Abstract

Background

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are a class of medications that reduce acid secretion and are used for treating many conditions such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), dyspepsia, reflux esophagitis, peptic ulcer disease, and hypersecretory conditions (e.g. Zollinger‐Ellison syndrome), and as part of the eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori bacteria. However, approximately 25% to 70% of people are prescribed a PPI inappropriately. Chronic PPI use without reassessment contributes to polypharmacy and puts people at risk of experiencing drug interactions and adverse events (e.g. Clostridium difficile infection, pneumonia, hypomagnesaemia, and fractures).

Objectives

To determine the effects (benefits and harms) associated with deprescribing long‐term PPI therapy in adults, compared to chronic daily use (28 days or greater).

Search methods

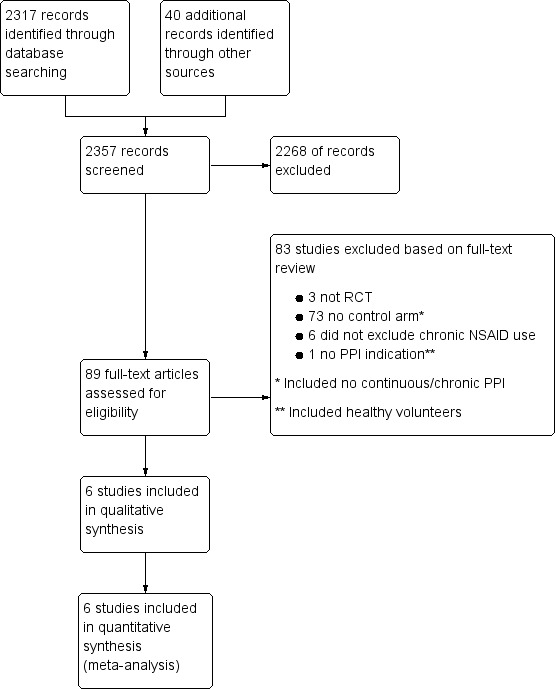

We searched the following databases: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2016, Issue 10), MEDLINE, Embase, clinicaltrials.gov, and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP). The last date of search was November 2016. We handsearched the reference lists of relevant studies. We screened 2357 articles (2317 identified through search strategy, 40 through other resources). Of these articles, we assessed 89 for eligibility.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐randomized trials comparing at least one deprescribing modality (e.g. stopping PPI or reducing PPI) with a control consisting of no change in continuous daily PPI use in adult chronic users. Outcomes of interest were: change in gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, drug burden/PPI use, cost/resource use, negative and positive drug withdrawal events, and participant satisfaction.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently reviewed and extracted data and completed the risk of bias assessment. A third review author independently confirmed risk of bias assessment. We used Review Manager 5 software for data analysis. We contacted study authors if there was missing information.

Main results

The review included six trials (n = 1758). Trial participants were aged 48 to 57 years, except for one trial that had a mean age of 73 years. All participants were from the outpatient setting and had either nonerosive reflux disease or milder grades of esophagitis (LA grade A or B). Five trials investigated on‐demand deprescribing and one trial examined abrupt discontinuation. There was low quality evidence that on‐demand use of PPI may increase risk of 'lack of symptom control' compared with continuous PPI use (risk ratio (RR) 1.71, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.31 to 2.21), thereby favoring continuous PPI use (five trials, n = 1653). There was a clinically significant reduction in 'drug burden', measured as PPI pill use per week with on‐demand therapy (mean difference (MD) ‐3.79, 95% CI ‐4.73 to ‐2.84), favoring deprescribing based on moderate quality evidence (four trials, n = 1152). There was also low quality evidence that on‐demand PPI use may be associated with reduced participant satisfaction compared with continuous PPI use. None of the included studies reported cost/resource use or positive drug withdrawal effects.

Authors' conclusions

In people with mild GERD, on‐demand deprescribing may lead to an increase in GI symptoms (e.g. dyspepsia, regurgitation) and probably a reduction in pill burden. There was a decline in participant satisfaction, although heterogeneity was high. There were insufficient data to make a conclusion regarding long‐term benefits and harms of PPI discontinuation, although two trials (one on‐demand trial and one abrupt discontinuation trial) reported endoscopic findings in their intervention groups at study end.

Plain language summary

Stopping or reducing versus continuing long‐term proton pump inhibitor use in adults

Review question

This review aimed to build on prior work and evaluate the effects of stopping or lowering the dose of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs; acid‐reducing medicines) in adults, compared to what is commonly done in practice (i.e. continuing long‐term (more than four weeks) daily PPI use. Effects include both benefits and harms (e.g. pill use, symptom control, and cost).

Background

PPIs are used for many different conditions (e.g. heartburn, acid reflux, stomach ulceration). Studies for most of these conditions only support short‐term use (two to 12 weeks), yet these medicines are commonly continued for prolonged periods or even indefinitely. Long‐term PPI use contributes to medicine misuse and puts people at risk of experiencing unwanted drug interactions and side effects (e.g. diarrhea, headache, bone fractures). It also leads to a high cost burden on the healthcare system. 'Deprescribing' involves slowly withdrawing and stopping medicines. The most common approach is 'on‐demand' therapy, which allows people to use medicines only when they have symptoms (i.e. when heartburn begins). The overall goal of deprescribing is to minimize the number of medicines a person takes, thereby reducing inappropriate medicine use and avoiding side effects.

Study characteristics

We found six trials with 1758 participants. Of these, five studies looked at on‐demand deprescribing and one trial looked at abruptly stopping PPIs. Participants were aged 48 to 57 years, except for one trial (average age of 73 years). The majority of participants had moderate heart burn and acid reflux with milder forms of esophagitis (inflammation of the food pipe that may lead to damage).

Key results

We found that deprescribing methods led to worse symptoms control while considerably reducing pill use. Deprescribing PPIs may lead to side effects such as inflammation of the esophagus. Very few data were available to make a conclusion regarding long‐term benefits and harms of PPI reduction or discontinuation.

Quality of the evidence

Overall, the quality of evidence for this review ranged from very low to moderate. Trials were inconsistent with how they reported symptom control. There were also limitations in how the studies were conducted (e.g. participants and investigators may have known which medicine they received), which lowered the quality of evidence. Other contributing factors included small sample sizes for most trials and inconsistent results between studies.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. On‐demand deprescribing compared to continued use for people with moderate GERD and mild esophagitis.

| On‐demand deprescribing compared to continued use for people with moderate GERD and mild esophagitis | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with moderate GERD and mild esophagitis, mean age 48 to 57 years Settings: outpatient Intervention: on‐demand deprescribing Comparison: continued use | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Continued use | On‐demand deprescribing | |||||

| Lack of symptom control | Study population | RR 1.71 (1.31 to 2.21) | 1653 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1,2 | ‐ | |

| 92 per 1000 | 157 per 1000 (120 to 203) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 123 per 1000 | 210 per 1000 (161 to 272) | |||||

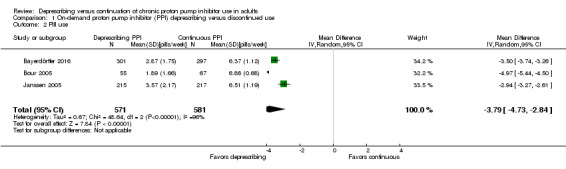

| Pill use (pills/week) | ‐ | The mean pill use (pills/week) in the intervention groups was 3.79 lower (4.73 to 2.84 lower) | ‐ | 1152 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate3 | ‐ |

| Cost/resource use | We found no data on cost or resource use. | Not estimable | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

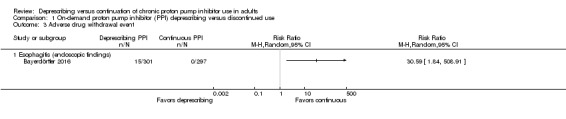

| Adverse drug withdrawal events ‐ esophagitis (endoscopic findings) | ‐ | ‐ |

RR 30.59 (1.84 to 508.91) |

598 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1,2 |

Risk not estimable as no events in continued use arm. |

| Participant satisfaction | Study population | RR 1.82 (1.26 to 2.65) | 1653 (5 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low2,4,5 | ‐ | |

| 88 per 1000 | 160 per 1000 (111 to 234) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 81 per 1000 | 147 per 1000 (102 to 215) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level due to a high risk of detection bias, and attrition bias. 2 Downgraded one level due to wide confidence intervals and summary statistic close to the line of no effect. 3 Downgraded one level due to high risk of detection and attrition bias. 4 Downgraded one level due to high risk of attrition and reporting bias. 5 Downgraded one level due to indirectness as poor methods of satisfaction used (willingness to continue or "inadequate relief").

Summary of findings 2. Abrupt discontinuation deprescribing compared to continued use for people with mild‐to‐moderate esophagitis.

| Abrupt discontinuation deprescribing compared to continued use for people with mild to moderate esophagitis | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with mild to moderate esophagitis, symptomatic, aged > 18 years (mean age 73 years) Settings: outpatient Intervention: abrupt discontinuation deprescribing Comparison: continued use | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Continued use | Abrupt discontinuation deprescribing | |||||

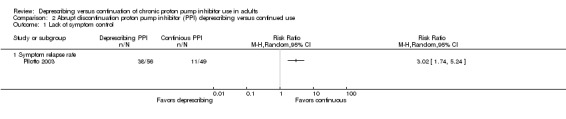

| Lack of symptom control | Study population | RR 3.02 (1.74 to 5.24) | 105 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low1,2 | ‐ | |

| 224 per 1000 | 678 per 1000 (391 to 1000) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 225 per 1000 | 679 per 1000 (392 to 1000) | |||||

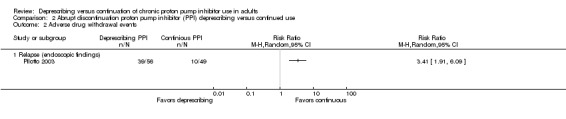

| Adverse drug withdrawal events ‐ relapse (endoscopic findings) | Study population | RR 3.41 (1.91 to 6.09) | 105 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low1,2 | ‐ | |

| 204 per 1000 | 696 per 1000 (390 to 1000) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 204 per 1000 | 696 per 1000 (390 to 1000) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level due to concerns surrounding attrition bias and blinding. 2 Downgraded two levels due to wide confidence intervals, and small number of participants and events.

Background

See Appendix 1 for a glossary of terms and Appendix 2 for abbreviations used in this review.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are a class of medications that reduce acid secretion by inhibiting gastric H+, K+‐adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase). They are used for treating many conditions such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), dyspepsia (i.e. indigestion), reflux esophagitis (inflammation of the esophagus), peptic ulcer disease (PUD), hypersecretory conditions (e.g. Zollinger‐Ellison syndrome), and as part of the eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) bacteria (Wallace 2011). They are also used to prevent and reduce the risk of ulcers in people with a history of PUD, in critically ill people as stress ulcer prophylaxis (SUP), and people who use chronic nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (Armstrong 1999; Armstrong 2005).

Description of the condition

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

GERD affects millions of adults globally. Approximately five million Canadians experience heartburn or regurgitation (or both) at least once weekly, where heartburn is the most common symptom reported (17%) followed by regurgitation (11%) (CDHF 2015; Tougas 1999). Similar figures also extend globally. One systematic review evaluating the epidemiology of GERD found that 10% to 20% of adults in Western countries are also affected by GERD (Dent 2005).

Many GERD publications and guidelines exist though a uniform definition of GERD among them is lacking. The Canadian Consensus on the Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Adults (Canadian Consensus) defines GERD as the "reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus causing (a) symptoms sufficient to reduce quality of life, and/or (b) esophageal injury". The hallmark symptoms are heartburn and acid regurgitation. The Canadian Consensus also classifies GERD as either 'mild' or 'moderate and severe' disease (Armstrong 2005). The American College of Gastroenterology's (ACG) Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease recognizes that GERD is "defined by consensus and as such is a disease comprising symptoms, end‐organ effects and complications related to the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus, oral cavity and/or the lung" (Katz 2013). The ACG categorizes GERD based on endoscopic findings: nonerosive GERD (NERD) is symptomatic GERD with negative endoscopy, while GERD with erosive findings on endoscopy is referred to as erosive reflux disease or erosive esophagitis (EE) (Katz 2013). In 2006, the Global Consensus Group published the Montreal Definition and Classification of GERD to determine a globally acceptable definition that would be useful for patients, practitioners, and health agencies. This group defined GERD as, "a condition which develops when the reflux of stomach contents cause troublesome symptoms and/or complications", such as heartburn, regurgitation, and esophageal injury (i.e. reflux esophagitis) (Vakil 2006).

Reflux esophagitis

PPIs are also commonly used on a long‐term basis for esophagitis due to chronic GERD. The severity of EE detected on endoscopy is classified by the Los Angeles (LA) Grading criteria as grades A to D, defined as follows: grade A ‐ at least one mucosal break of 5 mm or less, not extending between the tops of two mucosal folds; grade B ‐ at least one mucosal break with a length greater than 5 mm not extending between the tops of two mucosal folds; grade C ‐ at least one mucosal break involving less than 75% of the esophageal circumference, but extending between the tops of at least two mucosal folds; grade D ‐ at least one mucosal break involving 75% or more of the esophageal circumference (Lundell 1999). LA Grade C and D esophagitis are considered severe stages of esophagitis, have lower rates of healing with PPIs, and are more prone to relapse in the absence of maintenance therapy (Katz 2013). The Canadian Dyspepsia Working Group suggest that healing and symptom relief of EE is superior with PPIs as compared to histamine H2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs), and that standard doses of PPIs are superior to half or low doses of PPIs for this indication (Veldhuyzen van Zanten 2005). Barrett's esophagus is another long‐term sequelae of GERD and esophagitis that is believed to be developed from the change of normal esophageal epithelial cells to specialized intestinal glandular epithelial cells. This metaplasia, detectable via endoscopy, can progress to dysplasia, and finally adenocarcinoma (Armstrong 2005). The ACG guidelines recommend ongoing maintenance PPI therapy for people with EE and Barrett's esophagus (Katz 2013). Since Barrett's esophagus is believed to result from chronic acid reflux, the Canadian guidelines suggest that regardless of symptoms, it should be treated with lifelong PPIs of at least standard dose, and managed by specialists (Veldhuyzen van Zanten 2005).

Peptic ulcer disease

Gastric and duodenal ulcers (bleeding or nonbleeding) are often referred to under the rubric of PUD (ACPG 2000; Katz 2013; Talley 2005). There are many risk factors and possible causes for PUD, the most common being infection of the gastric mucosa with H. pylori; however, other causes include NSAID‐ or drug‐induced PUD, and hypersecretory states. The standard for H. pylori‐positive PUD is treatment with triple therapy (two antibiotics and one PPI) to eradicate the bacteria. This is typically followed by four to eight weeks of PPI therapy for gastric ulcers, but does not require subsequent PPI therapy in the setting of uncomplicated duodenal ulcers. If eradication is achieved, the rate of rebleeding is very low (1.3% over 11 to 53 months) (Gisbert 2004; Laine 2012; Malfertheiner 2009).

NSAIDs, and to a lesser extent newer selective cyclooxygenase‐2 (COX2) inhibitors, are known to cause dyspeptic symptoms and increase the risk of PUD through the inhibition of cyclooxygenase‐1 (COX1) enzyme in the gastric mucosa. There is support for the concomitant use of gastroprotective agents (PPIs, misoprostol, or H2RAs) as primary or secondary prophylaxis of peptic ulcers, especially in the presence of risk factors. These include age 65 years or over; history of bleeding PUD; and use of corticosteroids, anticoagulants, or antiplatelet agents (Veldhuyzen van Zanten 2005). If people are to be maintained on long‐term NSAID therapy, it is advised to test and treat for H. pylori due to the additive risk (Veldhuyzen van Zanten 2005).

Description of the intervention

'Deprescribing' involves slowly withdrawing and stopping medications, with the aim of reducing polypharmacy and inappropriate medication use thereby improving people's outcomes (Thompson 2013). A number of approaches to deprescribing have been outlined by the Canadian Consensus: intermittent PPI use is defined as a "daily intake of a medication for a predetermined, finite period (usually two to eight weeks) to produce resolution of reflux‐related symptoms or healing of esophageal lesions following relapse of the individual's condition"; on‐demand PPI use is defined as "the daily intake of a medication for a period sufficient to achieve resolution of the individual's reflux‐related symptoms; following symptom resolution, the medication is discontinued until the individual's symptoms recur, at which point, medication is again taken daily until the symptoms resolve" (Armstrong 2005). Other deprescribing methods may include stopping therapy abruptly or via a tapering regimen, switching to an alternate therapy (e.g. stepping down from PPI to H2RA), lowering the total daily dose, or, in the case of active H. pylori infection, treating the infection and then discontinuing PPI therapy.

Small studies have demonstrated successful deprescribing approaches, yet currently no systematically developed guidelines exist that describe known benefits and harms of deprescribing (Gnjidic 2012; Iyer 2008). Furthermore, there are no evidence‐based methods of stopping (i.e. tapering and monitoring) specific drugs to help guide prescribers and other clinicians.

The concept of deprescribing is straightforward, yet many barriers exist for clinicians and patients (Raghunath 2005; Reeve 2012; Reeve 2013). Barriers include: clinician internal pressures (i.e. believing drug therapy is effective, safe, and recommended, and desire to prescribe it), clinician workload pressures (i.e. desire to avoid repeat consultations), patient pressures (i.e. people requesting therapy or unwilling to stop an effective treatment or switch to an alternative), and marketing and commercial influences. Additionally, clinicians and patients may disagree with the appropriateness of deprescribing, possibly related to belief of lack of suitable alternatives, fear of return or worsening of a person's symptoms, and influences of negative past experiences or experiences of others. Clinicians also believe that patients may be unwilling to discontinue PPIs as it allows for continued adverse lifestyle habits that contribute to GERD symptoms (e.g. smoking or poor diet), although this has not been confirmed by existing literature (Grime 2001). Clinicians may also be reluctant to discontinue medications initiated by other health professionals. The lack of guidelines and fear/concern of withdrawal or rebound symptoms are key concerns limiting the implementation of deprescribing initiatives. In addition, polypharmacy often is not addressed, with adverse drug effects being mistaken for new conditions requiring additional treatment, thus driving the cycle of inappropriate prescribing (Anthierens 2010; Hilmer 2009).

How the intervention might work

Various deprescribing methods exist. While the underlying goal of deprescribing is the same (i.e. to stop or reduce in an attempt to discontinue or achieve the lowest effective dose), the methods and outcomes may differ. Different methods for reducing drug exposure have been reported (e.g. pharmacist‐led medication reviews, prescriber feedback, and multidisciplinary interventions), though their resulting clinical outcomes are not always reported (Gnjidic 2012). Such outcomes include positive drug withdrawal events (PDWE) and adverse drug withdrawal events (ADWE). Graves and colleagues defined ADWE as a "clinically significant set of signs or symptoms caused by the removal of a drug" (Graves 1997). Indeed, ADWEs are major contributors to unsuccessful deprescribing. In contrast, desirable outcomes (i.e. reduction/elimination of potential or actual drug‐related adverse events) may result from drug withdrawals, which will be referred to in this review as PDWEs. Successful deprescribing may also result in reduced drug interactions, increased quality of life and patient satisfaction, as well as reduced drug burden and costs.

Stopping PPIs by abrupt withdrawal or by slowly withdrawing or reducing the dose has been theorized to have beneficial effects, as well as potential harms. As suggested by Linsky and colleagues, PPIs are often viewed as having few adverse effects; however, their long‐term use has been associated with an increased risk of pneumonia, Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) colitis, and osteoporotic fractures (Linsky 2013). Limiting PPI doses or stopping PPIs via one of the three interventions that will be assessed in this review may reduce the risk of such adverse events.

One Cochrane review by Donnellan and colleagues investigated comparative efficacies of various therapies (including PPIs) in preventing relapse in people with esophagitis and endoscopy‐negative reflux disease (Donnellan 2004). The current review adds to the knowledge established by Donnellan 2004, by including additional indications for PPI use, and focusing on trials that allow for comparison of different maintenance therapy strategies with a control of no change in continuous PPI use.

One systematic review by Lee and colleagues evaluated whether people with GERD were receiving unnecessary maintenance PPI therapy or high‐dose PPI therapy (Lee 2004). The review included deprescribing trials, including randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and nonrandomized trials, of switching to H2RA, intermittent or on‐demand PPI use, and dose reduction of high‐dose PPIs. The review reported that 80% of people receiving high‐dose PPIs were able to reduce their doses successfully to standard‐dose PPIs. Based on results of participant symptom assessments, deprescribing was possible in 26% to 71% of people with GERD (Lee 2004). Despite these results, it remains unclear how the deprescribing interventions evaluated by Lee and colleagues compare to people who would continue on long‐term PPI therapy (e.g. without a change in dose), and which benefits or risks exist with deprescribing.

Jiang 2013 undertook another systematic review and meta‐analysis of on‐demand PPI. This group measured the proportion of people who were unwilling to continue on‐demand therapy compared to people unwilling to continue on daily PPI therapy or placebo. They found that on‐demand therapy reduced the risk of being unwilling to continue compared to daily PPI therapy and placebo. This meta‐analysis did not report on other outcomes such as pill burden, ADWEs, or symptom relapse and may not have included all studies relevant for our review. Further, most people in practice will continue on the same dose of PPI long‐term. Studies in the Jiang 2013 meta‐analysis did not compare people with on‐demand PPI use to people who continued on the same dose of PPI long‐term with no change in regimen. As such, the effect of on‐demand use compared to continued PPI use is not well‐established.

The present systematic review builds on prior work and evaluates evidence of deprescribing compared to what is commonly done in practice, that is, continuing chronic PPI use with no change in regimen.

Why it is important to do this review

The evidence for PPI use in many indications (e.g. GERD, PUD, SUP) only supports short‐term use (e.g. two to 12 weeks), yet these drugs are commonly continued for prolonged periods or even indefinitely, without appropriate reassessment (Donnellan 2004; Reimer 2009a).

Continuous use of PPIs for durations exceeding accepted standards appears to be commonplace, and is likely because they are very well tolerated and considered benign compared to other prescribed medications. This relatively desirable safety profile often overshadows lesser known drug interactions (e.g. hepatic enzyme inhibition, effects on drug absorption or activation) and poorly understood adverse effects and associated risks (vitamin B12 deficiency, hypomagnesemia, community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP), C. difficile infection, diarrhea, headache, and fractures) (Ament 2012; Chubineh 2012; Fohl 2011; Linsky 2013). Although these adverse effects may not be very common and true association with risk is debatable, the extensive use of PPIs in a wide range of populations without monitoring and reassessment is concerning.

The Canadian Health Network reported that six PPIs were in the top 100 prescribed drugs in 2012, with pantoprazole ranking fifth at 11,051,000 prescriptions dispensed in Canadian retail pharmacies over a 12‐month period (CHN 2013). Due to this widespread and chronic use, even rare adverse events will present over time and put people at risk.

Inappropriate PPI use is not only commonplace in Canada, it is also a major global issue. It is estimated that between 20% and 82% of people worldwide are using a PPI without an indication (Claudene 2008; Dangler 2013; Heidelbaugh 2010; Leri 2013; Molloy 2010; Reeve 2015; Wahab 2012). For example, in one cross‐sectional study of people in primary care in Denmark receiving long‐term PPI therapy, 39% had never undergone a trial withdrawal, and only 27% had a verified diagnosis indicating the need for PPI therapy (Reimer 2009a). These findings also parallel those of one Australian study (Gadzhanova 2012). The Gastroenterological Society of Australia (GESA) make specific recommendations to consider 'stepdown' therapy, cessation, or dose reduction, in targeted populations (e.g. milder grades of esophagitis or mild reflux symptoms) (GESA 2011), yet, Gadzhanova 2012 found that only one‐third of people initiated on high‐dose PPIs were stepped down, as per GESA recommendations.

Another example of inappropriate PPI therapy includes continuation of SUP after discharge from various intensive care unit (ICU) settings in the US (Heidelbaugh 2010). Guidelines suggest use of SUP (PPI or H2RA) in critically ill people with coagulopathy, mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours, or a history of gastrointestinal (GI) ulceration or bleed within the last year (Armstrong 1999; Spirt 2006). However, many people continue SUP therapy after discharge when it is no longer indicated. Murphy and colleagues published a study demonstrating this in people in surgical ICUs (Murphy 2008). The authors concluded that PPIs and H2RAs were continued in 24.2% of people upon discharge from hospital.

Leri and colleagues also described PPI misuse. The authors conducted a retrospective review to identify PPI continuation at discharge in people who had a PPI initiated in hospital. The authors reported 78% to 82% of people were discharged on a PPI inappropriately between 2005 and 2008 (Leri 2013).

The overuse of PPIs has also led to tremendous costs. The Canadian Health Network report listed eight brands of PPIs in the top 100 products based on prescription cost (CHN 2013). Esomeprazole (Nexium) ranked at seven with a cost of CAD 257,173,000 for the cited 12‐month period (CHN 2013). In one 2007 Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) report on economics surrounding treatment of dyspepsia and GERD compared five treatment regimens: on‐demand H2RA, on‐demand PPI, maintenance H2RA, maintenance PPI, and PPI with stepdown to H2RA (CADTH 2007). In the setting of EE and investigated GERD, on‐demand PPI therapy had the lowest expected one‐year costs (CAD 537/year for EE and CAD 635/year for GERD) compared with maintenance PPI treatment, which had the highest estimated cost (CAD 776/year for EE and CAD 816/year for GERD; estimates based on 2006 Ontario costs). In the NERD population, the most cost‐effective strategy was on‐demand H2RA (CAD 641/year) and the most costly strategy remained maintenance PPI therapy (CAD 827/year). In terms of efficacy, the report documented "expected weeks with heartburn" for each therapy. In all three populations, maintenance PPI therapy resulted in the lowest number of weeks with heartburn, followed second in all instances by PPI with stepdown to H2RA. The least effective treatment in all populations was on‐demand H2RA.

Several western countries have also reported high expenditure on PPIs. In 2006, GBP 425 million was spent on PPIs in England, and the same issue extends globally to GBP 7 billion (Forgacs 2008).

Inappropriate use of PPIs can contribute to polypharmacy, which is the use of multiple medications, specifically those that are not indicated. Polypharmacy may result in reduced medication adherence, falls, cognitive impairment, functional impairment, delirium, and hospitalization, all of which increase morbidity and mortality (Gnjidic 2012; Hilmer 2009; Iyer 2008). The notion of deprescribing is becoming more relevant as clinicians begin to acknowledge the risks associated with polypharmacy (Scott 2013).

Objectives

To determine the effects (benefits and harms) associated with deprescribing long‐term PPI therapy in adults, compared to chronic daily use (28 days or greater).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included RCTs and quasi‐randomized trials. We applied no limitation on language or abstracts.

Types of participants

Participants were adults (aged 18 years or greater) using a PPI chronically for one month (28 days) or greater. Participants also required an indication for PPI use: GERD (nonerosive reflux disease or GERD LA Grade A to D), functional dyspepsia, or undiagnosed dyspepsia. Participants were also considered eligible if they had a history PUD (bleeding or nonbleeding, or both), H. pylori‐positive or ‐negative diagnoses, recurrent peptic esophageal stricture or Barrett's esophagitis. Participants using a PPI as SUP or for gastroprotection in the setting of low‐dose acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) (less than 325 mg/day), anti‐inflammatory doses of NSAIDs, and steroids were eligible. We excluded trials if participants were taking high‐dose NSAIDs who require chronic PPI use for gastroprotection; however, those with occasional NSAID use were not excluded.

Types of interventions

Included studies compared at least one of the deprescribing modalities with a control consisting of no change in continuous daily PPI use. Deprescribing was defined as one or more of the following interventions:

Stopping PPI therapy: either via abrupt discontinuation or a tapering regimen.

Step down: following abrupt discontinuation or tapering of PPI, an H2RA was prescribed (any H2RA at any approved dose and dosing interval per drug monograph).

-

Reduction in PPI, which included the following subcategories:

intermittent PPI use as previously defined by the Canadian Consensus (Armstrong 2005);

on‐demand PPI use as previously defined by the Canadian Consensus (Armstrong 2005);

lower dose: continuous daily PPI therapy at a lower dose compared to a control arm within the trial.

Treatment of H. pylori (using any approved triple or quadruple therapy) followed by four to eight weeks of PPI maintenance therapy for bleeding or nonbleeding PUD and then PPI discontinuation.

We excluded studies if treatment arms consisted of concomitant interventions such as rescue therapy (e.g. with antacids), lifestyle, diet modifications, or a combination of these. This did not affect inclusion if these additional interventions were handled similarly in all treatment arms.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Lack of symptom control: reported as harms due to no change, recurring, worsening, new onset of at least one upper GI symptom (heartburn, regurgitation, dyspepsia, epigastric pain, nausea, bloating, belching).

Drug burden/PPI use.

Cost/resource use.

Secondary outcomes

PDWE: included any positive outcome (e.g. improvement in cognition, improvement in vitamin B12 levels, resolution of diarrhea) experienced as a result of the deprescribing intervention.

ADWE: included all negative outcomes or adverse effects (e.g. GI bleeding, worsening endoscopic findings) occurring as a result of deprescribing with the exception of GI symptoms, which were measured separately.

Participant satisfaction: positive or negative.

Search methods for identification of studies

We placed no restrictions on the language of publication.

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2016, Issue 10) (Appendix 3);

MEDLINE (1946 to 15 November 2016) (Appendix 4);

Embase (1980 to 15 November 2016) (Appendix 5);

ClinicalTrials.gov;

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP).

As deprescribing is a new concept in the literature, we used a broad range of key words. Search terms for PPIs included both the generic and common brand names (Donnellan 2004; Van Herwaarden 2014). A librarian from Cochrane reviewed the search strategy and a research librarian completed the search strategy (see Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5). Review authors will conduct future literature searches.

Searching other resources

We handsearched reference lists of all primary studies and review articles.

Data collection and analysis

We used predefined data extraction fields and data collection forms. We used Review Manager 5 for data analysis (RevMan 2014). For RCTs with dichotomous outcomes, we collected the number of outcome events and the total number of participants in treatment and control groups.

Selection of studies

Three review authors (FJR, TB, and WT) independently reviewed search results, assessed study eligibility and trial quality, and extracted data. We resolved disagreements by discussion with another review author (CRF). The review authors retrieved and independently screened full‐text study reports and publications and identified studies for inclusion and identified/recorded reasons for exclusion of the ineligible studies. We made every attempt to exclude duplicates. We constructed a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) and a Characteristics of excluded studies table based on the information collected during this process. We used a standardized eligibility checklist.

1.

Study flow diagram. NSAID: nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug; PPI: proton pump inhibitor; RCT: randomized controlled trial.

Data extraction and management

We used a standard data collection form for study characteristics and outcome data. Prior to data collection, two review authors independently completed a pilot eligibility and data extraction exercise to ensure criteria were consistently applied (Higgins 2011). Three review authors (FJR, TB, and WT) extracted the following study characteristics from included studies:

methods: study design, total duration study and run in, number of study centers and location, study setting, withdrawals, date of study;

participants: number, mean age, age range, gender, severity of condition, types of condition, inclusion criteria, and exclusion criteria;

interventions: intervention, comparison, concomitant medications;

outcomes: primary and secondary outcomes, time points reported;

other: author contact information, funding for trial, notable conflicts of interest of trial authors.

We resolved disagreements by discussion with a third review author (CRF). One review author (FJR) transferred the data into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014). A second author (TB) reviewed data entry for accuracy.

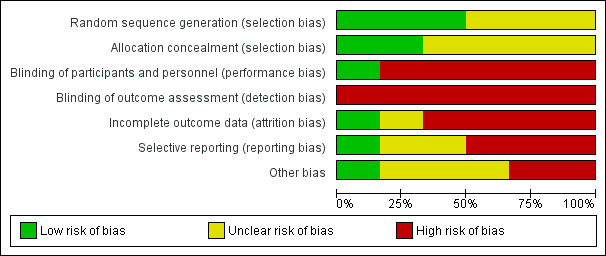

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the quality and strength of the evidence using GRADE and study bias using Cochrane's tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011).

Three review authors (FJR, TB, and WT) independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved disagreements by discussion with a third review author (CRF). We ranked each potential source of bias as high, low, or unclear and provided a quote from the study to justify the bias grade (refer to Characteristics of included studies table for risk of bias assessments) using the following domains:

random sequence generation;

allocation concealment;

blinding of participants and personnel;

blinding of outcome assessment;

incomplete outcome data;

selective outcome reporting;

other bias.

Assessment of bias in conducting the systematic review

The review was conducted according to the published protocol and any deviation from the protocol is reported in the Differences between protocol and review section.

Measures of treatment effect

We reported results as risk ratios (RR) where possible with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We pooled dichotomous data using a random‐effects model (Dersimonian 1986), and continuous outcomes using mean differences (MD) when outcomes were measured on the same scale.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the individual participant undergoing PPI treatment. We conducted a scoping exercise prior to commencing the review and did not identify any cluster‐randomized trials for this comparison. As expected, we found no cluster‐randomized trials for this comparison after conducting comprehensive literature searching during the review.

Dealing with missing data

During the data extraction process, we attempted to contact the primary author for clarification regarding missing or unclear data. No data were imputed.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used the Chi2 statistic and I2 statistic to measure heterogeneity among the trials in each analysis. If we identified substantial heterogeneity (Chi2 statistic with a P value less than 0.15 or I2 statistic greater than 25%) via either statistic, we planned to explore this through prespecified subgroup analysis. Due to the paucity of included trials, we did not perform predefined subgroup analyses to investigate causes of heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We used the methods outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions for assessment of bias (Higgins 2011). We attempted to contact study authors to request missing outcome data. Refer to Characteristics of included studies table for risk of bias assessment.

Data synthesis

We used Review Manager 5 for analysis (RevMan 2014). We calculated 95% CIs for the treatment effect and used the Mantel‐Haenszel method for dichotomous data and the inverse variance method for continuous data. We used a random‐effects models for the analysis (DerSimonian 1986).

'Summary of findings' table

We created 'Summary of findings' tables based on the type of intervention (Table 1; Table 2). We used the five GRADE considerations to assess the quality of evidence using methods and recommendations described in Section 8.5 and Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) and GRADEpro software (GRADEpro). We justified all decisions to downgrade or upgrade the quality of studies by using footnotes, and we made comments to aid the reader's understanding of the review. We considered whether any additional outcome information was provided that we were unable to incorporate into meta‐analyses, and we planned to note this in the comments and state whether it supported or contradicted information derived from the meta‐analyses.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to carry out the following subgroup analyses.

Deprescribing interventions (stopping PPI, lower‐dose PPI compared to control arm, on‐demand PPI, intermittent PPI, stopping PPI and changing to H2RA, treatment of H. pylori with four to eight weeks of PPI therapy).

Diagnosis (GERD, esophagitis, functional dyspepsia, PUD, H. pylori infection).

Trial setting (primary versus secondary care).

Age (young adults versus older adults).

We planned to assess the robustness of the conclusions based on the risk of bias assessments for blinding and allocation. We were unable to conduct subgroup analysis given the limited data.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analysis defined a priori to assess the robustness of our conclusions by: outcome reporting and participant populations, and to assess any effect of risk of bias on our estimates. Data were too limited to perform sensitivity analysis.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies tables for details.

Results of the search

We identified 2357 references; 2317 through electronic searches of CENTRAL (Wiley), MEDLINE (OvidSP), and Embase (OvidSP), and 40 through other resources. We excluded 2268 clearly irrelevant references by reading the abstracts and retrieved 89 references for further detailed assessment. We excluded 83 references for the reasons listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Six references fulfilled the inclusion criteria (Characteristics of included studies table). The results of the search are presented in Figure 1.

Included studies

We included six RCTs with 1753 participants (Bayerdörffer 2016; Bour 2005; Janssen 2005; Morgan 2007; Pilotto 2003; Van der Velden 2010). The Characteristics of included studies table outlines details (e.g. sample size, participant characteristics, interventions, etc.) of all studies that met inclusion criteria.

Design

All six trials were RCTs. Four studies had an open‐label design while two were double‐blinded. To satisfy the inclusion criteria of chronic PPI usage (28 days or greater) with a control arm of no change in continuous daily PPI use, trials were required to have a run‐in phase of at least four weeks prior to randomization. For all trials, participants required symptom resolution at the end of the run‐in phase, prior to randomization. One trial went further and evaluated participants endoscopically at the beginning and end of the trial to assess the development of esophagitis (Bayerdörffer 2016). Five trials explored on‐demand therapy and one trial investigated abrupt discontinuation (Pilotto 2003). Five studies had a duration of six months, while Van der Velden 2010 conducted a trial of 13 weeks.

Sample size

The included trials were relatively small (fewer than 500). A significant number of participants were excluded after the run‐in phases, as they did not achieve symptom resolution. Pilotto 2003 included the fewest participants after the run‐in phases (n = 105) and Bayerdörffer 2016 had the largest trial (n = 598).

Setting

Morgan 2007 included participants from 23 Canadian sites. Pilotto 2003 had participants from 16 Italian centers. Van der Velden 2010 included participants from 23 general practices from central and eastern regions of the Netherlands. The trial by Bour 2005 included 41 French hospital sites (exact locations not disclosed). Janssen 2005 included participants from 58 centers (29 in Germany, 12 in France, 11 in Switzerland, and six in Hungary). Bayerdörffer 2016 included people from 61 sites (Austria, France, Germany, South Africa, and Spain).

Participants

All participants were from the outpatient setting and had either NERD or milder grades of esophagitis (LA grade A or B). Participants also varied in age. one trial only included participants aged 65 years or greater (mean age 73 years) (Pilotto 2003), while the remaining trials included relatively younger participants (mean age 48 to 57 years). Four trials reported risk factors of alcohol and tobacco use (Bour 2005; Morgan 2007; Pilotto 2003; Van der Velden 2010), and three trials indicated that heartburn was the major symptom experienced (Bayerdörffer 2016; Bour 2005; Morgan 2007).

Interventions

Pilotto 2003 examined abrupt discontinuation and the remaining trials investigated on‐demand deprescribing. Three trials used pantoprazole 20 mg pills, two used rabeprazole 10 mg and 20 mg pills, and one used esomeprazole 20 mg pills. Duration of treatment was similar for five trials (six months or up to six months), while the remaining trial was conducted over 13 weeks (Van der Velden 2010).

Outcomes

Five studies defined primary outcomes; Bayerdörffer 2016; Bour 2005; Janssen 2005; and Morgan 2007 pertained to symptom control and relief and Van der Velden 2010 reported volume of rescue medications as their primary outcome and symptom control, quality of life and final dose adjustment as secondary outcomes. Pilotto 2003 did not define primary outcomes.

Excluded studies

We excluded 83 studies. Three studies had the wrong study design (i.e. not RCTs) (Bautista 2006; Inadomi 2001; Ponce 2004). Six studies included chronic NSAID users (Annibale 1998; Bate 1997; Dent 1994; Gough 1996; Hatlebakk 1997a; Hatlebakk 1997b). In one study, participants did not have an indication for PPI use (i.e. healthy volunteers) (Niklasson 2010). Seventy‐three studies did not have a control arm (i.e. no continuous/no change in chronic PPI use) (Archambault 1988; Bardhan 1990; Bardhan 1995; Bate 1989; Bate 1990; Bate 1995; Bayerdörffer 1993; Bigard 2005; Björnsson 2006; Bytzer 2004; Carlsson 1998; Chen 1993; Dabholkar 2011; Deboever 2003; Dent 1989; DeVault 2006; Earnest 1998; Eggleston 2009; Escourrou 1999; Farley 2000; Fass 2011; Fass 2012; Fennerty 2009; Goh 1995; Goh 2007; Havelund 1988; Hoshino 1995; Howden 2001; Howden 2009; Hsu 2015; Inadomi 2003; James 1994; Johnson 2001; Johnson 2010; Jones 1997; Juul‐Hansen 2008; Kaplan‐Machlis 2000; Kaspari 2005; Klinkenberg‐Knol 1987; Kovacs 2010; Labenz 2005; Lauristen 2003; Lind 1999; Lundell 1991; Metz 2003; Nagahara 2014; Norman Hansen 2005; Peura 2009; Peura 2016; Reimer 2010; Richter 2000; Richter 2004; Robinson 1995; Sandmark 1988; Scholten 2005; Sjöstedt 2005; Sontag 1997; Sun 2015; Talley 2001; Talley 2002a; Talley 2002b; Tan 2011; Tsai 2004; Vakil 2001; Valenzuela 1991; Van Rensburg 1996; Van Rensburg 2008; Vantrappen 1988; Van Zyl 2000; Venables 1997; Vigneri 1995; Wulff 1989; Zwisler 2015). Refer to Characteristics of excluded studies table for deprescribing trials that did not meet all inclusion criteria.

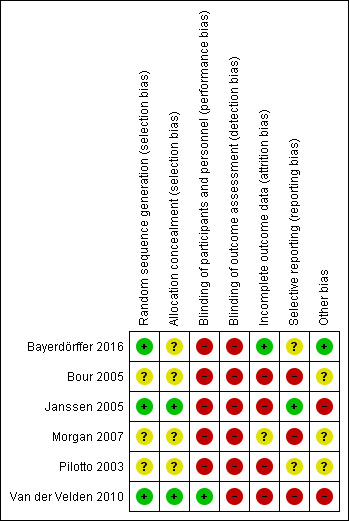

Risk of bias in included studies

See Characteristics of included studies table for study details including all aspects of risk of bias. Figure 2 and Figure 3 provide a visual summary of the risk of bias in included studies presented as percentages across all included studies and for individual studies.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgments about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgments about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Contribution of allocation bias was difficult to determine, as four trials did not describe how they performed allocation (Bayerdörffer 2016; Bour 2005; Morgan 2007; Pilotto 2003). The remaining two trials used sound methods: Janssen 2005 used sealed boxes containing study medication, and participants were allocated according to the numbering in ascending order, while Van der Velden 2010 used a computer‐generated list, enlisted an external party to generate sealed identical containers which were sent to the general practitioners, and participants were allocated the next available number of the set on entry into the trial.

Blinding

Of the six trials included, two trials were double blinded (Pilotto 2003; Van der Velden 2010), although the authors of van der Velden and colleagues noted that the data were analyzed unblinded. Van der Velden 2010 blinded participants by providing identical containers and by providing the control arm with daily dose of PPI plus placebo rescue medication to use as needed and providing the inverse to the intervention group (placebo daily plus PPI when needed). Pilotto 2003 did not comment how blinding was maintained and whether pills looked identical in both arms. The remaining four trials had an open‐label design (Bayerdörffer 2016; Bour 2005; Morgan 2007; Pilotto 2003). Many of the outcomes related to symptom relief, despite use of scales, relied on subjective reporting, and thus were subject to bias. For example, Bour 2005 evaluated participant‐rated symptom relief (primary outcome) using a Likert scale and it was unclear if investigators saw participant satisfaction measures before they assessed satisfaction. Janssen 2005 also measured subjective outcomes (symptom control and satisfaction/unwillingness to continue), creating high risk of bias. However, the objective measure of pill count was unbiased (measurement was not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding). Participant‐rated effect of treatment and satisfaction in the trial by Morgan 2007 were also inherently subject to bias as neither participants nor assessors were blinded.

Incomplete outcome data

Reporting of outcome data revealed a relatively high risk of bias as the majority of trials had participants lost to follow‐up or did not report on all predefined outcomes, or both.

Although the study completion rate was high for Bour 2005 (greater than 80%), the reason for dropout was unclear in all instances and there was a statistically significant higher number of participants who withdrew from the trial for reasons unknown, defined as 'other' in the on‐demand treatment group. Only 67/81 participants were analyzed for pill usage in the continuous treatment group, and only 55/71 for the on‐demand treatment group, with no explanation provided.

Janssen 2005 had a relatively higher dropout rate (22%) but maintained sufficient participation to achieve their power calculation. Although they did not report if characteristics differed between those who stayed in study, versus those who were excluded, the unwillingness to continue as cause of dropout was similar between groups (6% versus 8%) for the long‐term phase.

Morgan 2007 and Pilotto 2003 reported overall dropout rates making it difficult to assess if reasons for withdrawal from the study were similar between treatment and control groups. Endpoints in the Pilotto 2003 trial were not clearly defined, also making it difficult to assess completion of outcome data reporting. Van der Velden 2010 clearly reported dropouts and reasons, however did not comment on whether differences were significant between groups (33% dropout in the on‐demand arm, which was greater than the 20% anticipated). The authors of this study stated that 40 participants were required in each arm (Van der Velden 2010 page 44), though a power calculation was not described. Bour 2005 arbitrarily set a fixed sample size of 200, with no discussion of power or adequate sample size. In total, three of the five trials did not report a power calculation, therefore it is unclear how significant these dropout rates were (Bour 2005; Pilotto 2003; Van der Velden 2010). Bayerdörffer 2016 presented a comprehensive review in their figure two, regarding dropout rates including reasons within in each study arm.

Selective reporting

Van der Velden 2010 appeared to have significant reporting bias for several outcomes because of incomplete reporting of results. Number of rescue pills used weekly was not reported as absolute numbers, but rather participants were divided into groups based on usage that were not defined a‐priori (less than two pills, two to five pills, and six or seven pills weekly). The authors did not predefine how they would assess participant satisfaction. Predefined secondary outcomes of symptom control and quality of life were not assessed separately and rather inferred from results of two surveys (Quality of Life in Reflux and Dyspepsia (QolRad), and SF‐36 Health Survey). The use of a modified per protocol population lead to results that were more difficult to interpret, and additionally, standard deviations (SD) were not reported for all their predefined outcomes.

There was significant bias in the Pilotto 2003 trial, as outcomes were not predefined in their methods and event rates were not reported. Despite methods suggesting that investigators classified symptom severity as mild, moderate, or severe, symptom assessment was only reported as percentage of participants with symptoms. Baseline participant demographics/characteristics were presented as overall numbers rather than for each group, so it is unknown if groups were balanced at randomization and if risk factors in one arm outweighed the other.

Three trials reported all predefined outcomes (Bour 2005; Janssen 2005; Morgan 2007). However, Morgan 2007 combined satisfaction ratings in their results, which was not predefined (e.g. reported results as a combination of 'good' or 'very good' ratings and 'satisfied' or 'very satisfied' ratings). This trial did not report SDs for pill usage. We were unable to use participant satisfaction scale in the meta‐analysis as SDs were not reported for this scale.

Bour 2005 reported additional analysis, but acknowledged the change to their protocol, to include statistical analysis rather than just descriptive data (e.g. subanalysis of relapse rates in different levels of on‐demand use). Janssen 2005 presented comprehensive tables and figures and included means, SDs, event numbers, absolute differences calculated, P values, and CIs. Janssen 2005 reported additional data in the results section although they were not predefined in their study design (e.g. tolerability, number of pills used). Bayerdörffer 2016 addressed all outcomes and reported data for both primary and secondary outcomes.

Other potential sources of bias

The use of perceived mean daily symptom load (MDSL) score by Janssen 2005 could contribute to bias, as this scale was defined by the authors, was not validated, and psychometric properties were unknown. Evaluating bias for the trial published by Pilotto 2003 was challenging as insufficient data were provided to make an accurate assessment.

Five of the six trials listed drug manufacturers as external funding sources: Bour 2005 by Janssen‐Cilag; Morgan 2007 by Janssen‐Ortho; Pilotto 2003 by Pharmacia, Milano, Italy; Van der Velden 2010 by Nycomed BV; and Bayerdörffer 2016 by AstraZeneca. Their role was unclear/unreported in four trials (Bayerdörffer 2016; Bour 2005; Morgan 2007; Pilotto 2003), while Van der Velden 2010 explicitly stated drug manufacturer was not involved in any aspect of participant selection, data collection, analysis, interpretation, writing and submission of manuscript. Janssen 2005 did not list sources of funding.

Effects of interventions

Primary outcomes

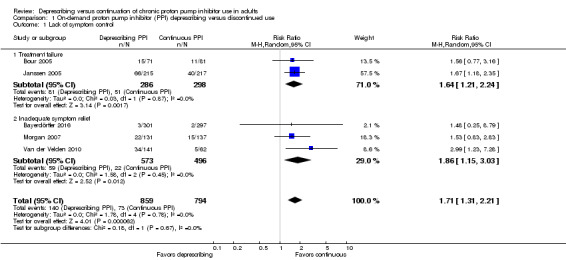

Lack of symptom control

All six studies measured lack of symptom control and they analyzed data separately based on the deprescribing interventions (i.e. (on‐demand therapy) and abrupt discontinuation). Analysis 1.1 summarizes the pooled outcomes (n = 1653) for on‐demand deprescribing versus continuous PPI therapy under the heading of 'Lack of symptom control'. Lack of symptom control was defined as either treatment failure (i.e. return of symptoms) or inadequate symptom relief. Two trials assessed treatment failure (Bour 2005; Janssen 2005). In Janssen 2005, treatment failure was the inverse of rate of symptom relief. In Bour 2005, symptom recurrence was interpreted as treatment failure. Three trials assessed inadequate relief (Bayerdörffer 2016; Morgan 2007; Van der Velden 2010). Van der Velden 2010 and Bayerdörffer 2016 reported dropout rates secondary to inadequate relief. Morgan 2007 reported effect of the study medication on heartburn control as 'good' or 'very good'. The remaining participants were interpreted as having inadequate symptom relief. Intention‐to‐treat (ITT) was used to report event rates, Overall, 16.3% of participants in the on‐demand deprescribing group experienced lack of symptom control versus 9.2% in continuous treatment (RR 1.71, 95% CI 1.31 to 2.21).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 On‐demand proton pump inhibitor (PPI) deprescribing versus discontinued use, Outcome 1 Lack of symptom control.

Pilotto 2003 reported the percentage of participants with return of GI reflux symptoms (i.e. lack of symptom control). The data from this trial were evaluated separately as the deprescribing intervention was stopping PPI (i.e. abrupt discontinuation). From this value, the event rate was extrapolated using ITT (Analysis 2.1). Similarly to on‐demand therapy, abrupt discontinuation was associated with an increased risk in return of GI symptoms. Given that only a single abrupt discontinuation trial reported data for this outcome, firm conclusions cannot be made.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Abrupt discontinuation proton pump inhibitor (PPI) deprescribing versus continued use, Outcome 1 Lack of symptom control.

Drug burden/proton pump inhibitor use

Three studies (n = 1152) evaluated the number of pills used throughout the duration of each trial (Analysis 1.2) (Bayerdörffer 2016; Bour 2005; Janssen 2005). A fourth trial, Van der Velden 2010, reported weekly "rescue" pill use rather than total weekly PPI use. We did not include PPI use data from this trial as there was insufficient reporting of the outcome to allow for inclusion in meta‐analysis.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 On‐demand proton pump inhibitor (PPI) deprescribing versus discontinued use, Outcome 2 Pill use.

All three trials included in the analysis reported mean number of pills used per day (Bayerdörffer 2016; Bour 2005; Janssen 2005). For the purpose of this review, the mean values along with their SD were converted to weekly PPI consumption. Reported means and SDs were multiplied by a factor of seven to convert to total PPI use per week. The overall effect was a mean reduction of PPI use by 3.79 pills per week 95% CI ‐4.73 to ‐2.84 (P < 0.00001). There was significant heterogeneity (I2 greater than 96%).

Cost/resource use

We were unable to perform analyses of cost or resource use because the studies did not report this information.

Secondary outcomes

Positive drug withdrawal events

We were unable to perform analyses of PDWEs because the studies did not report this information.

Adverse drug withdrawal events

Two trials reported ADWEs; one trial had on‐demand deprescribing (Bayerdörffer 2016) and the other abrupt discontinuation (Pilotto 2003). Bayerdörffer 2016 reported 15 participants developing esophagitis in the on‐demand arm while those who continued with daily PPI use did not develop esophagitis (Analysis 1.3). Pilotto 2003 documented healing rates for participants on continuous daily PPI versus placebo (i.e. abrupt discontinuation). Based on healing rates reported, we calculated relapse rates (the inverse) and interpreted them as a marker for ADWE (Analysis 2.2). Overall, 69.6% of participants with a history of esophagitis had a relapse with abrupt discontinuation compared to 20.4% with continuous treatment.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 On‐demand proton pump inhibitor (PPI) deprescribing versus discontinued use, Outcome 3 Adverse drug withdrawal event.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Abrupt discontinuation proton pump inhibitor (PPI) deprescribing versus continued use, Outcome 2 Adverse drug withdrawal events.

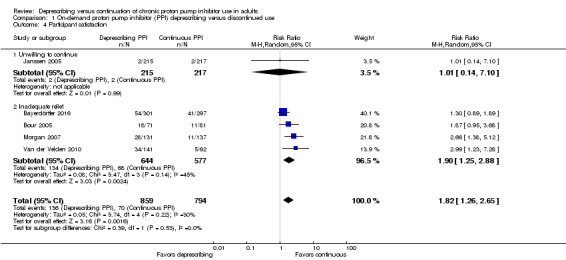

Participant satisfaction

Five studies (n = 1653) evaluated participant satisfaction with on‐demand deprescribing as compared to continuous daily PPI use (Bayerdörffer 2016; Bour 2005; Janssen 2005; Morgan 2007; Van der Velden 2010). Participant satisfaction was interpreted using unwillingness to continue (based on premature discontinuation rates) and inadequate symptom relief (Analysis 1.4). In these studies, participants using PPIs on‐demand had a greater likelihood of being dissatisfied with therapy compared to participants using PPIs continuously (15.8% with on‐demand versus 8.8% with continuous; RR 1.82, 95% CI 1.26 to 2.65).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 On‐demand proton pump inhibitor (PPI) deprescribing versus discontinued use, Outcome 4 Participant satisfaction.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This systematic review summarized the data from six RCTs looking at deprescribing of PPIs versus continuation of chronic daily PPI therapy (Table 1; Table 2). Five trials assessed on‐demand therapy and one trial evaluated the effects of abrupt PPI discontinuation. The majority of the participants had mild GERD with or without low‐grade esophagitis. Our results show an increase in lack of symptom control and participant dissatisfaction with on‐demand deprescribing, though there was a significant reduction in pill use and burden (MD 3.79 pills weekly). Independent of the method of deprescribing, the risk of being dissatisfied with the control of upper GI symptoms was higher in the deprescribing arms. Despite these findings, a proportion of participants tolerated on‐demand therapy, though further studies are required to identify which subpopulation may benefit the most, without putting them at risk of ADWE as was seen with the Pilotto 2003 and Bayerdörffer 2016 trials. It also remains unclear whether deprescribing is effective and safe in people with severe esophagitis, as this population was not captured in the included trials. Unfortunately, we found no trials to satisfy our primary and secondary outcomes of cost and PDWEs.

On‐demand proton pump inhibitor deprescribing

Five trials evaluated deprescribing via an on‐demand approach (Bayerdörffer 2016; Bour 2005; Janssen 2005; Morgan 2007; Van der Velden 2010). Participants were aged 48 to 57 years and either had NERD or a milder form of esophagitis (LA grade A and B or Savary‐Miller grade 1 and 2).

For the primary outcome of change in upper GI symptoms, deprescribing demonstrated a return of symptoms (e.g. heartburn, regurgitation) for a proportion of people. These results were expected as participants in the on‐demand group were instructed to initiate on‐demand PPI use upon sensation of symptoms. In the combined cohort of 1653 participants randomized to on‐demand therapy, approximately 16.3% had either treatment failure or inadequate symptom relief (compared to around 9.2% on continuous PPI therapy, P less than 0.0001). This indicates that while the risk of recurrent symptoms with on‐demand therapy is greater than continuous daily PPI use, the majority of people will still tolerate the intervention. Further studies are required to identify which subpopulations comprise this group.

We pooled data for drug burden/PPI use from three on‐demand trials (n = 1152) (Bayerdörffer 2016; Bour 2005; Janssen 2005). The pooled data favored deprescribing (MD 3.79 pills weekly) and was statistically significant with a P value of less than 0.00001, although heterogeneity was high. The pooled results of this review were consistent with what is currently published in primary literature. Trials evaluating on‐demand PPI use have reported a mean pill consumption of 0.3 pills per day (Bigard 2005; Kaspari 2005; Pace 2008; Ponce 2004; Tsai 2004).

Participant satisfaction was determined by evaluating unwillingness to continue treatment and inadequate symptom relief. Data for this outcome favored chronic PPI use. Interestingly, when assessed individually, not all trials showed a significant difference in participant satisfaction ratings between groups. Janssen 2005, Bour 2005, and Bayerdörffer 2016 had CI value crossing one; however, the overall treatment effect showed significance in favor of deprescribing (RR 1.82, 95% CI 1.26 to 2.65, P < 0.002). One on‐demand PPI trial provided data for unwillingness to continue secondary to inadequate relief, which was interpreted for this review as a marker for participant dissatisfaction (and thus the inverse, as participant satisfaction) (Janssen 2005). The open‐label nature of Janssen 2005 likely influenced the results as participants were aware that they were in control of PPI use and likely favored this method rather than daily PPI use. In past literature, participant satisfaction has been reported to be in favor of chronic PPI use, though the difference from on‐demand therapy is small (Pace 2005). Our results parallel data that have been previously published. We believe that on‐demand therapy could be a viable option for people with NERD or mild‐to‐moderate GERD, without compromising satisfaction of symptom control. Further studies using more targeted measurements of participant satisfaction are needed to confirm or refute these results.

One on‐demand trial had data for ADWE (Bayerdörffer 2016). Participants in this trial were assessed endoscopically before and after randomization. Those who did not present with esophagitis were included and randomized. Investigators performed an endoscopy at the end of the trial to assess the development of esophagitis. It found that 5% (n = 15) of participants using on‐demand PPI developed mild esophagitis (14 with LA grade A, 1 with grade B).

Abrupt discontinuation deprescribing

We identified one trial of abrupt discontinuation (Pilotto 2003). Participants in this trial experienced mild‐to‐moderate esophagitis (Grade 1 or 2), though they were much older than participants taking on‐demand therapy (mean age 73 years). This trial demonstrated a statistically significant increase in the primary outcome of lack of symptom control. Participants experienced return of symptoms, which is expected, as transient and reversible rebound effects have been previously described for both healthy people and people with GI disorders upon abrupt PPI discontinuation (Reimer 2009b). Once again, symptom relapse was not observed in the entire cohort (67.9% in abrupt discontinuation versus 22.4% in the continuous arm), suggesting almost a third of the studied population tolerated abrupt discontinuation.

The Pilotto 2003 trial also addressed the secondary outcome of ADWEs. The trial evaluated changes in endoscopic findings (i.e. healing rates), which were interpreted within this review as relapse rates by assuming the inverse. The results from this trial indicated an increased risk of ADWE with deprescribing (i.e. abrupt discontinuation) that was statistically significant in people with esophagitis grades 1 or 2. Despite these findings, it is difficult to make any conclusions as the results are based on a single study of older adults with mild‐to‐moderate disease. Furthermore, the trial had a small sample size with no reported power or predefined primary endpoints. Current recommendations also suggest avoiding abrupt discontinuation, as relapse acid hypersecretion has been demonstrated even in healthy participants (Reimer 2009b). Other potential ADWEs such as upper GI bleeding or progression of esophagitis to Barrett's esophagus, among others, were not addressed by any of the trials included.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The evidence for PPI use in many indications (e.g. GERD, PUD, SUP) only supports short‐term use (e.g. two to 12 weeks), yet these drugs are commonly continued for prolonged periods or even indefinitely, without appropriate reassessment (Donnellan 2004; Reimer 2009a). Continuous use of PPIs for durations exceeding accepted standards appears to be commonplace, and is likely due to the fact that this class of medication is very well tolerated and considered benign compared to other prescribed medications. This relatively desirable safety profile often overshadows lesser known drug interactions (e.g. hepatic enzyme inhibition, effects on drug absorption or activation) and poorly understood adverse effects and associated risks (vitamin B12 deficiency, hypomagnesemia, CAP, C. difficile infection, diarrhea, headache, and fractures) (Ament 2012; Chubineh 2012; Fohl 2011; Linsky 2013). Although these adverse effects may not be very common and true association with risk is debatable, the extensive use of PPIs in a wide range of populations without monitoring and reassessment is concerning.

The six trials included in this review mimic real world practice as they assessed people with adequate control and symptom relief on chronic daily PPI therapy. The control arm of no change in current daily PPI dose reflects the all too common decision of practitioners and people not to change therapy deemed effective. The deprescribing arms of abrupt discontinuation or on‐demand PPI use represent two of the many options practitioners and people have to minimize medication use and actual or potential adverse effects of chronic PPI therapy.

Unfortunately, the search identified insufficient trials to thoroughly investigate the benefits and harms of deprescribing PPIs. As described in the Background section of this review, there are many other methods of deprescribing that were not captured here. There were also no trials that investigated our primary outcome of burden/resource use, and secondary outcome of PDWE. The systematic review identified many gaps in literature that still need to be addressed. Our literature search captured predominantly people with NERD or mild esophagitis (LA grade A and B, Savary‐Miller grade 1 and 2), which limits the generalizability of results. Outcomes such as PDWE and ADWE are also not well addressed in the literature. In addition, the optimal approach to deprescribing PPIs has not been evaluated (e.g. tapering before stopping). Studies employed different definitions of symptom relapse and participant satisfaction; consistency would be helpful to improve the quality of the body of evidence and should include participant perspective in terms of what is meaningful to them. The data presented in this systematic review were not conclusive; further studies are required to address the gaps in literature.

Quality of the evidence

The quality and strength of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE system (GRADEpro). Overall, the quality of evidence for on‐demand PPI use was very low to moderate. There was serious risk of bias for all outcomes. The quality for the outcome of lack of symptom control was low due to serious imprecision. The quality of evidence for pill use was moderate. Lastly, participant satisfaction evidence was very low in quality due to serious indirectness and imprecision. This further highlights the need for future studies to address the clinical benefits and harms of PPI deprescribing. The quality of the evidence for the abrupt discontinuation deprescribing method was very low due to high risk of bias and wide CIs.

Potential biases in the review process

While we attempted to adhere to sound methodology, this systematic review was not void of limitations. First, as deprescribing is not widely described in the scientific literature, there was potential of not capturing all relevant trials. Although we sought assistance from a specialist librarian to create a filter to capture all trials related to deprescribing, it remained, nonetheless, an unvalidated search strategy. Ideally, a grey literature search would have created a more comprehensive review, however, funding and resources did not allow for this to be investigated. Second, few trials were available to confidently support the objective of this study. This could be due to the strict criteria outlined for the control arm. To satisfy the requirement for a control arm, only RCTs with a minimum run‐in phase of 28 days were considered to fulfil the definition of "chronic PPI use". This criterion was essential to capture true chronic daily PPI users. Additionally, even though eligibility criteria were broad for participants, the trials captured in this systematic review included predominantly people with NERD and mild‐to‐moderate GERD which limits the generalizability of results. All trials were of short duration (less than one year). As such, the long‐term benefits or harms of deprescribing PPIs in chronic users are difficult to extrapolate.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Previous publications outline deprescribing methods for PPIs (Zarowitz 2011); however, there is very little evidence comparing deprescribing modalities to continuous daily PPI use.

With respect to on‐demand therapy, a large body of evidence supports this deprescribing alternative for people with milder forms of GERD (NERD and uninvestigated GERD) (Bytzer 2004; Lee 2004; Morgan 2007; Zacny 2005). One systematic review assessing intermittent and on‐demand acid suppression therapy (e.g. H2RA and PPI) concluded that in people with mild GERD, first treated for four to eight weeks with continuous PPI, a six‐month course of on‐demand therapy was efficacious (Zacny 2005). Of these participants, 70% to 93% were willing to continue treatment with a deprescribing regimen. A more recent Danish review by Haastrup 2014 described six clinical trials (RCT and non‐RCT), using different deprescribing methods (e.g. discontinuation, dose reduction). Indication for PPI use was unknown in two trials, and described as GERD or nonulcer dyspepsia in the remaining four trials. The authors reported PPI discontinuation without deteriorating symptom control ranging from 14% to 64%, with durations of up to one year or more, similar to results of this trial (approximately a third tolerated abrupt discontinuation and 85% tolerated stepdown to on‐demand therapy) (Haastrup 2014).

Another RCT assessed symptom relief in people with GERD treated with on‐demand omeprazole versus continuous therapy (Nagahara 2014). Their results indicated that a greater proportion of people with on‐demand treatment had symptom relief by 24 weeks (74% with on‐demand therapy versus 66.7% continuous therapy), though this was not statistically significant. They concluded that on‐demand treatment in people with NERD would be adequate maintenance therapy and that continuous therapy would be ideal for people with reflux esophagitis.

To date, we identified a single meta‐analysis by Jiang and colleagues designed to compare on‐demand PPI use versus once‐daily PPI therapy (Jiang 2013). This study included two RCTs (Janssen 2005; Tsai 2004; n = 1054). Participants were approximately 50 to 52 years of age and were diagnosed with NERD or GERD classified as Savary‐Miller grade 1. The authors concluded that on‐demand therapy was more effective (i.e. greater proportion of people willing to continue with on‐demand therapy) than daily PPI use.

Our systematic review differed in that we investigate further, and aim to assess both the efficacy and safety, and identify potential benefits and harms of deprescribing PPIs. Our results indicated the opposite of what was published by Jiang and colleagues in that a significant proportion of participants in the on‐demand group were unwilling to continue due to return of GI symptoms. This discrepancy identified gaps in literature, and further trials are required to assess the efficacy, safety, benefits, and harms of deprescribing PPIs.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The results of this review indicate that caution is needed when implementing deprescribing methods for chronic proton pump inhibitor (PPI) users; however, few clear conclusions can be drawn regarding how to best implement PPI deprescribing. On‐demand PPI use may increase risk of symptom relapse compared to continued use, although there may be a subset of people who tolerate the intervention. If on‐demand deprescribing is tolerated, people may see a benefit of reduced pill burden by a mean of up to 3.79 pills per week. With respect the outcome of adverse drug withdrawal events (ADWE), there appears to be an increased risk of rebound esophagitis with on‐demand therapy and abrupt discontinuation, though only two trials reported data in sufficient detail. We identified no trials that allowed for conclusions regarding our primary and secondary outcomes of cost and positive drug withdrawal effects. It is important to bear in mind that the results of this systematic review only apply to people with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) presenting with NERD or mild esophagitis. This excludes people with moderate‐to‐severe esophagitis, Barrett's esophagus, Zollinger‐Ellison syndrome, people with H. pylori, chronic NSAID use, or PUD, to name a few.

Implications for research.