authors (FG, KA, KD, VT) independently screened the results of the search strategies for eligibility by reading the titles and abstracts using Covidence software (Covidence 2021). We coded the abstracts as either 'include' or 'exclude'. In the case of disagreement, or if it was unclear whether the abstract should be retrieved, we obtained the full‐text publication for further discussion. Several review authors (FG, KA, KD, VT) assessed the full‐text articles of the selected studies. If two review authors were unable to reach a consensus, they consulted a third review author to reach a final decision.

As recommended in the PRISMA statement (Moher 2009), we documented the study selection process in a flow chart showing the total numbers of retrieved references and the numbers of included and excluded studies. We listed all studies excluded after full‐text assessment and the reasons for their exclusion in the Excluded studies section.

Data extraction and management

We conducted data extraction according to the guidelines proposed by Cochrane (Li 2020). Several review authors (FG, KA, KD, VT, AM, NS) extracted data independently and in duplicate, using a customised data extraction form developed in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft 2018). Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or by consulting a third review author if necessary.

Two out of several review authors (FG, KA, KD, AM, VT, MG, NS) independently assessed the included studies for methodological quality and risk of bias. If the review authors were unable to reach a consensus, a third review author was consulted.

We extracted the following information, where reported.

General information: author, title, source, publication date, country, language, duplicate publications.

Study characteristics: trial design, setting, and dates, source of participants, inclusion/exclusion criteria, comparability of groups, treatment cross‐overs, compliance with assigned treatment, length of follow‐up.

Participant characteristics: age, gender, ethnicity, number of participants recruited/allocated/evaluated, additional diagnoses, severity of disease, previous treatments, concurrent treatments, comorbidities (e.g. diabetes, respiratory disease, hypertension, immunosuppression, obesity, heart failure).

Interventions: dosage, frequency, timing, duration and route of administration, setting, duration of follow‐up.

Control interventions (placebo or standard care alone): dosage, frequency, timing, duration and route of administration, setting, duration of follow‐up.

Outcomes: as specified in Types of outcome measures section.

Risk of bias assessment: randomisation process, deviations from the intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, selection of the reported result.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We used the RoB 2 tool (beta version 7) to analyse the risk of bias of the included studies (Sterne 2019). Of interest in this review was the effect of the assignment to the intervention (the intention‐to‐treat effect), thus we performed all assessments with RoB 2 on this effect. The outcomes that we assessed are those specified for inclusion as described in the Methods section.

Two out of several review authors (FG, KA, KD, AM, VT, MG, NS) independently assessed the risk of bias for each outcome using the RoB 2 Excel tool to manage and record assessments. In case of discrepancies amongst judgements and inability to reach consensus, a third review author was consulted reach a final decision. We assessed the following types of bias as outlined in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2022c).

Bias arising from the randomisation process

Bias due to deviations from the intended interventions

Bias due to missing outcome data

Bias in measurement of the outcome

Bias in selection of the reported result

For cluster‐RCTs, we had planned to add a domain to assess bias arising from the timing of identification and recruitment of participants in relation to timing of randomisation, as recommended in the archived RoB 2 guidance for cluster‐randomised trials and in Chapter 23 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Eldridge 2016; Higgins 2022b).

To address these types of bias, we used the signalling questions recommended in RoB 2 and made a judgement according to the following options.

'Yes': if there is firm evidence that the question is fulfilled in the study (i.e. the study is at low or high risk of bias given the direction of the question).

'Probably yes': a judgement has been made that the question is fulfilled in the study (i.e. the study is at low or high risk of bias given the direction of the question).

'No': if there is firm evidence that the question is unfulfilled in the study (i.e. the study is at low or high risk of bias given the direction of the question).

'Probably no': a judgement has been made that the question is unfulfilled in the study (i.e. the study is at low or high risk of bias given the direction of the question).

'No information': if the study report does not provide sufficient information to permit a judgement.

We used the algorithms proposed by RoB 2 to assign each domain one of the following levels of bias.

Low risk of bias

Some concerns

High risk of bias

We subsequently derived an overall risk of bias rating for each prespecified outcome in each study in accordance with the following suggestions.

'Low risk of bias': we judge the trial to be at low risk of bias for all domains for the result.

'Some concerns': we judge the trial to raise some concerns in at least one domain for the result, but not to be at high risk of bias for any domain.

'High risk of bias': we judge the trial to be at high risk of bias in at least one domain for the result, or we judge the trial to have some concerns for multiple domains in a way that substantially lowers our confidence in the results.

We used the RoB 2 Excel tool to implement RoB 2 (beta version 7, available from riskofbias.info), and stored and presented our detailed RoB 2 assessments in the analyses section and as supplementary online material.

For domain three of the tool ('bias due to missing outcome data'), we considered death as a competing risk factor, especially for dichotomous clinical progression outcomes. We judged improvement to be at high risk of bias due to missing data because it is likely that death during follow‐up impeded liberation from respiratory support, and hence missing data on improvement depends on its true value.

Measures of treatment effect

For continuous outcomes, we recorded the mean, standard deviation, and total number of participants in both the treatment and control groups. Where continuous outcomes used the same scale, we performed analyses using the mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For continuous outcomes measured with different scales, we performed analyses using the standardised mean difference (SMD). In our interpretation of SMDs, we re‐expressed SMDs in the original units of a particular scale with the most clinical relevance and impact (e.g. clinical symptoms with the WHO Clinical Progression Scale) (WHO 2020c).

For dichotomous outcomes, we recorded the number of events and the total number of participants in both the treatment and control groups. We reported the pooled risk ratio (RR) with its associated 95% CI, and risk difference (RD) with its associated 95% CI (Deeks 2020).

If sufficient information was available, we extracted and reported hazard ratios (HRs) for time‐to‐event outcomes (e.g. time to mortality). If HRs were not available, we made every effort to estimate the HR as accurately as possible from available data using the methods proposed by Parmar and Tierney (Parmar 1998; Tierney 2007). If a sufficient number of studies provided HRs, we used HRs rather than RRs or MDs in a meta‐analysis, as they provide more information.

Unit of analysis issues

The aim of this review was to summarise trials that analyse data at the level of the individual. We would also have accepted cluster‐randomised trials for inclusion had any been identified. We collated multiple reports of a given study so that each study, rather than each report, was the unit of analysis.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

As recommended in Chapter 6 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2022d), for studies with multiple treatment groups of the same intervention (i.e. dose, route of administration), we planned to evaluate if study arms were sufficiently homogeneous to be combined. We planned that if study arms could not be pooled, we would compare each arm with the common comparator separately. For pair‐wise meta‐analysis, we planned to split the ‘shared’ group into two or more groups with a smaller sample size, and include two or more (reasonably independent) comparisons. For this purpose, both the number of events and the total number of participants would have been divided for dichotomous outcomes, and the total number of participants would have been divided with unchanged means and standard deviations for continuous outcomes.

One study included in the review had multiple treatment arms of the same intervention (5‐day course of remdesivir versus 10‐day course of remdesivir) (Spinner 2020). Given the small number of participants in this study, we did not perform meta‐analysis, but have reported the results for each treatment arm narratively in our subgroup analysis (see Effects of interventions, Duration of remdesivir application).

Dealing with missing data

In Chapter 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, a number of potential sources for missing data are suggested, which we took into account: at study level, at outcome level, and at summary data level (Deeks 2020). At all levels, it is important to differentiate between data 'missing at random', which may often be unbiased, and 'not missing at random', which may bias the study and in turn the review results.

In the case of missing data, we requested this information from the principal investigators; details are provided in the Included studies section. Beigel 2020 and Spinner 2020 provided additional data on all‐cause mortality at up to day 28 for subgroups of respiratory support, and Spinner 2020 provided data on clinical course.

If, after this, data were still missing, we consulted with content experts to judge whether data were missing at random (e.g. if missing outcomes were balanced across study arms, reasons for loss to follow‐up were common and reasonable). If we judged data to be missing at random, we performed a complete case analysis. When we judged data to be not missing at random, and we identified no supporting evidence that the results were not biased by missing outcome data, we did not make any assumptions about the missing outcome data. We had planned to conduct sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of missing data on the overall effect (excluding studies with more than 10% missing outcome data), however none of the included studies had more than 10% of missing outcome data. In future updates, we will discuss the potential impact of missing data on results.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity of treatment effects between trials using a Chi² test with a significance level of P < 0.1. We used the I² statistic, Higgins 2003, and visual examination of the forest plot, to assess possible heterogeneity (I² > 30% to signify moderate heterogeneity, I² > 75% to signify considerable heterogeneity) (Deeks 2020). We planned that if the I2 was above 80%, we would explore possible causes of heterogeneity through sensitivity analyses. If we could not find a reason for heterogeneity, we would not perform a meta‐analysis, but instead would comment on the results from all studies and present these in tables.

Assessment of reporting biases

As mentioned above, we searched the trials registries to identify completed trials that have not been published elsewhere, to minimise publication bias or determine publication bias. We intended to explore potential publication bias by generating a funnel plot and statistically testing this by conducting a linear regression test for meta‐analyses involving at least 10 trials (Sterne 2019). We would consider P < 0.1 as significant for this test.

Data synthesis

If the clinical and methodological characteristics of individual studies were sufficiently homogeneous, we pooled the data in meta‐analysis. We performed analyses according to the recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2020). We planned to treat placebo and no treatment as the same intervention, as well as standard care at different institutions and time points.

We used the Review Manager Web (RevMan Web) software for analyses (RevMan Web 2021). One review author entered the data into the software, and a second review author checked the data for accuracy. We used the random‐effects model for all analyses, as we anticipated that true effects would be related but not the same for included studies. We planned that if meta‐analysis was not possible, we would comment on the results narratively with the results from all studies, and present these in tables. If meta‐analysis was possible, we would assess the effects of potential biases in sensitivity analyses (see Sensitivity analysis). For binary outcomes, we based the estimation of the between‐study variance using the Mantel‐Haenszel method. We used the inverse‐variance method for continuous outcomes, outcomes that included data from cluster‐RCTs, or outcomes where HRs were available.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In the first version of this review we conducted subgroup analyses for all‐cause mortality at up to day 28 exclusively. Additional analyses were performed where longer follow‐up data on mortality were available.

In the case of sufficient data, we performed subgroup analyses of the following characteristics for remdesivir and standard care versus standard care plus/minus placebo.

Age of participants (divided into applicable age groups, e.g. 18 to 65 years, 65 to 79 years, 80 years and older).

Pre‐existing conditions (e.g. diabetes, respiratory disease, hypertension, immunosuppression, obesity, cardiac injury).

Timing of first dose administration with illness onset.

-

Severity of condition, based on respiratory support at baseline:

No oxygen versus low‐flow oxygen versus low‐flow or high‐flow oxygen versus mechanical ventilation (including high‐flow oxygen, non‐invasive ventilation, invasive mechanical ventilation, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation).

-

Duration of remdesivir application:

5‐day course of remdesivir versus 10‐day course of remdesivir.

We used the tests for interaction to test for differences between subgroup results.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analysis of the following study characteristics for our prioritised outcomes, as described in the Types of outcome measures section.

Risk of bias assessment components (studies with a low risk of bias or some concerns versus studies with a high risk of bias).

Comparison of preprints versus peer‐reviewed articles.

Comparison of premature termination of studies with completed studies.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We created Table 1 and Table 2 and evaluated the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach for interventions evaluated in RCTs.

Summary of findings

We used MAGICapp software to create summary of findings tables (MAGICapp). For time‐to‐event outcomes, we calculated absolute effects at specific time points, as recommended in the GRADE guidance 27 (Skoetz 2020).

Chapter 14 of the updated Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions specifies that the “most critical and/or important health outcomes, both desirable and undesirable, limited to seven or fewer outcomes” should be included in the summary of findings table(s) (Schünemann 2021). We included our primary outcomes prioritised according to the Core Outcome Set for intervention studies, COMET 2020, and patient relevance; these are listed below.

Hospitalised individuals with moderate to severe COVID‐19

All‐cause mortality: all‐cause mortality at up to day 28 and longest follow‐up available.

In‐hospital mortality: in‐hospital mortality at up to longest follow‐up available.

Clinical improvement: proportion of participants alive and ready to be discharged at up to day 28, up to longest follow‐up, and time‐to‐event. Participants should be discharged without clinical deterioration or death.

Clinical worsening: proportion of participants with new need for invasive mechanical ventilation or deceased within 28 days, up to longest follow‐up, and time‐to‐event.

Adverse events (any grade).

Serious adverse events.

Non‐hospitalised individuals with asymptomatic SARS‐CoV‐2 infection or mild COVID‐19

All‐cause mortality: all‐cause mortality at up to day 28 and longest follow‐up available.

Clinical improvement: proportion of participants with symptom resolution (all symptoms resolved) at up to day 14, day 28, up to longest follow‐up, and time‐to‐event.

Clinical worsening: proportion of participants admitted to the hospital or deceased within 14 days, 28 days, up to longest follow‐up, and time‐to‐event.

Quality of life: quality of life, including fatigue and neurological status, assessed with standardised scales (e.g. WHOQOL‐100) at up to seven days, up to 28 days, and longest follow‐up available.

Adverse events (any grade).

Serious adverse events.

Assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We used the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of the evidence for the outcomes listed above.

The GRADE approach uses five domains (risk of bias, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to assess the certainty of the body of evidence for each prioritised outcome.

We downgraded the certainty of the evidence for:

serious (−1) or very serious (−2) risk of bias;

serious (−1) or very serious (−2) inconsistency;

serious (−1) or very serious (−2) uncertainty about directness;

serious (−1) or very serious (−2) imprecise or sparse data;

serious (−1) or very serious (−2) probability of reporting bias.

The GRADE system uses the following criteria for assigning grades of evidence.

High: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

We followed the current GRADE guidance for these assessments in its entirety as recommended in Chapter 14 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2021).

We used the overall risk of bias judgement, derived from the RoB 2 Excel tool, to inform our decision on downgrading the certainty of the evidence for risk of bias. We phrased the findings and certainty of the evidence as suggested in the informative statement guidance (Santesso 2020).

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies, and Characteristics of ongoing studies tables.

Results of the search

In the primary review (Ansems 2021) we included 42 records (five studies: Beigel 2020; Mahajan 2021; Spinner 2020; Wang 2020; WHO Solidarity Trial Consortium 2022) in our narrative analysis and 41 records (four studies: Beigel 2020; Spinner 2020; Wang 2020; WHO Solidarity Trial Consortium 2022) in our meta‐analyses. Two studies were listed as ongoing (NCT04252664; NCT04596839).

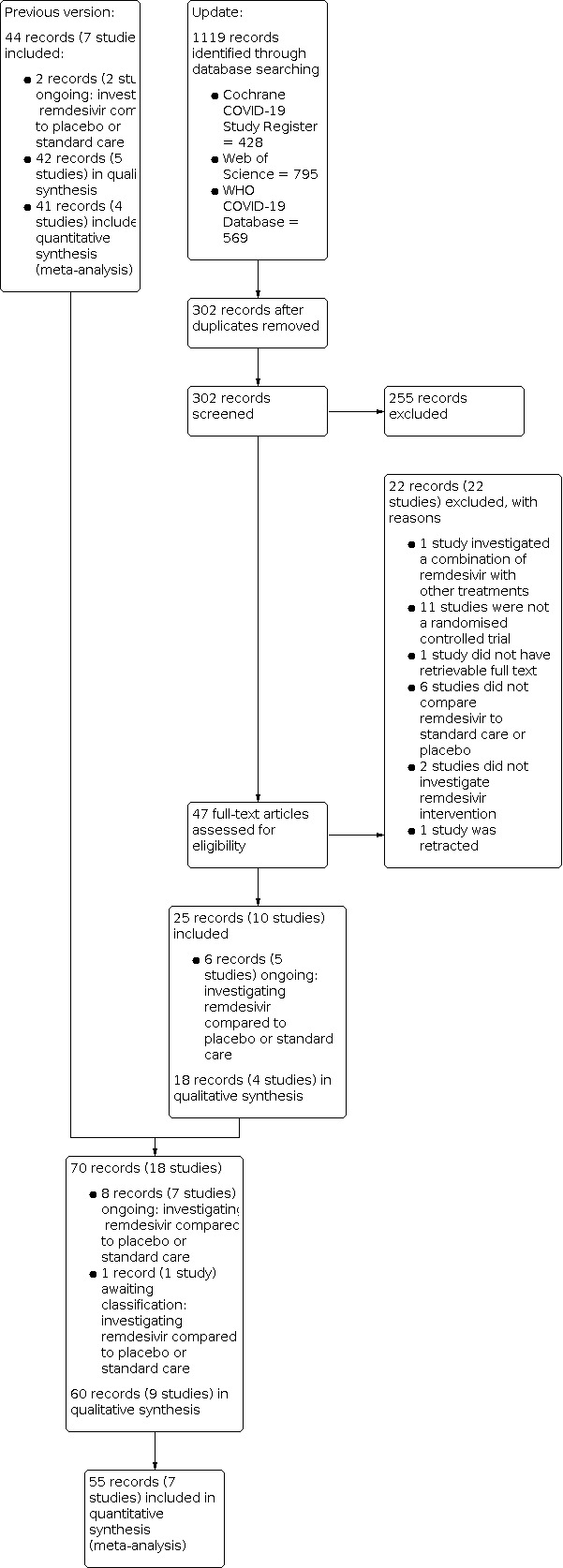

We performed update searches on 31 May 2022 and identified 1119 records. After removing duplicates, we screened 302 records based on title and abstract, of which 255 studies did not meet the prespecified inclusion criteria and were excluded. We screened the full texts or, if these were not available, the trial register entries, of the remaining 47 references. Reasons for exclusion at full‐text stage are listed in Characteristics of excluded studies. One ongoing study moved to awaiting classification because, although it was registered as completed, there are no data available yet (NCT04596839).

We identified six additional ongoing records (five studies: IRCT20210709051824N1; NCT04351724; NCT04843761; NCT04978259; REDPINE 2022; Characteristics of ongoing studies; Table 4). Overall, we included 60 records (nine studies) in our narrative analyses and 55 records (seven studies) in our meta‐analyses. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

2. Characteristics of ongoing studies.

| Study ID | Comparison | Aimed enrolment (n) | Expected completion date |

| NCT04252664 | Remdesivir compared to placebo | 308 | Recruiting suspended, no publication available yet |

| NCT04351724 | Remdesivir compared to standard care | NR (remdesivir arm); 500 (all study arms) |

Recruiting |

| NCT04978259 | Remdesivir compared to standard care | 202 | Recruiting |

| NCT04843761 | Remdesivir compared to placebo | 640 | Active, not recruiting |

NR = not reported

1.

Included studies

We included nine RCTs with 11,218 participants with symptomatic SARS‐CoV‐2 infection (Beigel 2020; Gottlieb 2021; Mahajan 2021; Spinner 2020; Wang 2020; WHO Solidarity Canada 2022; WHO Solidarity France 2021; WHO Solidarity Norway 2021; WHO Solidarity Trial Consortium 2022). Three studies were national add‐on trials to the WHO Solidarity Trial Consortium 2022, of which two recruited additional participants, not reported in the WHO Solidarity trial (WHO Solidarity Canada 2022; WHO Solidarity France 2021). In our meta‐analyses we only included participants of the WHO Solidarity Trial Consortium 2022, and its add‐on trials, if there was no overlap between participants.

One study was performed in an outpatient setting, including participants with mild SARS‐CoV‐2 infection (Gottlieb 2021). The other eight studies included hospitalised patients with COVID‐19. The included participants in the outpatient setting (mean age 50 years, 52.10% male), as well as the included participants in the hospitalised setting (mean age 60.9 years, 65.0% male) presented with symptomatic SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and were randomly assigned to receive either remdesivir or placebo in addition to local standard care. The majority of included studies were conducted in high‐ and upper‐middle‐income countries; the only reported lower‐middle‐income countries were Egypt, Honduras, India, and the Philippines. A detailed overview of the characteristics of included studies is provided in Characteristics of included studies and Table 5.

3. Overview of included studies.

| NA | Beigel 2020a | Spinner 2020 | Wang 2020 | WHO Solidarity Trial Consortium 2022 | Mahajan 2021 | Gottlieb 2021 | WHO Solidarity Canada 2022 | WHO Solidarity France 2021 | WHO Solidarity Norway 2021 |

| (By date of publication) | |||||||||

| Setting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Design |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Study protocol | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Not reported | Reported | Reported (WHO Trial Consortium) | Reported (WHO Trial Consortium) | Reported (WHO Trial Consortium) |

| Statistical analysis plan | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Not reported | Reported | Reported (WHO Trial Consortium) | Reported (WHO Trial Consortium) | Reported (WHO Trial Consortium) |

|

Intervention (remdesivir) (duration of application (days)) |

10 | 5 or 10 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Control | SoC | Placebo + SoC | Placebo + SoC | SoC | SoC | SoC | SoC | SoC | SoC |

| Allocated participants (n) | 1062 | 596 | 236 | 8320 | 82 | 584 | 1282 | 857 | 101 |

|

Number of participants per trial arm (allocated/evaluated) |

Intervention: 541/541 Placebo + SoC: 521/521 |

5‐day intervention: 199/191 10‐day intervention: 197/193 SoC: 200/200 |

Intervention: 158/158 Placebo + SoC: 78/78 |

Intervention: 4169/4146 SoC: 4151/4129 |

Intervention: 41/34 SoC: 41/36 |

Intervention: 292/279 Placebo: 292/283 |

Intervention: 634/634 SoC: 648/647 Participants enrolled separate from WHO Solidarity Trial : Intervention: 170 SoC: 153 |

Intervention: 429/414 SoC: 428/418 Participants enrolled separate from WHO Solidarity Trial: Intervention: 210 SoC: 207 |

Intervention: 43/42 SoC: 58/57 No participants enrolled separate from WHO Solidarity Trial |

| Severity of condition according to the level of respiratory support at baseline (n/N (%)) | |||||||||

| Ambulatory, symptomatic disease | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Intervention: 279 (100) Placebo: 283 (100) |

NA | NA | NA |

| Hospitalised, without oxygen support | Intervention: 75 (13.9) Placebo: 63 (12.1) |

Not requiring ongoing medical care 5‐day intervention: 0 (0.0) 10‐day intervention: 6 (3.2) SoC: 2 (1.0) Requiring ongoing medical care 5‐day intervention: 160 (83.8) 10‐day intervention: 163 (84.5) SoC: 160 (80.0) |

Intervention: 0 (0.0) Placebo + SoC: 3 (3.8) |

Intervention: 869 (21) SoC: 861 (20.9) |

NA | NA | Intervention: 71/634 (11.2) SoC: 54/647 (8.4) |

Intervention: 6/414 (1.4) SoC: 6/418 (1.4) |

NA |

| Low‐flow supplemental oxygen | Intervention: 232 (42.9) Placebo: 203 (39.0) |

5‐day intervention: 29 (15.2) 10‐day intervention: 23 SoC: 36 (18.0) |

Intervention: 129 (81.6) Placebo + SoC: 65 (83.3) |

Low‐flow and high‐flow oxygen Intervention: 2918 (70.4) SoC: 2921 (70.7) |

Intervention: 27 (79.4) SoC: 26 (72.2) |

NA | Intervention: 334/634 (52.7) SoC: 363/647 (56.2) |

Intervention: 247/414 (59.6) SoC: 245/418 (58.6) |

NA |

| High‐flow oxygen or non‐invasive mechanical ventilation | Intervention: 95 (17.6) Placebo: 98 (18.8) |

5‐day intervention: 2 (1.0) 10‐day intervention: 1 (0.5) SoC: 2 (1.0) |

Intervention: 28 (17.2) Placebo + SoC: 9 (11.5) |

NA | Intervention: 7 (20.6) SoC: 10 (27.8) |

NA | Intervention: 171/634 (27.0) SoC: 176/647 (27.3) |

Intervention: 86/414 (20.7) SoC: 93/418 (22.2) |

NA |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | Intervention: 131 (24.2) Placebo: 154 (29.6) |

NA | Intervention: 0 (0) Placebo + SoC: 1 (1.3) |

Non‐invasive and invasive mechanical ventilation Intervention: 359 (8.7) SoC: 347 (8.4) |

NA | NA | Intervention: 58/634 (9.1) SoC: 54/647 (8.3) |

Intervention: 75/414 (18.1) SoC: 74/418 (17.7) |

NA |

| Demographics | |||||||||

| Age (years) |

Mean (SD) Intervention: 58.6 (14.6) Placebo: 59.2 (15.4) |

Median (IQR) 5‐day intervention: 58 (48 to 66) 10‐day intervention: 56 (45 to 66) SoC: 57 (45 to 66) |

Median (IQR) Intervention: 66 (57 to 73) Placebo: 64 (53 to 70) |

n/Total < 50 Intervention: 1310 (31.6) SoC: 1326 (32.1) 50 to 69 Intervention: 1920 (46.3) SoC: 1908 (46.2) ≧ 70 Intervention: 916 (22.1) SoC: 895 (21.7) |

Mean (SD) Intervention: 58.09 (12.1) SoC: 57.41 (14.1) |

Mean (SD) Intervention: 50 (15) Placebo: 51 (15) |

Median (IQR) Intervention: 65 (53 to 77) SoC: 66 (54 to 74) |

Median (IQR) Intervention: 63 (55 to 73) SoC: 64 (54 to 72) |

Mean (SD) Intervention: 59.7 (± 16.5) SoC: 58.1 (15.7) |

| Gender (male (n(%))) | Intervention: 352 (65.1) Placebo: 332 (63.7) |