Abstract

Background

Many different wound dressings and topical applications are used to cover surgical wounds healing by secondary intention. It is not known whether these dressings heal wounds at different rates.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of dressings and topical agents on surgical wounds healing by secondary intention

Search methods

We sought relevant trials from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Trials Register, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL databases in March 2002.

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the effectiveness of dressings and topical agents for surgical wounds healing by secondary intention.

Data collection and analysis

Eligibility for inclusion was confirmed by two reviewers who independently judged the methodological quality of the trials according to the Dutch Cochrane Centre list of factors relating to internal and external validity. Two reviewers summarised data from eligible studies using a data extraction sheet, any disagreements were referred to a third reviewer.

Main results

Fourteen reports of 13 RCTs on dressings or topical agents for postoperative wounds healing by secondary intention were identified.

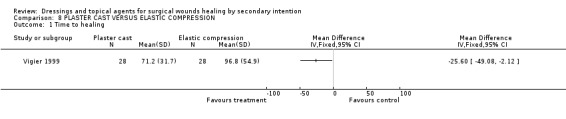

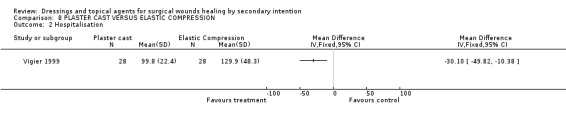

WOUND HEALING: Whilst a single small trial of aloe vera supplementation vs gauze suggests delayed healing with aloe vera, the results of this trial are un interpretable since there was a large differential loss to follow up. A plaster cast applied to an amputation stump accelerated wound healing compared with elastic compression, WMD ‐25.60 days, 95% CI ‐49.08 to ‐2.12 days (1 trial). There were no statistically significant differences in healing for other dressing comparisons (e.g. gauze, foam, alginate; 11 trials). PAIN: Gauze was associated with significantly more pain for patients than other dressings (4 trials). PATIENT SATISFACTION: Patients treated with gauze were less satisfied compared with those receiving alternative dressings (3 trials). COSTS: Gauze is inexpensive but its use is associated with the use of significantly more nursing time than foam (2 trials). LENGTH OF HOSPITAL STAY: Four trials showed no difference in length of hospital stay. One trial found shorter hospital stay in people after amputation when plaster casts were applied compared with elastic compression (WMD ‐30.10 days; 95% CI ‐49.82 to ‐10.38).

Authors' conclusions

We found only small, poor quality trials; the evidence is therefore insufficient to determine whether the choice of dressing or topical agent affects the healing of surgical wounds healing by secondary intention. Foam is best studied as an alternative for gauze and appears to be preferable as to pain reduction, patient satisfaction and nursing time.

Keywords: Humans; Bandages; Surgical Procedures, Operative; Wound Healing; Occlusive Dressings; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Dressings and topical agents to help surgical wounds heal by secondary intention

Most surgical incisions heal by primary intention, i.e. the edges of the surgical incision are closed together with stitches or clips until the cut edges merge. Healing by secondary intention refers to healing of an open wound, from the base upwards, by laying down new tissue. There are many kinds of dressings and topical agents available but few have been evaluated in trials. This review did not find any evidence that any one dressing or topical agent speeds up the healing of surgical wounds healing by secondary intention more than another, although gauze may be associated with greater pain or discomfort for the patient.

Background

Most surgical incisions heal by primary intention, i.e. the edges of the surgical incision are closed together with stitches or clips until the cut edges merge. Healing by secondary intention refers to healing of an open wound, from the base upwards, by deposition of new tissue. The prevalence of surgical wounds healing by secondary intention is unknown. Delayed healing by secondary intention may be planned, for example when wounds are contaminated or at high risk of infection. This occurs when surgery involves body cavities containing infected, necrotic or contaminated tissue, for example in colorectal surgery, where the usual post‐surgical infection rate is 10 to 30% (McLaws 2000). Concurrent infection is a known risk factor for abdominal wound dehiscence (where the edges of the surgically closed wound split apart, leaving an open wound) (Graham 1998). Where infection is present within a closed wound, surgeons may remove sutures or clips in order to allow free drainage of exudate. The wound then heals by secondary intention.

It is generally accepted that factors like infection, poor physiological status (Hall 1996, Desai 1997) and/or nutritional status (Correia 2001, Keithley 1985) are associated with higher surgical complication rates and mortality and an increased probability of unintended delay in wound healing. Other determinants of whether wounds are likely to heal by secondary intention are location and depth of the wound, characteristics of the surrounding skin and completeness of tumour excision (Bernstein 1989).

It is believed that postoperative wounds healing by secondary intention require local care e.g. maintenance of a moist wound environment. There are many kinds of dressings (e.g. gauze, bandages etc.) and topical agents (locally applied drugs; e.g. antiseptics, enzymes, etc.) available for local wound management. The ideal dressing for healing wounds by secondary intention probably has several attributes including the ability of the dressing to absorb and contain exudate without leakage, the impermeability of the dressing to water and bacteria, the lack of particulate contaminants left in the wound by the dressing and the avoidance of wound trauma on dressing removal (Sharp 2002). Poorly healing surgical wounds are also often treated with topical agents such as hydrogels and topical antimicrobials (Gruessner 2001, Giele 2001, Brockenbrough 1969). The choice of dressings and topical agents for these kinds of wounds is not always based on a firm rationale (Lewis 2001). This review aims to identify and summarise the evidence for the effectiveness of different dressings and topical agents (outlined below) in the management of surgical wounds healing by secondary intention, irrespective of whether the secondary intention was planned or unplanned.

The British National Formulary has classified dressings into categories to aid clinicians in selecting appropriate products (BNF 2003). This review uses the same categories to organise the material.

Wound dressing pads. This group of dressings includes knitted viscose and gauze dressings. They are usually in the form of woven or knitted pads that are applied directly to the wound surface. In this review we use the term 'gauze' for dressings in this category.

Tulle dressings. These can be either non‐medicated (e.g. paraffin gauze dressing) or medicated (e.g. containing povidone‐iodine or chlorhexidine).

Semi‐permeable film dressing. These dressings are in the form of transparent films. They are semi‐permeable and allow some gaseous exchange but are impervious to bacteria (DTB 1991).

Hydrocolloid dressings. These occlusive dressings contain a hydrocolloid matrix with elastomeric and adhesive substances attached to a polymer base (Cullum 1994). On contact with wound exudates the hydrocolloid liquefies, producing a moist environment for wound healing to take place (Smith 1994). The dressing seals the wound and is impervious to gas, bacteria and liquid. They can be left in place for up to seven days.

Hydrogel dressings. These consist of a starch polymer and up to 80% water. They have the ability to absorb wound exudates or rehydrate a wound depending on their composition and whether the wound is moist and sloughy or dry and necrotic.

Alginate dressings. These are also included in the hydrogel group. These dressings are derived from seaweed and are in the form of a loose fibrous rope or pad. The calcium ions in the dressing interact with sodium ions within wound exudates to produce a fibrous gel. The gel is thought to provide a moist wound environment that allows gaseous exchange and a barrier to contamination (McMullen 1991).

Bead dressings. These dressings absorb exudates, wound debris, and microorganisms by capillary action either into the beads or into the matrix between the beads. They require a secondary dressing to maintain them in place.

Foam dressings. These are either in the form of sheets or can be applied as a liquid that expands to fill the wound cavity.

In addition there are a number of topical agents, which aim to change the wound‐environment.

Topical antibiotics, examples are neomycin, bacitracin, polymyxin B, gentamycin, fusidic acid, mupirocin, and quinolones.

Topical antiseptics, examples are hexachlorophene, povidone‐iodine and chlorhexidine.

Topical steroid preparations.

Topical steroid/antibiotic combination.

Topical oestrogen.

Topical enzymatic agents.

Topical growth factors.

Topical collagen.

Other topical preparations.

Objectives

To summarise the evidence for the effects of dressings and topical agents on the healing of surgical wounds healing by secondary intention. We considered comparisons between:

dressings versus dressings

dressings versus topical agents

dressings versus no dressings

topical agents versus topical agents

topical agents versus no topical agents

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the effects of dressings or topical agents for surgical wounds healing by secondary intention. We decided a priori, that non randomised studies would only be included in the absence of RCTs, due to their susceptibility to bias.

Trials were included if the following criteria applied:

the allocation of patients was described as randomised or it was evident that the interventions were assigned at random.

the trial sample included patients with surgical wounds healing by secondary intention.

a dressing and/or a topical agent was used.

Types of participants

Men and women aged 18 years and over with surgical wounds healing by secondary intention. The review excludes skin graft donor sites, as they form a specific group of superficial wounds, which require specific care.

Types of interventions

We considered comparisons between any dressing or topical agent applied to surgical wounds healing by secondary intention:

dressings versus dressings

dressings versus topical agents

dressings versus no dressings

topical agents versus topical agents

topical agents versus no topical agents.

Types of outcome measures

In order to be included in the review a trial report had to provide at least one of the primary outcomes.

Primary outcomes

Wound healing objectively measured by: (a) Time to complete wound healing / proportion of wounds completely healed in a specified time period. The complete healing of wounds is a definitive endpoint, because it can be measured objectively, and is likely to be the outcome of greatest interest to patients. (b) Change in wound area surface over time/ proportion of wounds partly healed in a specified time period. (There is no consensus about the most valid and reliable means of measuring healing rates of wounds.)

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcome measures according to the scales used in the various articles: (a) Pain (b) Exudate (c) Complications and morbidity (d) Patient satisfaction (e) Quality of life data, generic or specific measures of quality of life

Economic evaluation outcome: (a) Costs of the dressings and topical agents (b) Cost‐effectiveness or cost‐benefit analysis (c) Hospitalisation period

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Wounds Group Specialised Trials Register and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials was last searched in March 2002 using the following strategy:

1. BANDAGES explode all trees (MeSH) 2. OINTMENTS explode tree 1 (MeSH) 3. ANTI‐INFECTIVE AGENTS LOCAL explode tree 1 (MeSH) 4. ADMINISTRATION CUTANEOUS explode tree 1 (MeSH) 5. ANTI‐INFECTIVE AGENTS QUINOLONE explode tree 1 (MeSH) 6. GLUCOCORTICOIDS TOPICAL explode tree 1 (MeSH) 7. (dressing* or bandag* or stocking* or wrap* or gauze*) 8. (ointment* or lotion* or cream* or foam or silver or carbonated or film) 9. ((compression next therapy) or (topical next agent*)) 10. (hydrocolloid* or alginat* or hydrogel* or quinolone*) 11. COLLAGENASES explode tree 1 (MeSH) 12. (#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5) 13. (#6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11) 14. (#12 or #13) 15. SURGICAL WOUND INFECTION explode tree 1 (MeSH) 16. SURGICAL WOUND DEHISCENCE explode tree 1 (MeSH) 17. ((surgical near wound*) or (surgical near incision*) or (surgical near site* near infection*)) 18. (#15 or #16 or #17) 19. (#14 and #18)

Silver Platter MEDLINE(R), CINAHL and EMBASE was searched in March 2002 using the following strategy:

#1 surg* or postop* #2 delay* or second* or compli* #3 wound* and heal* #4 topical* #5 antibio* or antisep* or steroid* or estrogen* or enzym* or grow* or collagen* #6 (topical*) and (antibio* or antisep* or steroid* or estrogen* or enzym* or grow* or collagen*) #7 (surg* or postop*) and (delay* or second* or compli*) and (wound* and heal*) #8 ((topical*) and (antibio* or antisep* or steroid* orestrogen* or enzym* or grow* or collagen*)) and ((surg* or postop*) and (delay* or second* or compli*) and (wound* and heal*)) #9 random* or controlled* or single‐blind* or double‐blind* or review* #10 dressing* or bandage* or gauze* or tulle* or film* or hydrocol* or hydrogel* or alginat* or bead* or foam* #11 (((topical*) and (antibio* or antisep* or steroid* or estrogen* or enzym* or grow* or collagen*)) and ((surg* or postop*) and (delay* or second* or compli*) and (wound* and heal*))) and (random* or controlled* or single‐blind* or double‐blind* or review*) #12 ((surg* or postop*) and (delay* or second* or compli*) and (wound* and heal*)) and (dressing* or bandage* or gauze* or tulle* or film* or hydrocol* or hydrogel* or alginat* or bead* or foam*) #13 (random* or controlled* or single‐blind* or double‐blind* or review*) and (((surg* or postop*) and (delay* or second* or compli*) and (wound* and heal*)) and (dressing* or bandage* or gauze* or tulle* or film* or hydrocol* or hydrogel* or alginat* or bead* or foam*))

Searching other resources

We did not limit the search by language or publication status. We searched citations within identified studies. We did not write to manufacturers and distributors of wound dressings for details of unpublished or ongoing trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two reviewers (HV and AG) independently screened the titles and abstracts of references identified by the search for potential relevance and design. In case of disagreement or doubt a third reviewer was consulted (DU). From this initial assessment on title and abstract, we obtained full versions of all potentially relevant articles. HV and AG independently checked the full papers to identify those that met the inclusion criteria. Again, disagreement was resolved by discussion and if necessary a third reviewer was consulted (DU).

Data extraction and management

We extracted the details of the RCTs and summarised these by using a data extraction sheet (Dutch Quality Institute for Health Care Improvement / Dutch Cochrane Centre) (www.cochrane.nl). We included trials published in duplicate only once. HV and AG independently undertook data extraction. Any disagreement was referred to DU for adjudication.

The following data were extracted:

Characteristics of the trial (design, method of randomisation)

Trial participants (number, co‐interventions, setting)

Intervention (dressing, topical agent, nothing)

Comparison intervention (dressing, topical agent, nothing)

Outcome measures, primary (time to complete healing, wound area volume, proportion of wounds healed within trial period)

Outcome measures, secondary (pain, complications, patient satisfaction, quality of life, cost of local treatment and hospitalisation time)

Results

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The methodological quality of each trial was assessed systematically according to the Dutch Quality Institute for Health Care Improvement / Dutch Cochrane Centre on factors relating to internal and external validity (www.cochrane.nl). These criteria include:

Was allocation of intervention randomised?

Was allocation concealed for the researcher who included the patients?

Was the proportion of completed follow up > 80%?

Was an intention to treat analysis used?

Were all patients blinded for the intervention?

Were all health care workers blinded for the intervention?

Were all outcome assessors blinded for the intervention?

Were both groups comparable at baseline?

Were both groups, apart from the investigated intervention, treated the same?

Are the results of this trial valid and applicable?

Was the sample size based on a proper a priori calculation?

Two reviewers performed the quality assessment of each study independently and any disagreement was referred to DU for adjudication.

Data synthesis

Quantitative data were entered into the Cochrane RevMan 4.2 software and analysed with Cochrane MetaView. For each outcome, summary estimates of treatment effect (with 95% confidence intervals (CI)) were calculated for every comparison. For continuous outcomes the weighted mean differences (WMD) or standardised mean differences (SMD) were presented when appropriate. For dichotomous outcomes relative risk (RR) was presented when appropriate. We refrained from a sensitivity analysis, because of the small number of trials.

We grouped trials according to the type of intervention, i.e. dressing (BNF 2003) or topical agent. We combined results of clinically homogeneous trials (trials for which the participants, interventions, outcome measures and timing of the follow‐up measurements were considered sufficiently similar) using a fixed effects model. A random effects model was used in the presence of statistical heterogeneity (assessed by visual inspection of the forest plots and chi‐square test for heterogeneity) but where trials were otherwise regarded as sufficiently similar. Where trials were regarded as clinically or methodologically heterogeneous, pooling was not performed.

Results

Description of studies

The search identified 581 titles of which 242 were possibly relevant and their abstracts were obtained. Two reviewers (HV and AG) independently read the abstracts and applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria (e.g. no RCT, no secondary healing, no surgical wound, no primary outcome). Referral was made to DU regarding one study, in which a systemic treatment was used. Fourteen reports on 13 RCTs were identified as having met the inclusion criteria (see Characteristics of Included Studies Table). The Characteristics of Excluded Studies Table summarises the studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded from the review.

All trials were published between 1980 and 2000. Study sizes ranged from 20 to 80 patients and nearly 600 patients were included in the studies. Six trials recruited patients with pilonidal sinuses after incision or excision; five trials described patients with postoperative wound breakdown; one trial studied patients with perineal wounds after excision of the rectum, and one trial included patients with below knee amputation wounds.

Each trial represented a unique comparison and various outcomes were reported; a foam dressing was evaluated in seven trials; an alginate in three; gauze ‐with or without a topical agent‐ in ten trials; a bead dressing in one trial; hydrocolloids in one trial; one evaluated a plaster cast and one Aloe Vera gel. Two out of 13 trials had three treatment arms.

All included trials measured wound healing, except for the one cost‐benefit trial (Culyer 1983), which was an economic analysis of the data from Macfie 1980. Pain was measured in different ways. No trials measured quality of life, but six trials measured patient satisfaction. Costs were measured in four trials and hospital stay in five.

Risk of bias in included studies

In all 13 trials the authors stated that allocation was random e.g. sealed envelopes, drawn lots, but the method of generating the randomisation sequence was not always clear. Consequently, the extent to which allocation was concealed was also unclear in 12 trials. Only in one trial (Schmidt 1991) was the allocation concealment adequate. In nine of the 13 trials, the proportion of people who completed follow‐up was >80% and an intention to treat analysis was used. Blinding was poorly reported, and whilst it is very difficult to blind patients and health care workers to the intervention it should be possible to blind outcome assessors. In two trials (Cannova 1998 a vs c; Goode 1979) the outcome assessors were blinded to the intervention. In eight trials both groups were comparable at baseline, and eight trials avoided co‐interventions. No trial reported a priori sample size calculation. Sample size, range 20 to 80 tended to be small.

We have appraised the quality of each trial using the quality list of the Dutch Quality Institute for Health Care Improvement / Dutch Cochrane Centre and have put this information in the Additional Tables. We did not perform a sensitivity analysis to look at the effect of validity issues because of the small number of trials.

See Additional Tables (Table 1; Table 2) for individual quality scores.

1. Quality 1.

| study | interv alloc random | allocation concealed | follow up > 80% | ITT analysis | patient blind to int | care workers blind | o/c assessor blind | gps comp baseline | gps treated same |

| Berry 1996 | yes | not clear | no | yes | not clear | no | no | no | yes |

| Cannova 1998 | yes | yes | yes | yes | not clear | not clear | yes | no | not clear |

| Eldrup 1985 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | no | not clear | not clear | not clear |

| Goode 1979 | yes | not clear | yes | yes | not clear | not clear | yes | yes | yes |

| Guillotreau 1996 | yes | not clear | not clear | not clear | not clear | not clear | not clear | not clear | not clear |

| Macfie 1980 | yes | not clear | yes | yes | not clear | no | no | yes | yes |

| Meyer 1997 | yes | not clear | not clear | yes | not clear | not clear | not clear | yes | not clear |

| Schmidt 1991 | yes | yes | no | not clear | no | no | no | yes | yes |

| Viciano 2000 | yes | not clear | yes | yes | no | no | no | yes | yes |

| Vigier 1999 | yes | not clear | yes | yes | not clear | not clear | not clear | yes | yes |

| Walker 1991 | yes | not clear | yes | not clear | not clear | no | not clear | yes | yes |

| Williams 1981 | yes | not clear | yes | yes | not clear | not clear | not clear | not clear | not clear |

| Young 1982 | yes | not clear | yes | yes | not clear | not clear | not clear | yes | yes |

2. Quality 2.

| Study | results valid/applic | apriori samp size ca |

| Berry 1996 | yes | no |

| Cannova 1998 | yes | no |

| Eldrup 1998 | yes | no |

| Goode 1979 | yes | no |

| Guillotreau 1996 | yes | no |

| Macfie 1980 | yes | no |

| Meyer 1997 | yes | no |

| Schmidt 1991 | yes | no |

| Viciano 2000 | yes | no |

| Vigier 1999 | yes | no |

| Walker 1991 | yes | no |

| Williams 1981 | yes | no |

| Young 1982 | yes | no |

Effects of interventions

Of the 13 included trials, none compared the same interventions and reported the same outcomes. Only trials which compared dressings versus dressings and dressings versus another dressing plus a topical agent were identified. We found no trials for the other comparisons. Ten trials compared gauze with another dressing, but there was substantial heterogeneity in terms of wound types, different forms of gauze dressings, and different comparison dressings, so that pooling was frequently inappropriate.

Results are presented for each dressing comparison (eight comparisons) and primary, secondary and economic outcomes are presented when reported.

We identified one trial that compared a plaster cast with a compression bandage for people who had undergone below the knee amputation. The study evaluated the effect of gauze moistened with calcium oxide. We therefore included it in the comparisons.

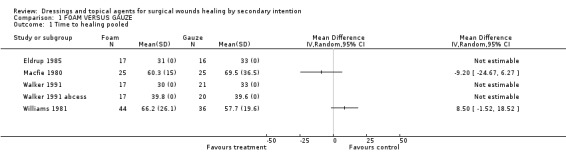

Comparison 01: FOAM VERSUS GAUZE (5 trials)

Five trials compared foam with gauze; four of these used antiseptic impregnated gauze (Eldrup 1985; Macfie 1980; Walker 1991; Williams 1981), one used gauze moistened with an unreported solution (Meyer 1997). Eldrup 1985 randomised 33 patients with open therapy after pilonidal sinus excision to either silastic foam dressing or gauze soaked with choramine. Macfie 1980 (+Culyer 1984 economic data) randomised 50 patients with open perineal wounds after abdominal perineal excision of the rectum to either silicone foam elastomer or ribbon gauze soaked in mercuric chloride antiseptic solution. Meyer 1997 randomised 43 patients with laparotomy or surgical incision of an abscess to either polyurethane foam containing hydroactive particles or cotton gauze soaked with an unreported solution and covered by a simple surgical dressing. Walker 1991 randomised 75 patients with open excision of pilonidal sinus and abscesses to either silicone foam cavity dressing or Eusol‐soaked gauze at half strength. Williams 1981 randomised 80 patients with excision of a pilonidal sinus to either silastic foam cavity dressing or gauze soaked in 0.5% aqueous solution of chlorhexidine.

1. Primary outcome measure: wound healing.

Four out of five trials reported time to complete healing (Eldrup 1985; Macfie 1980; Walker 1991; Williams 1981), whilst one reported proportion of participants completely healed at 4 weeks (Meyer 1997).

Time to healing

Walker 1991 studied 2 patient groups; those undergoing excision of a pilonidal abscess and those with pilonidal sinuses. We have plotted these patient groups separately. Two of the remaining trials (Eldrup 1985; Williams 1981) also studied people with pilonidal abscesses, whilst Macfie 1980 studied people with perineal wounds after abdominoperineal excision of rectum. None of the trials showed a statistically significant difference in time to healing between foam and gauze (Graph: Comparison 1, Outcome 1). Pooling of any of these studies was inappropriate as the wound types studied were heterogeneous, as were the comparison interventions (particularly in terms of antiseptic solution). All of these trials were small and we could not be confident that any of them had blinded assessment of outcomes.

Proportion of wounds completely healed

Meyer 1997 reported reduction in wound size and proportion of wounds healed completely at 4 weeks. Whilst more wounds were completely healed in the foam group at 4 weeks compared with gauze, this difference was not statistically significant (RR 2.62, 95% CI 0.97 ‐ 7.07). The difference in reduction in wound size at 4 weeks was not significantly different: 76% for foam and 50% for gauze.

2. Secondary outcome measures: pain, patient satisfaction and quality of life according to the scales used in the various articles.

(a) Pain Two studies (Macfie 1980; Meyer 1997) reported patients' levels of pain but in different ways. Macfie 1980 recorded the number of times analgesia was given (intramuscular preparations and Entonox, as well as oral preparations). Significantly fewer people in the foam group required analgesia compared with the gauze group (4/25 (16%), for foam versus 15/25 (60%) for gauze, RR 0.27 (95%CI 0.10 to 0.69). Meyer 1997 measured pain at week 4 using a 10‐point visual analogue scale (higher score indicating more pain) and reported a small but statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) indicating more pain with the gauze dressing (mean score 1.82) compared with foam (0.86). Meyer did not report variance data, so we could not calculate a 95% CI.

(b) Exudate ‐ None of the studies reported volume or type of exudate.

(c) Complications and morbidity Complications and morbidity were reported in two trials. Macfie 1980 reported one adverse event in a patient who underwent proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis and received foam treatment. An elastomer stent was fashioned in the usual way and the patient was discharged from the hospital uneventfully. On review in the clinic two months postoperatively she complained of severe vaginal odour and, on examination, a piece of foam stent was discovered lying high in the vault of the vagina, which was removed under a general anaesthetic. Meyer (1997) reported that no cases of necrotic tissue, odour, putrid secretion and/or itching were observed during the study.

(d) Patient satisfaction Two trials measured patient satisfaction, but in different ways. Williams 1981 reported discomfort experienced when the dressing was changed during the first week. The degree of discomfort was obtained by dividing the total score for that week by the number of dressing changes undertaken; extreme (3), moderate (2), mild (1), none (0). The average discomfort experienced was significantly lower in the foam group was (1.4 ± 0.6, versus 2.9 ± 2.6 in the gauze group; WMD 1.5, 95%CI 0.63 to 2.37). The clinical relevance of a 1.5 change in the discomfort score is not clear. Eldrup (1985) stated that the foam dressing was more comfortable to patients but reported no data.

(e) Quality of life data. No studies reported health‐related quality of life.

3. Economic evaluation outcome

One of the included studies incorporated a cost‐effectiveness study (Macfie 1980).

(a) Costs of the dressings and topical agents Culyer 1983 reports cost per case, (materials and non‐materials). This data is reported in Table 3; Foam vs. gauze: costs; material, other and total. Culyer (1983) concluded that the foam dressing was less costly both in terms of materials and of nursing time. Pure dressing costs for foam were higher but the non‐material costs were lower. The total costs per case demonstrated that foam is less expensive. No statistical calculation was performed to compare both groups.

3. Foam vs gauze: costs; material, other and total.

| Foam | Gauze | Difference | ||

| Costs of materials | ||||

| Low | 49.60 | 65.10 | ‐ 15.50 | |

| Medium | 81.30 | 121.60 | ‐ 40.30 | |

| High | 115.60 | 178.90 | ‐ 63.30 | |

| Other costs | ||||

| Low | 20.90 | 81.00 | ‐ 60.1 | |

| Medium | 80.80 | 296.00 | ‐ 215.2 | |

| High | 306.40 | 805.50 | ‐ 499.1 | |

| Total | ||||

| Low | 70.50 | 146.10 | ‐ 75.6 | |

| Medium | 162.10 | 417.60 | ‐ 255.5 | |

| High | 422.00 | 984.40 | ‐ 562.4 |

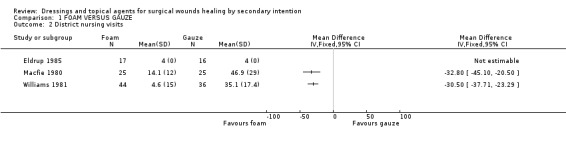

(b) Cost‐effectiveness or cost‐benefit analysis No real cost‐effectiveness calculations were made in the trials but cost aspects like district nursing visits or cost for these visits were mentioned in four trials (Williams 1981, Eldrup 1985; Macfie 1980, Culyer 1983). Williams 1981 reported time lost from work: 38.6 days for foam versus 45.4 days for gauze, with fewer home nursing visits for foam (4.6 visits versus 35.1 for gauze). Macfie 1980 also reported that the number of home visits was fewer for foam at 14.1 compared with 46.9 for gauze. The difference was statistically significant in favour of foam for both studies (Graph: Comparison 1, Outcome 2). Eldrup 1985 reports no difference between the number of home nursing visits (4 visits in both groups) but did not provide costs in the same way for both groups (i.e. total as for foam or per day as for gauze) therefore it is difficult to interpret this data. Culyer (1983) calculated the cost of district nursing time rather than reporting the number of visits. For the foam group it was divided in transport and time costs, for the gauze group not. The data is given in Table 4: Foam vs. gauze: costs; district nursing

4. Foam vs gauze: costs; district nursing.

| Foam | Gauze | Difference | ||

| District nursing costs | ||||

| Low | 4.37 | 54.72 | ‐ 50.35 | |

| Medium | 37.37 | 196.98 | ‐159.61 | |

| High | 138.57 | 455.40 | ‐316.83 |

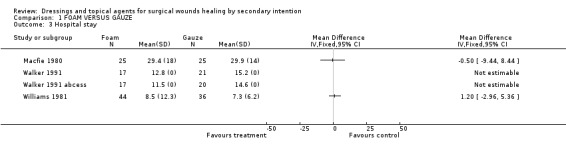

(c) Hospitalisation period The hospitalisation period was reported in three trials; MacFie, Walker and Williams. MacFie reported days in terms of inpatient stay plus convalescence. There was no difference between the groups with foam at 29.5 days and gauze at 29.9 days. Williams reported duration of hospital stay (8.5 days for foam compared with 7.3 days for gauze). There was a trend towards longer hospital stay associated with gauze in the Walker study for patients with either pilonidal sinuses or pilonidal abscess (pilonidal sinuses: average length of stay in foam group was 12.8 days versus 15.2 days for gauze, pilonidal abscess: average length of stay was 11.5 days for foam compared to 14.6 days for gauze). These differences were not statistically significant (Graph: Comparison 1, Outcome 3).

Summary

There is a small number of underpowered, poor quality studies with little replication. There is no clear evidence of a difference between gauze and foam in terms of healing. Patients may experience less pain and require fewer nursing visits with foam.

Comparison 02: BEAD VERSUS GAUZE (1 trial)

Goode 1979 compared dextranomer with Eusol soaked ribbon gauze in a small trial with 10 patients in each group. Patients had open, infected surgical wounds after appendectomy or bowel surgery

1. Primary outcome measure; wound healing

There was no significant difference between dextranomer and Eusol gauze in terms of number of wounds healing without secondary closure (only 1 healed in each group).

2. Secondary outcome measures include pain, patient satisfaction and quality of life according to the scales used in the various articles

(a) Pain ‐ Not reported. (b) Exudate ‐ Not reported. (c) Complications and morbidity ‐ Not reported. (d) Patient satisfaction ‐ Not reported. (e) Quality of life data, generic or specific measures of quality of life ‐ Not reported.

3. Economic evaluation outcome

(a) Costs of the dressings and topical agents ‐ Not reported

(b) Cost‐effectiveness or cost‐benefit analysis Goode commented that bead dressings were more expensive than gauze but this was compensated for by shorter hospital stay but this statement was not built on data.

(c) Hospitalisation period Goode 1979 reported that the patients treated with bead dressing had a shorter hospital stay by a median of 2.2 days. No data or statistics are given.

Summary

There is insufficient evidence from one trial on the comparative effects of dextranomer bead dressing and Eusol soaked gauze, for wounds healing by secondary intention.

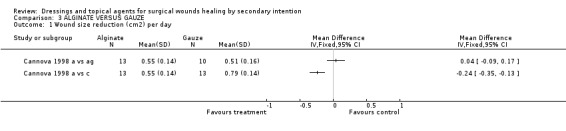

Comparison 03: ALGINATE VERSUS GAUZE (2 trials)

Two trials compared alginate and gauze dressings.

Cannova (1998) compared alginate [n=13] with sodium hypochlorite moistened gauze [n=10] with a combined dressing pad [n=13] in patients with surgical abdominal wounds.

Guillotreau 1996 compared calcium alginate rope [n=37] with povidone iodine packing soaked gauze [n=33] in patients with incision and drainage of pilonidal abscess.

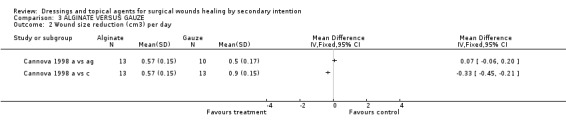

1. Primary outcome measure; wound healing

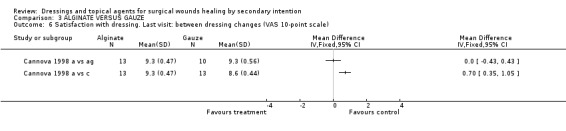

Both trials reported wound healing, but in different ways. Cannova's trial (1998) had three study arms. Patients were randomised to alginate, antiseptic gauze or the combined dressing pad. Wound healing was expressed in cm²/day and cm³/day, and for both, the % change was calculated. There were no significant differences in healing rates between alginate and either of the gauze comparators, though the average healing rate in the combined dressing pad group tended to be higher. Graph: Comparison 3, Outcome 1 and 2.

In the trial by Guillotreau 1996, healing was reported as proportion of wounds completely healed during a 3‐week follow‐up period. 13 out of 37 wounds in the alginate group (35%) compared with 6 of 33 (18%) wounds in the gauze group were healed at 3 weeks; this difference was not statistically significant (RR 1.93: 95%CI; 0.83 to 4.50. The trial is small and therefore underpowered to detect clinically important differences.

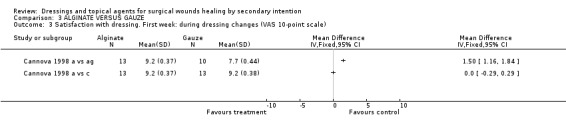

2. Secondary outcome measures include pain, patient satisfaction and quality of life according to the scales used in the various articles.

(a) Pain Both trials studied pain with a 10‐point VAS scale. Cannova (1998) measured pain, 30 to 60 minutes after the first dressing change of the day and subsequently at weekly intervals. Only the maximum pain score is reported. Calcium alginate caused significantly less pain (mean score 2.5 ± 0.65 on 10‐point VAS scale) than antiseptic gauze (mean score 5.2 ± 0.74, WMD ‐2.7 CI ‐3.28 to ‐2.12), but did not differ much from the maximum pain in the combined dressing pad group (mean score 2.9 ± 0.65, WMD ‐0.40 CI ‐0.90 to 0.10). Guillotreau 1996 also used a visual analogue scale and reported that alginate rope was painless (p=0.0001) compared to gauze, but no group data were given.

(b) Exudate ‐ Not reported

(c) Complications and morbidity In the alginate group of Cannova's trial (1998) one wound developed a sinus after three weeks, requiring further surgery and another wound showed over‐granulation after three weeks. In the antiseptic gauze group two patients developed a sinus after two weeks, of which one required further surgery.

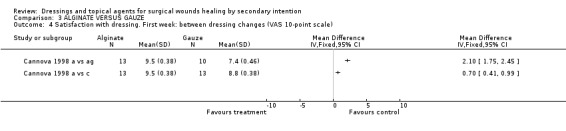

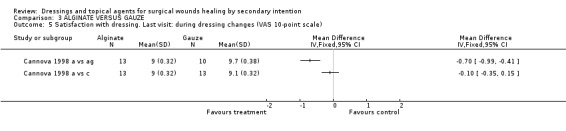

(d) Patient satisfaction Cannova et al (1998) assessed patient comfort using a questionnaire with a 10 point rating scale during dressing changes and between dressing changes in the first week and at the last visit. Patients in the antiseptic gauze group were significantly less satisfied than those in the alginate group, Graph: Comparison 3, outcome 3. No differences were found for the comparison alginate versus combined dressing pad, Graph: Comparison 3, outcome 4,5,6. The large number of comparisons means there is a high likelihood of a type 1 error. Guillotreau 1996 mentioned that alginate rope was easier to use (p=0.011). No data are given.

(e) Quality of life data, generic or specific measures of quality of life ‐ Not reported

3. Economic evaluation outcome

(a) Costs of the dressings and topical agents Cannova (1998) calculated material costs (using A$ 1997) and nursing time spent in completing the dressing protocol for each patient. The total approximate costs per dressing was lowest for combined dressing pad (A$4.39) compared to alginate (A$12.94) and antiseptic gauze (A$5.77)

(b) Cost‐effectiveness or cost‐benefit analysis Cannova (1998) did not find a significant difference in total cost per day between alginate (15.25 ± 1.26 A$) and gauze; A$19.36 ± 1.83 (p=0.069) or combined dressing pad; A$14.14 ± 1.71 (p=0.636) but the trial was underpowered to detect important differences.

(c) Hospitalisation period ‐ Not reported

Summary

Only 2 small trials have compared alginate with gauze for surgical wounds healing by secondary intention, and there is insufficient evidence of a difference in healing rates. Gauze use may be associated with less satisfaction and more pain but more research is needed.

Comparison 04: HYDROCOLLOID VERSUS GAUZE (1 trial)

One trial compared hydrocolloid with gauze dressings.

Viciano 2000 randomised 38 patients with open excision of pilonidal sinus healing by secondary intention, to one of two hydrocolloid dressings (Comfeel, n=12 or Varihesive, n=11) or gauze soaked with povidone iodine (n=15).

1. Primary outcome measure; wound healing

There was no difference in median time to healing between the groups.

2. Secondary outcome measures include pain, patient satisfaction and quality of life according to the scales used in the various articles.

(a) Pain Viciano 2000 measured pain per dressing change using a visual analogue scale (VAS) and compared the groups with the Mann‐Whitney test. Pain was lower in the hydrocolloid groups during the first 4 weeks (P <0.05) than in the gauze group. The difference appeared in the first dressing and it persisted until the fifteenth dressing. In the combined hydrocolloid dressings group pain was significantly lower in the first week; (median 25) compared with the gauze group (median 50)(P=0.05). However, the median weekly difference in pain was not significant during the second to fourth weeks.

(b) Exudate Dressings leaked exudate on 14 occasions in the hydrocolloid group. This was reported to be as a consequence of poor dressing adherence. Leaks were not reported in the gauze group.

(c) Complications and morbidity Viciano 2000 undertook microbiological analysis of samples collected from the wounds during the perioperative period. None of the intra‐operative samples grew pathogens, whilst one postoperative sample from the hydrocolloid group and five from the gauze group grew pathogens. The study authors report a significant difference in the growth of pathogens (p= 0.03). However, it is not clear how many cultures were collected, and we are therefore not able to calculate a RR or 95% CI.

(d) Patient satisfaction The hydrocolloid group patient comfort was rated as good or excellent, although how this was measured was not stated. No significant differences were noticed between the two wound dressings. No data or statistics are reported to support this.

(e) Quality of life data, generic or specific measures of quality of life ‐ Not reported

3. Economic evaluation outcome

(a) Costs of the dressings and topical agents Dressing costs reported as at July 1999 per unit were; hydrocolloid €4.00 (3.8 US$) and gauze €1.30 (1.3 US$).

(b) Cost‐effectiveness or cost‐benefit analysis Costs (as per July 1999) were calculated per patient to be €93.60 or 90.0 US$ for patients in the hydrocolloid group compared to €101.10 or 97.2 US$ per patient for gauze. How this was calculated is not stated. Viciano 2000 stated that, although hydrocolloid dressings are more expensive, conventional gauze dressings must be changed more frequently.

(c) Hospitalisation period ‐ Not reported

Summary

Only 1 small, study has compared hydrocolloid dressings with gauze for surgical wounds healing by secondary intention. There is no evidence of a difference in the effects of hydrocolloid and gauze on wound healing. Hydrocolloid dressings may be associated with lower pain levels, particularly in the first week, than gauze.

Comparison 5: GAUZE WITH ALOE VERA VERSUS GAUZE (1 trial)

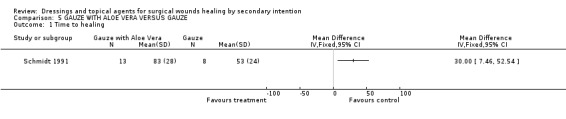

Schmidt 1991 randomised 40 patients with surgical wounds requiring healing by secondary intention after caesarean delivery or laparotomy for gynaecological surgery, to receive Aloe Vera gel plus traditional wet‐to‐dry treatment [n=20] or traditional wet‐to‐dry treatment alone [n=20].

1. Primary outcome measure; wound healing.

More patients were lost to follow up from the gauze group (n=12) than the Aloe vera group (n=5). These patients were excluded from the analysis which introduces bias and reduces our confidence that the results are true. Mean time to healing was reported as significantly greater with Aloe Vera compared with gauze, however the differential loss to follow up means that these results are un interpretable. Graph: Comparison 5, outcome 1.

2. Secondary outcome measures include pain, patient satisfaction and quality of life according to the scales used in the various articles.

(a) Pain ‐ Not reported. (b) Exudate ‐ Not reported.

(c) Complications and morbidity There were no adverse effects noted in either group during the study.

(d) Patient satisfaction ‐ Not reported. (e) Quality of life data, generic or specific measures of quality of life ‐ Not reported.

3. Economic evaluation outcome

(a) Costs of the dressings and topical agents ‐ Not reported. (b) Cost‐effectiveness or cost‐benefit analysis ‐ Not reported. (c) Hospitalisation period ‐ Not reported.

Summary

The single small trail of Aloe vera and gauze is significantly flawed by differential loss to follow up.

Comparison 06: FOAM VERSUS DEXTRANOMER BEADS (1 trial)

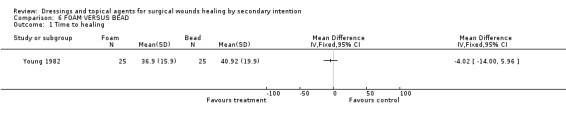

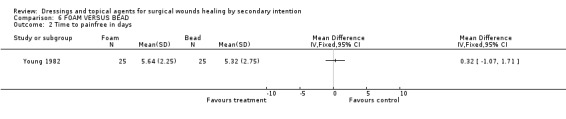

Young 1982 compared silastic foam dressing and dextranomer bead dressing in 50 patients with surgical wounds that have either broken down or have been left open postoperatively (wound breakdown, appendectomy for gangrenous or perforated appendix).

1. Primary outcome measure; wound healing

There was no significant difference in time to complete healing. Graph: Comparison 6, outcome 1.

2. Secondary outcome measures include pain, patient satisfaction and quality of life according to the scales used in the various articles

(a) Pain There was no difference in mean time to become pain free. Graph: Comparison 6, outcome 2.

(b) Exudate ‐ Not reported.

(c) Complications and morbidity Whilst Young 1982 stated that there was no difference between the groups in the time taken for disappearance of erythema, oedema and slough, no data were provided.

(d) Patient satisfaction ‐ Not reported. (e) Quality of life data, generic or specific measures of quality of life ‐ Not reported.

3. Economic evaluation outcome

(a) Costs of the dressings and topical agents ‐ Not reported. (b) Cost‐effectiveness or cost‐benefit analysis ‐ Not reported. (c) Hospitalisation period ‐ Not reported.

Summary

There is no evidence of a difference between foam and dextranomer in terms of time to wound healing or any of the secondary outcomes. There is only 1 poor quality trial.

Comparison 07: FOAM VERSUS ALGINATE (1 trial)

Berry 1996 randomised 20 patients with standard pilonidal sinus excision wounds to either polyurethane foam hydrophilic dressing followed by polyurethane foam sheets dressing or calcium sodium alginate dressing followed by a polyurethane foam sheet dressing.

1. Primary outcome measure; wound healing

Although a nine‐day difference in mean time to healing was reported, this difference was not statistically significant (mean time to healing for foam was 56.7 days, range 36 to 78 days, compared with 65.5 days (range 43 to 106 days) for alginate.

2. Secondary outcome measures include pain, patient satisfaction and quality of life according to the scales used in the various articles.

(a) Pain ‐ Not reported. (b) Exudate No difference was reported in leakage (Foam; 81% nil/slight versus alginate 73% nil/slight) (RR 1.11) or absorption capacity; foam; 85% good versus alginate; 86% good, RR 0.99. No raw data were given; therefore we were unable to calculate a 95% CI.

(c) Complications and morbidity ‐ Not reported.

(d) Patient satisfaction Ease of use and patient acceptance were assessed at weekly outpatient visits. However, whilst scores for alginates tended to be higher, insufficient data were provided to enable us to calculate statistical significance.

(e) Quality of life data, generic or specific measures of quality of life ‐ Not reported.

3. Economic evaluation outcome

(a) Costs of the dressings and topical agents ‐ Not reported. (b) Cost‐effectiveness or cost‐benefit analysis ‐ Not reported. (c) Hospitalisation period ‐ Not reported.

Summary

From one small trial there is insufficient evidence to inform on the relative effects of foam and alginate dressing on healing or secondary outcomes.

Comparison 08: PLASTER CAST VERSUS ELASTIC COMPRESSION (1 trial)

Vigier 1999 randomised 56 patients with open stump wounds after below knee amputation (due to arterial disease) to either a plaster cast interposed with a silicone sleeve directly on the skin and covered with a tubular piece of jersey sewn up at the stump end or elastic compression bandage.

1. Primary outcome measure; wound healing

Time to complete stump healing in days was significantly lower in the plaster cast group (71.2 days) compared to the elastic compression group (96.6 days; WMD ‐25.6 days 95% CI ‐49.1 to ‐2.12), Graph: Comparison 8, outcome 1.

2. Secondary outcome measures include pain, patient satisfaction and quality of life according to the scales used in the various articles

(a) Pain ‐ Not reported. (b) Exudate ‐ Not reported (c) Complications and morbidity ‐ Not reported. (d) Patient satisfaction ‐ Not reported. (e) Quality of life data, generic or specific measures of quality of life ‐ Not reported.

3. Economic evaluation outcome

(a) Costs of the dressings and topical agents ‐ Not reported. (b) Cost‐effectiveness or cost‐benefit analysis ‐ Not reported. (c) Hospitalisation period ‐ Vigier 1999 found a significant shorter hospital stay in favour of plaster cast (mean length of stay 99.8 days) compared to the elastic compression group ( mean length of stay 129.9 days), Graph: Comparison 8, outcome 2.

Summary

Lower limb amputation wounds healed significantly more quickly with plaster cast than with compression. Length of hospital stay was also shorter.

Discussion

We were unable to identify a single large, high quality RCT in this area. Only thirteen, poor quality trials were found, while worldwide all kinds of dressings and topical agents are used in wound care for surgical wounds healing by secondary intention. There is some evidence that patients may experience more pain and less satisfaction when gauze is used. Lower limb amputation wounds healed significantly more quickly when dressed with a plaster cast than with an elastic compression dressing. Although the supplementation of Aloe vera gel to a traditional gauze dressing increased the time to healing the results of this trial are unreliable due to the differential loss to follow up.

There are a number of limitations to the conclusions of this review. First, the thirteen trials included in this review used numerous different interventions and controls and endpoints. So there was a lack of replication of most comparisons. Foam versus (antiseptic) plain or impregnated gauze was the comparison studied most frequently(five trials).

Second, the methodological quality of the studies was disappointing; most trials were underpowered and therefore ran a great risk of failing to detect any clinically relevant differences as statistically significant. Other potential methodological flaws, such as unclearly described randomisation, lack of baseline comparability and lack of blind outcome assessment, further reduce the confidence to appreciate many of the individual study findings. We found no RCTs on the following dressing types: tulle dressings, semi‐permeable film dressing and topical agents: antibiotics, steroid preparations, steroid / antibiotic combination, oestrogen, enzymatic agents, growth factors, and collagen.

Third, there is also concern re. potentially biased reporting of secondary endpoints (e.g. pain), in that they may be more likely to be reported if a statistically significant benefit is found. Furthermore several of the studies report a great many outcomes over several time points, so increasing the likelihood of a type I error.

The studies summarised in this review are small trials, have methodological flaws, and clinicians may feel not convinced by the limited evidence presented in this review. The strength of a systematic review is to summarise or pool data from several, often small, trials to make an overall conclusion or estimate of effect. For example, in this review data could be pooled for only one comparison (gauze versus foam). Pooling of data was usually impossible due to: a) lack of replication of comparisons; b) lack of replication of objective outcome measurements (different scales were used for pain, satisfaction), c) outcomes measured at different, or d) surrogate measurements. Therefore, replication studies are needed as well as standards (validated scales) to measure wound healing (e.g. primarily expressed as time to complete healing and secondly expressed both as a percentage and absolute change in area), pain (e.g. 10‐point VAS), satisfaction and financial costs. To avoid the methodological flaws of the individual trials, future trials should include measures to help demonstrate comparability of treatment groups at baseline (or adjust for differences), be of sufficient power to detect true treatment effects, use true randomisation (computer generated codes), with allocation concealment and blinded outcome assessment by the effect reviewer. Thus, further evaluation in well‐designed RCTs of sufficient size is needed to detect any clinically as well as statistically significant differences in order to assess the effectiveness of dressings and topical agents for surgical wounds healing by secondary intention. Future research should also mention concomitant (e.g. secondary dressings and systemic) interventions, as these can have important effects on healing. Furthermore, randomised controlled trials require adequate reporting. The revised CONSORT statement (Moher 2003) lists 21 items that need to be reported to show readers whether or not a trial is likely to produce valid and reliable results. Cost effectiveness trials require adequate calculation, which includes all relevant items (Drummond 1996).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The use of gauze for the local treatment of surgical wounds healing by secondary intention should be considered carefully as it may be associated with greater pain or discomfort for the patient. Foam, alginate and hydrocolloid were associated with less pain than gauze in the few studies identified. We would like to stress that the evidence is weak, so further research is required to validate these findings and to address several unanswered questions, such as quality of life and complications, like exudate, leakage, and morbidity.

Implications for research.

Future studies should:

be adequately powered

use valid measures of wound healing

measure and report pain

be reported in accordance with CONSORT requirements

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 7 March 2012 | Amended | Additional table linked to text |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2002 Review first published: Issue 2, 2004

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 7 September 2010 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 15 June 2010 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 11 August 2009 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 23 July 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 2 October 2003 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the Dutch Cochrane Centre, especially to Dr RJPM Scholten.

Thanks to the following people who refereed the protocol for readability, relevance and methodological rigour: Editors of the Cochrane Wounds Group; Nicky Cullum (UK), Andrea Nelson (UK), Michelle Briggs (UK); Referees of the Cochrane Wounds Group; Liz Scanlon (UK), Nerys Woolacott (UK), Malcolm Brewster (UK), Anne Humphreys (UK), Andrew Jull (NZ).

Thanks to the support of the Cochrane Wounds Group, especially Nicky Cullum, Co‐Ordinating Editor and Sally Bell‐Syer, Review Group Co‐ordinator.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. FOAM VERSUS GAUZE.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Time to healing pooled | 5 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 District nursing visits | 3 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Hospital stay | 4 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 FOAM VERSUS GAUZE, Outcome 1 Time to healing pooled.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 FOAM VERSUS GAUZE, Outcome 2 District nursing visits.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 FOAM VERSUS GAUZE, Outcome 3 Hospital stay.

Comparison 3. ALGINATE VERSUS GAUZE.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Wound size reduction (cm2) per day | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Wound size reduction (cm3) per day | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Satisfaction with dressing. First week: during dressing changes (VAS 10‐point scale) | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4 Satisfaction with dressing. First week: between dressing changes (VAS 10‐point scale) | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5 Satisfaction with dressing. Last visit: during dressing changes (VAS 10‐point scale) | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6 Satisfaction with dressing. Last visit: between dressing changes (VAS 10‐point scale) | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 ALGINATE VERSUS GAUZE, Outcome 1 Wound size reduction (cm2) per day.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 ALGINATE VERSUS GAUZE, Outcome 2 Wound size reduction (cm3) per day.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 ALGINATE VERSUS GAUZE, Outcome 3 Satisfaction with dressing. First week: during dressing changes (VAS 10‐point scale).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 ALGINATE VERSUS GAUZE, Outcome 4 Satisfaction with dressing. First week: between dressing changes (VAS 10‐point scale).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 ALGINATE VERSUS GAUZE, Outcome 5 Satisfaction with dressing. Last visit: during dressing changes (VAS 10‐point scale).

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 ALGINATE VERSUS GAUZE, Outcome 6 Satisfaction with dressing. Last visit: between dressing changes (VAS 10‐point scale).

Comparison 5. GAUZE WITH ALOE VERA VERSUS GAUZE.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Time to healing | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 GAUZE WITH ALOE VERA VERSUS GAUZE, Outcome 1 Time to healing.

Comparison 6. FOAM VERSUS BEAD.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Time to healing | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Time to painfree in days | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 FOAM VERSUS BEAD, Outcome 1 Time to healing.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 FOAM VERSUS BEAD, Outcome 2 Time to painfree in days.

Comparison 8. PLASTER CAST VERSUS ELASTIC COMPRESSION.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Time to healing | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Hospitalisation | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 PLASTER CAST VERSUS ELASTIC COMPRESSION, Outcome 1 Time to healing.

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 PLASTER CAST VERSUS ELASTIC COMPRESSION, Outcome 2 Hospitalisation.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Berry 1996.

| Methods | RCT Method of randomisation not stated Setting: Hospital and outpatient clinic, United Kingdom | |

| Participants | N=20 Patients with standard pilonidal sinus excision wounds | |

| Interventions | Intervention : Polyurethane foam hydrophilic dressing (Allevyn cavity wounds dressing; followed by polyurethane foam sheets dressing (Allevyn) when the wound no longer had significant depth Comparison: Calcium sodium alginate dressing (Kaltostat) followed by a polyurethane foam sheet dressing (Lynofoam) when the wound no longer had significant depth | |

| Outcomes | Healing Exudate Patient satisfaction | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Cannova 1998 a vs ag.

| Methods | ||

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Cannova 1998 a vs c.

| Methods | RCT ‐ Method of randomisation not stated Setting:Hospital, Australia | |

| Participants | N=36 Patients with surgical abdominal wounds (wound breakdown > 3 cm) | |

| Interventions | Intervention: alginate Comparison 1: a gauze moistened with sodium hypochlorite (0.05%) Comparison 2: a combined dressing pad (cotton wool and gauze covered with a secondary film dressing). | |

| Outcomes | Healing Pain Patient satisfaction Cost | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Eldrup 1985.

| Methods | RCT Method of randomisation. Randomisation by drawing of lots. Setting: Hospital and outpatient clinic, Denmark | |

| Participants | N=33 Patients with open therapy after pilonidal sinus excision. | |

| Interventions | Intervention Silastic foam dressing n=17 Comparison:Gauze with Choramine n=16 | |

| Outcomes | Healing Patient satisfaction Cost Musing time | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Goode 1979.

| Methods | RCT Method of randomisation:Cards drawn from sealed envelopes Setting: Hospital and outpatient clinic, United Kingdom | |

| Participants | N=20 Patients with opened infected surgical wounds after bowel surgery (appendectomy or bowel surgery) | |

| Interventions | Intervention:dextranomer polysaccharide beads (Debrisan) Comparison:Eusol ribbon gauze | |

| Outcomes | Healing Cost Hospitalisation | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Guillotreau 1996.

| Methods | RCT(multicentre)Method of randomisation not stated Setting:Hospital, France. | |

| Participants | N=70 Patients with incision and drainage of pilonidal abscess | |

| Interventions | Intervention: Calcium alginate rope Comparison: packing with gauze soaked in povidone iodine | |

| Outcomes | Healing Pain Patient satisfaction | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Macfie 1980.

| Methods | RCT Method of randomisation not stated Randomised on postoperative day 14 Setting: hospital and outpatient clinic, UK. | |

| Participants | N=50 Patients with open perineal wounds after abdominal perineal excision of the rectum ( proctocolectomy or rectal excision) | |

| Interventions | Intervention: Silicone foam elastomer (Silastic, Dow Corning Ltd) n=25 Comparison: Ribbon gauze soaked in mercuric chloride antiseptic solution. n=25 | |

| Outcomes | Healing Pain Cost | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Meyer 1997.

| Methods | RCT Method of randomisation not stated. Setting: Hospital, Germany | |

| Participants | N=43 Patients with laparotomy or surgical incision of an abscess | |

| Interventions | Intervention: Polyurethane foam containing hydroactive particles (Cutin ova cavity dressing, Beiersdorf AG) n=21 Comparison: Moist cotton gauze covered by a simple surgical dressing; solution used to moisten the gauze was not stated. n=22 | |

| Outcomes | Healing Pain | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Schmidt 1991.

| Methods | RCT Method of randomisation:Stratified randomisation by computer allocation. Setting: Outpatient clinic, USA. | |

| Participants | N=40 Patients with surgical wounds requiring healing by secondary intention after (caesarean delivery or laparotomy for gynaecological surgery). All wounds had opened spontaneously or had been drained to treat a seroma, haematoma or wound abscess before referral. | |

| Interventions | Intervention: Aloe vera gel (Carrington Dermal wound gel formulation) was supplemented on traditional treatment. Comparison: Traditional treatment. The wound was debrided with either a gauze pad or a scalpel as required and irrigated with high‐volume, high pressure irrigations. A wet‐to‐dry dressing was applied. This was repeated every 8 hours until the commencement of granulation, after which treatment was repeated every 12 hours. | |

| Outcomes | Healing | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Viciano 2000.

| Methods | RCT Method of randomisation not stated. Setting: Outpatient clinic, Spain | |

| Participants | N=38 Patients with open excision of Pilonidal sinus healing by second intention. | |

| Interventions | Intervention 1: Comfeel Intervention 2: Varihesive Comparison: Gauze with povidone iodine | |

| Outcomes | Healing Pain Complications and morbidity Patient satisfaction Cost | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Vigier 1999.

| Methods | RCT Method of randomisation not stated. Setting: Rehabilitation center, France | |

| Participants | N=56 Patients with below knee amputation because of arterial disease and initially had an open stump. | |

| Interventions | Intervention: A plaster cast (supracondylar‐type) socket was fitter on the stumps, interposed with a silicone sleeve directly on the skin and covered with a tubular piece of jersey sewn up at the stump end. Comparison: Elastic compression bandage, which were only removed for dressing changes, which was as thin as possible. | |

| Outcomes | Healing Hospitalisation | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Walker 1991.

| Methods | RCT Method of randomisation not stated Setting: Hospital and outpatient clinic, United Kingdom. | |

| Participants | N=75 Patients with open excision of Pilonidal sinus (n=38) and abscesses (n=37). | |

| Interventions | Intervention: Silicone foam cavity dressing (Silastic foam) pilonidal sinus n=17 abscesses n=17 Comparison: Eusol‐soaked gauze at half strength. pilonidal sinus n=21 abscesses n=20 | |

| Outcomes | Healing | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Walker 1991 abcess.

| Methods | ||

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Williams 1981.

| Methods | RCT Method of randomisation not stated. Setting: Hospital and outpatient clinic, United Kingdom | |

| Participants | N=80 Patients with excision of a pilonidal sinus | |

| Interventions | Intervention: Silastic foam cavity dressing n=44 Comparison:Gauze soaked in 0.5% aqueous solution of chlorhexidine (Hibitane) n=36 | |

| Outcomes | Healing Patient satisfaction Nursing time Hospitalisation | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Young 1982.

| Methods | RCT Method of randomisation: Random card system. Setting: Hospital and outpatient clinic, United Kingdom | |

| Participants | N=50 Patients with surgical wounds that have either broken down or have been left open postoperatively (wound breakdown, appendectomy for gangrenous or perforated appendix). | |

| Interventions | Intervention: Debrisan plus standard treatment of change of dressing twice per day. Comparison: Silastic foam dressing. | |

| Outcomes | Healing Pain Complications | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Becker | Controlled clinical trial Controlled clinical trial: bovine collagen or no‐collagen in patients undergoing facial Mohs surgery |

| Blight | Controlled clinical trial A clinical trial: Jelonet and OpSite in elderly patients with donor sites. |

| Brown | Skin grafts A prospective, randomized, double‐blind clinical trial: silver sulfadiazine cream with or without epidermal growth factor in patients with skin‐graft‐donor sites |

| Butterworth | Controlled clinical trial Controlled clinical trial; Allevyn and Silastic foam in patients with cavity wounds. |

| Chang | Skin grafts Randomized Controlled Trial: Moist dressing changes or tissue‐engineered skin graft in patients with ischaemic foot wounds |

| Chatterjee | Controlled clinical trial and Skin grafts A controlled comparative study of the use of porcine xenograft porcine skin graft or the conventional method with paraffin gauze the treatment of partial thickness skin loss of the limbs, mainly due to burns |

| Cordts | Not surgical wound A prospective, randomized trial: Unna's boot or Duoderm CGF hydroactive dressing plus compression in patients with venous leg ulcers |

| Dawson | Controlled clinical trial Controlled clinical trial: Calcium alginate or saline soaked gauze in patients with abscesses |

| Dovison | Nail ablation Randomized Controlled Trial: a medicated wound dressing 10% povidone iodine), an amorphous hydrogel dressing (Intrasite Gel), and a control dressing (paraffin gauze) in patients with nail matrix ablation |

| Foster 1997 | Not measured primary endpoint wound healing. Prospective randomized controlled trial: a traditional dressing (ribbon gauze soaked in proflavine) or a modern hydrofibre dressing in patients with acute surgical wounds left to heal by secondary intention. |

| Foster 2000 | Not measured primary endpoint wound healing. A blinded randomised study: a hydrofibre dressing (Aquacel) and an alginate dressing (Sorbsan) in patients with acute surgical wounds left to heal by secondary intention |

| Giele | Skin grafts A prospective randomised trial: alginate (Kaltostat(R)) or an adhesive retention tape (Mefix(R)) in patients with split skin grafts |

| Himel | Skin grafts A prospective, randomized, controlled study: VENTEX Wound Dressing System or Xeroform gauze in patients with donor site wound |

| Ho | Skin grafts A prospective controlled clinical study: Hyphecan (1‐4,2‐acetamide‐deoxy‐B‐D‐glucan polymer) or Kaltostat (calcium sodium alginate) in patients with skin donor sites |

| Innes | Skin grafts A prospective, controlled matched pair study: Acticoat, (a silver‐coated dressing) or Allevyn (an occlusive moist‐healing environment material) in patients with donor site wounds |

| Joseph | Not Surgical Wound A prospective randomized trial: vacuum‐assisted closure or standard therapy of chronic nonhealing wounds. |

| Kikta | Not Surgical Wound A prospective, randomized trial: Unna's boots or hydroactive dressing in patients with venous stasis ulcers |

| Krupski | Not Surgical wounds A randomized, prospective, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study: topically applied platelet‐derived wound healing or placebo in patients with chronic nonhealing wounds |

| Levine | Not Surgical Wounds Randomized Controlled Trial: cadaver allograft, fresh porcine xenograft, formalinized xenograft, or "wet‐to‐dry" applications of coarse mesh gauze in patients with large area granulating wounds |

| Martin | Not surgical wounds A randomised, double‐blind, controlled trial: streptokinase/streptodornase (Varidase) in a hydrogel (KY Jelly) or the hydrogel alone in debridement of Grade IV pressure sores. |

| Mateev | Controlled clinical trial Controlled clinical trial: of some of the properties of the film‐forming dressing "Rivafilm". |

| Mishima | Not topical but systemic treatment A open, randomised, and controlled trial: factor‐XIII concentrate: 61.9% (dosage: 750 IU factor XIII for 3 days) or 76.2% (dosage: 1500 IU factor XIII for 3 days) or 10.5% without factor XIII substitution in patients with postoperative wound healing disorders |

| Moore | Not measured primary endpoint wound healing. Prospective randomized controlled trial: a traditional dressing (ribbon gauze soaked in proflavine) or a modern hydrofibre dressing in patients with acute surgical wounds left to heal by secondary intention. |

| Morgan | Controlled clinical trial Controlled clinical trial: skin grafting or healing by granulation in patients with excisions |

| O'Donoghue | Skin grafts A prospective controlled trial: calcium alginate or paraffin gauze on split skin graft donor sites |

| Pham | Not Surgical Wound A prospective, randomized, clinical, placebo controlled trial: skin equivalent or woven gauze kept moist by saline in patients with nonischemic, non‐infected diabetic foot ulcers. |

| Pollak | Not surgical Wounds A randomized controlled study: human dermal replacement (dermal fibroblasts grown on a bioabsorbable mesh) or conventional treatment in patients with diabetic foot ulcers |

| Prasad | Skin graft A prospective controlled trial: Biobrane or scarlet red in patients with skin graft donor site |

| Quell | Controlled clinical trial Controlled clinical trial: Semi occlusive dressing or Vaseline gauze dressings in patients with fingertip amputations. |

| Razzak | Not Surgical Wound A randomised trial: antibiotics or antibiotics and dressing with local insulin application in patients with diabetic foot complication |

| Ricci | Controlled clinical trial Controlled clinical trial: foam dressing versus gauze soaks in patients with surgical wounds healing by secondary intention. |

| Rives | Not adult A controlled, randomized, clinical trial: calcium alginate dressing or a paraffin gauze in children with scalp donor sites |

| Rossmann | Skin graft A comparative evaluation patients randomly selected for a test product or control comprising: 1) oxidized regenerated cellulose; 2) absorbable gelatin sponge; or 3) sterile gauze with external pressure as the control in graft donor site |

| Rubin | Not Surgical Wound A randomized prospective study: polyurethane foam dressings or standard semirigid impregnated gauze dressings in patients with venous stasis cutaneous ulcerations |

| Scriven | Not Surgical wound A prospective randomised trial: four‐layer or short stretch compression bandages in patients with venous leg ulcers. |

| Smith | Not Surgical Wound A randomized study: sequential gradient intermittent pneumatic compression or no compression in patients with venous ulcers |

| Steed, 1992 | Not Surgical Wound A randomized, double‐blind trial: of topically applied CT‐102 APST or placebo (normal saline) gauze dressings in patients with nonhealing diabetic neurotrophic foot ulcers |

| Steed, 1995 | Not Surgical Wounds A double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, multicenter study: topical rhPDGF‐BB (2.2 mug/cm2 of ulcer area) or placebo in patients with chronic diabetic ulcers. |

| Summer | Primary healing Prospective Trial, Xeroform gauze or Unna cap‐‐Aquaphor gauze and Dome Paste gauze in patients with deep scalp donor sites |

| Terren | Skin grafts A comparative prospective and cross‐over study: occlusive hydrocolloid dressing, semi occlusive hydrocolloid, polyurethane sheet or conventional dressing in patients with skin graft donor site |

| Van Gils | Nail ablation A prospective clinical trial: collagen‐alginate wound dressing or soaks and daily dressing changes in the postoperative management of chemical matricectomies. |

| Veves | Not Surgical Wounds A randomized prospective trial: Graftskin (a living skin equivalent) or saline‐moistened gauze in patients with diabetic foot ulcers |

| Vogel | Skin graft A randomized controlled trial: freeze‐dried amniotic membrane or not in patient with donor site |

| Weber | Skin graft A prospective randomized trial: hydrophilic semipermeable absorbent polyurethane foam dressing or petrolatum gauze dressing in patients with donor sites. |

| Williams | Not measured primary endpoint wound healing. A randomised trial; calcium alginate dressing and sodium alginate dressing in patients with surgical wounds |

Contributions of authors