Abstract

Background

No specific antiviral drug has been proven effective for treatment of patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Remdesivir (GS-5734), a nucleoside analogue prodrug, has inhibitory effects on pathogenic animal and human coronaviruses, including severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in vitro, and inhibits Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, SARS-CoV-1, and SARS-CoV-2 replication in animal models.

Methods

We did a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial at ten hospitals in Hubei, China. Eligible patients were adults (aged ≥18 years) admitted to hospital with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, with an interval from symptom onset to enrolment of 12 days or less, oxygen saturation of 94% or less on room air or a ratio of arterial oxygen partial pressure to fractional inspired oxygen of 300 mm Hg or less, and radiologically confirmed pneumonia. Patients were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to intravenous remdesivir (200 mg on day 1 followed by 100 mg on days 2–10 in single daily infusions) or the same volume of placebo infusions for 10 days. Patients were permitted concomitant use of lopinavir–ritonavir, interferons, and corticosteroids. The primary endpoint was time to clinical improvement up to day 28, defined as the time (in days) from randomisation to the point of a decline of two levels on a six-point ordinal scale of clinical status (from 1=discharged to 6=death) or discharged alive from hospital, whichever came first. Primary analysis was done in the intention-to-treat (ITT) population and safety analysis was done in all patients who started their assigned treatment. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT04257656.

Findings

Between Feb 6, 2020, and March 12, 2020, 237 patients were enrolled and randomly assigned to a treatment group (158 to remdesivir and 79 to placebo); one patient in the placebo group who withdrew after randomisation was not included in the ITT population. Remdesivir use was not associated with a difference in time to clinical improvement (hazard ratio 1·23 [95% CI 0·87–1·75]). Although not statistically significant, patients receiving remdesivir had a numerically faster time to clinical improvement than those receiving placebo among patients with symptom duration of 10 days or less (hazard ratio 1·52 [0·95–2·43]). Adverse events were reported in 102 (66%) of 155 remdesivir recipients versus 50 (64%) of 78 placebo recipients. Remdesivir was stopped early because of adverse events in 18 (12%) patients versus four (5%) patients who stopped placebo early.

Interpretation

In this study of adult patients admitted to hospital for severe COVID-19, remdesivir was not associated with statistically significant clinical benefits. However, the numerical reduction in time to clinical improvement in those treated earlier requires confirmation in larger studies.

Funding

Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Emergency Project of COVID-19, National Key Research and Development Program of China, the Beijing Science and Technology Project.

Introduction

The ongoing pandemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infections has led to more than 4 692 797 cases and 195 920 deaths globally as of April 25, 2020.1 Although most infections are self-limited, about 15% of infected adults develop severe pneumonia that requires treatment with supplemental oxygen and an additional 5% progress to critical illness with hypoxaemic respiratory failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and multiorgan failure that necessitates ventilatory support, often for several weeks.2, 3, 4 At least half of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation have died in hospital,4, 5 and the associated burden on health-care systems, especially intensive care units, has been overwhelming in several affected countries.

Although several approved drugs and investigational agents have shown antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 in vitro,6, 7 at present there are no antiviral therapies of proven effectiveness in treating severely ill patients with COVID-19. A multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial (RCT) of hydroxychloroquine involving 150 adults admitted to hospital for COVID-19 reported no significant effect of the drug on accelerating viral clearance.8 An RCT enrolling patients within 12 days of symptom onset found that favipiravir was superior to arbidol in terms of the clinical recovery rate at day 7 in patients with mild illness (62 [56%] of 111 with arbidol vs 70 [71%] of 98 with favipiravir), but not in those with critical illness (0 vs 1 [6%]).9 In severe illness, one uncontrolled study of five patients given convalescent plasma suggested a possible benefit, although the patients already had detectable anti-SARS-CoV-2 neutralising antibodies before receipt of the plasma.10 An open-label RCT of oral lopinavir–ritonavir found no significant effect on the primary outcome measure of time to clinical improvement and no evidence of reduction in viral RNA titres compared to control.11 However, per-protocol analyses suggested possible reductions in time to clinical improvement (difference of 1 day), particularly in those treated within 12 days of symptom onset. Further studies of lopinavir–ritonavir and other drugs are ongoing.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed, up to April 10, 2020, for published clinical trials assessing the effect of remdesivir among patients with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The search terms used were (“COVID-19” or “2019-nCoV” or “SARS-CoV-2”) AND “remdesivir” AND (“clinical trial” or “randomized controlled trial”). We identified no published clinical trials of the effect of remdesivir in patients with COVID-19.

Added value of this study

Our study is the first randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial assessing the effect of intravenous remdesivir in adults admitted to hospital with severe COVID-19. The study was terminated before attaining the prespecified sample size. In the intention-to-treat population, the primary endpoint of time to clinical improvement was not significantly different between groups, but was numerically shorter in the remdesivir group than the control group, particularly in those treated within 10 days of symptom onset. The duration of invasive mechanical ventilation, although also not significantly different between groups, was numerically shorter in remdesivir recipients than placebo recipients.

Implications of all the available evidence

No statistically significant benefits were observed for remdesivir treatment beyond those of standard of care treatment. Our trial did not attain the predetermined sample size because the outbreak of COVID-19 was brought under control in China. Future studies of remdesivir, including earlier treatment in patients with COVID-19 and higher-dose regimens or in combination with other antivirals or SARS-CoV-2 neutralising antibodies in those with severe COVID-19 are needed to better understand its potential effectiveness.

Remdesivir (also GS-5734) is a monophosphoramidate prodrug of an adenosine analogue that has a broad antiviral spectrum including filoviruses, paramyxoviruses, pneumoviruses, and coronaviruses.12, 13 In vitro, remdesivir inhibits all human and animal coronaviruses tested to date, including SARS-CoV-2,13, 14, 15 and has shown antiviral and clinical effects in animal models of SARS-CoV-1 and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)-CoV infections.13, 16, 17 In a lethal murine model of MERS, remdesivir was superior to a regimen of combined interferon beta and lopinavir–ritonavir.16 Remdesivir is a potent inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 replication in human nasal and bronchial airway epithelial cells.18 In a non-lethal rhesus macaque model of SARS-CoV-2 infection, early remdesivir administration was shown to exert significant antiviral and clinical effects (reduced pulmonary infiltrates and virus titres in bronchoalveolar lavages vs vehicle only).19 Intravenous remdesivir was studied for treatment of Ebola virus disease, in which it was adequately tolerated but less effective than several monoclonal antibody therapeutics,20 and has been used on the basis of individual compassionate use over the past several months in patients with COVID-19 in some countries.21 Case studies have reported benefit in severely ill patients with COVID-19.5, 21, 22 However, the clinical and antiviral efficacy of remdesivir in COVID-19 remains to be established. Here, we report the results of a placebo-controlled randomised trial of remdesivir in patients with severe COVID-19.

Methods

Study design

This was an investigator-initiated, individually randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial to assess the effectiveness and safety of intravenous remdesivir in adults (aged ≥18 years) admitted to hospital with severe COVID-19. The trial was done at ten hospitals in Wuhan, Hubei, China).

Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review boards of each participating hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients, or their legal representative if they were unable to provide consent. The trial was done in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization–Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The protocol is available online.

Patients

Eligible patients were men and non-pregnant women with COVID-19 who were aged at least 18 years and were RT-PCR positive for SARS-CoV-2, had pneumonia confirmed by chest imaging, had oxygen saturation of 94% or lower on room air or a ratio of arterial oxygen partial pressure to fractional inspired oxygen of 300 mm Hg or less, and were within 12 days of symptom onset. Eligible patients of child-bearing age (men and women) agreed to take effective contraceptive measures (including hormonal contraception, barrier methods, or abstinence) during the study period and for at least 7 days after the last study drug administration. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy or breast feeding; hepatic cirrhosis; alanine aminotransferase or aspartate aminotransferase more than five times the upper limit of normal; known severe renal impairment (estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 mL/min per 1·73 m2) or receipt of continuous renal replacement therapy, haemodialysis, or peritoneal dialysis; possibility of transfer to a non-study hospital within 72 h; and enrolment into an investigational treatment study for COVID-19 in the 30 days before screening. The use of other treatments, including lopinavir–ritonavir, was permitted.

Randomisation and masking

Eligible patients were randomly assigned (2:1) to either the remdesivir group or the placebo group. Randomisation was stratified according to the level of respiratory support as follows: (1) no oxygen support or oxygen support with nasal duct or mask; or (2) high-flow oxygen, non-invasive ventilation, invasive ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. The permuted block (30 patients per block) randomisation sequence, including stratification, was prepared by a statistician not involved in the trial using SAS software, version 9.4. Eligible patients were allocated to receive medication in individually numbered packs, according to the sequential order of the randomisation centre (Jin Yin-tan Hospital central pharmacy). Envelopes were prepared for emergency unmasking.

Procedures

Patients received either intravenous remdesivir (200 mg on day 1 followed by 100 mg on days 2–10 in single daily infusions) or the same volume of placebo infusions for a total of 10 days (both provided by Gilead Sciences, Foster City, CA, USA). Patients were assessed once daily by trained nurses using diary cards that captured data on a six-category ordinal scale and safety from day 0 to 28 or death. Other clinical data were recorded using the WHO–International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infections Consortium (ISARIC) case record form. The safety assessment included daily monitoring for adverse events, clinical laboratory testing (days 1, 3, 7, and 10), 12-lead electrocardiogram (days 1 and 14), and daily vital signs measurements. Clinical data were recorded on paper case record forms and then double entered into an electronic database and validated by trial staff. Nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swabs, expectorated sputa as available, and faecal or anal swab specimens were collected on days 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, 14, 21, and 28 for viral RNA detection and quantification.

The trial was monitored by a contract research organisation (Hangzhou Tigermed Consulting). Virological testing was done at the Teddy Clinical Research Laboratory (Tigermed–DI'AN, Hangzhou, China) using quantitative real-time RT-PCR. RNA was extracted from clinical samples with the MagNA Pure 96 system (Roche, Rotkreuz, Switzerland), detected and quantified by Cobas z480 qPCR (Roche), using LightMix Modular SARS-CoV-2 assays (TIB MOBIOL, Berlin, Germany). At baseline, the upper (nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swabs) and lower respiratory tract specimens were tested for detection of E-gene, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene, and N-gene, then samples on the subsequent visits were quantitatively and qualitative assessed for E-gene.

Outcomes

The primary clinical endpoint was time to clinical improvement within 28 days after randomisation. Clinical improvement was defined as a two-point reduction in patients' admission status on a six-point ordinal scale, or live discharge from the hospital, whichever came first. The six-point scale was as follows: death=6; hospital admission for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or mechanical ventilation=5; hospital admission for non-invasive ventilation or high-flow oxygen therapy=4; hospital admission for oxygen therapy (but not requiring high-flow or non-invasive ventilation)=3; hospital admission but not requiring oxygen therapy=2; and discharged or having reached discharge criteria (defined as clinical recovery—ie, normalisation of pyrexia, respiratory rate <24 breaths per minute, saturation of peripheral oxygen >94% on room air, and relief of cough, all maintained for at least 72 h)=1. The six-point scale was modified from the seven-point scale used in our previous COVID-19 lopinavir–ritonavir RCT11 by combining the two outpatient strata into one.

Secondary outcomes were the proportions of patients in each category of the six-point scale at day 7, 14, and 28 after randomisation; all-cause mortality at day 28; frequency of invasive mechanical ventilation; duration of oxygen therapy; duration of hospital admission; and proportion of patients with nosocomial infection. Virological measures included the proportions of patients with viral RNA detected and viral RNA load (measured by quantitative RT-PCR). Safety outcomes included treatment-emergent adverse events, serious adverse events, and premature discontinuations of study drug.

Statistical analysis

The original design required a total of 325 events across both groups, which would provide 80% power under a one-sided type I error of 2·5% if the hazard ratio (HR) comparing remdesivir to placebo is 1·4, corresponding to a change in time to clinical improvement of 6 days assuming that time to clinical improvement is 21 days on placebo.

One interim analysis using triangular boundaries23 and a 2:1 allocation ratio between remdesivir and placebo had been accounted for in the original design. Assuming an 80% event rate within 28 days across both groups and a dropout rate of 10% implies that about 453 patients should be recruited for this trial (151 on placebo and 302 on remdesivir). The possibility for an interim analysis after enrolment of about 240 patients was included in the design if requested by the independent data safety and monitoring board.

The primary efficacy analysis was done on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis with all randomly assigned patients. Time to clinical improvement was assessed after all patients had reached day 28; no clinical improvement at day 28 or death before day 28 were considered as right censored at day 28. Time to clinical improvement was portrayed by Kaplan-Meier plot and compared with a log-rank test. The HR and 95% CI for clinical improvement and HR with 95% CI for clinical deterioration were calculated by Cox proportional hazards model. Other analyses include subgroup analyses for those receiving treatment 10 days or less vs more than 10 days after symptom onset, time to clinical deterioration (defined as one category increase or death), and for viral RNA load at entry. The differences in continuous variables between the groups was calculated using Hodges-Lehmann estimation. We present adverse event data on the patients' actual treatment exposure, coded using Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities. Statistical analyses were done using SAS software, version 9.4. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT04257656.

Results

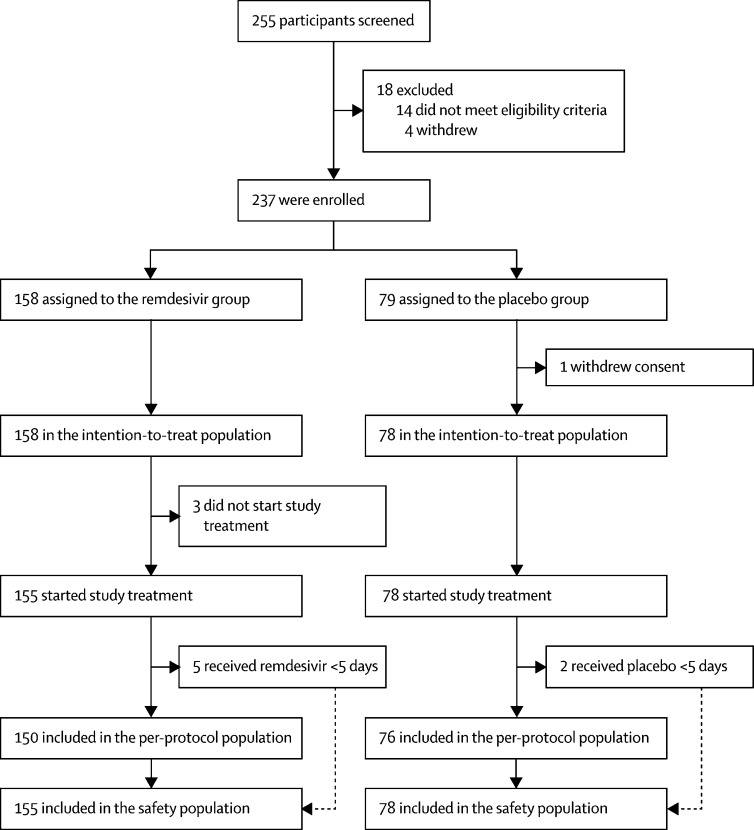

Between Feb 6, 2020, and March 12, 2020, 255 patients were screened, of whom 237 were eligible (figure 1 ). 158 patients were assigned to receive remdesivir and 79 to receive placebo; one patient in the placebo group withdrew their previously written informed consent after randomisation, so 158 and 78 patients were included in the ITT population. No patients were enrolled after March 12, because of the control of the outbreak in Wuhan and on the basis of the termination criteria specified in the protocol, the data safety and monitoring board recommended that the study be terminated and data analysed on March 29. At this stage, the interim analysis was abandoned. When all the other assumptions stayed the same, with the actual enrolment of 236 participants, the statistical power was reduced from 80% to 58%.

Figure 1.

Trial profile

Three patients in the remdesivir group did not start their assigned treatment so were not included in safety analyses (figure 1). The median age of study patients was 65 years (IQR 56–71); sex distribution was 89 (56%) men versus 69 (44%) women in the remdesivir group and 51 (65%) versus 27 (35%) in the placebo group (table 1 ). The most common comorbidity was hypertension, followed by diabetes and coronary heart disease. Lopinavir–ritonavir was co-administered in 42 (18%) patients at baseline. Most patients were in category 3 of the six-point ordinal scale of clinical status at baseline. Some imbalances existed at enrolment between the groups, including more patients with hypertension, diabetes, or coronary artery disease in the remdesivir group than the placebo group. More patients in the control group than in the remdesivir group had been symptomatic for 10 days or less at the time of starting remdesivir or placebo treatment, and a higher proportion of remdesivir recipients had a respiratory rate of more than 24 breaths per min. No other major differences in symptoms, signs, laboratory results, disease severity, or treatments were observed between groups at baseline.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Remdesivir group (n=158) | Placebo group (n=78) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 66·0 (57·0–73·0) | 64·0 (53·0–70·0) | |

| Sex | |||

| Men | 89 (56%) | 51 (65%) | |

| Women | 69 (44%) | 27 (35%) | |

| Any comorbidities | 112 (71%) | 55 (71%) | |

| Hypertension | 72 (46%) | 30 (38%) | |

| Diabetes | 40 (25%) | 16 (21%) | |

| Coronary heart disease | 15 (9%) | 2 (3%) | |

| Body temperature, °C | 36·8 (36·5–37·2) | 36·8 (36·5–37·2) | |

| Fever | 56 (35%) | 31 (40%) | |

| Respiratory rate >24 breaths per min | 36 (23%) | 11 (14%) | |

| White blood cell count, × 109 per L | |||

| Median | 6·2 (4·4–8·3) | 6·4 (4·5–8·3) | |

| 4–10 | 108/155 (70%) | 58 (74%) | |

| <4 | 27/155 (17%) | 12 (15%) | |

| >10 | 20/155 (13%) | 8 (10%) | |

| Lymphocyte count, × 109 per L | 0·8 (0·6–1·1) | 0·7 (0·6–1·2) | |

| ≥1·0 | 49/155 (32%) | 23 (29%) | |

| <1·0 | 106/155 (68%) | 55 (71%) | |

| Platelet count, × 109 per L | 183·0 (144·0–235·0) | 194·5 (141·0–266·0) | |

| ≥100 | 148/155 (95%) | 75 (96%) | |

| <100 | 7/155 (5%) | 3 (4%) | |

| Serum creatinine, μmol/L | 68·0 (56·0–82·0) | 71·3 (56·0–88·7) | |

| ≤133 | 151/154 (98%) | 76 (97%) | |

| >133 | 3/154 (2%) | 2 (3%) | |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, U/L | 31·0 (22·0–44·0) | 33·0 (24·0–48·0) | |

| ≤40 | 109/155 (70%) | 49 (63%) | |

| >40 | 46/155 (30%) | 29 (37%) | |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 26·0 (18·0–42·0) | 26·0 (20·0–43·0) | |

| ≤50 | 130/155 (84%) | 66 (85%) | |

| >50 | 25/155 (16%) | 12 (15%) | |

| Lactate dehydrogenase, U/L | 339·0 (247·0–441·5) | 329·0 (249·0–411·0) | |

| ≤245 | 36/148 (24%) | 17/75 (23%) | |

| >245 | 112/148 (76%) | 58/75 (77%) | |

| Creatine kinase, U/L | 75·9 (47·0–131·1) | 75·0 (47·0–158·0) | |

| ≤185 | 118/141 (84%) | 54/67 (81%) | |

| >185 | 23/141 (16%) | 13/67 (19%) | |

| National Early Warning Score 2 level at day 1 | 5·0 (3·0–7·0) | 4·0 (3·0–6·0) | |

| Six-category scale at day 1 | |||

| 2—hospital admission, not requiring supplemental oxygen | 0 | 3 (4%) | |

| 3—hospital admission, requiring supplemental oxygen | 129 (82%) | 65 (83%) | |

| 4—hospital admission, requiring high-flow nasal cannula or non-invasive mechanical ventilation | 28 (18%) | 9 (12%) | |

| 5—hospital admission, requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or invasive mechanical ventilation | 0 | 1 (1%) | |

| 6—death | 1 (1%) | 0 | |

| Baseline viral load of nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs, log10 copies per mL | 4·7 (0·3) | 4·7 (0·4) | |

| Receiving interferon alfa-2b at baseline | 29 (18%) | 15 (19%) | |

| Receiving lopinavir–ritonavir at baseline | 27 (17%) | 15 (19%) | |

| Antibiotic treatment at baseline | 121 (77%) | 63 (81%) | |

| Corticosteroids therapy at baseline | 60 (38%) | 31 (40%) | |

Data are median (IQR), n (%), n/N (%), or mean (SE).

Median time from symptom onset to starting study treatment was 10 days (IQR 9–12). No important differences were apparent between the groups in other treatments received (including lopinavir–ritonavir or corticosteroids; table 2 ). During their hospital stay, 155 (66%) patients received corticosteroids, with a median time from symptom onset to corticosteroids therapy of 8·0 days (6·0–11·0); 91 (39%) patients received corticosteroids before enrolment.

Table 2.

Treatments received before and after enrolment

| Remdesivir group (n=158) | Placebo group (n=78) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Time from symptom onset to starting study treatment, days* | 11 (9–12) | 10 (9–12) | |

| Early (≤10 days from symptom onset) | 71/155 (46%) | 47 (60%) | |

| Late (>10 days from symptom onset) | 84/155 (54%) | 31 (40%) | |

| Receiving injection of interferon alfa-2b | 46 (29%) | 30 (38%) | |

| Receiving lopinavir–ritonavir | 44 (28%) | 23 (29%) | |

| Vasopressors | 25 (16%) | 13 (17%) | |

| Renal replacement therapy | 3 (2%) | 3 (4%) | |

| Highest oxygen therapy support | |||

| Non-invasive mechanical ventilation | 14 (9%) | 3 (4%) | |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 11 (7%) | 10 (13%) | |

| Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or mechanical ventilation | 2 (1%) | 0 | |

| Antibiotic | 142 (90%) | 73 (94%) | |

| Corticosteroids therapy | 102 (65%) | 53 (68%) | |

| Time from symptom onset to corticosteroids therapy, days | 9 (7–11) | 8 (6–10) | |

| Duration of corticosteroids therapy, days | 9 (5–15) | 10 (6–16) | |

Data are median (IQR) or n (%).

Three patients did not start treatment so are not included in time from symptom onset to start of study treatment subgroup analyses.

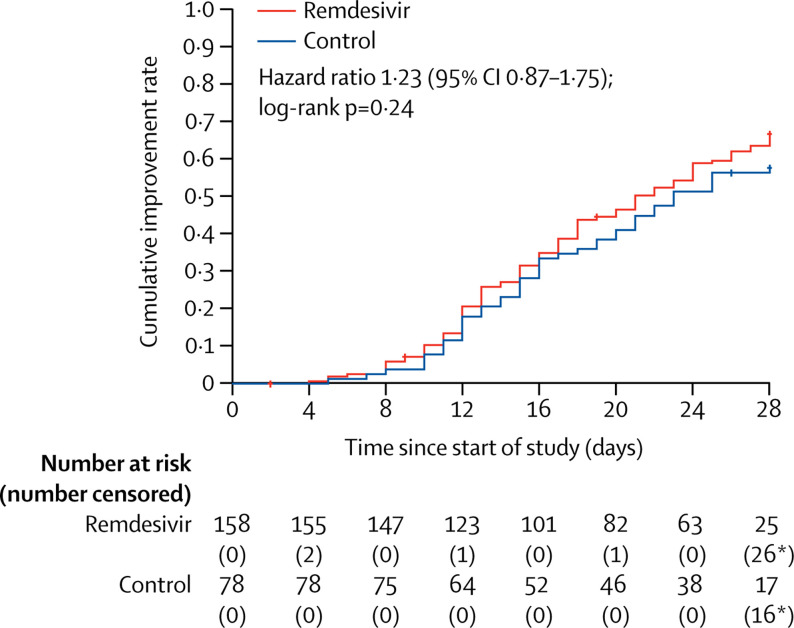

Final follow-up was on April 10, 2020. In the ITT population, the time to clinical improvement in the remdesivir group was not significantly different to that of the control group (median 21·0 days [IQR 13·0–28·0] in the remdesivir group vs 23·0 days [15·0–28·0]; HR 1·23 [95% CI 0·87–1·75]; table 3 , figure 2 ).

Table 3.

Outcomes in the intention-to-treat population

| Remdesivir group (n=158) | Placebo group (n=78) | Difference* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to clinical improvement | 21·0 (13·0 to 28·0) | 23·0 (15·0 to 28·0) | 1·23 (0·87 to 1·75)† | |

| Day 28 mortality | 22 (14%) | 10 (13%) | 1·1% (−8·1 to 10·3) | |

| Early (≤10 days of symptom onset) | 8/71 (11%) | 7/47 (15%) | −3·6% (−16·2 to 8·9) | |

| Late (>10 days of symptom onset) | 12/84 (14%) | 3/31 (10%) | 4·6% (−8·2 to 17·4) | |

| Clinical improvement rates | ||||

| Day 7 | 4 (3%) | 2 (3%) | 0·0% (−4·3 to 4·2) | |

| Day 14 | 42 (27%) | 18 (23%) | 3·5% (−8·1 to 15·1) | |

| Day 28 | 103 (65%) | 45 (58%) | 7·5% (−5·7 to 20·7) | |

| Duration of invasive mechanical ventilation, days | 7·0 (4·0 to 16·0) | 15·5 (6·0 to 21·0) | −4·0 (−14·0 to 2·0) | |

| Duration of invasive mechanical ventilation in survivors, days‡ | 19·0 (5·0 to 42·0) | 42·0 (17·0 to 46·0) | −12·0 (−41·0 to 25·0) | |

| Duration of invasive mechanical ventilation in non-survivors, days‡ | 7·0 (2·0 to 11·0) | 8·0 (5·0 to 16·0) | −2·5 (−11·0 to 3·0) | |

| Duration of oxygen support, days | 19·0 (11·0 to 30·0) | 21·0 (14·0 to 30·5) | −2·0 (−6·0 to 1·0) | |

| Duration of hospital stay, days | 25·0 (16·0 to 38·0) | 24·0 (18·0 to 36·0) | 0·0 (−4·0 to 4·0) | |

| Time from random group assignment to discharge, days | 21·0 (12·0 to 31·0) | 21·0 (13·5 to 28·5) | 0·0 (−3·0 to 3·0) | |

| Time from random group assignment to death, days | 9·5 (6·0 to 18·5) | 11·0 (7·0 to 18·0) | −1·0 (−7·0 to 5·0) | |

| Six-category scale at day 7 | ||||

| 1—discharge (alive) | 4/154 (3%) | 2/77 (3%) | OR 0·69 (0·41 to 1·17)§ | |

| 2—hospital admission, not requiring supplemental oxygen | 21/154 (14%) | 16/77 (21%) | .. | |

| 3—hospital admission, requiring supplemental oxygen | 87/154 (56%) | 43/77 (56%) | .. | |

| 4—hospital admission, requiring high-flow nasal cannula or non-invasive mechanical ventilation | 26/154 (17%) | 8/77 (10%) | .. | |

| 5—hospital admission, requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or invasive mechanical ventilation | 6/154 (4%) | 4/77 (5%) | .. | |

| 6—death | 10/154 (6%) | 4/77 (5%) | .. | |

| Six-category scale at day 14 | ||||

| 1—discharge (alive) | 39/153 (25%) | 18/78 (23%) | OR 1·25 (0·76 to 2·04)§ | |

| 2—hospital admission, not requiring supplemental oxygen | 21/153 (14%) | 10/78 (13%) | .. | |

| 3—hospital admission, requiring supplemental oxygen | 61/153 (40%) | 28/78 (36%) | .. | |

| 4—hospital admission, requiring high-flow nasal cannula or non-invasive mechanical ventilation | 13/153 (8%) | 8/78 (10%) | .. | |

| 5—hospital admission, requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or invasive mechanical ventilation | 4/153 (3%) | 7/78 (9%) | .. | |

| 6—death | 15/153 (10%) | 7/78 (9%) | .. | |

| Six-category scale at day 28 | ||||

| 1—discharge (alive) | 92/150 (61%) | 45/77 (58%) | OR 1·15 (0·67 to 1·96)§ | |

| 2—hospital admission, not requiring supplemental oxygen | 14/150 (9%) | 4/77 (5%) | .. | |

| 3—hospital admission, requiring supplemental oxygen | 18/150 (12%) | 13/77 (17%) | .. | |

| 4—hospital admission, requiring high-flow nasal cannula or non-invasive mechanical ventilation | 2/150 (1%) | 2/77 (3%) | .. | |

| 5—hospital admission, requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or invasive mechanical ventilation | 2/150 (1%) | 3/77 (4%) | .. | |

| 6—death | 22/150 (15%) | 10/77 (13%) | .. | |

Data are median (IQR), n (%), or n/N (%). Clinical improvement (the event) was defined as a decline of two categories on the modified six-category ordinal scale of clinical status, or hospital discharge. OR=odds ratio.

Differences are expressed as rate differences or Hodges-Lehmann estimator and 95% CI.

Hazard ratio and 95% CI estimated by Cox proportional risk model.

Three patients in each group were survivors and ten patients in the remdesivir group and seven patients in the placebo group were non-survivors.

Calculated by ordinal logistic regression model.

Figure 2.

Time to clinical improvement in the intention-to-treat population

Adjusted hazard ratio for randomisation stratification was 1·25 (95% CI 0·88–1·78). *Including deaths before day 28 as right censored at day 28, the number of patients without clinical improvement was still included in the number at risk.

Results for time to clinical improvement were similar in the per-protocol population (median 21·0 days [IQR 13·0–28·0] in the remdesivir group vs 23·0 days [15·0–28·0] in the placebo group HR 1·27 [95% CI 0·89–1·80]; appendix pp 2–3, 5). Although not statistically significant, in patients receiving remdesivir or placebo within 10 days of symptom onset in the ITT population, those receiving remdesivir had a numerically faster time to clinical improvement than those receiving placebo (median 18·0 days [IQR 12·0–28·0] vs 23·0 days [15·0–28·0]; HR 1·52 [0·95–2·43]; appendix p 6). If clinical improvement was defined as a one, instead of two, category decline, the HR was 1·34 with a 95% CI of 0·96–1·86 (appendix p 7). For time to clinical deterioration, defined as a one-category increase or death, the HR was 0·95 with a 95% CI of 0·55–1·64 (appendix p 8).

28-day mortality was similar between the two groups (22 [14%] died in the remdesivir group vs 10 (13%) in the placebo group; difference 1·1% [95% CI −8·1 to 10·3]). In patients with use of remdesivir within 10 days after symptom onset, 28-day mortality was not significantly different between the groups, although numerically higher in the placebo group; by contrast, in the group of patients with late use, remdesivir patients had numerically higher 28-day mortality, although there was no significant difference. Clinical improvement rates at days 14 and day 28 were also not significantly different between the groups, but numerically higher in the remdesivir group than the placebo group. For patients assigned to the remdesivir group, duration of invasive mechanical ventilation was not significantly different, but numerically shorter than in those assigned to the control group; however, the number of patients with invasive mechanical ventilation was small. No significant differences were observed between the two groups in length of oxygen support, hospital length of stay, days from randomisation to discharge, days from randomisation to death and distribution of six-category scale at day 7, day 14, and day 28 (table 3; appendix p 9).

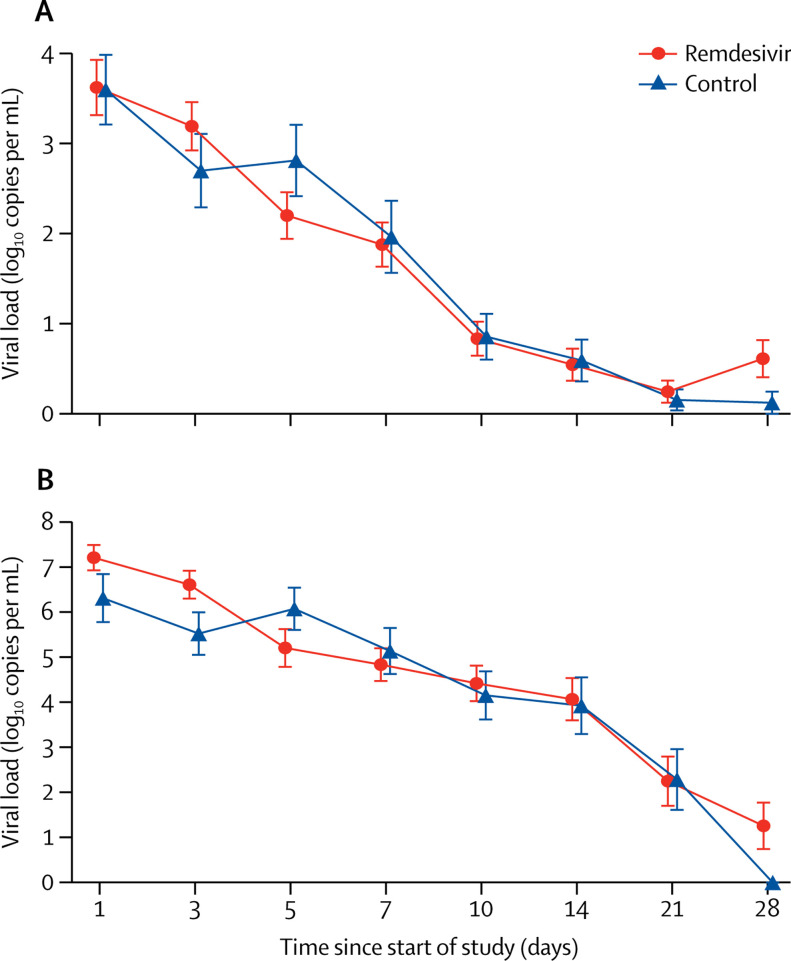

Of 236 patients (158 in the remdesivir group and 78 in the placebo group) who were RT-PCR positive at enrolment, 37 (19%) of the 196 with data available had undetectable viral RNA on the nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swab taken at baseline. The mean baseline viral load of nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs was 4·7 log10 copies per mL (SE 0·3) in the remdesivir group and 4·7 log10 copies per mL (0·4) in the control group (table 1). Viral load decreased over time similarly in both groups (figure 3A ). No differences in viral load were observed when stratified by interval from symptom onset to start of study treatment (appendix p 10). In the subset of patients from whom expectorated sputa could be obtained (103 patients), the mean viral RNA load at enrolment was nearly 1-log higher in the remdesivir group than the placebo group at enrolment (figure 3B). When adjusted for baseline sputum viral load at enrolment, the remdesivir group showed no significant difference at day 5 from placebo, but a slightly more rapid decline in load (p=0·0672).

Figure 3.

Viral load by quantitative PCR on the upper respiratory tract specimens (A) and lower respiratory tract specimens (B)

Data are mean (SE). Results less than the lower limit of quantification of the PCR assay and greater than the limit of qualitative detection are imputed with half of actual value; results of patients with viral-negative RNA are imputed with 0 log10 copies per mL.

The cumulative rate of undetectable viral RNA of nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs by day 28 was 153 (78%) of 196 patients, and the negative proportion was similar among patients receiving remdesivir and those receiving placebo (appendix p 4).

Adverse events were reported in 102 (66%) of 155 patients in the remdesivir group and 50 (64%) of 78 in the control group (table 4 ). The most common adverse events in the remdesivir group were constipation, hypoalbuminaemia, hypokalaemia, anaemia, thrombocytopenia, and increased total bilirubin; and in the placebo group, the most common were hypoalbuminaemia, constipation, anaemia, hypokalaemia, increased aspartate aminotransferase, increased blood lipids, and increased total bilirubin. 28 (18%) serious adverse events were reported in the remdesivir group and 20 (26%) were reported in the control group. More patients in the remdesivir group than the placebo group discontinued the study drug because of adverse events or serious adverse events (18 [12%] in the remdesivir group vs four [5%] in the placebo group), among whom seven (5%) were due to respiratory failure or acute respiratory distress syndrome in the remdesivir group. All deaths during the observation period were judged by the site investigators to be unrelated to the intervention).

Table 4.

Summary of adverse events in safety population that occurred in more than one participant

|

Remdesivir group (n=155) |

Placebo group (n=78) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade | Grade 3 or 4 | Any grade | Grade 3 or 4 | |

| Adverse events (in ≥2% of patients in any treatment group) | ||||

| Any | 102 (66%) | 13 (8%) | 50 (64%) | 11 (14%) |

| Hypoalbuminaemia | 20 (13%) | 0 | 12 (15%) | 1 (1%) |

| Hypokalaemia | 18 (12%) | 2 (1%) | 11 (14%) | 1 (1%) |

| Increased blood glucose | 11 (7%) | 0 | 6 (8%) | 0 |

| Anaemia | 18 (12%) | 1 (1%) | 12 (15%) | 2 (3%) |

| Rash | 11 (7%) | 0 | 2 (3%) | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 16 (10%) | 4 (3%) | 5 (6%) | 3 (4%) |

| Increased total bilirubin | 15 (10%) | 1 (1%) | 7 (9%) | 0 |

| Increased blood lipids | 10 (6%) | 0 | 8 (10%) | 0 |

| Increased white blood cell count | 11 (7%) | 0 | 6 (8%) | 0 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 10 (6%) | 0 | 8 (10%) | 0 |

| Increased blood urea nitrogen | 10 (6%) | 0 | 5 (6%) | 0 |

| Increased neutrophil | 10 (6%) | 0 | 4 (5%) | 0 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 7 (5%) | 0 | 9 (12%) | 0 |

| Constipation | 21 (14%) | 0 | 12 (15%) | 0 |

| Nausea | 8 (5%) | 0 | 2 (3%) | 0 |

| Diarrhoea | 5 (3%) | 0 | 2 (3%) | 0 |

| Vomiting | 4 (3%) | 0 | 2 (3%) | 0 |

| Reduced serum sodium | 4 (3%) | 0 | 2 (3%) | 0 |

| Increased serum potassium | 4 (3%) | 2 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 |

| Serious adverse events | ||||

| Any | 28 (18%) | 9 (6%) | 20 (26%) | 10 (13%) |

| Respiratory failure or acute respiratory distress syndrome | 16 (10%) | 4 (3%) | 6 (8%) | 4 (5%) |

| Cardiopulmonary failure | 8 (5%) | 0 | 7 (9%) | 1 (1%) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| Recurrence of COVID-19 | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cardiac arrest | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| Tachycardia | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 0 |

| Septic shock | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| Lung abscess | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| Sepsis | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| Bronchitis | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 |

| Increased D-dimer | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| Haemorrhage of lower digestive tract | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 |

| Ileus | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 0 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| Acute kidney injury | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome | 1 (1%) | 0 | 2 (3%) | 0 |

| Events leading to drug discontinuation | ||||

| Any | 18 (12%) | 3 (2%) | 4 (5%) | 1 (1%) |

| Respiratory failure or acute respiratory distress syndrome | 7 (5%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 |

| Secondary infection | 4 (3%) | 0 | 7 (9%) | 2 (3%) |

| Cardiopulmonary failure | 3 (2%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 0 |

| Nausea | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ileus | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 0 |

| Increased alanine aminotransferase | 2 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 |

| Rash | 2 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Poor appetite | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Increased total bilirubin | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Acute kidney injury | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 |

| Seizure | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 0 |

| Aggravated schizophrenia | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| Aggravated depression | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

Data are n (%) and include all events reported after antiviral treatment. Some patients had more than one adverse event. 36 patients discontinued the drug, 22 because of adverse events and 14 patients for other reasons (eg, hospital discharge or early death). COVID-19=coronavirus disease 2019.

Discussion

Our trial found that intravenous remdesivir did not significantly improve the time to clinical improvement, mortality, or time to clearance of virus in patients with serious COVID-19 compared with placebo. Compared with a previous study of compassionate use of remdesivir,21 our study population was less ill (eg, at the time of enrolment, 0·4% were on invasive mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation vs 64% in the previous study) and was treated somewhat earlier in their disease course (median 10 days vs 12 days). Such differences might be expected to favour remdesivir, providing greater effects in our study population, but our results did not meet this expectation. However, our study did not reach its target enrolment because the stringent public health measures used in Wuhan led to marked reductions in new patient presentations in mid-March, and restrictions on hospital bed availability resulted in most patients being enrolled later in the course of disease. Consequently, we could not adequately assess whether earlier remdesivir treatment might have provided clinical benefit. However, among patients who were treated within 10 days of symptom onset, remdesivir was not a significant factor but was associated with a numerical reduction of 5 days in median time to clinical improvement. Ongoing controlled clinical trials are expected to confirm or refute our findings. In one murine model of SARS, remdesivir treatment starting at 2 days after infection, after virus replication and lung airway epithelial damage had already peaked, significantly reduced SARS-CoV-1 lung titres but did not decrease disease severity or mortality.13 A need for early treatment has been found in non-human primate models of SARS and MERS in which virus replication is very short-lived and lung pathology appears to develop more rapidly than in human infections.17, 19 Such findings argue for testing of remdesivir earlier in COVID-19.

Remdesivir did not result in significant reductions in SARS-CoV-2 RNA loads or detectability in upper respiratory tract or sputum specimens in this study despite showing strong antiviral effects in preclinical models of infection with coronaviruses. In African green monkey kidney Vero E6 cells, remdesivir inhibited SARS-CoV-2 with a 50% effective concentration (EC50) of 0·46 μg/mL and an EC90 of 1·06 μg/mL.6 In human nasal and bronchial airway epithelial cells, a fixed 20 μM (12·1 μg/mL) concentration reduced estimated intracellular viral titres over 7·0 log10 50% tissue culture infective dose per mL at 48 h.18 In human airway epithelial cells, the EC50 for remdesivir was 0·042 μg/mL for SARS-CoV and 0·045 μg/mL for MERS-CoV.13 In a murine model of MERS, subcutaneous remdesivir showed significant antiviral and clinical effects with a dose regimen that maintained plasma concentrations greater than 1 μM (0·60 μg/mL) throughout the dosing interval.13 In rhesus macaques, a 5 mg/kg dose, reported to be roughly equivalent to 100-mg daily dosing in humans, was effective for treatment of MERS-CoV infection and reduced pulmonary virus replication when started at 12 h after infection.18 Healthy adult volunteers receiving doses similar to our trial (200 mg on day 1, 100 mg on days 2–4) had mean peak plasma concentrations of 5·4 μg/mL (percentage coefficient of variation 20·3) on day 1 and 2·6 μg/mL (12·7) on day 5.24 Doses of 150 mg/day for 14 days have been adequately tolerated in healthy adults, and a daily dose regimen of 150 mg for 3 days followed by 225 mg for 11 days appeared to be generally well tolerated in one patient with Ebola meningoencephalitis.25 However, the pharmacokinetics of remdesivir in severely ill patients, and particularly the concentrations of the active nucleotide metabolite (GS-441524) triphosphate in respiratory tract cells of treated patients, are unknown. Studies of higher-dose regimens for which there are safety data (eg, 150–200 mg daily doses) warrant consideration in severe COVID-19. Our study found that remdesivir was adequately tolerated and no new safety concerns were identified. The overall proportion of patients with serious adverse events tended to be lower in remdesivir recipients than placebo recipients. However, a higher proportion of remdesivir recipients than placebo recipients had dosing prematurely stopped by the investigators because of adverse events including gastrointestinal symptoms (anorexia, nausea, and vomiting), aminotransferase or bilirubin increases, and worsened cardiopulmonary status.

Limitations of our study include insufficient power to detect assumed differences in clinical outcomes, initiation of treatment quite late in COVID-19, and the absence of data on infectious virus recovery or on possible emergence of reduced susceptibility to remdesivir. Of note, in non-human primates, the inhibitory effects of remdesivir on infectious SARS-CoV-2 recovery in bronchoalveolar lavages were much greater than in controls, but viral RNA detection in upper and lower respiratory tract specimens were not consistently decreased versus controls.19 Coronaviruses partially resistant to inhibition by remdesivir (about six-times increased EC50) have been obtained after serial in vitro passage, but these viruses remain susceptible to higher remdesivir concentrations and show impaired fitness.26 The frequent use of corticosteroids in our patient group might have promoted viral replication, as observed in SARS27 and MERS,28 although these studies only reported prolongation of the detection of viral RNA, not infectious virus. Furthermore, we have no answer to whether longer treatment course and higher dose of remdesivir would be beneficial in patients with severe COVID-19.

In summary, we found that this dose regimen of intravenous remdesivir was adequately tolerated but did not provide significant clinical or antiviral effects in seriously ill patients with COVID-19. However, we could not exclude clinically meaningful differences and saw numerical reductions in some clinical parameters. Ongoing studies with larger sample sizes will continue to inform our understanding of the effect of remdesivir on COVID-19. Furthermore, strategies to enhance the antiviral potency of remdesivir (eg, higher-dose regimens, combination with other antivirals, or SARS-CoV-2 neutralising antibodies) and to mitigate immunopathological host responses contributing to COVID-19 severity (eg, inhibitors of IL-6, IL-1, or TNFα) require rigorous study in patients with severe COVID-19.

This online publication has been corrected. The corrected version first appeared at thelancet.com on May 28, 2020

Data sharing

After approval from the Human Genetic Resources Administration of China, this trial data can be shared with qualifying researchers who submit a proposal with a valuable research question. A contract should be signed.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank Gilead Sciences for providing the study drugs and Huyen Cao and Anu Osinusi for advice regarding safe use of remdesivir. We thank Joe Yao and Ella Lin for statistical consultation. We also thank members of the international data safety monitoring board (Jieming Qu [chair], Weichung Joe Shih, Robert Fowler, Rory Collins, and Chen Yao), independent statisticians (Xiaoyan Yan and Bin Shan), academic secretaries (Lingling Gao and Junkai Lai), and eDMC system providers (Tai Xie, Rong Ran, Peng Zhang, and Emily Wang) for their services. Roche Diagnostics (Shanghai) provided instruments and SARS-CoV-2 assay detection; SMO assistance was provided by Shanghai MedKey Med-Tech Development, Clinplus, Hangzhou SIMO, and MEDPISON. This work was supported by the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Emergency Project of COVID-19 (2020HY320001); Major Projects of National Science and Technology on New Drug Creation and Development (2020ZX09201012); the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFC1200102); and the Beijing Science and Technology Project (Z19110700660000). This work was also supported by the China Evergrande Group, Jack Ma Foundation, Sino Biopharmaceutical Limited, Ping An Insurance (Group), and New Sunshine Charity Foundation. TJ is funded by a National Institutes of Health Research (NIHR) Senior Research Fellowship (2015-08-001). PH is funded by the Wellcome Trust and the UK Department for International Development [215091/Z/18/Z], the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation [OPP1209135], and NIHR [200907].

Contributors

BC, CW, and YeW had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. CW and BC decided to publish the paper. BC, CW, YeW, PWH, TJ, and FGH provided input on the trial design. BC, CW, YeW, FGH, and PWH were responsible for acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. YeW, FGH, PWH, and GF drafted the manuscript. BC, CW, PWH, FGH, GF, TJ, and XG critically revised the manuscript. YeW contributed to statistical analysis. GF gave valuable suggestions for data analysis. All authors contributed to conducting the trial.

Declaration of interests

FGH has served as non-compensated consultant to Gilead Sciences on its respiratory antiviral programme, outside the submitted work. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Johns Hopkins University and Medicine COVID-19 map. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Centre. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

- 2.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. published online Feb 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhatraju PK, Ghassemieh BJ, Nichols M. Covid-19 in critically ill patients in the Seattle region–case series. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004500. published online March 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30:2–71. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu J, Cao R, Xu M. Hydroxychloroquine, a less toxic derivative of chloroquine, is effective in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro. Cell Discov. 2020;6:16. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0156-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang W, Cao Zhu, Han M. Hydroxychloroquine in patients with COVID-19: an open-label, randomized, controlled trial. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.10.20060558. published online April 14. (preprint). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen C, Huang J, Cheng Z. Favipiravir versus arbidol for COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.17.20037432. published online April 15. (preprint). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen C, Wang Z, Zhao F. Treatment of 5 critically ill patients with COVID-19 with convalescent plasma. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4783. published online March 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D. A trial of lopinavir–ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. published online March 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lo MK, Jordan R, Arvey A. GS-5734 and its parent nucleoside analog inhibit filo-, pneumo-, and paramyxoviruses. Sci Rep. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/srep43395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheahan TP, Sims AC, Graham RL. Broad-spectrum antiviral GS-5734 inhibits both epidemic and zoonotic coronaviruses. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aal3653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warren TK, Jordan R, Lo MK. Therapeutic efficacy of the small molecule GS-5734 against Ebola virus in rhesus monkeys. Nature. 2016;531:381–385. doi: 10.1038/nature17180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown AJ, Won JJ, Graham RL. Broad spectrum antiviral remdesivir inhibits human endemic and zoonotic deltacoronaviruses with a highly divergent RNA dependent RNA polymerase. Antiviral Res. 2019;169 doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2019.104541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheahan TP, Sims AC, Leist SR. Comparative therapeutic efficacy of remdesivir and combination lopinavir, ritonavir, and interferon beta against MERS-CoV. Nat Commun. 2020;11:222. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13940-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Wit E, Feldmann F, Cronin J. Prophylactic and therapeutic remdesivir (GS-5734) treatment in the rhesus macaque model of MERS-CoV infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:6771–6776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1922083117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pizzorno A, Padey B, Julien T. Characterization and treatment of SARS-CoV-2 in nasal and bronchial human airway epithelia. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.31.017889. published online April 2. (preprint). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williamson BN, Feldmann F, Schwarz B. Clinical benefit of remdesivir in rhesus macaques infected with SARS-CoV-2. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.15.043166. published online April 22. (preprint). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mulangu S, Dodd LE, Davey RT., Jr A randomized, controlled trial of Ebola virus disease therapeutics. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2293–2303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grein J, Ohmagari N, Shin D. Compassionate use of remdesivir for patients with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007016. published online April 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:929–936. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whitehead J, Stratton I. Group sequential clinical trials with triangular continuation regions. Biometrics. 1983;39:227–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilead Sciences. Investigator's brochure of remdesivir, 5th edition. Feb 21, 2020.

- 25.Jacobs M, Rodger A, Bell DJ. Late Ebola virus relapse causing meningoencephalitis: a case report. Lancet. 2016;388:498–503. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30386-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agostini ML, Andres EL, Sims AC. Coronavirus susceptibility to the antiviral remdesivir (GS-5734) is mediated by the viral polymerase and the proofreading exoribonuclease. MBio. 2018;9:e00221–e00318. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00221-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee N, Allen Chan KC, Hui DS. Effects of early corticosteroid treatment on plasma SARS-associated coronavirus RNA concentrations in adult patients. J Clin Virol. 2004;31:304–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arabi YM, Mandourah Y, Al-Hameed F. Corticosteroid therapy for critically ill patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:757–767. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201706-1172OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

After approval from the Human Genetic Resources Administration of China, this trial data can be shared with qualifying researchers who submit a proposal with a valuable research question. A contract should be signed.