Abstract

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) has proven to be most useful for the identification of microorganisms. However, species-specific oligonucleotide probes often fail to give satisfactory results. Among the causes leading to low hybridization signals is the reduced accessibility of the targeted rRNA site to the oligonucleotide, mainly for structural reasons. In this study we used flow cytometry to determine whole-cell fluorescence intensities with a set of 32 Cy3-labeled oligonucleotide probes covering the full length of the D1 and D2 domains in the 26S rRNA of Saccharomyces cerevisiae PYCC 4455T. The brightest signal was obtained with a probe complementary to positions 223 to 240. Almost half of the probes conferred a fluorescence intensity above 60% of the maximum, whereas only one probe could hardly detect the cells. The accessibility map based on the results obtained can be extrapolated to other yeasts, as shown experimentally with 27 additional species (14 ascomycetes and 13 basidiomycetes). This work contributes to a more rational design of species-specific probes for yeast identification and monitoring.

In the last decade, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) became the method of choice for the direct detection and identification of microorganisms in their natural environments (1, 3, 15). Even though FISH has been extensively used in ecological studies of bacteria (3) and other organisms (17), work with fungi has been restricted to the detection of Aureobasidium pullulans on the phylloplane (12, 19) and either clinically relevant or food spoilage yeasts (9, 10, 13, 14). Recently, a method using fluorescently labeled peptide nucleic acid probes was applied with success to the detection of Dekkera bruxellensis in wine (20), to the differentiation between Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis (16), and to direct detection of C. albicans in blood culture bottles (18).

Preliminary studies with yeasts have shown that FISH assays are rapid and simple to carry out, do not require special cell permeation treatments and result in a high signal-to-noise ratio even when the cellular ribosome content is low, e.g., in late-stationary-phase cells (J. Inácio et al., unpublished data). However, a significant fraction of the probes designed yield low or no hybridization signals under optimal experimental conditions as assessed with a universal probe (10). One possible limitation of the method is associated with the target molecule, the rRNA. The targeted region of the ribosomes, which remain in the intact cell, might be structurally hindered or involved in molecular interactions, rendering it inaccessible to probe hybridization (3). Despite the development of procedures to improve the accessibility of those regions by using unlabeled helper oligonucleotides (6), a very useful clue when trying to design a good probe is to look for target sites located in rRNA regions already known to be accessible (7, 8).

The D1 and D2 domains at the 5′ end of 26S rRNA show a high degree of interspecies sequence variation for yeasts and are therefore frequently used for identification as well as in phylogenetic studies (5, 11). Due to the nucleotide sequence variability and to the large number of sequences available in public databases, this region provides an excellent basis to design species-specific FISH probes targeting the rRNAs of yeasts (16, 20).

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the accessibility of the D1 and D2 domains in the 26S rRNA to fluorescently labeled probes by using Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cultivation.

S. cerevisiae PYCC 4455T (Portuguese Yeast Culture Collection, Caparica, Portugal) was grown aerobically under continuous shaking in YM broth (malt extract, 0.3% [wt/vol]; yeast extract, 0.2%; peptone, 0.5%; glucose, 1%) at 25°C. Cells were harvested in the exponential growth phase (optical density of 2.5 at 600 nm) by centrifugation for 5 min at 4,500 × g. Cells were washed once with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (130 mM sodium chloride, 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer [pH 7.2]) and fixed for 4 h with 4% (vol/vol) paraformaldehyde at 4°C (2).

Probe design.

Oligonucleotide probes were designed to cover the full length of the 26S rRNA D1 and D2 domains of S. cerevisiae (Fig. 1) (sequence retrieved from GenBank under accession number U44806). The sequences and positions of the 32 probes in the D1 and D2 domains are listed in Table 1. The standard probe length of 18 nucleotides was varied if the estimated dissociation temperature (Td), according to the formula of Suggs et al. (21) [Td = 4 × (G + C) + 2 × (A + T)], exceeded 60°C or was below 48°C.

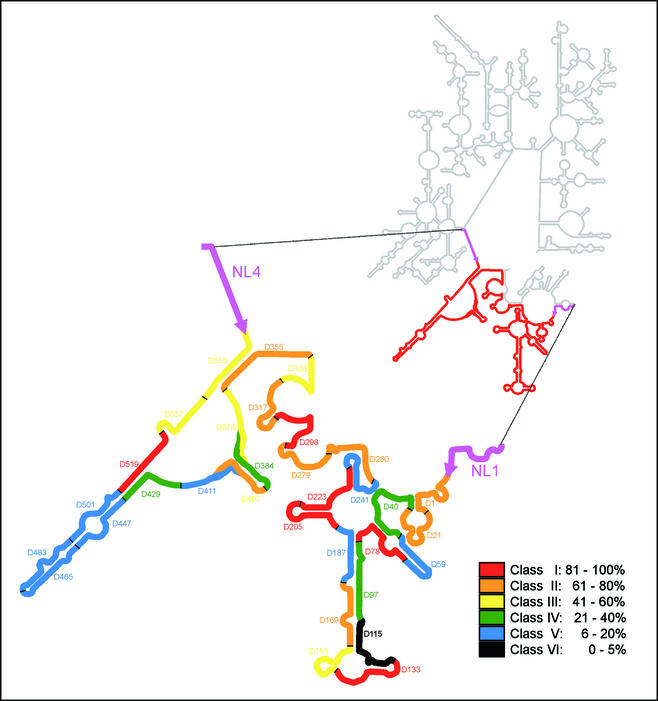

FIG. 1.

Fluorescence intensities of all oligonucleotide probes, standardized to that of the brightest probe (D-223), indicated in a model of the S. cerevisiae 26S rRNA secondary structure in which the D1 and D2 domains (delimited by the NL1 and NL4 primer target sites) are enlarged. The color coding indicates differences in the level of Cy3 probe-conferred fluorescence. The secondary structure is adapted from the European rRNA database (http://rrna.uia.ac.be).

TABLE 1.

Sequences, relative fluorescence intensities, and brightness classes of a set of Cy3-labeled oligonucleotide probes targeting the S. cerevisiae 26S rRNA D1 and D2 domains

| Probe name | S. cerevisiae D1-D2 position (5′→3′) | Probe sequence (5′→3′) | Relative probe fluores- cence (%)a | Bright- ness class |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-1 | 1-20 | AAGGCAATCCCGGTTGGTTT | 67 | II |

| D-21 | 21-39 | CGCTTCACTCGCCGTTACT | 71 | II |

| D-40 | 40-58 | TTCAAATTTGAGCTTTTGC | 32 | IV |

| D-59 | 59-77 | GGCACCGAAGGTACCAGAT | 15 | V |

| D-78 | 78-96 | CTCTCCAAATTACAACTCG | 96 | I |

| D-97 | 97-114 | AACGGCCCCAAAGTTGCC | 39 | IV |

| D-115 | 115-132 | CAAGGAACATAGACAAGG | 4 | VI |

| D-133 | 133-150 | CTCTATGACGTCCTGTTC | 81 | I |

| D-151 | 151-168 | CCACACGGGATTCTCACC | 44 | III |

| D-169 | 169-186 | AAAGAACCGCACTCCTCG | 66 | II |

| D-187 | 187-204 | TCTTCGAAGGCACTTTAC | 17 | V |

| D-205 | 205-222 | ATTCCCAAACAACTCGAC | 84 | I |

| D-223 | 223-240 | CCACCCACTTAGAGCTGC | 100 | I |

| D-241 | 241-259 | TAGCTTTAGATGGAATTTA | 18 | V |

| D-260 | 260-278 | TCGGTCTCTCGCCAATATT | 66 | II |

| D-279 | 279-297 | TCACTGTACTTGTTCGCTA | 79 | II |

| D-298 | 298-316 | AGTTCTTTTCATCTTTCCA | 84 | I |

| D-317 | 317-335 | TTTTTCACTCTCTTTTCAA | 74 | II |

| D-336 | 336-354 | TTTCAACAATTTCACGTAC | 55 | III |

| D-355 | 355-373 | CTGATCAAATGCCCTTCCC | 69 | II |

| D-374 | 374-392 | AGGGCACAAAACACCATGT | 48 | III |

| D-384 | 384-401 | AAGGAGCAGAGGGCACAA | 30 | IV |

| D-402 | 402-419 | CGAGATTCCCCTACCCAC | 61 | II |

| D-411 | 411-428 | AGTGAAATGCGAGATTCC | 13 | V |

| D-429 | 429-446 | CAAAACTGATGCTGGCCC | 24 | IV |

| D-447 | 447-464 | ATGGATTTATCCTGCCAC | 7 | V |

| D-465 | 465-482 | GAGGCAAGCTACATTCCT | 16 | V |

| D-483 | 483-500 | CAGGCTATAATACTTACC | 6 | V |

| D-501 | 501-518 | CAGCTGGCAGTATTCCCA | 7 | V |

| D-519 | 519-536 | CGTCGCAGTCCTCAGTCC | 83 | I |

| D-537 | 537-554 | GCCAGCATCCTTGACTTA | 48 | III |

| D-555 | 555-572 | GCGGCATATAACCATTAT | 55 | III |

Fluorescence intensities expressed as a percentage of the value obtained for the brightest probe detected, D-223.

Probe labeling and quality control.

Probes were synthesized monolabeled at the 5′ end with Cy3 by Interactiva GmbH (Ulm, Germany). Aliquots of each probe were analyzed in a spectrophotometer (UV-1202; Shimadzu, Duisburg, Germany). The peak ratios of the absorption of DNA at 260 nm and the dye at 545 nm were determined in order to check the labeling quality of the oligonucleotides (7).

FISH.

Approximately 106 cells were hybridized in 80 μl of hybridization buffer (0.9 M sodium chloride, 0.01% [wt/vol] sodium dodecyl sulfate, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.2]) with 1.5 ng of Cy3-labeled probe μl−1 at 46°C for 2 h. After incubation, cells were pelleted by centrifugation and the supernatant was discarded. Cells were resuspended in 100 μl of prewarmed hybridization buffer without probe. After washing for 30 min at 46°C, the suspension was mixed with 200 μl of 1× PBS, placed on ice, and analyzed within 3 h.

Flow cytometry.

Fluorescence of hybridized cells was quantified with a FACStar Plus flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, Calif.). The argon ion laser was tuned to an output power of 750 mW at 514 nm. Forward-angle light scatter (FSC) was detected with a 530 (± 30)-nm band pass filter (BD Biosciences). Fluorescence (FL1) was detected with a 620 (± 60)-nm band pass filter (Gesellschaft für dünne Schichten mbH, Hugo Anders, Nabburg, Germany). Cy3 probes were measured with deionized water as sheath fluid, and polychromatic, 0.5-μm-pore-size polystyrene beads (catalog no. 18660; Polysciences, Warrington, Pa.) were used to check the stability of the optical alignment of the flow cytometer and to standardize the fluorescence intensities of hybridized cells (7, 8).

Data acquisition and processing.

The parameters FSC and FL1 were recorded, and for each measurement 10,000 events were stored in list mode files. The CellQuest software (BD Biosciences) was used for subsequent analysis. Probe-conferred fluorescence was determined as the mean of the fluorescence values of single cells recorded in a gate that was defined in an FSC-versus-FL1 dot plot. For every group of 10 measurements, the fluorescence of the reference beads was determined. The standardized cell probe-conferred fluorescence was obtained by dividing the probe values by the fluorescence values of the reference beads. All values were finally expressed relative to the value for the brightest probe detected (Table 1). FISH experiments were performed three times for each probe, on three different days, with independent triplicates in each experiment. Only triplicate values with a standard deviation of below 10% were accepted. The final value for each probe is the mean from at least two independent experiments, with a standard deviation of below 15%. This procedure was adopted to account for the daily variations due to the equipment (e.g., oven temperature and flow cytometer laser power) and user-dependent errors.

Estimation of nucleotide substitution rates for the D1 and D2 domains.

The nucleotide substitution rate, defined as the number of nucleotide substitutions per site and per unit time in the DNA sequence, provides a relative measure of the conservation or variability of the positions analyzed. An alignment of 145 D1 and D2 sequences, reported for yeasts and fungi of different phylogenetic groups (Table 2), was obtained with Megalign (DNAStar, Madison, Wis.) and checked visually. The nucleotide substitution rate for each position in the alignment was estimated by using the software package TREECON (23) and the substitution rate calibration method reported by Van de Peer et al. (24).

TABLE 2.

GenBank accession numbers of the D1 and D2 sequences of a variety of yeast species and related fungi, used to estimate nucleotide substitution rates

| Phylum, class, and species | Accession no. | Phylum, class, and species | Accession no. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascomycota (n = 65) | ||||

| Archiascomycetes | ||||

| Schizosaccharomyces pombe | U40085 | |||

| Taphrina deformans | U94948 | |||

| Euascomycetes, Aureobasidium pullulans | AF050239 | |||

| Hemiascomycetes | ||||

| Arxula terrestris | U40103 | |||

| Blastobotrys nivea | U40110 | |||

| Candida bombi | U45706 | |||

| Candida cariosilignicola | U70188 | |||

| Candida caseinolytica | U70250 | |||

| Candida castellii | U69876 | |||

| Candida fennica | U45715 | |||

| Candida galacta | U45820 | |||

| Candida humilis | U69878 | |||

| Candida insectorum | U45791 | |||

| Candida nemodendra | U70246 | |||

| Candida norvegica | U62299 | |||

| Candida quercitrusa | U45831 | |||

| Candida quercuum | U70184 | |||

| Candida rugosa | U45727 | |||

| Candida sake | U45728 | |||

| Candida santjacobensis | U45811 | |||

| Candida shehatae | U45761 | |||

| Candida torresii | U45731 | |||

| Candida tropicalis | U45749 | |||

| Candida vini | U70247 | |||

| Clavispora lusitaniae | U44817 | |||

| Clavispora opuntiae | U44818 | |||

| Debaryomyces castellii | U45841 | |||

| Debaryomyces udenii | U45844 | |||

| Dekkera anomala | U84244 | |||

| Dipodascus albidus | U40081 | |||

| Dipodascus ingens | U40127 | |||

| Eremothecium coryli | U43390 | |||

| Galactomyces geotrichum | U40118 | |||

| Issatchenkia orientalis | U76347 | |||

| Issatchenkia terricola | U76345 | |||

| Kluyveromyces lodderae | U68551 | |||

| Kluyveromyces thermotolerans | U69581 | |||

| Lipomyces starkeyi | U45824 | |||

| Metschnikowia reukaufii | U44825 | |||

| Myxozyma mucilagina | U94945 | |||

| Myxozyma udenii | U76353 | |||

| Nadsonia commutata | U73598 | |||

| Pichia angophorae | U75521 | |||

| Pichia anomala | U74592 | |||

| Pichia cactophila | U75731 | |||

| Pichia euphorbiae | U73580 | |||

| Pichia farinosa | U45739 | |||

| Pichia inositovora | U45848 | |||

| Pichia japonica | U73579 | |||

| Pichia membranifaciens | U75725 | |||

| Pichia onychis | U75421 | |||

| Pichia opuntiae | U76203 | |||

| Pichia quercuum | U75416 | |||

| Pichia toletana | U75720 | |||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | U44806 | |||

| Saccharomycopsis capsularis | U40082 | |||

| Saturnispora dispora | U94937 | |||

| Stephanoascus smithiae | U76531 | |||

| Torulaspora delbrueckii | U72156 | |||

| Williopsis mucosa | U75961 | |||

| Williopsis salicorniae | U75968 | |||

| Yarrowia lipolytica | U40080 | |||

| Zygoascus hellenicus | U40125 | |||

| Zygosaccharomyces mellis | U72164 | |||

| Zygozyma smithiae | U84242 | |||

| Basidiomycota (n = 80) | ||||

| Hymenomycetes | ||||

| Agaricus arvensis | U11910 | |||

| Apiotrichum porosum | AF189833 | |||

| Auricularia auricula-judae | L20278 | |||

| Boletus rubinellus | L20279 | |||

| Bullera crocea | AF075508 | |||

| Bullera oryzae | AF075511 | |||

| Bulleromyces albus | AF075500 | |||

| Calocera cornea | AF291302 | |||

| Cryptococcus albidus | AF075474 | |||

| Cryptococcus curvatus | AF189834 | |||

| Cryptococcus diffluens | AF075502 | |||

| Cryptococcus gastricus | AF137600 | |||

| Cryptococcus heveanensis | AF075467 | |||

| Cryptococcus humicola | AF189836 | |||

| Cryptococcus laurentii | AF075469 | |||

| Cryptococcus magnus | AF181851 | |||

| Cryptococcus skinneri | AF189835 | |||

| Cryptococcus terreus | AF075479 | |||

| Cystofilobasidium capitatum | AF075465 | |||

| Fellomyces borneensis | AF189877 | |||

| Fellomyces fuzhouensis | AF075506 | |||

| Filobasidiella neoformans | AF075526 | |||

| Filobasidium capsuligenum | AF075501 | |||

| Ganoderma australe | X78780 | |||

| Mrakia frigida | AF075463 | |||

| Tremella aurantia | AF189842 | |||

| Tremella tropica | AF042251 | |||

| Trichosporon aquatile | AF075520 | |||

| Trichosporon montevideense | AF105397 | |||

| Trichosporon mucoides | AF075515 | |||

| Udeniomyces pyricola | AF075507 | |||

| Urediniomycetes | ||||

| Aurantiosporium subnitens | AF009846 | |||

| Bensingtonia phyllada | AF189894 | |||

| Eocronartium muscicola | L20280 | |||

| Erythrobasidium hasegawianum | AF189899 | |||

| Helicogloea variabilis | L20282 | |||

| Kondoa aerea | AF189901 | |||

| Kurtzmanomyces tardus | AF177410 | |||

| Leucosporidium felli | AF189907 | |||

| Leucosporidium scottii | AF070419 | |||

| Melampsora lini | L20283 | |||

| Occultifur externus | AF189909 | |||

| Pachnocybe ferruginea | L20284 | |||

| Rhodosporidium kratochvilovae | AF071436 | |||

| Rhodotorula aurantiaca | AF189921 | |||

| Rhodotorula bogoriensis | AF189923 | |||

| Rhodotorula ferulica | AF189927 | |||

| Rhodotorula fujisanensis | AF189928 | |||

| Rhodotorula glutinis | AF070430 | |||

| Rhodotorula hordea | AF189933 | |||

| Rhodotorula minuta | AF189945 | |||

| Rhodotorula vanillica | AF189970 | |||

| Sporidiobolus ruineniae | AF070438 | |||

| Sporidiobolus salmonicolor | AF070439 | |||

| Sporobolomyces coprosmae | AF189980 | |||

| Sporobolomyces coprosmicola | AF189981 | |||

| Sporobolomyces dracophylli | AF189982 | |||

| Sporobolomyces falcatus | AF075490 | |||

| Sporobolomyces gracilis | AF189985 | |||

| Sporobolomyces roseus | AF070441 | |||

| Sporobolomyces ruber | AF189992 | |||

| Sporobolomyces sasicola | AF177412 | |||

| Sporobolomyces singularis | AF189996 | |||

| Sporobolomyces tsugae | AF189998 | |||

| Sterigmatomyces elviae | AF177415 | |||

| Ustilaginomycetes | ||||

| Doassinga callitrichis | AF007525 | |||

| Entorrhiza aschersonia | AF009851 | |||

| Entyloma calendulae | AJ235296 | |||

| Exobasidium rhododendri | AF009856 | |||

| Malassezia furfur | AJ249955 | |||

| Melanotaenium endogenum | AJ235294 | |||

| Pseudozyma fusiformata | AJ235304 | |||

| Rhodotorula bacarum | AF190002 | |||

| Rhodotorula phylloplana | AF190004 | |||

| Thecaphora amaranthi | AF009873 | |||

| Tilletia caries | AJ235308 | |||

| Tilletiaria anomala | AJ235284 | |||

| Tilletiopsis flava | AJ235285 | |||

| Ustacystis waldsteiniae | AF009880 | |||

| Ustilago maydis | AJ235275 |

Comparison of 26S rRNA accessibilities in different yeasts.

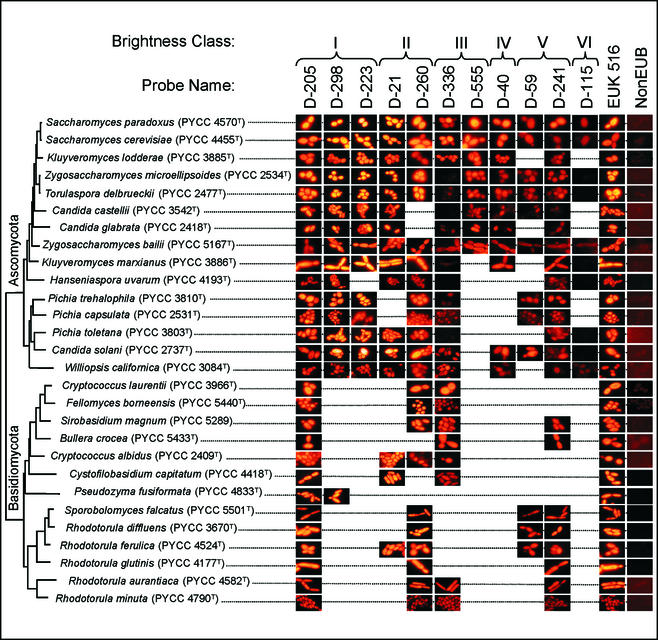

To evaluate whether the accessibility data obtained for the region analyzed in the S. cerevisiae 26S rRNA could be extrapolated to other yeast species, a subset of the probes tested in this study were used in FISH experiments with several yeast species that presented a full complementary target site for those probes. The probes and yeast species selected are shown in Fig. 2. The EUK 516 (5′-ACCAGACTTGCCCTCC) (2) and NonEUB (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGC) (25) probes were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. All of the yeast strains were grown, harvested, and paraformaldehyde fixed as described above. The FISH experiments were carried out as indicated above, and 10 μl of the final hybridization mixture was spotted onto microscopic slides, air dried in the dark, and mounted with Vectashield solution (Vector, Burlingame, Calif.). The slides were examined with an Olympus BX50 microscope fitted for epifluorescence microscopy with a U-ULH 100-W mercury high-pressure bulb and a U-MA1007 filter set for the fluorochrome Cy3 (Olympus). The fluorescence intensity of the hybridization signal was checked visually. Photomicrographs were obtained with a digital camera (Olympus C3030-ZOOM) and edited with standard software (Adobe Photoshop 6.0).

FIG. 2.

Comparison of in situ hybridization signals for S. cerevisiae and other yeast species. The probes selected fall into different accessibility classes in the S. cerevisiae 26S rRNA D1 and D2 domains and have an identical target site in that region for all of the yeasts indicated.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

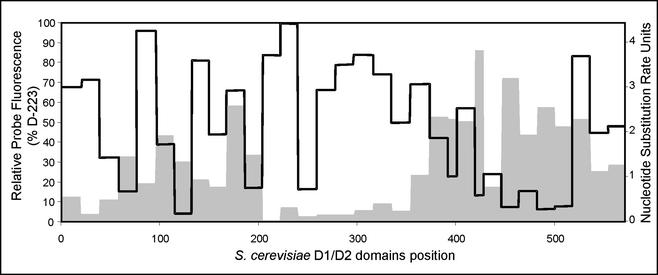

The results obtained for the in situ accessibility of S. cerevisiae 26S rRNA to Cy3-labeled oligonucleotide probes covering the full length of the D1 and D2 domains are shown in Fig. 1 and Table 1. Fluorescence intensities for each probe were quantified by flow cytometry, expressed as a percentage of the fluorescence signal of the brightest probe detected (D-223), and grouped into different accessibility classes (7). The fluorescence intensity obtained for probe D-223 was of the same order of magnitude as the signal shown by the universal eukaryote probe EUK 516, which is targeted to the 18S rRNA. About 44% of the probes tested belong to the higher-accessibility classes (I and II), and 28% were poorly binding (brightness classes V and VI). To evaluate whether the probes belonging to the most inaccessible classes (IV, V, and VI) would show better fluorescent signals under different hybridization conditions, a subset of these probes was chosen and hybridization reactions were performed at different temperatures. The use of hybridization conditions with different stringencies did not significantly improve the fluorescence intensities (data not shown), in accordance with previous studies (7). The overall results indicate that, despite its short length of approximately 600 nucleotides, the D1 and D2 domains include potentially good targets for yeast probe design. However, care should be taken when selecting target sites complementary to the most variable areas of the D1 and D2 domains (Fig. 3), where it is easier to find species-specific sequences. The data obtained show that the most conserved stretches of the studied region are more accessible (Fig. 3) (e.g., positions 200 to 350), and the most variable areas often show medium to low accessibility (e.g., the region between nucleotides 415 and 510). A similar trend has been observed in a previous accessibility study conducted for Escherichia coli 16S rRNA (7).

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the relative in situ accessibilities (black line) of the S. cerevisiae 26S rRNA D1 and D2 domains and the average nucleotide substitution rates (gray) in yeasts.

As for other probes belonging to the weaker accessibility classes (IV, V, and VI), whose low probe-conferred fluorescence signals may be due to the rRNA secondary structure and/or protein-rRNA interactions, the weaker signal of probe D-59 can additionally be attributed to a significant degree of self-complementarity in its sequence, an aspect to be taken into consideration when designing species-specific probes. Another possible explanation for the less intense fluorescence signals observed with some FISH probes is the quenching due to the presence of guanine residues adjacent to the 3′ ends of the rRNA targets (4, 22). We observed no significant correlation between the probe-conferred fluorescence intensities and this nucleobase position in the vicinity of the 3′ ends of the respective rRNA target sites (data not shown). This observation agrees with those of Torimura and colleagues (22), who observed the quenching phenomenon for fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled oligonucleotides but not for Cy3-labeled ones.

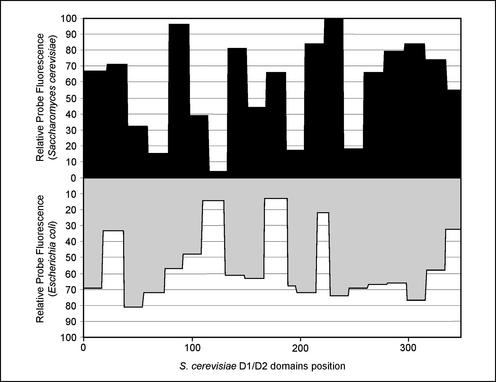

Interestingly, a comparative analysis of the in situ accessibility of the first 350 nucleotides in E. coli 23S rRNA to Cy3-labeled oligonucleotide probes (8) and the data obtained in this work for S. cerevisiae show some striking similarities (Fig. 4). Although the probes used have different target sequences in the two microorganisms, the accessibilities follow the same general trend. On the other hand, the probes belonging to the higher accessibility classes (I and II) in S. cerevisiae also yielded strong hybridization signals with species belonging to different phylogenetic groups, including the distantly related basidiomycetous yeasts (Fig. 2). This suggests that the D1-D2 accessibility map presented here for S. cerevisiae provides useful guidance for the design of species-specific probes for other yeasts, maybe even for other fungi or eukaryotic microorganisms. However, the design of probes for more distantly related organisms would probably require a different model.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of the accessibilities of homologous regions in S. cerevisiae 26S rRNA and E. coli 23S rRNA to Cy3-labeled probes.

With this study we hope to contribute to a more rational design of fluorescently labeled probes for yeast identification that will stimulate the use of FISH-based methods in a wide range of applications, including studies on the ecology of yeasts.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Max Planck Society, by a grant (Am73/3-1) from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to R.A., and by the Centro de Recursos Microbiológicos, New University of Lisbon. J.I. is supported by a Ph.D. grant (Praxis XXI/BD/19833/99) from Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, Portugal.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann, R., and W. Ludwig. 2000. Ribosomal RNA-targeted nucleic acid probes for studies in microbial ecology. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 24:555-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amann, R. I., B. J. Binder, R. J. Olson, S. W. Chisholm, R. Devereux, and D. A. Stahl. 1990. Combination of 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes with flow cytometry for analyzing mixed microbial populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:1919-1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amann, R. I., W. Ludwig, and K.-H. Schleifer. 1995. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol. Rev. 59:143-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crockett, A. O., and C. T. Wittwer. 2001. Fluorescein-labeled oligonucleotides for real-time PCR: using the inherent quenching of deoxyguanosine nucleotides. Anal. Biochem. 290:89-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fell, J. W., T. Boekhout, A. Fonseca, G. Scorzetti, and A. Statzell-Tallman. 2000. Biodiversity and systematics of basidiomycetous yeasts as determined by large-subunit rDNA D1/D2 domain sequence analysis. Int. J. Syst. E vol. Microbiol. 50:1351-1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuchs, B. M., F. O. Glöckner, J. Wulf, and R. Amann. 2000. Unlabeled helper oligonucleotides increase the in situ accessibility to 16S rRNA of fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide probes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3603-3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuchs, B. M., G. Wallner, W. Beisker, I. Schwippl, W. Ludwig, and R. Amann. 1998. Flow cytometric analysis of the in situ accessibility of Escherichia coli 16S rRNA for fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide probes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4973-4982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuchs, B. M., K. Syutsubo, W. Ludwig, and R. Amann. 2001. In situ accessibility of Escherichia coli 23S rRNA to fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide probes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:961-968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kempf, V. A. J., K. Trebesius, and I. B. Autenrieth. 2000. Fluorescent in situ hybridization allows rapid identification of microorganisms in blood cultures. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:830-838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kosse, D., H. Seiler, R. Amann, W. Ludwig, and S. Scherer. 1997. Identification of yoghurt-spoiling yeasts with 18S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 20:468-480. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurtzman, C. P., and C. J. Robnett. 1998. Identification and phylogeny of ascomycetous yeasts from analysis of nuclear large subunit (26S) ribosomal DNA partial sequences. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 73:331-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li, S., R. N. Spear, and J. H. Andrews. 1997. Quantitative fluorescence in situ hybridization of Aureobasidium pullulans on microscope slides and leaf surfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3261-3267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lischewski, A., M. Kretschmar, H. Hof, R. Amann, J. Hacker, and J. Morschhäuser. 1997. Detection and identification of Candida species in experimentally infected tissue and human blood by rRNA-specific fluorescent in situ hybridization. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2943-2948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lischewski, A., R. I. Amann, D. Harmsen, H. Merkert, J. Hacker, and J. Morschhäuser. 1996. Specific detection of Candida albicans and Candida tropicalis by fluorescent in situ hybridization with an 18S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probe. Microbiology 142:2731-2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moter, A., and U. B. Göbel. 2000. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for direct visualization of microorganisms. J. Microbiol. Methods 41:85-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliveira, K., G. Haase, C. Kurtzman, J. J. Hyldig-Nielsen, and H. Stender. 2001. Differentiation of Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis by fluorescent in situ hybridization with peptide nucleic acid probes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4138-4141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rice, J., M. A. Sleigh, P. H. Burkill, G. A. Tarran, C. D. O'Connor, and M. V. Zubkov. 1997. Flow cytometric analysis of characteristics of hybridization of species-specific fluorescent oligonucleotide probes to rRNA of marine nanoflagellates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:938-944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rigby, S., G. W. Procop, G. Haase, D. Wilson, G. Hall, C. Kurtzman, K. Oliveira, S. V. Oy, J. J. Hyldig-Nielsen, J. Coull, and H. Stender. 2002. Fluorescence in situ hybridization with peptide nucleic acid probes for rapid identification of Candida albicans directly from blood culture bottles. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2182-2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spear, R. N., S. Li, E. V. Nordheim, and J. H. Andrews. 1999. Quantitative imaging and statistical analysis of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) of Aureobasidium pullulans. J. Microbiol. Methods 35:101-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stender, H., C. Kurtzman, J. J. Hyldig-Nielsen, D. Sorensen, A. Broomer, K. Oliveira, H. Perry-O'Keefe, A. Sage, B. Young, and J. Coull. 2001. Identification of Dekkera bruxellensis (Brettanomyces) from wine by fluorescence in situ hybridization using peptide nucleic acid probes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:938-941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suggs, S. V., T. Hirose, T. Miyake, E. H. Kawashima, M. J. Johnson, K. Itakura, and R. B. Wallace. 1981. Use of synthetic oligodeoxyribonucleotides for the isolation of specific cloned DNA sequences, p. 683-693. In D. Brown and C. F. Fox (ed.), Developmental biology using purified genes. Academic Press, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 22.Torimura, M., S. Kurata, K. Yamada, T. Yokomaku, Y. Kamagata, T. Kanagawa, and R. Kurane. 2001. Fluorescence-quenching phenomenon by photoinduced electron transfer between a fluorescent dye and a nucleotide base. Anal. Sci. 17:155-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van de Peer, Y., and De Wachter. 1994. TREECON for Windows: a software package for the construction and drawing of evolutionary trees for the Microsoft Windows environment. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 10:569-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van de Peer, Y., G. Van der Auwera, and R. De Wachter. 1996. The evolution of Stramenopiles and Alveolates as derived by substitution rate calibration of small ribosomal subunit RNA. J. Mol. Evol. 42:201-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wallner, G., R. Amann, and W. Beisker. 1993. Optimizing fluorescent in situ hybridization with rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes for flow cytometric identification of microorganisms. Cytometry 14:136-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]