Abstract

Intestinal microbes provide multicellular hosts with nutrients and confer resistance to infection. The delicate balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory mechanisms, essential for gut immune homeostasis, is affected by the composition of the commensal microbial community. Regulatory T (Treg) cells expressing transcription factor Foxp3 play a key role in limiting inflammatory responses in the intestine1. Although specific members of the commensal microbial community have been found to potentiate the generation of anti-inflammatory Treg or pro-inflammatory Th17 cells2-6, the molecular cues driving this process remain elusive. Considering the vital metabolic function afforded by commensal microorganisms, we hypothesized that their metabolic by-products are sensed by cells of the immune system and affect the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory cells. We found that a short-chain fatty acid (SCFA), butyrate, produced by commensal microorganisms during starch fermentation, facilitated extrathymic generation of Treg cells. A boost in Treg cell numbers upon provision of butyrate was due to potentiation of extrathymic differentiation of Treg cells as the observed phenomenon was dependent upon intronic enhancer CNS1, essential for extrathymic, but dispensable for thymic Treg cell differentiation1, 7. In addition to butyrate, de novo Treg cell generation in the periphery was potentiated by propionate, another SCFA of microbial origin capable of HDAC inhibition, but not acetate, lacking this activity. Our results suggest that bacterial metabolites mediate communication between the commensal microbiota and the immune system, affecting the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory mechanisms.

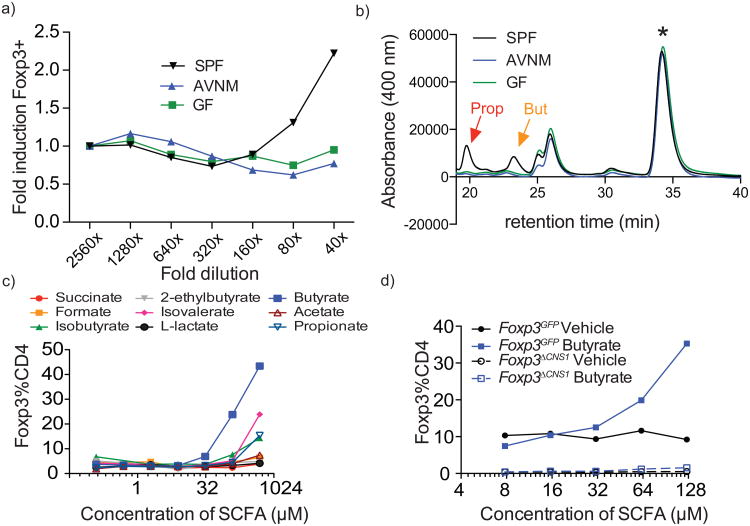

We reasoned that if microbial metabolites facilitate generation of extrathymic Treg cells, such products would be found in the feces of specific pathogen-free (SPF) mice with a normal spectrum of commensal microorganisms, but not microbiota-deficient mice treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics (AVNM) or germ-free (GF) mice. Indeed, we found that polar solvent extracts of feces from SPF, but not GF or AVNM-treated mice potentiated induction of Foxp3 upon stimulation of purified peripheral naïve (CD44loCD62LhiCD25-) CD4+ T cells by CD3 antibody in the presence of dendritic cells (DCs), IL-2, and TGF-β (Fig. 1a). Among bacterial metabolites we expected to find short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), and evaluated their content in fecal extracts from SPF, GF or AVNM-treated mice and their ability to affect Treg cell generation. Analysis of hydrazine-derivatized SCFA by HPLC showed a sharp reduction in propionate and butyrate in extracts from GF and AVNM-treated vs. SPF animals (Fig.1b). Concentrations of these SCFA in extracts were in a 5 mM range, corresponding to ∼100-125 μMin in vitro Foxp3 induction assays (data not shown). Furthermore, purified butyrate, and to a lesser degree isovalerate and propionate, but not acetate, augmented TGF-β-dependent generation of Foxp3+ cells in vitro (Fig. 1c; data not shown). To exclude the possibility that butyrate allowed for expansion of a few contaminating Treg cells in the starting naïve CD4+ T cell population, we took advantage of mice lacking an intronic Foxp3 enhancer CNS1. These mice are selectively impaired in extrathymic Treg cell differentiation while thymic differentiation is intact 1, 7. Butyrate failed to rescue the impaired Foxp3 induction in naïve CD4+ T cells in the absence of CNS1 (Fig. 1d). Consistent with this result, butyrate did not diminish either qualitatively or quantitatively the TGF-β dependence of Foxp3 induction in CNS1-sufficient CD4+T cells (data not shown). These data suggested that butyrate promotes extrathymic differentiation of Treg cells.

Figure 1. SCFA produced by commensal bacteria stimulate in vitro generation of Treg cells.

a) Effect of fecal extracts from SPF, antibiotic-treated (AVNM), or germ-free (GF) mice on in vitro induction of Foxp3 expression in naïve CD4+ T cells stimulated with CD3 antibody in the presence of Flt3L-elicited DC and TGF-β. Foxp3 expression was assessed by flow cytometric analysis on day 4 of culture. Naïve CD25+CD62LhiCD44loCD4+ T cells were FACS-purified from B6 mice. Fecal extracts were prepared in 70% ethanol. Data are shown as fold induction over corresponding dilution of vehicle and are representative of 2 independent experiments.

b) HPLC fractionation of 2-nitrophenylhydrazine-HCl derivatized SCFA present in indicated fecal extracts. Red and yellow arrows indicate peaks corresponding to propionate and butyrate, respectively. Internal standard peak is indicated with a star. The HPLC fractionation profile of fecal extracts pooled from three animals each is representative of two independent experiments.

c) Effect of indicated purified SCFA on in vitro induction of Foxp3 expression in naïve CD4+ T cells isolated from B6 or Foxp3GFP mice as described in (a). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

d) Effect of butyrate on Foxp3 induction in CNS1-sufficient and -deficient naïve CD4+ T cells from Foxp3GFP and Foxp3ΔCNS1 as described in (a). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

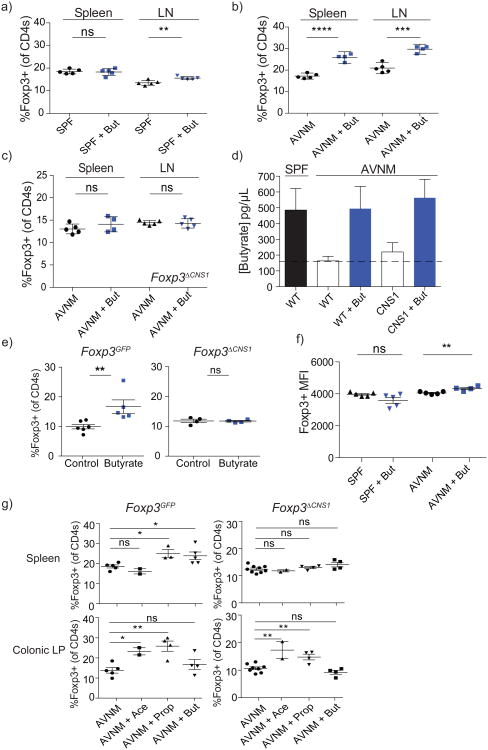

In order to determine if butyrate is capable of promoting extrathymic Treg cell generation in vivo, we administered butyrate in drinking water to AVNM-treated mice, which exhibit a sharp decrease in microbially-derived SCFAs, or untreated control SPF mice. While we detected only very modest changes, if any, in the lymph node and splenic Treg cell subsets in control mice, provision of butyrate to AVNM-treated animals resulted in a robust increase in peripheral, but not thymic or colonic Treg cells (Fig. 2a, b; Supplementary Fig. 1; data not shown). This increase was not an indirect consequence of an inflammatory response because non-lymphoid tissue histology and production of Th1, Th2, and Th17 cytokines by Foxp3-CD4+ T cells remained unchanged upon butyrate treatment (data not shown; Supplementary Fig. 2). In agreement with the observed CNS1 dependence of in vitro Foxp3 induction, provision of butyrate to AVNM-treated CNS1-deficient mice did not increase the proportion or absolute numbers of Treg cells (Fig. 2c; data not shown). Thus, the observed butyrate-mediated increase in the Treg cell subset in vivo was due to increased extrathymic generation of Treg cells and not due to their increased thymic output1, 7. To ensure that butyrate reconstitution did not result in its non-physiologically high levels, we used LC-MS to compare amounts of butyrate in the serum of AVNM-treated mice that received butyrate versus amounts found in control SPF mice. While virtually undetectable in AVNM-treated CNS1-sufficient and -deficient animals, butyrate provision resulted in serum levels comparable to those found in unperturbed SPF mice that did not receive butyrate (Fig. 2d). Consistent with the aforementioned unchanged colonic Treg cell subset in AVNM-treated mice that received butyrate via drinking water, levels of butyrate in fecal pellets were not reconstituted in these mice, likely due to its uptake in the small intestine or stomach (data not shown). In contrast, delivery of butyrate via enema into the colon of CNS1-sufficient, but not CNS1-deficient mice, led to an increase in the Treg cell subset in the colonic lamina propria (LP) (Fig. 2e). Thus, local provision of butyrate promoted CNS1-dependent extrathymic generation of Treg cells in the colon. Furthermore, feeding mice butyrylated starch, in the absence of antibiotic treatment, increased colonic Treg cell subsets in comparison to a control starch diet (Supplementary Fig. 3)8. In addition to increasing Treg cell numbers, restoration of butyrate levels in AVNM-treated animals did not decrease, but instead increased intracellular Foxp3 protein amounts on a per cell basis in both CNS1-sufficient and -deficient mice, suggesting that this bacterial metabolite might also buttress pre-existing Treg cell populations via stabilization of Foxp3 protein expression (Fig. 2f; data not shown).

Figure 2. Butyrate provision promotes extrathymic Treg cell generation in vivo.

a, b) Flow cytometric analysis of Foxp3+ Treg cell subsets in the spleen and lymph nodes (LN) of AVNM-treated (AVNM) or untreated (SPF) B6 or Foxp3GFP mice treated with (+But; blue symbols) or without (black symbols) butyrate in drinking water. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

c) CNS1-deficient mice were treated with AVNM with or without butyrate as in (a) and analyzed for Foxp3 expression in splenic and lymph node (LN) CD4+ T cell populations. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments.

d) LC-MS analysis of butyrate in serum from CNS1-sufficient B6 (WT) and -deficient mice (CNS1) treated as in (a). Serum was derivatized with 2-nitrophenylhydrazine-HCl. Butyrate levels in serum of untreated (SPF) B6 mice are shown in black. Antibiotic-treated (AVNM) WT and CNS1-deficient animals supplemented with (+But; solid bars) or without (empty bars) butyrate are shown. At least 4 mice per group; error bars denote SEM.

e) Flow cytometric analysis of Foxp3+ Treg cell populations in colonic lamina propria of Foxp3GFP (left) and CNS1-deficient mice(right). Mice were administered butyrate (blue symbols) or pH-matched water (control; black symbols) by enema for 7 days and analyzed for Foxp3 expression in colonic CD4+ T cell populations. The data represent the combination of 2 independent experiments; error bars denote SEM.

f) Flow cytometric analysis of Foxp3 protein expression on a per cell basis in splenic Foxp3+ Treg cells in B6 mice treated with butyrate (+But) alone (SPF) or in combination with antibiotics (AVNM) as indicated. The data are shown as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) +/- SD. Data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

g) AVNM-treated Foxp3GFP (left) and CNS1-deficient mice (right) were administered acetate (Ace), propionate (Prop), butyrate (But), or no SCFA (AVNM) for a period of 3 weeks followed by analysis of Foxp3+ Treg cell subsets within CD4+ cells isolated from the colonic lamina propria (top panels) or spleens (bottom panels). Data represent the combination of 2 independent experiments; error bars denote SEM.

* P ≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, *** P ≤ 0.001, **** P ≤ 0.0001 as determined by Student's t-test.

In contrast to butyrate's ability to increase Treg cell generation in the colon only upon local, but not systemic delivery, other SCFA, namely acetate and propionate, were recently shown to promote accumulation of Treg cells in the colon by activating GPR439. These results suggested discrete modes of action of these three SCFAs. To test this idea we administered AVNM-treated CNS1-sufficient and -deficient mice with propionate and acetate in drinking water. Similarly to butyrate, oral provision of propionate increased Treg cell subsets in the spleen in AVNM-treated CNS1-sufficient, but not -deficient animals, suggesting that propionate also promotes de novo generation of peripheral Treg cells (Fig. 2g). In contrast, acetate did not increase splenic Treg cell numbers. These results were fully consistent with our in vitro Treg cell differentiation studies (Fig. 1c). In the colon, however, both acetate and propionate, but not butyrate promoted accumulation of Treg cells in a CNS1-independent manner (Fig. 2g). These results suggest that butyrate promotes de novo generation, but not colonic accumulation of Treg cells, whereas acetate has a diametrically opposite activity and propionate is capable of both.

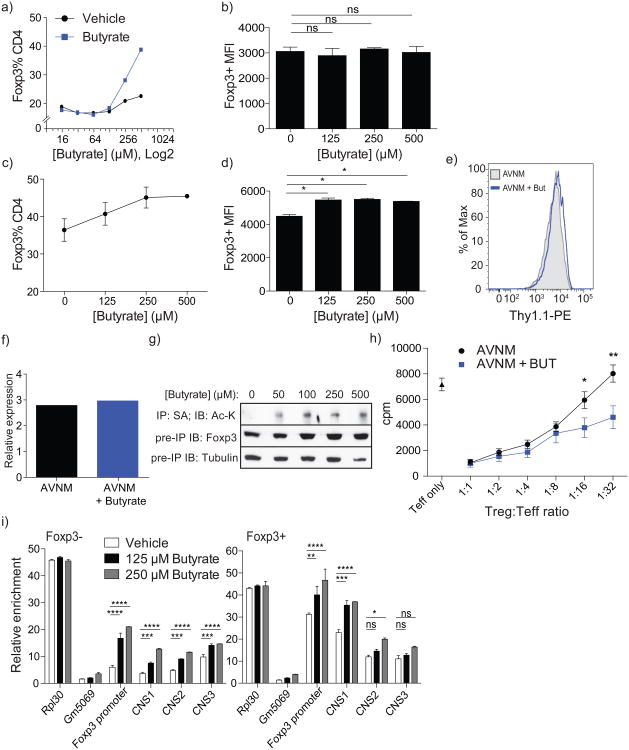

The observation that butyrate facilitates extrathymic differentiation of Treg cells raised a question as to whether butyrate directly affects T cells or DCs (or both)by enhancing their ability to induce Foxp3 expression. To explore these non-mutually exclusive possibilities, we assessed the effects of butyrate on the ability of T cells and DCs to generate Treg cells in vitro (Fig. 3a-d). We found that butyrate increased, albeit modestly (< 1.5-fold), the numbers of Foxp3+cells in DC-free cultures of purified naive CD4+ T cells stimulated by CD3 and CD28 antibody-coated beads and TGF-β (Fig.3c). Like Treg cells isolated from butyrate-treated mice, Treg cells generated in the presence of butyrate in vitro expressed not lower, but rather higher amounts of Foxp3 protein on a per-cell basis than those from butyrate-free cultures (Fig. 3d). This effect was not associated with increased Foxp3 mRNA levels (Fig. 3e, f). Instead, it was likely due to increased Foxp3 protein acetylation observed in the presence of butyrate, a known histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor (Fig. 3g). Foxp3 acetylation confers greater stability and enhanced function 10-13. Furthermore, the suppressor activity of Treg cells isolated from mice treated with AVNM and butyrate was not attenuated, but was moderately enhanced as compared to mice treated with AVNM alone (Fig. 3h).

Figure 3. Butyrate acts within T cells to enhance acetylation of the Foxp3 locus and Foxp3 protein.

a) Induction of Foxp3 expression upon stimulation of naïve CD4+ T cells by CD3 antibody in the presence of butyrate-treated or untreated Flt3L-elicited DC and TGF-β. DC were cultured with titrated amounts of butyrate or medium alone for 6 h, washed and co-cultured with FACS-purified naïve CD4+ T cells in the presence of CD3 antibody and TGF-β. The data are shown as percent CD4+ cells expressing Foxp3 after 4 days of culture. Data are representative of at least 4 independent experiments.

b) Analysis of Foxp3 protein expression on a per-cell basis in Treg cells generated in the presence of butyrate pre-treated Flt3L-elicited DC [as in (a)]. The data are shown as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI); error bars denote SEM.

c) Percent of CD4+ cells expressing Foxp3 after 4 days in FACS-sorted naïve CD4+ T cells incubated with CD3/CD28 antibody-coated beads under Treg-inducing conditions. Data are representative of at least 2 independent experiments; error bars denote SEM.

d) MFI of Foxp3 expression in Foxp3+ CD4+ cells from (c). Data are representative of at least 2 independent experiments; error bars denote SEM.

e) Thy1.1 expression in CD4+Foxp3+ splenocytes isolated from bi-cistronic Foxp3Thy1.1 reporter mice treated with AVNM with (+But) or without butyrate as described in Figure 2a legend. Cell surface expression of IRES-driven Thy1.1 reporter inserted into the endogenous Foxp3 locus reflects Foxp3 mRNA levels. The data are representative of at least 3 mice in each group and 2 independent experiments.

f) CD4+Foxp3+ splenocytes from FoxpGFP reporter mice treated with AVNM with or without butyrate (as in Figure 2a) were FACS-sorted and analyzed for Foxp3 mRNA expression by qPCR.

g) AVI-tagged Foxp3-expressing TCli hybridoma cells were treated for 15 h with butyrate at the indicated concentrations followed by immunoprecipitation of tagged Foxp3 protein using streptavidin beads and immunoblotting for acetylated-lysine residues (top panel), total Foxp3 protein (middle panel) and tubulin (bottom panel) from pre-precipitation whole cell lysate. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments.

h) Analysis of suppressor capacity of GFP+ Treg cells sorted from antibiotic-treated (AVNM) Foxp3GFP mice administered (+But) or not administered butyrate in drinking water. Data represent two independent experiments combined with at least 4 mice per group each.

i) FACS-sorted naïve CD4+ T cells isolated from Foxp3GFP animals were incubated with CD3/CD28 antibody-coated beads under Treg-inducing conditions in the presence of indicated amounts of butyrate. Foxp3+ and Foxp3- CD4+ cells were FACS-purified at day 3 of culture and H3K27 acetylation at the Foxp3 promoter and CNS1-3 enhancers was assessed using ChIP-qPCR. Enrichment over input for each indicated Foxp3 regulatory region at given concentrations of butyrate is shown.

Data in this figure are representative of at least 2 independent experiments. The data represent mean +/- SEM. * P ≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, *** P ≤ 0.001, **** P ≤ 0.0001, as determined by Student's t-test.

Previous in vitro studies suggested that a synthetic HDAC inhibitor, trichostatin A (TSA), potentiates Treg cell generation in vitro by acting on T cells 14, 15. Since butyrate can also boost extrathymic Treg cell generation by acting directly on T cells in the absence of DCs (Fig. 3c), we assessed the effect of butyrate on histone modification at the Foxp3 locus. When naïve CD4+ T cells from Foxp3GFP mice were stimulated by CD3 and CD28 antibody-coated beads and TGF-β with or without butyrate for 3 days, a marked 3-fold increase in H3K27-Ac at the Foxp3 promoter and CNS1 enhancer was observed in Foxp3-cells purified from these cultures (Fig. 3i). In contrast, increases in the H3K27-Ac occupancy in their Foxp3+ counterparts was expectedly minor (∼30%)and inconsequential. Accordingly, Foxp3 mRNA levels were not different in Foxp3+ cells in the presence or absence of butyrate (Fig. 3e,f). Although we cannot discriminate between the contribution of increased acetylation of histone vs. non-histone targets to heightened Foxp3 induction, it is likely facilitated by the increase in H3K27-Ac observed in Foxp3-T cells.

In addition to its direct Treg cell differentiation-promoting effects on CD4+ T cell precursors, butyrate endowed DCs with a superior ability to facilitate Treg cell differentiation. Pretreatment of DCs with butyrate in vitro for 6 h followed by its removal markedly enhanced their ability to induce Foxp3 expression in naïve CD4+ T cells stimulated by CD3 antibody and TGF-β in the absence of butyrate (Fig. 3a; Supplementary Fig. 4a, b). The latter treatment had no detrimental effect on DC viability (Supplementary Fig. 4c). The Foxp3 protein expression induced by butyrate-pretreated and control DCs was comparable, in contrast to a T cell-intrinsic effect of butyrate leading to increased amounts of Foxp3 protein in Treg cells in mice treated with AVNM and butyrate (Fig. 3b, Fig. 2f).

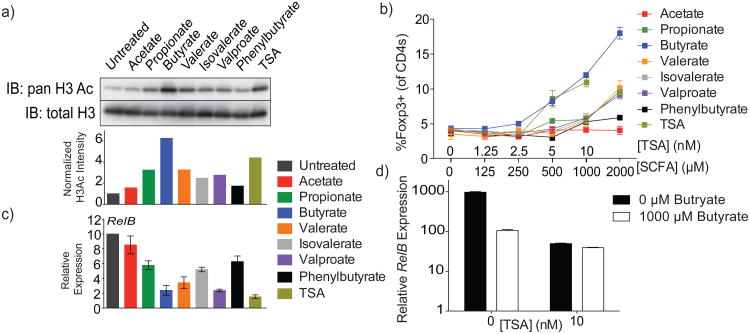

We considered butyrate sensing by G protein-coupled receptors (GPR) as a potential mechanism for the increase in extrathymic differentiation of Treg cells16, 17. However, pre-treatment of Gpr109a+/+ and Gpr109a-/- DCs with butyrate similarly increased in vitro generation of Foxp3+ cells (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Consistent with these results, butyrate-dependent potentiation of Foxp3 induction by DCs remained unchanged upon pretreatment with pertussis toxin (Supplementary Fig. 5b)18. Next, we tested HDAC inhibitory activity of butyrate and other SCFAs in DCs using histone H3 acetylation as an indirect readout (Fig. 4a). TSA and valproate, two chemically distinct HDAC inhibitors, and phenylbutyrate, a butyrate derivative with a relatively weak inhibitory activity, were used as controls in these experiments. Relative HDAC inhibitory activity of SCFAs closely correlated with their ability to potentiate the capacity of DCs to induce Treg cell differentiation. DCs briefly exposed to butyrate, TSA, and to a lesser extent propionate, but not acetate, potently induced Foxp3 expression (Fig.4b). Furthermore, microarray analysis showed that butyrate and TSA induced remarkably similar, if not identical, gene expression changes in DCs (Supplementary Fig. 6a) with a systemic repression of LPS response genes including Il12, Il6, and Relb (Supplementary Fig. 6b,c). Interestingly, repression of Relb, a major inducer of DC activation, correlated with the level of HDAC-inhibitory activity of butyrate and other SCFAs (Fig. 4c)19. Notably, knockdown of RelB in DC promotes their ability to support Treg cell differentiation20, 21. To further ascertain that TSA and butyrate potentiated Treg cell generation through HDAC inhibition and not through distinct independent mechanisms, we treated DCs with the combination of butyrate and optimal amounts of TSA. If butyrate and TSA were to act via independent mechanisms, they should have exhibited synergistic effects on Foxp3 induction. However, if they acted on identical or related targets, i.e. HDACs, additive effects were unlikely. In support of the latter scenario, we found that butyrate was unable to further enhance the ability of TSA to down-regulate Relb and promote Foxp3 induction (Fig. 4d; Supplementary Fig. 6d). These results are consistent with the idea that the HDAC inhibitory activity of butyrate as well as propionate contributes to the ability of DCs to facilitate extrathymic Treg cell differentiation.

Figure 4. HDAC-inhibitory activity of butyrate decreases pro-inflammatory cytokine expression within DC to promote Treg induction.

a) Histone acetylation in Flt3L-elicited DC from B6 mice treated with the indicated SCFA (500 μM) or TSA (10 nM) for 6 h followed by acid extraction of histones from isolated nuclei, SDS-PAGE and blotting with antibody for pan-acetylated H3. Total histone H3 served as a loading control. Shown below is the relative acetylated H3 band intensity calculated over total H3 and normalized as fold over untreated.

b) Induction of Foxp3 expression upon stimulation of naïve CD4+ T cells by CD3 antibody in the presence of SCFA or TSA, Flt3L-elicited DC and TGF-β. DC were cultured with titrated amounts SCFA or TSA for 6 h, washed and co-cultured with FACS-purified naïve CD4+ T cells in the presence of CD3 antibody and TGF-β. The data are shown as percent CD4+ cells expressing Foxp3 after 4 days of culture. Data are representative of at least 2 independent experiments.

c) RelB gene expression quantified by qPCR in purified Flt3L-elicited DC from B6 mice treated for 6 h with SCFA or TSA, as in (a). Data are representative of 4 independent experiments.

d) RelB gene expression quantified by qPCR in purified Flt3L-elicited DC from B6 mice treated with or without TSA in combination with, or in the absence of, butyrate at the indicated concentrations.

Data in this figure are representative of at least 2 independent experiments, unless otherwise noted. The data represent mean +/- SEM.

In conclusion, our studies suggest that butyrate and propionate, produced by commensal microorganisms, increased extrathymic CNS1-dependent differentiation of Treg cells. Our results indicate that metabolic by-products of commensal microorganisms influence the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory cells and serve as a means of communication between the commensal microbial community and the immune system.

Methods Summary

CNS1KO (Foxp3ΔCNS1), Foxp3GFP, Foxp3Thy1.1 and Foxp3DTR mice were previously described7, 22, 23. Male C57BL/6 (B6) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. and groups of 5 co-housed mice were randomly assigned to treatment vs. control groups after confirmation that age and weight were in accordance between groups. Male mice were used for all experiments. All strains were maintained in the Sloan-Kettering Institute animal facility in accordance with institutional guidelines. For antibiotic treatment, mice were given 1 g L−1 metronidazole (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.5 g L−1 vancomycin (Hospira), 1 g L−1 ampicillin (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 g L−1 kanamycin (Fisher Scientific) in drinking water (AVNM). For butyrate, acetate and propionate administration, each SCFA was added to AVNM-containing drinking water at 36 mM and pH-adjusted as needed. DCs were expanded in vivo by subcutaneous injection of B16 melanoma cells secreting FLT3-ligand and purified using CD11c (N418) magnetic beads (Dynabeads, Invitrogen). In vitro Foxp3 induction assays were performed by incubating 5.5 × 104 FACS-sorted naïve CD44loCD62LhiCD25-CD4+T cells with 1 μg ml−1 of CD3 antibodyin the presence of DCsin 96-well flat-bottom plates for 4 d. Alternatively, naïve CD4+T cells were stimulated with CD3 and CD28 antibody-coated beads (Dynabeads Mouse T-Activator, Invitrogen) at a 1:1 cell-to-bead ratio. All cultures were supplemented with 1 ng mL-1 TGF-β and 100 U ml−1 IL-2. Intracellular staining for IL-17, IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-13 and Foxp3 was performed using the Foxp3 staining kit (eBiosciences). Cytokine staining was performed after re-stimulation of ex vivo isolated cells with 5 μg ml−1 CD3 antibody and 5 μg ml−1 CD28 antibody in the presence of Golgi-plug (BD Biosciences) for 5 h. Stool samples were collected directly into sterile tubes from live mice and snap-frozen before preparation of material for SCFA quantification by HPLC or LC-MS. HPLC analysis of 2-nitrophenylhydrazine HCl-derivatized SCFA present in stool extracts was performed as describedelsewhere 24. H3K27Ac ChIP-qPCR was performed as previously described25.

Methods

Mice

Foxp3ΔCNS1 (CNS1 knockout), Foxp3GFP, Foxp3Thy1.1 and Gpr109a-/- mice have been previously described7, 22, 23. Male C57BL/6 (B6) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory and groups of 5 co-housed mice were randomly assigned to treatment vs. control groups after confirmation that age and weight were in accordance between groups. Male mice were used for all experiments. All strains were maintained in the Sloan-Kettering Institute animal facility in accordance with institutional guidelines. Mice were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation then blindly processed for tissue harvest thereafter. For antibiotic treatment, mice at 5-6 weeks of age were treated with 1 g L−1 metronidazole (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.5 g L−1 vancomycin (Hospira), 1 g L−1 ampicillin (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 g L−1 kanamycin (Fisher Scientific) dissolved in drinking water. For butyrate, acetate and propionate administration, each SCFA was added to drinking water containing antibiotics (as described above) at a final concentration of 36 mM and pH-adjusted, if needed, to match that of antibiotic-only water. Butyrate was administered to mice after prior treatment with antibiotics for at least 1 wk.

Cell isolation and FACS staining

For in vitro experiments, CD4+ T cells and CD11c+ dendritic cells were enriched using mouse CD4 (L3T4, Invitrogen) and mouse CD11c (N418, BioLegend) antibodies, respectively, that were biotinylated for use with streptavidin-Dynabeads (Invitrogen). Enriched cells were then sorted on a FACSAria II cell sorter (BD Biosciences) for in vitro assays. Intracellular staining for IL-17, IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-13 and Foxp3 was performed using the Foxp3 staining kit (eBiosciences). Cytokine staining was performed after re-stimulation with CD3 antibody and CD28 antibody(5 μg ml−1 each) in the presence of Golgi-plug (BD Biosciences) for 5 h.

Dendritic cellgeneration and isolation

DC were expanded in vivo by subcutaneous injection of B16 melanoma cells secreting FLT3-ligand into the left hind flank of mice as indicated. Once tumors were visible, spleens from injected animals were dissociated in RPMI 1640 medium containing 1.67 U mL-1 liberase TL (Roche) and 50 μg mL-1 DNAse I (Roche) for 20 min at 37 °C with shaking. EDTA was then added at a final concentration of 5 mM to stop digestion and the resulting homogenate was processed for CD11c+ cell isolation using the MACS mouse CD11c (N418) purification kit (Miltenyi Biotec).

In vitro assays

In vitro Foxp3 induction assays were performed by co-culturing DC with 5.5 × 104 CD4+CD44loCD62LhiCD25- naïve T cells in the presence of 1 μg ml−1 of CD3 antibody, 1 ng mL-1 TGF-β, and 100 U ml−1 IL-2, in 96-well flat-bottom plates for 4 d. For Foxp3 induction in the presence of butyrate- or TSA-pretreated DC, TGF-β was used at 0.1 ng mL-1 final concentration. In vitro induction assays in the absence of DC were performed by incubating 5.5 × 104 naïve CD4+ T cells with 1 ng mL-1 TGF-β, 100 U ml−1 IL-2, and a 1:1 cell-to-bead ratio of CD3/CD28 T activator Dynabeads (Invitrogen). For in vitro suppression assays, 4 × 104 naïve CD4+ T cells were FACS-sorted from B6 mice and cultured with graded numbers of CD4+Foxp3+ Treg cells FACS-sorted from Foxp3GFP mice treated with antibiotics and with or without butyrate, in the presence of 105 irradiated T cell-depleted splenocytes and 1 μg ml−1 CD3 antibody in a 96-well round-bottom plate for 80 h. Proliferation of T cells was assessed by [3H]-thymidine incorporation during the final 8 h of culture.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-qPCR assays

H3K27Ac ChIP-qPCR was performed as previously described25. Briefly, fixed cells were lysed and mono- and poly-nucleosomes were obtained by partial digestion with micrococcal nuclease (12,000 U mL-1) in 1 min at 37 °C. EDTA was added to a final concentration of 50 mM to stop the reaction, and digested nuclei were resuspended in nuclear lysis buffer with 1% SDS. After sonication, 1 ug H3K27Ac-specific antibody (Abcam, ab4729) was used to precipitate H3K27Ac-bound chromatin. Washing and de-crosslinking was performed as described25.

Stool sample collection

Stool samples were collected directly into sterile tubes from live mice and snap-frozen before preparation of material for SCFA quantification by HPLC or LC-MS (see corresponding section for further sample processing).

HPLC assays

HPLC analysis was performed for analysis of derivatized stool extracts as previously described24. Briefly, flash-frozen stool samples were extracted with 70% ethanol and brought to a final concentration of 0.1 μg μL-1. Debris was removed by centrifugation and 300μL of supernatant was transferred to a new tube and combined with 50 μL of internal standard (2-ethylbutyric acid, 200 mM in 50% aqueous methanol), 300μL of dehydrated pyridine 3% v/v (Wako) in ethanol, 300 μL of 250 mM N-(3-dimethlaminopropyl)-N′;-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich) in ethanol, and 300 μL of 20 mM 2-nitrophenylhydrazine hydrochloride (Tokyo Chemical) in ethanol. Samples were incubated at 60 °C for 20 min and 200 μL of potassium hydroxide 15% w/v dissolved 80/20 in methanol was added to stop the derivatization reaction. Samples were incubated again at 60 °C for 20 min and transferred into a glass conical tube containing 3 mL of 0.5 M phosphoric acid. The organic phase was extracted by shaking with 4 mL diethyl ether and transferred to a new glass conical containing water to extract any remaining aqueous compounds. The organic phase containing the derivatized SCFA was transferred into a new 5 mL glass vial and evaporated overnight in a fume hood. Derivatized SCFA were resuspended in 100 μL of mobile phase (below) and 20 μL was chromatographed on a Shimadzu HPLC system equipped with a Vydac 2.1 × 30 mm 300 A C18 column run at 200 μL min-1 in methanol/acetonitrile/TFA (30%/16%/0.1% v/v) and monitored for absorbance at 400 nm.

LC-MS assays

300 μl 80% methanol containing deuterated short chain fatty acid internal standards (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories) was added to 70 μL serum and incubated at −80 °C for 30 min. Samples were then centrifuged at 4 °C at 14000 rpm for 15 min to precipitate protein. Pure short chain fatty acid standards (Sigma-Aldrich) were also prepared in 300 μl 80% methanol containing internal standards to produce a calibration curve from 0.25 μM to 50 μM. 80% methanol extracts were combined with 300 μl 250 mM N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride in ethanol, 300 μL 20 mM 2-nitrophenylhydrazine hydrochloride in ethanol and 300 μL 3% pyridine in ethanol in a glass tube and reacted at 60°C for 20 min. The reaction was quenched with 200 μL potassium hydroxide solution (15% KOH : MeOH, 8 : 2 v/v) at 60°C for 20 min. After cooling, the mixture was adjusted to pH 4 with 0.25 M HCl. Derivatized short chain fatty acids were then extracted with 4 mL ether and washed with 4 mL water before drying under a nitrogen stream. The dried sample was dissolved in 150 μL methanol, and 5 μL was injected for LC-MS analysis.

Butyrate enemas

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and injected intrarectally with 200 μL of 50 mM butyric acid (pH 4.0) or pH-matched water delivered through a 1.2 mm-diameter polyurethane catheter (Access Technologies, Skokie, IL). Enemas were administered for 7 days.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Robert Black Fellowship of the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation DRG-2143-13 (N.A.), Ludwig Center at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant T32 A1007621 (N. A.) and R37 AI034206 (A.Y.R.). A.Y. Rudensky is an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Author Contributions: N.A., C.C. and X.F. performed experiments and analyzed data, with assistance from P.D. with HPLC, P.J.C. with Foxp3-Ac immunoprecipitation and J.V. with ChIP-qPCR experiments. H.L. and J.R.C. performed LC-MS. N.A., C.C., X.F. and A.Y.R. designed and interpreted experiments. K.P. provided Gpr109a mice. N.A. and A.Y.R. wrote the paper.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Josefowicz SZ, et al. Extrathymically generated regulatory T cells control mucosal T(H)2 inflammation. Nature. 2012;482:395–U1510. doi: 10.1038/nature10772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Round JL, Mazmanian SK. Inducible Foxp (3+) regulatory T-cell development by a commensal bacterium of the intestinal microbiota. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:12204–12209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909122107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ivanov II, et al. Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell. 2009;13998:485. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lathrop SK, et al. Peripheral education of the immune system by colonic commensal microbiota. Nature. 2011;478:250–4. doi: 10.1038/nature10434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atarashi K, et al. Induction of Colonic Regulatory T Cells by Indigenous Clostridium Species. Science. 2011;331:337–341. doi: 10.1126/science.1198469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atarashi K, et al. Treg induction by a rationally selected mixture of Clostridia strains from the human microbiota. Nature. 2013;500:232–6. doi: 10.1038/nature12331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng Y, et al. Role of conserved non-coding DNA elements in the Foxp3 gene in regulatory T-cell fate. Nature. 2010;463:808–12. doi: 10.1038/nature08750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Annison G, Illman RJ, Topping DL. Acetylated, propionylated or butyrylated starches raise large bowel short-chain fatty acids preferentially when fed to rats. J Nutr. 2003;133:3523–8. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.11.3523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith PM, et al. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science. 2013;341:569–73. doi: 10.1126/science.1241165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Loosdregt J, et al. Rapid temporal control of Foxp3 protein degradation by sirtuin-1. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Loosdregt J, et al. Regulation of Treg functionality by acetylation-mediated Foxp3 protein stabilization. Blood. 2010;115:965–74. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-207118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang H, Xiao Y, Zhu Z, Li B, Greene MI. Immune regulation by histone deacetylases: a focus on the alteration of FOXP3 activity. Immunol Cell Biol. 2012;90:95–100. doi: 10.1038/icb.2011.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song X, et al. Structural and biological features of FOXP3 dimerization relevant to regulatory T cell function. Cell Rep. 2012;1:665–75. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang L, de Zoeten EF, Greene MI, Hancock WW. Immunomodulatory effects of deacetylase inhibitors: therapeutic targeting of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:969–81. doi: 10.1038/nrd3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tao R, et al. Deacetylase inhibition promotes the generation and function of regulatory T cells. Nat Med. 2007;13:1299–307. doi: 10.1038/nm1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maslowski KM, et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature. 2009;461:1282–U119. doi: 10.1038/nature08530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thangaraju M, et al. GPR109A is a G-protein-coupled receptor for the bacterial fermentation product butyrate and functions as a tumor suppressor in colon. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2826–32. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nilsson NE, Kotarsky K, Owman C, Olde B. Identification of a free fatty acid receptor, FFA2R, expressed on leukocytes and activated by short-chain fatty acids. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;303:1047–52. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00488-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacDonald KP, et al. Effector and regulatory T-cell function is differentially regulated by RelB within antigen-presenting cells during GVHD. Blood. 2007;109:5049–57. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-067249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu HC, et al. Tolerogenic dendritic cells generated by RelB silencing using shRNA prevent acute rejection. Cell Immunol. 2012;274:12–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shih VF, et al. Control of RelB during dendritic cell activation integrates canonical and noncanonical NF-kappaB pathways. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:1162–70. doi: 10.1038/ni.2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fontenot JD, et al. Regulatory T cell lineage specification by the forkhead transcription factor foxp3. Immunity. 2005;22:329–41. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim JM, Rasmussen JP, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells prevent catastrophic autoimmunity throughout the lifespan of mice. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:191–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torii T, et al. Measurement of short-chain fatty acids in human faeces using high-performance liquid chromatography: specimen stability. Annals of Clinical Biochemistry. 2010;47:447–452. doi: 10.1258/acb.2010.010047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samstein RM, et al. Foxp3 exploits a pre-existent enhancer landscape for regulatory T cell lineage specification. Cell. 2012;151:153–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.