Abstract

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is the causative agent of gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma and gastric cancer (GC). While this bacterium infects 50% of the world’s population, in Africa its prevalence reach as high as 80% as the infection is acquired during childhood. Risk factors for H. pylori acquisition have been reported to be mainly due to overcrowding, to have infected siblings or parent and to unsafe water sources. Despite this high H. pylori prevalence there still does not exist an African guideline, equivalent to the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report of the European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group for the management of this infection. In this continent, although there is a paucity of epidemiologic data, a contrast between the high prevalence of H. pylori infection and the low incidence of GC has been reported. This phenomenon is the so-called “African Enigma” and it has been hypothesized that it could be explained by environmental, dietary and genetic factors. A heterogeneity of data both on diagnosis and on therapy have been published. In this context, it is evident that in several African countries the increasing rate of bacterial resistance, mainly to metronidazole and clarithromycin, requires continental guidelines to recommend the appropriate management of H. pylori. The aim of this manuscript is to review current literature on H. pylori infection in Africa, in terms of prevalence, risk factors, impact on human health, treatment and challenges encountered so as to proffer possible solutions to reduce H. pylori transmission in this continent.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Africa, Risk factors, African enigma, Prevalence, Treatment, Diagnosis

Core tip: Africa has the highest rates of global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection worldwide. Nevertheless, scarce data are available, describing in some cases both inappropriate diagnostic approaches and therapeutic regimens. This probably depends on the lack of continental consensus guideline for the management of H. pylori infection. As a consequence, there is an increasing number of papers reporting, in several countries, a high rate of bacterial resistance to the most commonly used antibiotics for H. pylori treatment. This manuscript gives an update on the African literature about H. pylori infection and on the present and future challenges in this context.

IMPACT OF HELICOBACTER PYLORI INFECTION ON HUMAN HEALTH

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is mostly asymptomatic in its carriers, but when it affects human health, gastritis, gastric ulcers and duodenal ulcers (DU) can be induced. About 90% to 100% of all DU and 70% to 80% of all gastric ulcers are caused by H. pylori infection[1,2]. After bacterial eradication the recurrence rate of peptic ulcer is dramatically reduced to 5%-10%[3]. In 1994, The International Agency for Research on Cancer, an arm of the World Health Organization classified H. pylori as a class I carcinogen for gastric cancer (GC), a definition given for the highest cancer causing agent[4]. As a consequence, H. pylori eradication has also been identified and adopted from several studies as a potential strategy for the primary prevention of GC[5]. Thereafter, H. pylori was identified as the causative agent of mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma[6].

Beyond its role in several gastroduodenal disorders, H. pylori has been involved in many extra-gastroduodenal manifestations, like idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, cardiovascular diseases, chronic liver diseases, iron-deficiency anaemia, and diabetes mellitus (DM)[7-9]. However, the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report of the European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group actually consider causal association with H. pylori only in the case of unexplained iron-deficiency anemia and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura[10]. Our objective was to review the current literature on H. pylori prevalence, impact on human health, treatment and challenges encountered in Africa.

On the bases of our aim, the main inclusion criteria of the articles considered were that these must have been published within 10 years (from 2009 onwards), that they were published in peer-reviewed journals and in English language and that they were performed on Africans, resident/located in Africa. Articles not meeting these inclusion criteria were excluded. Also, articles published as correspondence, letters, and conference proceedings were not considered. When no article was found in a particular African region, an exception of extending the publication year for more than 10 years was made. The search databases included MEDLINE, PUBMED, Web of Science, Scopus, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Google scholar.

PREVALENCE OF HELICOBACTER PYLORI IN AFRICA

There is a huge paucity of data on H. pylori prevalence in the general population across different regions of Africa. The majority of data published on the prevalence of H. pylori included patients presenting with symptoms of gastroduodenal diseases. H. pylori infects over 50% of the world’s population. The distribution of H. pylori is influenced by age, sex, geographical location, ethnicity, and socio economic factors[11-13]. The geographical distribution of H. pylori shows higher prevalence in the developing countries when compared to the developed countries especially in younger ages. With a majority of countries in Africa, classified as developing or underdeveloped, H. pylori is therefore mainly ubiquitous in this continent.

A systematic review with meta-analysis, carried out by Hooi et al[11], included 184 studies, from 62 different countries, published between 1970 to 2016 on the prevalence of H. pylori infection and its worldwide distribution. Africa had the highest rate of H. pylori infection with a prevalence of 70.1%, followed by South America and Western Asia with prevalence of 69.4% and 66.6%, respectively. The authors reported that Nigeria had the highest H. pylori prevalence at 87.7% followed closely by Portugal and Estonia with a H. pylori prevalence of 86.4% and 82.5%, respectively[11]. In contrast, Zamani et al[13] in a recent meta-analysis evaluating the global prevalence of H. pylori infection found Latin America and the Caribbean to have the highest prevalence of H. pylori worldwide with a prevalence of 59.3%. Nevertheless, these authors also reported that Nigeria had the highest prevalence of H. pylori infection with a rate of 89.7%. The high prevalence of H. pylori in Africa is presumed to be influenced by sociodemographic and geographical factors[14].

In Rwanda, Southern Africa, Walker et al[15] reported 75% positivity rate to H. pylori in patients attending the University Hospital Butare over a period of 12 mo, which was found to be similar to the prevalence of other sub-Saharan African countries. A study on genomic evolution H. pylori in two South African families revealed that transmission episodes were significantly more frequent between individuals living in the same house and close relatives, however transmission did not always occur within families[16]. Comparing horizontal and familial transmission of H. pylori in Africa, Schwarz et al[17] reported that horizontal transmission occurred often between persons who do belong to a core-family, hence tainting the typical pattern of familial transmission in developed countries. This is substantiated by the work of Nell et al[18], from Central Africa who reported the acquisition of H. pylori by Baka pygmies of Cameroon through secondary contact with their non-Baka agriculturist neighbours. The prevalence rate of H. pylori infection amongst asymptomatic patients from Harare, Zimbabwe was 67.7%[19].

In Northern Africa, a recent study in Egypt compared the prevalence of H. pylori antibodies in patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura and in the general Egyptian population[20]. Seropositivity of anti-Helicobacter IgM was higher in the general population (54.4%) when compared with patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (28.9%). Also, seropositivity of anti-Helicobacter IgG was higher in the general population (79.8%) when compared with the controls[20]. In Morocco, Bounder et al[21] assessed H. pylori prevalence in subjects with and without symptoms of gastric disorders. The authors reported an overall H. pylori seropositivity prevalence of 92.6% among asymptomatic Moroccans and 89.6% among patients with gastric disorders.

In Eastern Africa, a study from Kenya, among patients who presented with dyspepsia, showed a prevalence of H. pylori infection of 73.3% in children vs 54.8% in adults[22]. Taddesse et al[23] reported a H. pylori prevalence of 53% in dyspeptic patients in Addis Ababa with an estimated prevalence peak in patients aged between 54-61 years. Another study by Hestvik et al[24], in Uganda, reported a prevalence of 44.3% of H. pylori in healthy children aged 0-12 years, with identified factors of increased infection risk including source of drinking water, use of pit latrine and wealth index driving transmission. These factors coupled with re-crudescence or reinfection from multiple sources accounts for the continuous high prevalence of H. pylori infection in Africa[25]. Though the route of transmission of this infection is not well established; possible routes of transmission such as person-person, oral-oral and faecal-oral have been suggested. The ability of the pathogen to survive for some days in water buttressed the fact of possible water transmission[26,27].

Melese et al[28] evaluated the prevalence of H. pylori in Ethiopia by different studies carried out on different populations and different geographical areas of the country. The results of their meta-analysis showed an overall pooled prevalence of H. pylori as 52.2%. The authors also reported that the prevalence of H. pylori was highest in Somali (71%) and lowest in Oromia (39.9%).

In Nigeria, West Africa, the issue of differing prevalence based on geographical location was encountered. Aje et al[29], in a study conducted in south-west Nigeria, on dyspeptic patients, reported a 67.4% prevalence of H. pylori. In a similar study, Jemilohun et al[30] in Ibadan, reported a prevalence of 63.5% in patients with gastritis. However, Etukudo et al[31] in a study from Uyo, south-south Nigeria, reported a lower seroprevalence rate (30.9%) in children with a peak (40.7%) for the 6-10 years age group. Factors associated with high seroprevalence were increased household population (P = 0.009), source of drinking water (P = 0.014), low social class (P = 0.038), type of convenience used (P = 0.019) and method of household waste disposal (P = 0.043).

Ophori et al[32], including healthy volunteers in Delta State in South South Nigeria, reported a prevalence of H. pylori infection of 89.7% in their study population. Ishaleku and Ihiabe reported a H. pylori infection prevalence of 54% amongst healthy university students in Nassarawa state, North Central Nigeria[33]. In contrast, Ezeigbo and Ezeigbo reported 39.7% H. pylori prevalence amongst apparently healthy adults residing in Aba, Abia State, South Eastern Nigeria[34]. A current report on the prevalence of H. pylori from patients with and without type 2 DM in South West and South South Nigeria showed a prevalence of 68.4% amongst those with type 2 DM[35].

Awuku et al[36], using a lateral flow immunochromatographic assay for the qualitative detection of H. pylori antigen in a fecal specimen, reported a prevalence of H. pylori of 14.2% among asymptomatic children in a rural setting in Ghana. Table 1 shows the prevalence rate of H. pylori in Africa. An observation reported in all African studies was that H. pylori prevalence increased with age and that factors such as location, access to potable water and hygiene, and socio-economic status influenced the variability seen in H. pylori prevalence within and between countries.

Table 1.

Prevalence rate of Helicobacter pylori in Africa

| Region | Included sample | Prevalence (%) | Ref. |

| North Africa | |||

| Morocco | Asymptomatic | 92.6 | [21] |

| Gastric disorder | 89.6 | ||

| Egypt | 1General | 79.8 | [20] |

| West Africa | |||

| Nigeria | 1General | 87.7-89.7 | [11,13] |

| Ghana | Children | 14.2 | [36] |

| East Africa | |||

| Ethiopia | Dyspeptic | 52.2-53.0 | [23] |

| Kenya | Children | 73.3 | [22] |

| Adults | 54.8 | ||

| Uganda | Children | 44.3 | [24] |

| Southern Africa | |||

| South Africa | Gastric related morbidities | 66.1 | [16] |

| Rwanda | 1General | 75.0 | [16] |

| Zimbabwe | Asymptomatic | 67.7 | [19] |

General: People chosen without stating whether symptomatic or asymptomatic.

Helicobacter pylori and socio-economic status

A study from Zambia, Southern Africa, performed by McLaughlin et al[37] showed no correlation between H. pylori infection and socio-economic factors. In Kano, North-West Nigeria, Bello et al[38] showed high prevalence of H. pylori particularly amongst subjects with low socioeconomic status. Factors such as unclean water source, overcrowding and cigarette smoking were significant risk factors for H. pylori infection. In contrast, in a study from South–West Nigeria, Smith et al[39] reported that most characteristics studied such as smoking, alcohol consumption and sources of drinking water were not significantly associated with H. pylori. Rather, prior antibiotic use, overcrowding, having siblings/parents with history of ulcer/gastritis had significant association. Thus, overcrowding was the main common risk factor in both studies in Nigeria.

These reports were also corroborated by Aguemon et al[40] in a study performed in Benin republic, Western African too, who reported that overcrowding and family contact with infected persons were as-sociated risk factors for H. pylori acquisition and slightly in support of these findings were reports from Cameroon, Central Africa, by Kouitcheu Mabeku et al[41] where risk factors for H. pylori acquisition were low income and family history of GC.

A study from Ghana showed that low socio-economic class and farming profession accounted for higher H. pylori prevalence[25]. Another study from the same country, including children, reported increasing household numbers, open-air defaecation and other sources of drinking water with the exception of pipe and borehole as risk factors of H. pylori[36]. A study from Egypt, Northern Africa, by El-Sharouny et al[42] reported the isolation of H. pylori from drinking water by culture and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) although at low prevalence (3.8%).

PECULIARITY OF THE IMPACT OF H. PYLORI INFECTION ON HUMAN HEALTH IN AFRICA (THE AFRICAN ENIGMA)

The natural history of H. pylori in Africa seems to differ from those in the developed countries. In fact, in this continent, the most common gastroduodenal disease associated with H. pylori infection is gastritis. Kuipers and Meijer[43] suggested that the progression of H. pylori infection to atrophic gastritis in the African population is quite similar to that reported in the Western countries or other regions, but unidentified factors could inhibit the evolution to GC. As a consequence, despite the worldwide reported association between gastric adenocarcinoma and H. pylori, the development of this malignancy is rare in Africans, a phenomenon that has been referred to as the “African enigma”[44]. This occurs even when risk factors (positivity for cagA and vacA genes) for development of cancers are ubiquitous in H. pylori isolates of African origin[45].

The term “African Enigma” was first coined by Holcombe describing the phenomenon of high prevalence of H. pylori in Africa but without a corresponding severe pathology such as GC[46]. According to this observation is the fact that the infection has different patterns from that of the Western countries, in term of age of acquisition, environmental and dietary factors, and genetics. Holcombe identified gastritis as the main health problem caused by H. pylori infection in Africa and this has been largely confirmed[46].

In Northern Africa, despite the scarcity of publications on H. pylori prevalence among patients with gastroduodenal diseases or in the general population, the few studies showed that gastritis was the most common disease associated with H. pylori infection followed by peptic ulcer. In Morocco, Boukhris et al[47] found a significant association between H. pylori infection and gastritis followed by that with peptic ulcer disease, but no significant association was seen between H. pylori and GC. Similarly, in the same country, Bounder et al[21] found chronic gastritis as the most gastric disease associated with H. pylori infection[21]. In Egypt, although GC is rare, studies with small sample size including patients with GC, found the presence of H. pylori in all cases[48,49]. Thus, this contrasts with the above-suggested pattern but the above reported limitation could explain the difference with the general literature.

In Eastern Africa, gastritis was the most reported common disease associated with H. pylori infection[50-52]. In Ethiopia, Alebie and Kaba found a high prevalence of H. pylori infection (71.0%) among students with gastritis[53]. Ayana et al[50], in Tanzania, reported the prevalence of H. pylori in patients with gastroduodenal disorders. In this cohort, the authors found gastritis (61.1%), gastroesophageal reflux disease (57%), peptic ulcer disease (24.1%), and GC (6.7%). However, only gastritis and DU were significantly associated with H. pylori infection. Similarly, Oling et al[51], in a tertiary hospital that served both Kenyans and Ugandans, evaluated the prevalence of H. pylori in dyspeptic patients. The authors found chronic non-active gastritis as the most common gastroduodenal disorder and reported a strong association between gastritis and DU with H. pylori.

There are scarce data on the prevalence of H. pylori infection among patients with gastroduodenal diseases or the general population in Central Africa. The majority of the current articles on H. pylori were reported from Cameroon, and similarly to the African literature, a strong association between gastritis and H. pylori was found. Ankouane et al[53] observed in their study that 71.2% of patients with atrophic gastritis were positive for H. pylori infection. The authors also found a statistically significant association between the severity of atrophic gastritis and H. pylori infection. This result was corroborated by Ebule et al[54] also in Cameroon, who reported that 72.8% of patients with superficial gastritis were infected with H. pylori.

In Ghana, Western Africa, a study by Afihene et al[55] found that the most common ailment among patients with gastroduodenal disorders was gastritis. However, the authors observed that the only gastroduodenal disorder significantly associated with H. pylori infection was DU. Similarly, Darko et al[56], even in Ghana, found gastritis and DU as the two most common endoscopic findings in patients with H. pylori infection. In Nigeria, Harrison et al[57] found a significant correlation between H. pylori infection (identified by urea breath test) and chronic gastritis but did not find such association with other disease outcomes.

Tanih et al[58], in the Eastern Cape Province of Southern Africa, reported that the prevalence of H. pylori, in patients suffering from gastric-related morbidities, was 66.1% and highest in patients with nonulcer dyspepsia. Though the pathogenicity of the circulating H. pylori strain may influence its clinical manifestation, nonetheless, mild pathogenicity and low incidence of GC in Africa is recorded even in the face of high prevalence of highly pathogenic H. pylori strains[57]. This further corroborates the African enigma. Probably, the latter results from a combination of three major causes: The cancer cause potential of the specific strains of H. pylori, the modulation by coinfections of the immune response towards a Th-2 type, and the preponderance of antioxidants in the diet. In the traditional epidemiologic model the combination of these factors forms a web of causation whose dynamics most likely differs in the groups where the enigma has been reported. The modulation of the immune system by coinfections, such as with helminthes, plays a prominent role influencing the impact of H. pylori infection[59].

CHALLENGES ON THE PREVALENCE OF HELICOBACTER PYLORI IN AFRICA

Some of the challenges in estimating the prevalence of H. pylori in Africa have already been mentioned above. Prevalence of H. pylori is variable within and between countries, different population groups, and the testing method used[60]. Problems of paucity of data or lack of recent articles, even in the last ten years were encountered for some regions in Africa. Studies such as the meta-analysis by Melese et al[28] identified that, in Ethiopia, despite the high prevalence of H. pylori there was a decreasing pattern in the trend of infection over the years[28]. Hence, using such old data for some African regions may not provide a good representative of the current prevalence of H. pylori in such regions and in the continent.

Another challenge faced in reporting the prevalence of H. pylori in Africa is that a majority of the studies focused on patients with symptoms of gastroduodenal disease. Considering that H. pylori has been identified as the main causative organism for gastric disorders, using data from such studies would overestimate the prevalence of H. pylori in Africa. Even studies that evaluated the prevalence of H. pylori in asymptomatic people were hospital-based cross-sectional studies and not community studies or population data. Carrying out a random selection of people in the community or even cross-sectional studies of people in the different African regions will provide a more accurate prevalence of H. pylori in Africa.

Another major challenge in estimating the prevalence of H. pylori in Africa is the different choice of the screening test used to identify the presence of the bacterium. A majority of the studies used blood serology to test for antibodies against H. pylori. This greatly influenced the estimated prevalence of H. pylori in Africa. In fact, according to Hanafi et al[20] getting a positive result when testing for the presence of H. pylori antibodies in the blood or serum does not distinguish between previous contact and active infection.

Several studies comparing the use of different tests on the estimated prevalence of H. pylori infection showed that the method significantly affects the prevalence of H. pylori infection. Asrat et al[61] compared H. pylori culture, rapid urease test, PCR-denaturing gel electrophoresis, histopathology, silver staining, stool antigen test and enzyme immunoassay assay. The authors found that H. pylori infection prevalence varied significantly based on the detection method used. They reported a prevalence of 69%, 71%, 91%, 81%, 75%, 81% and 80% using culture, rapid urease test, PCR-denaturing gel electrophoresis, histopathology, silver staining, stool antigen test and enzyme immunoassay assay, respectively[61]. Similar disparities was seen in the study by Harrison et al[57] with varying results using urea breath test, culture and a rapid urease test. Seid and Demsiss compared the stool antigen test with a serum anti-H. pylori IgG test. The authors found a detection rate of 30.4% and 60.5%, respectively[60].

Another challenge that affects estimating the prevalence of H. pylori infection in Africa is its dynamics. In most Western countries, H. pylori infection prevalence reduces with age. However, this has not been documented in most African countries where the reverse has been observed. Some of the studies found on the prevalence of H. pylori in asymptomatic patients or done in the community focused on children[36]. Melese et al[28], in their systematic review and meta-analysis, noted that in Ethiopia the prevalence of H. pylori increased with age[28]. A similar trend was reported by Mungazi et al[19] in Zimbabwe. This could reflect the so-called cohort-effect but considering that the prevalence of H. pylori may change from childhood to adulthood, using reports on a population group may under or overestimate the real epidemiology in that region.

TREATMENT OF H. PYLORI IN AFRICA: THE ACTUAL SCENARIO

Literature data recommend the use of a combination of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and antimicrobials to treat H. pylori. The Maastricht V Consensus Report recommends that the first-line regimen should be based on PPI drugs, clarithromycin and amoxicillin or metronidazole for 14 d in regions with low clarithromycin resistance. In areas where a resistance rates of over 15%-20% for clarithromycin is recorded, the bismuth-containing quadruple therapy or concomitant therapy (including 3 antibiotics and a PPI) are recommended. Second line treatment should be based on the need to carry out an endoscopy. When this approach is requested, culture and standard antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) should be performed to lead to the more appropriate therapy. When endoscopy is not requested or is not possible, the rationale of the second-line treatment is to drop the empirical use of clarithromycin, due to the high possibility that strains of H. pylori-resistant to clarithromycin have developed. The use of levofloxacin-containing triple therapy, as a rescue therapy following the failure of the standard triple therapy, is a reasonable alternative when local fluoroquinolone resistance is < 10%. Third line therapy should be guided by AST only[10].

In Africa, there are no guidelines addressing H. pylori treatment in all countries of the continent. Nevertheless, the actual African scenario is enriched year by year by publications reporting the results of randomized clinical trials (RCT) or real-world data as well as the results of microbiological and genotypic analysis of bacterial resistance to antimicrobials.

STUDIES ON CLINICAL EFFICACY OF ANTIMICROBIALS FOR H. PYLORI ERADICATION IN AFRICA

The African pattern of H. pylori eradication rates could be described analyzing the macro-regions of this continent. In Tunisia, North Africa, the eradication rate has been reported significantly higher among patients treated by omeprazole, amoxicillin and clarithromycin (69.6%) compared to those treated with omeprazole, amoxicillin and metronidazole (48.7%)[62]. In Morocco, the results of two clinical trials based on the treatment with a clarithromycin-based triple therapy, indicated a high rate of H. pylori-resistance to clarithromycin. The first showed an eradication rate inferior than 80% [intention to treat (ITT) analysis: 78.2; per protocol (PP) analysis: 79.6][63]. The second showed a reduction in terms of eradication rates obtained by this regimen (ITT: 65.9; PP: 71)[64], indirectly suggesting an increased resistance rate to clarithromycin.

In Egypt, an attempt to found new antibiotic regimens has been reported. Two hundred and 24 patients with dyspeptic symptoms and H. pylori–infection were enrolled in a randomized study. Patients in group 1 received nitazoxanide (an antibiotic with characteristics similar to metronidazole) 500 mg twice daily, cla-rithromycin 500 mg twice daily, and omeprazole 40 mg twice daily for 14 d. Patients in group 2 received metronidazole 500 mg twice daily, clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily, and omeprazole 40 mg twice daily for 14 d. To assess the eradication rate, the stool antigen test was performed 6 wk after cessation of these treatments. The eradication rate was significantly higher in group 1 than in group 2. According to PP analysis, 106 cases (94.6%) of 112 patients who completed the study in the former group obtained complete cure vs 60.6% of 104 patients who completed the study in group 2, (P < 0.001). Thus, nitazoxanide is a promising antibiotic for the first-line therapy of H. pylori eradication[65].

In Nigeria, West Africa, a RCT comparing a 7-d vs a 10-d regimen of rabeprazole, amoxicillin and clarithromycin was carried out in 50 H. pylori positive patients with several gastroduodenal symptoms. The average eradication rate was 87.2% without significant difference between the two regimens[66].

In Kenya, East Africa, a RCT including 120 H. pylori positive dyspeptic patients, compared the efficacy of a 7-d vs a 14-d regimen using esomeprazole, amoxicillin and clarithromycin. The eradication rates, according to the ITT analysis, were 76.7% and 73.3% for 7 and 14 d respectively, while the eradication rates by PP analysis were 92% and 93.6% for 7 and 14 d, respectively. Thus, there was no significant difference between these two regimens[67].

In Rwanda, Central Africa, Kabakambira et al[68] conducted a RCT from November 2015 to October 2016. The authors enrolled 299 dyspeptic patients with several gastroduodenal diseases and H. pylori infection. All subjects were randomized to either a triple therapy, for 10 d, containing omeprazole, amoxicillin and one among clarithromycin/ciprofloxacin/metronidazole or a quadruple therapy containing omeprazole, amoxicillin, ciprofloxacin and doxycycline. The rate of H. pylori eradication was 80% in the total population and 78% in patients without a history of previous triple therapy treatment. Considered globally, the results showed a higher risk of failure in the metronidazole-based group although this was insignificant (36%, P = 0.086).

STUDIES ON LABORATORY-BASED ANTIMICROBIAL RESISTANCE OF H. PYLORI IN AFRICA

Antimicrobial resistance of H. pylori is a key factor associated with eradication failure. The prevalence of such resistance varies amongst different geographical areas and has increased globally.

Focusing on North Africa, in Egypt AST showed high phenotypic metronidazole resistance (100%) of H. pylori to metronidazole and low resistance to other tested antimicrobials[69]. Recently, the Cairo’s University Hospital investigated the same issue, using molecular methods, in a study including 70 H. pylori positive biopsies of patients never treated for this infection. In 62.9% of the samples, the rdxA gene deletion (marker of metronidazole re-sistance) was detected, while analyzing the H. pylori 23S rRNA V domain, the A2142G mutation (marker of clarithromycin resistance) was shown in 55.7% of the cases[70]. The difference of results between these two studies may be explained by at least two factors. The first is the different age of patients included. In the latter, patients were > 18 years old while in the former patients were 2-17 years old, a group at higher risk of exposition to metronidazole for the treatment of parasitic infections. The second factor is the method used. In fact, in the former study the antibiotic resistance was evaluated by culture and in vitro AST[69], a method that have the tendency to overestimate resistance. In the latter study, metronidazole resistance was detected through genetic analysis[70]. In Tunisia, using both E-test and real-time PCR with Scorpion primers, resistances to clarithromycin and metronidazole were 15.4% and 51.3% respectively, with 0% resistance to amoxicillin. No discrepancy between the two methods was reported[71]. In Algeria, the prevalence of H. pylori resistance to clarithromycin was 33%[72]. In another study, in the same country, H. pylori isolates were sensitive to amoxicillin, tetracycline, rifampicin, but exhibited a high rate of resistance to metronidazole (61.1%) and a lower rate of resistance to clarithromycin (22.8%) and ciprofloxacin (16.8%). There was no statistically significant relationship found between vacA and cagA genotypes and antibiotic resistance results with the exception of metronidazole, for which there was a statistically significant relationship with cagA genotype (P = 0.001)[73]. In another prospective study carried out in Algeria between November 2015 and August 2016, isolation of H. pylori by culture was performed on antral and fundic gastric biopsies of adult patients from 3 hospitals. Additionally, real-time PCR using the fluorescence resonance energy transfer principle for the detection of H. pylori followed by a melting curve analysis to detect mutations associated with resistance to clarithromycin was employed. The prevalence of H. pylori infection was 57% using this technique with primary and secondary resistance rates to clarithromycin being 23% and 36%, respectively, and to metronidazole, 45% and 71%, respectively. All isolates were sensitive to amoxicillin, tetracycline, and rifampicin while only one isolate was resistant to levofloxacin[74]. In a study from Morocco, the primary resistance of H. pylori to clarithromycin was 28.2%. It was noted that women more often than men were infected with a resistant strain of H. pylori (38% vs 18%, P = 0.044). Using Scorpion PCR among 22 biopsies positive for H. pylori, 15 (68%) harbored an A2142G mutation, 6 (27%) an A2143G mutation, and 2 (9%) an A2142C mutation. The remaining H. pylori positive biopsy harbored a mixture of both A2142G and A2143G mutations. In 16 (77%) biopsies, a mixed infection with a susceptible and a resistant strain was reported[75].

Hence, considering that the resistance rate to clarithromycin is largely over the 15%-20% threshold put forward by the Maastricht V Consensus Report[10], it is appropriate to quit the clarithromycin-based treatment as a first-line strategy in several areas of North Africa.

In Senegal, West Africa, it was reported that the bacterial isolates showed a high rate of resistance to metronidazole (85%), low rate of resistance to clarithromycin (1%), and no resistance to amoxicillin and tetracycline[76]. In another study from Senegal, H. pylori resistance to metronidazole ranged from 85%-90%, that of clarithromycin ranged from 0-1% and the reported susceptibility to amoxicillin and ciprofloxacin was 100%[77]. In Nigeria, Aboderin et al[78] in the year 2007 reported multiple H. pylori resistance to amoxicillin (100%), clarithromycin (100%) and metronidazole (100%), as determined by disc diffusion test. Resistance to rifampicin, tetracycline and ciprofloxacin were 93.5%, 87.1% and 15.6% respectively. A total of 5 distinct antibiograms were encountered in the 32 H. pylori strains and the patterns varied with resistance ranging from 4 to 6 antimicrobial agents. Interesting, the profile of ciprofloxacin resistance was significantly different from that reported in 2005, when 0% of resistance was published by Albdulrasheed et al[79]. Another Nigerian study, published in 2017, reported by phenotypic evaluation a high resistance rate to metronidazole (99.1%), and decreasing resistance rates to amoxicillin (33.3%), clarithromycin (14.4%) and tetracycline (4.5%)[57]. In Gambia, using DNA transformation and sequencing, Secka et al[80] investigated the role of the gene rdxA in metronidazole susceptibility. Metronidazole-resistant strains of H. pylori were rendered metronidazole susceptible by transformation with a functional rdxA gene; conversely, metronidazole-susceptible strains were rendered metronidazole resistant by rdxA inactivation. RdxA sequencing revealed many mutations amongst their H. pylori strains, which probably explains inactivation of rdxA in metronidazole-resistant strains. None of the isolates were resistant to cla-rithromycin and erythromycin while amoxicillin and tetracycline resistances were rare. These data suggest that in Gambia, the use of metronidazole-based therapies for H. pylori eradication should be considered with caution[80].

In Congo, Central Africa, by using molecular methods, H. pylori resistance to clarithromycin and tetracycline were surprisingly low (1.7 and 2.5% respectively) but a high rate of resistance (50%) to fluoroquinolones was reported[81]. A study from Cameroon reported high resistance rates to tetracycline, clarithromycin and metronidazole (44.7%, 85.6% and 93.2%, respectively)[82]. In Uganda, analyzing by molecular methods stool samples of patients with peptic ulcer disease, among samples positive for H. pylori infection, 29% were resistant to clarithromycin and 42% to fluoroquinolones[83].

In East Africa, H. pylori strains had resistance rates of 0-6.4% to clarithromycin, 0-6% to amoxicillin, 0-1.9% to tetracycline but had 4.6% to 100% resistance to metronidazole[22,84,85]. Hence, in these countries a clarithromycin-based therapy could represent an appropriate therapeutic strategy.

In South Africa, H. pylori resistance rates were 0% for ciprofloxacin, 2.5% for amoxicillin, 20% and 27.5% for clarithromycin and gentamicin, while the resistance rate to metronidazole was very high (95.5%)[86]. The antibiotic resistance profile changed analyzing data region by region and over the time. In another study, published 3 years after, the same group reported a similar H. pylori resistance to clarithromycin (15.3%) but a higher resistance rate (10.2%) to fluoroquinolones[87].

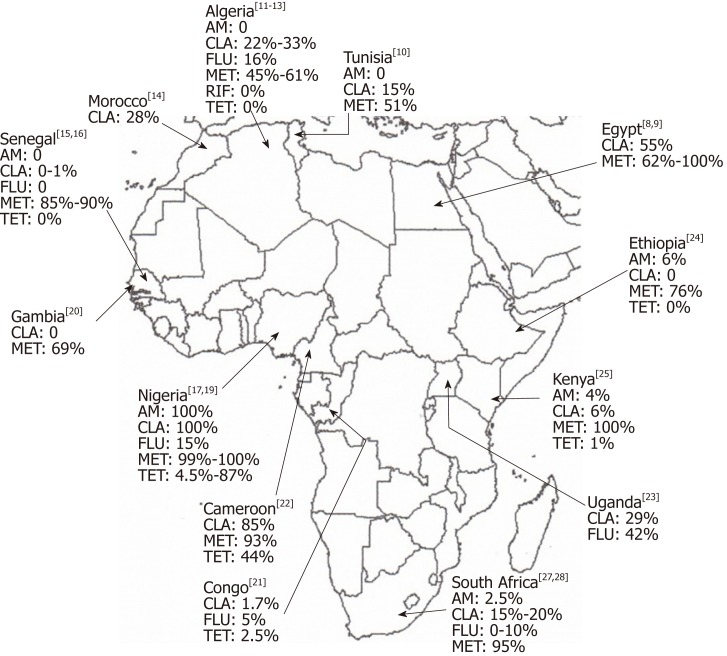

Finally, in a systematic review with meta-analysis Jaka et al[88] investigated the magnitude of H. pylori antibiotic resistance in Africa. Considering 26 articles, the overall H. pylori resistance rates to fluoroquinolones, clarithromycin, tetracycline, metronidazole and amoxicillin were: 17.4%, 29.2%, 48.7%, 75.8%, and 72.6%, respectively. As expected, the commonest mutation detected for resistant strains were A2143G for clarithromycin, RdxA for metronidazole and D87I for fluoroquinolones. Figure 1 shows an overview of the laboratory-based antimicrobial resistance of H. pylori in Africa. Taking together these data suggest that in several African countries, a clarithromycin-based first-line regimen should be abandoned and the surveillance of antibiotic resistance should lead empirical treatments where an AST is not available.

Figure 1.

Laboratory-based antimicrobial resistance of Helicobacter pylori in Africa. AM: Amoxicillin; CLA: Clarithromycin; FLU: Fluoroquinolones; MET: Metronidazole; RIF: Rifampicin; TET: Tetracycline.

CONCLUSION

H. pylori remains highly prevalent in Africa. However, even in the face of highly pathogenic H. pylori, the clinical manifestations of this infection are still mild. Several factors, which have not been fully studied, fuel this intriguing issue and there is a need for further research to identify host factors that may explain the “African enigma” . The current prevalence of H. pylori in the different African regions does not seemingly provide an accurate view of the prevalence of H. pylori in the continent. It is necessary to carry out studies that will provide population data, and that will use highly accurate methods to correctly detect the presence of H. pylori. However, considering that such research may be expensive in a low resource continent like Africa, meta-analyses grouping data of the different African countries or of the different regions could provide a pooled and better estimate of the prevalence of H. pylori infection. Since H. pylori infection represents a major challenge in Africa, two major issues should be considered, in terms of prevention and cure. First, the possibility of preventing H. pylori acquisition is linked to the availability of a vaccine and to the amelioration of hygienic conditions of the general population[89-91]. However, the fact that H. pylori infection induces strong humoral and cellular immune responses, and that the latter are not able to eliminate the bacterium, raises doubts about the possibility of developing an effective vaccine. Second, in terms of cure, it should be detailed in each country the pattern of H. pylori antibiotic resistance. This is mandatory to establish the more appropriate treatment. Where these data would be available, the epidemiologic surveillance over time should lead clinicians to the choice of the best option.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: No potential conflict of interest and no financial support.

Peer-review started: March 18, 2019

First decision: April 4, 2019

Article in press: June 1, 2019

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Nigeria

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Abadi ATB, Nishida T, Yücel O S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Stella Smith, Department of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, Nigerian Institute of Medical Research, Lagos PMB 2013, Nigeria. stellasmith@nimr.gov.ng.

Muinah Fowora, Department of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, Nigerian Institute of Medical Research, Lagos PMB 2013, Nigeria.

Rinaldo Pellicano, Unit of Gastroenterology, Molinette Hospital, Turin 10126, Italy.

References

- 1.Peek RM, Jr, Crabtree JE. Helicobacter infection and gastric neoplasia. J Pathol. 2006;208:233–248. doi: 10.1002/path.1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pizzorno JE, Murray MT, Joiner-Bey H. Peptic Ulcers. In: The clinicians handbook of Natural Medicine., editor. 3rd ed. St Lois, Missouri: Elsevier; 2016. pp. 779–786. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jonaitis L, Pellicano R, Kupcinskas L. Helicobacter pylori and nonmalignant upper gastrointestinal diseases. Helicobacter. 2018;23 Suppl 1:e12522. doi: 10.1111/hel.12522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.IARC. Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Vol. 61. Lyon: WHO press; 1994. pp. 1–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rugge M, Fassan M, Graham DY. Epidemiology of gastric cancer. In: Strong V, editor. Gastric Cancer. Cham: Springer; 2015. pp. 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graham DY. History of Helicobacter pylori, duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer and gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5191–5204. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i18.5191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pellicano R, Ménard A, Rizzetto M, Mégraud F. Helicobacter species and liver diseases: Association or causation? Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:254–260. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ribaldone DG, Fagoonee S, Hickman I, Altruda F, Saracco GM, Pellicano R. Helicobacter pylori infection and ischemic heart disease: Could experimental data lead to clinical studies? Minerva Cardioangiol. 2016;64:686–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Korwin JD, Ianiro G, Gibiino G, Gasbarrini A. Helicobacter pylori infection and extragastric diseases in 2017. Helicobacter. 2017:22 Suppl 1. doi: 10.1111/hel.12411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain CA, Gisbert JP, Kuipers EJ, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gasbarrini A, Atherton J, Graham DY, Hunt R, Moayyedi P, Rokkas T, Rugge M, Selgrad M, Suerbaum S, Sugano K, El-Omar EM European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group and Consensus panel. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection-the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2017;66:6–30. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hooi JKY, Lai WY, Ng WK, Suen MMY, Underwood FE, Tanyingoh D, Malfertheiner P, Graham DY, Wong VWS, Wu JCY, Chan FKL, Sung JJY, Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Global Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:420–429. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World gastroenterology organisation global guideline: Helicobacter pylori in developing countries. J Dig Dis. 2011;12:319–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2011.00529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zamani M, Ebrahimtabar F, Zamani V, Miller WH, Alizadeh-Navaei R, Shokri-Shirvani J, Derakhshan MH. Systematic review with meta-analysis: The worldwide prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:868–876. doi: 10.1111/apt.14561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanih NF, Dube C, Green E, Mkwetshana N, Clarke AM, Ndip LM, Ndip RN. An African perspective on Helicobacter pylori: Prevalence of human infection, drug resistance, and alternative approaches to treatment. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2009;103:189–204. doi: 10.1179/136485909X398311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walker TD, Karemera M, Ngabonziza F, Kyamanywa P. Helicobacter pylori status and associated gastroscopic diagnoses in a tertiary hospital endoscopy population in Rwanda. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2014;108:305–307. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/tru029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Didelot X, Nell S, Yang I, Woltemate S, van der Merwe S, Suerbaum S. Genomic evolution and transmission of Helicobacter pylori in two South African families. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:13880–13885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304681110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwarz S, Morelli G, Kusecek B, Manica A, Balloux F, Owen RJ, Graham DY, van der Merwe S, Achtman M, Suerbaum S. Horizontal versus familial transmission of Helicobacter pylori. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000180. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nell S, Eibach D, Montano V, Maady A, Nkwescheu A, Siri J, Elamin WF, Falush D, Linz B, Achtman M, Moodley Y, Suerbaum S. Recent acquisition of Helicobacter pylori by Baka pygmies. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003775. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mungazi SG, Chihaka OB, Muguti GI. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in asymptomatic patients at surgical outpatient department: Harare hospitals. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2018;35:153–157. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2018.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanafi NF, Mikhael IL, Younan DN. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Antibodies in Egyptians with Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic purpura and in the General Egyptian Population: A Comparative Study. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2017;6:2482–2492. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bounder G, Boura H, Nadifiyine S, Jouimyi MR, Bensassi M, Kadi M, Eljihad M, Badre, W, Benomar H, Kettani A, Lebrazi H, Maaachi F. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection and related gastric pathologies in Moroccan population. J Life Sci. 2017;11:211–218. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kimang'a AN, Revathi G, Kariuki S, Sayed S, Devani S. Helicobacter pylori: Prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility among Kenyans. S Afr Med J. 2010;100:53–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taddesse G, Habteselassie A, Desta K, Esayas S, Bane A. Association of dyspepsia symptoms and Helicobacter pylori infections in private higher clinic, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2011;49:109–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hestvik E, Tylleskar T, Kaddu-Mulindwa DH, Ndeezi G, Grahnquist L, Olafsdottir E, Tumwine JK. Helicobacter pylori in apparently healthy children aged 0-12 years in urban Kampala, Uganda: A community-based cross sectional survey. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-10-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Archampong TN, Asmah RH, Wiredu EK, Gyasi RK, Nkrumah KN, Rajakumar K. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in dyspeptic Ghanaian patients. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;20:178. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2015.20.178.5024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dube C, Tanih NF, Ndip RN. Helicobacter pylori in water sources: A global environmental health concern. Rev Environ Health. 2009;24:1–14. doi: 10.1515/reveh.2009.24.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dube C, Tanih NF, Clarke AM, Mkwetshana N, Green E, Ndip RN. Helicobacter pylori infection and transmission in Africa: Household hygiene and water sources are plausible factor exacerbating spread- Afr J Biotechnol. 2009;8:6028–6035. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melese A, Genet C, Zeleke B, Andualem T. Helicobacter pylori infections in Ethiopia; prevalence and associated factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19:8. doi: 10.1186/s12876-018-0927-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aje AO, Otegbayo JA, Odaibo GN, Bojuwoye BJ. Comparative study of stool antigen test and serology for Helicobacter pylori among Nigerian dyspeptic patients--a pilot study. Niger J Clin Pract. 2010;13:120–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jemilohun AC, Otegbayo JA, Ola SO, Oluwasola OA, Akere A. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori among Nigerian patients with dyspepsia in Ibadan. Pan Afr Med J. 2010;6:18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Etukudo OM, Ikpeme EE, Ekanem EE. Seroepidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection among children seen in a tertiary hospital in Uyo, southern Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;12:39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ophori EA, Isibor C, Onemu SO, Johnny EJ. Immunological response to Helicobacter pylori among healthy volunteers in Agbor, Nigeria. Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2011;1:38–40. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ishaleku D, Ihiabe, H Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among students of a Nigerian University. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2010;3:584–585. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ezeigbo RO, Ezeigbo CI. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori and its associated peptic ulcer infection among adult residents of Aba, Southeastern, Nigeria. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2016;5:16–21. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith SI, Jolaiya T, Onyekwere C, Fowora M, Ugiagbe R, Agbo I, Cookey C, Lesi O, Ndububa D, Adekanle O, Palamides P, Adeleye I, Njom H, Idowu A, Clarke A, Pellicano R. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among dyspeptic patients with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus in Nigeria. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2019;65:36–41. doi: 10.23736/S1121-421X.18.02528-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Awuku YA, Simpong DL, Alhassan IK, Tuoyire DA, Afaa T, Adu P. Prevalence of helicobacter pylori infection among children living in a rural setting in Sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:360. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4274-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McLaughlin NJ, McLaughlin DI, Lefcort H. The influence of socio-economic factors on Helicobacter pylori infection rates of students in rural Zambia. Cent Afr J Med. 2003;49:38–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bello AK, Umar AB, Borodo MM. Prevalence and risk factors for Helicobacter pylori infection in gastroduodenal diseases in Kano, Nigeria. Afr J Med Health Sci. 2018;17:41–46. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith S, Jolaiya T, Fowora M, Palamides P, Ngoka F, Bamidele M, Lesi O, Onyekwere C, Ugiagbe R, Agbo I, Ndububa D, Adekanle O, Adedeji A, Adeleye I, Harrison U. Clinical and Socio- Demographic Risk Factors for Acquisition of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Nigeria. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2018;19:1851–1857. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.7.1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aguemon BD, Struelens MJ, Massougbodji A, Ouendo EM. Prevalence and risk-factors for Helicobacter pylori infection in urban and rural Beninese populations. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005;11:611–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kouitcheu Mabeku LB, Noundjeu Ngamga ML, Leundji H. Potential risk factors and prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among adult patients with dyspepsia symptoms in Cameroon. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:278. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3146-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.El-Sharouny E, El-Shazli H, Olama Z. Detection of Helicobacter pylori DNA in Some Egyptian Water Systems and Its Incidence of Transmission to Individuals. Iran J Public Health. 2015;44:203–210. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuipers EJ, Meijer GA. Helicobacter pylori gastritis in Africa. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:601–603. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200012060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kidd M, Louw JA, Marks IN. Helicobacter pylori in Africa: Observations on an 'enigma within an enigma'. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;14:851–858. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.1999.01975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Asombang AW, Kelly P. Gastric cancer in Africa: What do we know about incidence and risk factors? Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;106:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holcombe C. Helicobacter pylori: The African enigma. Gut. 1992;33:429–431. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.4.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alaoui Boukhris S, Benajah DA, El Rhazi K, Ibrahimi SA, Nejjari C, Amarti A, Mahmoud M, El Abkari M, Souleimani A, Bennani B. Prevalence and distribution of Helicobacter pylori cagA and vacA genotypes in the Moroccan population with gastric disease. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:1775–1781. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1501-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Al-Eraky DM, Helmy OM, Ragab YM, Abdul-Khalek Z, El-Seidi EA, Ramadan MA. Prevalence of CagA and antimicrobial sensitivity of H. pylori isolates of patients with gastric cancer in Egypt. Infect Agent Cancer. 2018;13:24. doi: 10.1186/s13027-018-0198-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ezzat AHH, Ali MH, El-Seidi, EA, Wali IE, Sedky NA, Naguib SMM. Genotypic characterization of Helicobacter pylori isolates among Egyptian patients with upper gastrointestinal diseases. Chinese-German J Clin Oncol. 2012;11:15–23. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ayana SM, Swai B, Maro VP, Kibiki GS. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopic findings and prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among adult patients with dyspepsia in northern Tanzania. Tanzan J Health Res. 2014;16:16–22. doi: 10.4314/thrb.v16i1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oling M, Odongo J, Kituuka O, Galukande M. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in dyspeptic patients at a tertiary hospital in a low resource setting. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:256. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1184-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alebie G, Kaba D. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and associated factors among gastritis students in Jigjiga University, jigiiga, somali regional state of Ethiopia. J Bacteriol Mycol. 2016;3:234–239. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ankouane F, Noah DN, Enyime FN, Ndjollé CM, Djapa RN, Nonga BN, Njoya O, Ndam EC. Helicobacter pylori and precancerous conditions of the stomach: The frequency of infection in a cross-sectional study of 79 consecutive patients with chronic antral gastritis in Yaoundé, Cameroon. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;20:52. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2015.20.52.5887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ebule IA, Djune FAK, Sitedjeya MIL, Tanni B, Heugueu C, Longdoh AN, Noah ND, Okomo AMC, Paloheimo L, Njoya O, Syrjanen K. Prevalence of H. pylori Infection and Atrophic Gastritis among dyspeptic subjects in Cameroon using a Panel of Serum Biomarkers (PGI, PGII, G-17, HpIgG) Sch J Appl Med Sci. 2017;5:1230–1239. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Afihene MKY, Denyer M, Amuasi JJ, Boakye I, Nkrumah K. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori and endoscopic findings among dyspeptics in Kumasi, Ghana. Open Sci J Clin Med. 2014;2:63–68. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Darko R, Yawson AE, Osei V, Owusu-Ansah J, Aluze-Ele S. Changing Patterns of the Prevalence of Helicobacter Pylori Among Patients at a Corporate Hospital in Ghana. Ghana Med J. 2015;49:147–153. doi: 10.4314/gmj.v49i3.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harrison U, Fowora MA, Seriki AT, Loell E, Mueller S, Ugo-Ijeh M, Onyekwere CA, Lesi OA, Otegbayo JA, Akere A, Ndububa DA, Adekanle O, Anomneze E, Abdulkareem FB, Adeleye IA, Crispin A, Rieder G, Fischer W, Smith SI, Haas R. Helicobacter pylori strains from a Nigerian cohort show divergent antibiotic resistance rates and a uniform pathogenicity profile. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0176454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tanih NF, Okeleye BI, Ndip LM, Clarke AM, Naidoo N, Mkwetshana N, Green E, Ndip RN. Helicobacter pylori prevalence in dyspeptic patients in the Eastern Cape province - race and disease status. S Afr Med J. 2010;100:734–737. doi: 10.7196/samj.4041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ghoshal UC, Chaturvedi R, Correa P. The enigma of Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2010;29:95–100. doi: 10.1007/s12664-010-0024-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seid A, Demsiss W. Feco-prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection among symptomatic patients at Dessie Referral Hospital, Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:260. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3179-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Asrat D, Nilsson I, Mengistu Y, Ashenafi S, Ayenew K, Al-Soud WA, Wadström T, Kassa E. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among adult dyspeptic patients in Ethiopia. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2004;98:181–189. doi: 10.1179/000349804225003190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Loghmari H, Bdioui F, Bouhlel W, Melki W, Hellara O, Ben Chaabane N, Safer L, Zakhama A, Saffar H. Clarithromycin versus metronidazole in first-line Helicobacter pylori eradication. Prospective randomized study of 85 Tunisian adults. Tunis Med. 2012;90:31–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lahbabi M, Alaoui S, El Rhazi K, El Abkari M, Nejjari C, Amarti A, Bennani B, Mahmoud M, Ibrahimi A, Benajah DA. Sequential therapy versus standard triple-drug therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: Result of the HPFEZ randomised study. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2013;37:416–421. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Seddik H, Ahid S, El Adioui T, El Hamdi FZ, Hassar M, Abouqal R, Cherrah Y, Benkirane A. Sequential therapy versus standard triple-drug therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: A prospective randomized study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69:1709–1715. doi: 10.1007/s00228-013-1524-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shehata MA, Talaat R, Soliman S, Elmesseri H, Soliman S, Abd-Elsalam S. Randomized controlled study of a novel triple nitazoxanide (NTZ)-containing therapeutic regimen versus the traditional regimen for eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2017:22. doi: 10.1111/hel.12395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Onyekwere CA, Odiagah JN, Igetei R, Emanuel AO, Ekere F, Smith S. Rabeprazole, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy: report of an efficacy study. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:3615–3619. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i13.3615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sokwala A, Shah MV, Devani S, Yonga G. Helicobacter pylori eradication: A randomised comparative trial of 7-day versus 14-day triple therapy. S Afr Med J. 2012;102:368–371. doi: 10.7196/samj.5302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kabakambira JD, Hategeka C, Page C, Ntirenganya C, Dusabejambo V, Ndoli J, Ngabonziza F, Hale D, Bayingana C, Walker T. Efficacy of Helicobacter pylori eradication regimens in Rwanda: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:134. doi: 10.1186/s12876-018-0863-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sherif M, Mohran Z, Fathy H, Rockabrand DM, Rozmajzl PJ, Frenck RW. Universal high-level primary metronidazole resistance in Helicobacter pylori isolated from children in Egypt. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:4832–4834. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.10.4832-4834.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ramzy I, Elgarem H, Hamza I, Ghaith D, Elbaz T, Elhosary W, Mostafa G, Elzahry MA. Genetic mutations affecting the first line eradication therapy of helicobacter pylori-infected egyptian patients. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2016;58:88. doi: 10.1590/S1678-9946201658088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ben Mansour K, Burucoa C, Zribi M, Masmoudi A, Karoui S, Kallel L, Chouaib S, Matri S, Fekih M, Zarrouk S, Labbene M, Boubaker J, Cheikh I, Hriz MB, Siala N, Ayadi A, Filali A, Mami NB, Najjar T, Maherzi A, Sfar MT, Fendri C. Primary resistance to clarithromycin, metronidazole and amoxicillin of Helicobacter pylori isolated from Tunisian patients with peptic ulcers and gastritis: A prospective multicentre study. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2010;9:22. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-9-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Djennane-Hadibi F, Bachtarzi M, Layaida K, Ali Arous N, Nakmouche M, Saadi B, Tazir M, Ramdani-Bouguessa N, Burucoa C. High-Level Primary Clarithromycin Resistance of Helicobacter pylori in Algiers, Algeria: A Prospective Multicenter Molecular Study. Microb Drug Resist. 2016;22:223–226. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2015.0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bachir M, Allem R, Tifrit A, Medjekane M, Drici AE, Diaf M, Douidi KT. Primary antibiotic resistance and its relationship with cagA and vacA genes in Helicobacter pylori isolates from Algerian patients. Braz J Microbiol. 2018;49:544–551. doi: 10.1016/j.bjm.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Raaf N, Amhis W, Saoula H, Abid A, Nakmouche M, Balamane A, Ali Arous N, Ouar-Korichi M, Vale FF, Bénéjat L, Mégraud F. Prevalence, antibiotic resistance, and MLST typing of Helicobacter pylori in Algiers, Algeria. Helicobacter. 2017:22. doi: 10.1111/hel.12446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bouilhat N, Burucoa C, Benkirane A, El Idrissi-Lamghari A, Al Bouzidi A, El Feydi A, Elouennas M, Benouda A. High-level primary clarithromycin resistance of Helicobacter pylori in Morocco: A prospective multicenter molecular study. Helicobacter. 2015;20:422–423. doi: 10.1111/hel.12219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Seck A, Burucoa C, Dia D, Mbengue M, Onambele M, Raymond J, Breurec S. Primary antibiotic resistance and associated mechanisms in Helicobacter pylori isolates from Senegalese patients. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2013;12:3. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-12-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Seck A, Mbengue M, Gassama-Sow A, Diouf L, Ka MM, Boye CS. Antibiotic susceptibility of Helicobacter pylori isolates in Dakar, Senegal. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2009;3:137–140. doi: 10.3855/jidc.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Aboderin OA, Abdu AR, Odetoyin B', Okeke IN, Lawal OO, Ndububa DA, Agbakwuru AE, Lamikanra A. Antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori from patients in Ile-Ife, South-west, Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2007;7:143–147. doi: 10.5555/afhs.2007.7.3.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Abdulrasheed A, Lawal OO, Abioye-Kuteyi EA, Lamikanra A. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Helicobacter pylori isolates of dyspeptic Nigerian patients. Trop Gastroenterol. 2005;26:85–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Secka O, Berg DE, Antonio M, Corrah T, Tapgun M, Walton R, Thomas V, Galano JJ, Sancho J, Adegbola RA, Thomas JE. Antimicrobial susceptibility and resistance patterns among Helicobacter pylori strains from The Gambia, West Africa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:1231–1237. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00517-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ontsira Ngoyi EN, Atipo Ibara BI, Moyen R, Ahoui Apendi PC, Ibara JR, Obengui O, Ossibi Ibara RB, Nguimbi E, Niama RF, Ouamba JM, Yala F, Abena AA, Vadivelu J, Goh KL, Menard A, Benejat L, Sifre E, Lehours P, Megraud F. Molecular Detection of Helicobacter pylori and its Antimicrobial Resistance in Brazzaville, Congo. Helicobacter. 2015;20:316–320. doi: 10.1111/hel.12204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ndip RN, Malange Takang AE, Ojongokpoko JE, Luma HN, Malongue A, Akoachere JF, Ndip LM, MacMillan M, Weaver LT. Helicobacter pylori isolates recovered from gastric biopsies of patients with gastro-duodenal pathologies in Cameroon: Current status of antibiogram. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13:848–854. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Angol DC, Ocama P, Ayazika Kirabo T, Okeng A, Najjingo I, Bwanga F. Helicobacter pylori from Peptic Ulcer Patients in Uganda Is Highly Resistant to Clarithromycin and Fluoroquinolones: Results of the GenoType HelicoDR Test Directly Applied on Stool. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:5430723. doi: 10.1155/2017/5430723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Asrat D, Kassa E, Mengistu Y, Nilsson I, Wadström T. Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from adult dyspeptic patients in Tikur Anbassa University Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2004;42:79–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lwai-Lume L, Ogutu EO, Amayo EO, Kariuki S. Drug susceptibility pattern of Helicobacter pylori in patients with dyspepsia at the Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi. East Afr Med J. 2005;82:603–608. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v82i12.9364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tanih NF, Okeleye BI, Naidoo N, Clarke AM, Mkwetshana N, Green E, Ndip LM, Ndip RN. Marked susceptibility of South African Helicobacter pylori strains to ciprofloxacin and amoxicillin: Clinical implications. S Afr Med J. 2010;100:49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tanih NF, Ndip RN. Molecular Detection of Antibiotic Resistance in South African Isolates of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:259457. doi: 10.1155/2013/259457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jaka H, Rhee JA, Östlundh L, Smart L, Peck R, Mueller A, Kasang C, Mshana SE. The magnitude of antibiotic resistance to Helicobacter pylori in Africa and identified mutations which confer resistance to antibiotics: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:193. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3099-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ferreira J, Moss SF. Current Paradigm and Future Directions for Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2014;12:373–384. doi: 10.1007/s11938-014-0027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Talebi Bezmin Abadi A. Vaccine against Helicobacter pylori: Inevitable approach. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:3150–3157. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i11.3150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Maleki Kakelar H, Barzegari A, Dehghani J, Hanifian S, Saeedi N, Barar J, Omidi Y. Pathogenicity of Helicobacter pylori in cancer development and impacts of vaccination. Gastric Cancer. 2019;22:23–36. doi: 10.1007/s10120-018-0867-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]