To The Editor: We recently reported the results of a phase 1 trial of a messenger RNA vaccine, mRNA-1273, to prevent infection with SARS-CoV-2; those interim results covered a period of 57 days after the first vaccination.1,2 Here, we describe immunogenicity data 119 days after the first vaccination (90 days after the second vaccination) in 34 healthy adult participants in the same trial who received two injections of vaccine at a dose of 100 μg. The injections were received 28 days apart. The recipients were stratified according to age (18 to 55 years, 56 to 70 years, or ≥71 years), and the assays used have been described previously.1,2

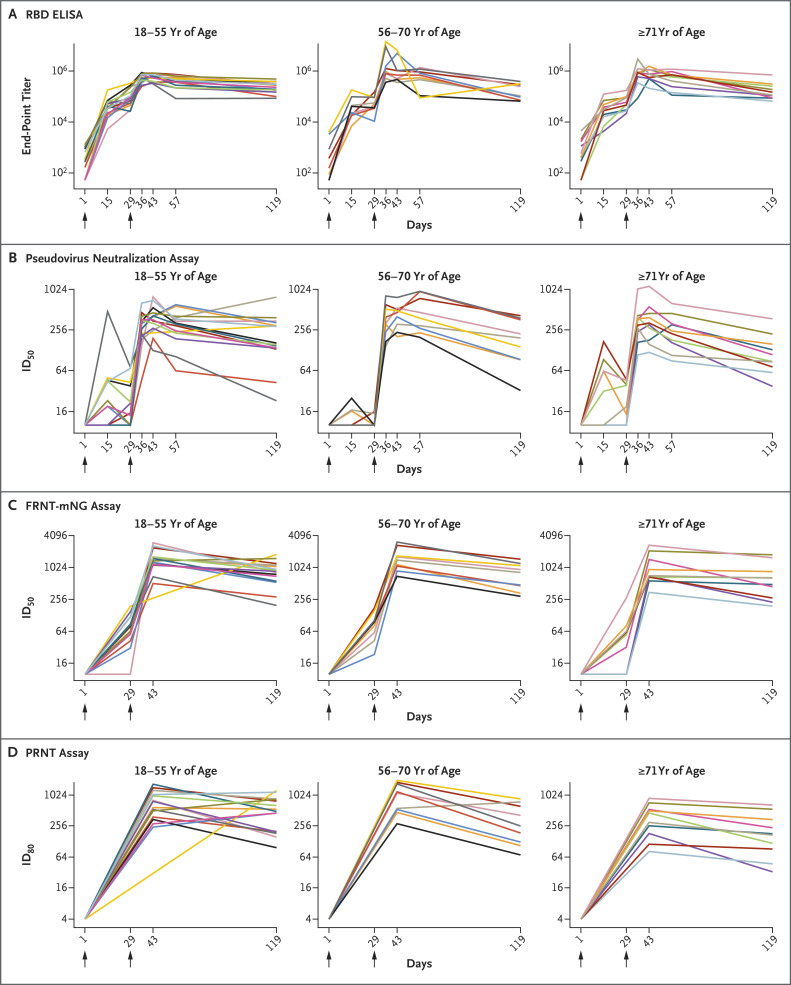

At the 100-μg dose, mRNA-1273 produced high levels of binding and neutralizing antibodies that declined slightly over time, as expected, but they remained elevated in all participants 3 months after the booster vaccination. Binding antibody responses to the spike receptor–binding domain were assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. At the day 119 time point, the geometric mean titer (GMT) was 235,228 (95% confidence interval [CI], 177,236 to 312,195) in participants 18 to 55 years of age, 151,761 (95% CI, 88,571 to 260,033) in those 56 to 70 years of age, and 157,946 (95% CI, 94,345 to 264,420) in those 71 years of age or older (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Time Course of SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Binding and Neutralization Responses after mRNA-1273 Vaccination.

Shown are data from 34 participants who were stratified according to age: 18 to 55 years of age (15 participants), 56 to 70 years of age (9 participants), and 71 years of age or older (10 participants). All the participants received 100 μg of mRNA-1273 on days 1 and 29, indicated by arrows. The titers shown are the binding to spike receptor–binding domain (RBD) protein (the end-point dilution titer) assessed on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) on days 1, 15, 29, 36, 43, 57, and 119 (Panel A); the 50% inhibitory dilution (ID50) titer on pseudovirus neutralization assay on days 1, 15, 29, 36, 43, 57, and 119 (Panel B); the ID50 titer on focus reduction neutralization test mNeonGreen (FRNT-mNG) assay on days 1, 29, 43, and 119 (Panel C); and the 80% inhibitory dilution (ID80) titer on plaque-reduction neutralization testing (PRNT) assay on days 1, 43, and 119 (Panel D). Data for days 43 and 57 are missing for 1 participant in the 18-to-55-year stratum for whom samples were not obtained at those time points. Each line represents a single participant over time.

Serum neutralizing antibodies continued to be detected in all the participants at day 119. On a pseudovirus neutralization assay, the 50% inhibitory dilution (ID50) GMT was 182 (95% CI, 112 to 296) in participants who were between the ages of 18 and 55 years, 167 (95% CI, 88 to 318) in those between the ages of 56 and 70 years, and 109 (95% CI, 68 to 175) in those 71 years of age or older. On the live-virus focus reduction neutralization test mNeonGreen assay, the ID50 GMT was 775 (95% CI, 560 to 1071), 685 (95% CI, 436 to 1077), and 552 (95% CI, 321 to 947) in the same three groups, respectively. On the live-virus plaque-reduction neutralization testing assay, the 80% inhibitory dilution GMT was similarly elevated at 430 (95% CI, 277 to 667), 269 (95% CI, 134 to 542), and 165 (95% CI, 82 to 332) in the same three groups, respectively (Figure 1).

At day 119, the binding and neutralizing GMTs exceeded the median GMTs in a panel of 41 controls who were convalescing from Covid-19, with a median of 34 days since diagnosis (range, 23 to 54).2 No serious adverse events were noted in the trial, no prespecified trial-halting rules were met, and no new adverse events that were considered by the investigators to be related to the vaccine occurred after day 57.

Although correlates of protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans are not yet established, these results show that despite a slight expected decline in titers of binding and neutralizing antibodies, mRNA-1273 has the potential to provide durable humoral immunity. Natural infection produces variable antibody longevity3,4 and may induce robust memory B-cell responses despite low plasma neutralizing activity.4,5 Although the memory cellular response to mRNA-1273 is not yet defined, this vaccine elicited primary CD4 type 1 helper T responses 43 days after the first vaccination,2 and studies of vaccine-induced B cells are ongoing. Longitudinal vaccine responses are critically important, and a follow-up analysis to assess safety and immunogenicity in the participants for a period of 13 months is ongoing. Our findings provide support for the use of a 100-μg dose of mRNA-1273 in an ongoing phase 3 trial, which has recently shown a 94.5% efficacy rate in an interim analysis.

Supplementary Appendix

Disclosure Forms

This letter was published on December 3, 2020, at NEJM.org.

Footnotes

Supported by grants (UM1AI148373, to Kaiser Washington; UM1AI148576, UM1AI148684, and NIH P51 OD011132, to Emory University; NIH AID AI149644, to the University of North Carolina; UM1Al148684-01S1, to Vanderbilt University Medical Center; and HHSN272201500002C, to Emmes) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH); by a grant (UL1 TR002243, to Vanderbilt University Medical Center) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH; and by the Dolly Parton Covid-19 Research Fund (to Vanderbilt University Medical Center). Laboratory efforts were in part supported by the Emory Executive Vice President for Health Affairs Synergy Fund award, the Center for Childhood Infections and Vaccines, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Covid-Catalyst-I3 Funds from the Woodruff Health Sciences Center and Emory School of Medicine, and North Carolina Policy Collaboratory at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, with funding from the North Carolina Coronavirus Relief Fund established and appropriated by the North Carolina General Assembly. Additional support was provided by the Intramural Research Program of the Vaccine Research Center, NIAID, NIH. Funding for the manufacture of mRNA-1273 phase 1 material was provided by the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovation.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Jackson LA, Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, et al. An mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 — preliminary report. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1920-1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, Widge AT, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-1273 vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med. 10.1056/NEJMoa2028436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gudbjartsson DF, Norddahl GL, Melsted P, et al. Humoral immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in Iceland. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1724-1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dan JM, Mateus J, Kato Y, et al. Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for greater than six months after infection. November 16, 2020. (https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.11.15.383323v1). preprint.

- 5.Robbiani DF, Gaebler C, Muecksch F, et al. Convergent antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in convalescent individuals. Nature 2020;584:437-442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.