Highlights

-

•

The novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pneumonia has caused 2033 confirmed cases, including 56 deaths in mainland China, by 2020-01-26 17:06.

-

•

We aim to estimate the basic reproduction number of 2019-nCoV in Wuhan, China using the exponential growth model method.

-

•

We estimated that the mean R 0 ranges from 2.24 to 3.58 with an 8-fold to 2-fold increase in the reporting rate.

-

•

Changes in reporting likely occurred and should be taken into account in the estimation of R 0.

Keywords: Basic reproduction number, Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)

Abstract

Backgrounds

An ongoing outbreak of a novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pneumonia hit a major city in China, Wuhan, December 2019 and subsequently reached other provinces/regions of China and other countries. We present estimates of the basic reproduction number, R0, of 2019-nCoV in the early phase of the outbreak.

Methods

Accounting for the impact of the variations in disease reporting rate, we modelled the epidemic curve of 2019-nCoV cases time series, in mainland China from January 10 to January 24, 2020, through the exponential growth. With the estimated intrinsic growth rate (γ), we estimated R0 by using the serial intervals (SI) of two other well-known coronavirus diseases, MERS and SARS, as approximations for the true unknown SI.

Findings

The early outbreak data largely follows the exponential growth. We estimated that the mean R0 ranges from 2.24 (95%CI: 1.96–2.55) to 3.58 (95%CI: 2.89–4.39) associated with 8-fold to 2-fold increase in the reporting rate. We demonstrated that changes in reporting rate substantially affect estimates of R0.

Conclusion

The mean estimate of R0 for the 2019-nCoV ranges from 2.24 to 3.58, and is significantly larger than 1. Our findings indicate the potential of 2019-nCoV to cause outbreaks.

Introduction

The atypical pneumonia case, caused by a novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), was first reported and confirmed in Wuhan, China on December 31, 2019 (World Health Organization, 2020a). As of January 26 (17:00 GMT), 2020, there have been 2033 confirmed cases of 2019-nCoV infections in mainland China, including 56 deaths (National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China, 2020). The 2019-nCoV cases were also reported in Thailand, Japan, Republic of Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan and the US, and all of these cases were exported from Wuhan; see the World Health Organization (WHO) news release https://www.who.int/csr/don/en/ from January 14–21. The outbreak is still ongoing. A recently published preprint by Imai et al. estimated that a total of 1723 (95% CI: 427-4471) cases of 2019-nCoV infections in Wuhan had onset of symptoms by January 12, 2020 (Imai et al., 2020). The likelihood of travel related risks of disease spreading is suggested by Bogoch et al. (2020), which indicates the potentials of regional and global spread (Leung et al., 2020).

To the best of our knowledge, there is no existing peer-reviewed literature quantifying the transmissibility of 2019-nCoV as of January 22, 2020. In this study, we estimated the transmissibility of 2019-nCoV via the basic reproduction number, R 0, based on the limited data in the early phase of the outbreak.

Methods

We obtained the number of 2019-nCoV cases time series data in mainland China released by Wuhan Municipal Health Commission, China and National Health Commission of China from January 10 to January 24, 2020 from (Wuhan Municipal Health Commission, China, 2020). All cases were laboratory confirmed following the case definition by the National Health Commission of China (National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China, 2020). Although the date of submission of this study is January 26, we choose to use data up to January 24. Note that the data of the most recent few days contain a number of infections that were infected outside Wuhan due to travel, and thus this part of the infections is excluded from the analysis.

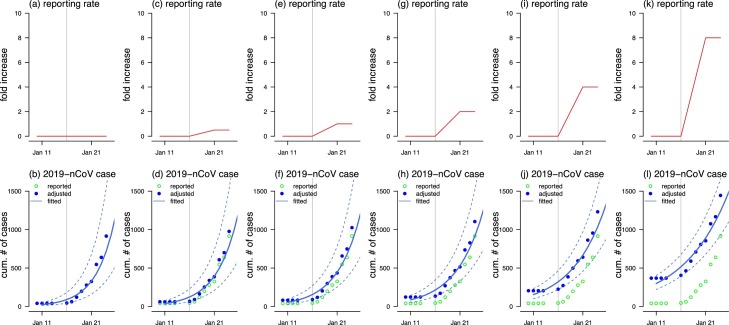

Although there were cases confirmed on or before January 16, the official diagnostic protocol was released by WHO on January 17 (World Health Organization, 2020b). To adjust the impact of this event, we considered a time-varying reporting rate that follows a linear increasing trend, motivated by the previous study (Wu et al., 2010). We assumed that the reporting rate, r(t), started increasing on January 17, and stopped at the maximal level on January 21. The reporting rate increase corresponds to accounts for the announcement on improving the 2019-nCoV surveillance of the Hubei provincial government (Hubei provincial government, 2020). The length of the reporting increasing part roughly equals the average of the incubation periods of two other well-known coronavirus diseases, i.e., the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), i.e., 5 days (Bauch et al., 2005, Lin et al., 2018, Donnelly et al., 2003). Denoting the daily reported number of new cases by c(t) for the t-th day, then the adjusted cumulative number of cases, C(t), is . Instead of finding the exact value of r(t), we calculated the fold change in r(t) that is defined by the ratio of r on January 10 over that on January 24 minus 1. We illustrated six scenarios with 0- (no change), 0.5-, 1-, 2-, 4- and 8-fold increase in reporting rate, see Figure 1 (a), (c), (e), (g), (i) and (k).

Figure 1.

The scenarios of the change in the reporting rate (top panels) and the exponential growth fitting (bottom panels). The top panels, i.e., (a), (c), (e), (g), (i) and (k), show the assumed change in the reporting rate. The bottom panels, i.e., (b), (d), (f), (h), (j) and (l), show the reported (or observed, green circles), adjusted (blue dots) and fitted (blue curve) number of 2019-nCoV infections, and the blue dashed lines are the 95%CI. The vertical grey line represents the date of January 16, 2020, after which the official diagnostic protocol was released by the WHO (World Health Organization, 2020). Panels (a) and (b) show the scenarios that the reporting rate was unchanged. Panels (c) and (d) show the scenarios that the reporting rate increased by 0.5-fold. Panels (e) and (f) show the scenarios that the reporting rate increased by 1-fold. Panels (g) and (h) show the scenarios that the reporting rate increased by 2-fold. Panels (i) and (j) show the scenarios that the reporting rate increased by 4-fold. Panels (k) and (l) show the scenarios that the reporting rate increased by 8-fold.

Following previous studies (Zhao et al., 2019, de Silva et al., 2009), we modelled the epidemic curve obeying the exponential growth. The nonlinear least square (NLS) framework is adopted for data fitting and parameter estimation. The intrinsic growth rate (γ) of the exponential growth was estimated, and the basic reproduction number could be obtained by R 0 = 1/M(−γ) with 100% susceptibility for 2019-nCoV at this early stage. The function M(∙) is the Laplace transform, i.e., the moment generating function, of the probability distribution for the serial interval (SI) of the disease (Zhao et al., 2019, Wallinga and Lipsitch, 2007), denoted by h(k) and k is the mean SI. Since the transmission chain of 2019-nCoV remains unclear, we adopted the SI information from SARS and MERS, which share a similar pathogen as 2019-nCoV. We modelled h(k) as Gamma distributions with a mean of 7.6 days and standard deviation (SD) of 3.4 days for MERS (Assiri et al., 2013), and mean of 8.4 days and SD of 3.8 days for SARS (Lipsitch et al., 2003) as well as their average, see the row heads in Table 1 for each scenario.

Table 1.

The summary table of the estimated basic reproduction number, R0, under different scenarios. The estimated R0 is shown as in the ‘median (95%CI)’ format. The ‘reporting rate increased’ indicates the number of fold increase in the reporting rate from January 17, when WHO released the official diagnostic protocol (World Health Organization, 2020b), to January 20, 2020.

| Reporting rate increased | Estimated R0 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Same as MERS SI 7.6 ± 3.4 | SI in average 8.0 ± 3.6 | Same as SARS SI 8.4 ± 3.8 | |

| (unchanged) | 5.31 (3.99–6.96) | 5.71 (4.24–7.54) | 6.11 (4.51–8.16) |

| 0.5-fold | 4.52 (3.49–5.76) | 4.82 (3.69–6.20) | 5.14 (3.90–6.67) |

| 1-fold | 4.01 (3.17–5.02) | 4.26 (3.34–5.38) | 4.53 (3.51–5.76) |

| 2-fold | 3.38 (2.75–4.12) | 3.58 (2.89–4.39) | 3.77 (3.02–4.67) |

| 4-fold | 2.73 (2.31–3.22) | 2.86 (2.40–3.39) | 3.00 (2.50–3.58) |

| 8-fold | 2.16 (1.90–2.45) | 2.24 (1.96–2.55) | 2.32 (2.02–2.66) |

Note: ‘SI’ is serial interval. ‘MERS’ is Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, and ‘SARS’ is the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome.

Results and discussion

The exponential growth fitting results are shown in Figure 1(b), (d), (f), (h), (j) and (l). The coefficient of determination, R-squared, ranges from 0.91 to 0.92 for all reporting rate changing scenarios, which implies that the early outbreak data were largely following the exponential growth. In Table 1, we estimated that the R 0 ranges from 2.24 (95%CI: 1.96-2.55) to 5.71 (95%CI: 4.24-7.54) associated with an 8-fold to 0-fold increase in the reporting rate. All R 0 estimates are significantly larger than 1, which indicates the potential of 2019-nCoV to cause outbreaks. Since the official diagnostic protocol was released by WHO on January 17 (World Health Organization, 2020b), an increase in the diagnosis and reporting of 2019-nCoV infections probably occurred. Thereafter, the daily number of newly reported cases started increasing around January 17, see Figure 1, which implies that more infections were likely being diagnosed and recorded. We suggested that changes in reporting might exist, and thus it should be considered in the estimation, i.e., 8-, 4- and 2-fold changes are more likely than no change in the reporting efforts. Although six scenarios about the reporting rate were explored in this study, the real situation is difficult to determine given limited data and (almost) equivalent model fitting performance in terms of R-squared. However, with increasing reporting rate, we found the mean R 0 is likely to be between 2 and 3.

Our analysis and estimation of R 0 rely on the accuracy of the SI of 2019-nCoV, which remains unknown as of January 25. In this work, we employed the SIs of SARS and MERS as approximations to that of 2019-nCoV. The determination of SI requires knowledge of the chain of disease transmission that needs a sufficient number of patient samples and periods of time for follow-up (Cowling et al., 2009), and thus this is unlikely to be achieved shortly. However, using SIs of SARS and MERS as approximation could provide an insight to the transmission potential of 2019-nCoV at the early stage of the outbreak. We reported that the mean R 0 of 2019-nCoV is likely to be from 2.24 (8-fold) to 3.58 (2-fold), and it is largely in the range of those of SARS, i.e., 2-5 (Bauch et al., 2005, Lipsitch et al., 2003, Wallinga and Teunis, 2004), and MERS, i.e., 2.7-3.9 (Lin et al., 2018).

We note that WHO reported the basic reproduction number for the human-to-human (direct) transmission ranged from 1.4 to 2.5 (World Health Organization, 2020b), which is marginally lower than ours. However, many of the existing online preprints estimate the mean R 0 ranging from 2 to 5 (Imai et al., 2020, Riou and Althaus, 2020, Read et al., 2020, Shen et al., 2020), which is largely consistent with our results.

Conclusion

We estimated the mean R 0 of 2019-nCoV ranging from 2.24 (95%CI: 1.96-2.55) to 3.58 (95%CI: 2.89-4.39) if the reporting effort has been increased by a factor of between 8- and 2-fold, respectively, after the diagnostic protocol released on January 17, 2020 and many medical supplies reached Wuhan.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethical approval or individual consent was not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials used in this work were publicly available.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Funding

DH was supported by General Research Fund (Grant Number 15205119) of the Research Grants Council (RGC) of Hong Kong, China. WW was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number 61672013) and Huaian Key Laboratory for Infectious Diseases Control and Prevention (Grant Number HAP201704), Huaian, Jiangsu, China.

Disclaimer

The funding agencies had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Authors contributions

All authors conceived the study, carried out the analysis, discussed the results, drafted the first manuscript, critically read and revised the manuscript, and gave final approval for publication.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge anonymous colleagues for helpful comments.

References

- Assiri A., McGeer A., Perl T.M., Price C.S., Al Rabeeah A.A., Cummings D.A., Alabdullatif Z.N., Assad M., Almulhim A., Makhdoom H. Hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. New Engl J Med. 2013;369(5):407–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauch C.T., Lloyd-Smith J.O., Coffee M.P., Galvani A.P. Dynamically modeling SARS and other newly emerging respiratory illnesses: past, present, and future. Epidemiol (Cambridge, Mass) 2005;16(6):791–801. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000181633.80269.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogoch I.I., Watts A., Thomas-Bachli A., Huber C., Kraemer M.U., Khan K. Pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: potential for international spread via commercial air travel. J Travel Med. 2020 doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowling B.J., Fang V.J., Riley S., Peiris J.M., Leung G.M. Estimation of the serial interval of influenza. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass) 2009;20(3):344. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31819d1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Silva U., Warachit J., Waicharoen S., Chittaganpitch M. A preliminary analysis of the epidemiology of influenza A (H1N1) v virus infection in Thailand from early outbreak data, June-July 2009. Eurosurveillance. 2009;14(31):19292. doi: 10.2807/ese.14.31.19292-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly C.A., Ghani A.C., Leung G.M., Hedley A.J., Fraser C., Riley S. Epidemiological determinants of spread of causal agent of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. Lancet (London, England) 2003;361(9371):1761–1766. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13410-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubei provincial government . Hubei provincial government; 2020. Strengthening the new coronavirus infection of pneumonia prevention and control.http://www.hubei.gov.cn/xxgk/gsgg/202001/t20200122_2013895.shtml [Google Scholar]

- Imai N., Dorigatti I., Cori A., Riley S., Ferguson N.M. Preprint published by the Imperial College London; China: 2020. Estimating the potential total number of novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) cases in Wuhan City.https://www.imperial.ac.uk/mrc-global-infectious-disease-analysis/news--wuhan-coronavirus/ [Google Scholar]

- Leung K., Wu J.T., Leung G.M. Preprint published by the School of Public Health of the University of Hong Kong; 2020. Nowcasting and forecasting the Wuhan 2019-nCoV outbreak.https://files.sph.hku.hk/download/wuhan_exportation_preprint.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q., Chiu A.P., Zhao S., He D. Modeling the spread of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Saudi Arabia. Stat Methods Med Res. 2018;27(7):1968–1978. doi: 10.1177/0962280217746442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsitch M., Cohen T., Cooper B., Robins J.M., Ma S., James L. Transmission dynamics and control of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science. 2003;300(5627):1966–1970. doi: 10.1126/science.1086616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China . 2020. ‘Definition of suspected cases of unexplained pneumonia’, the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China (in Chinese)http://www.nhc.gov.cn/ [Google Scholar]

- Read J.M., Bridgen J.R., Cummings D.A., Ho A., Jewell C.P. Novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV: early estimation of epidemiological parameters and epidemic predictions. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2020.0265. 2020.2001.2023.20018549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riou J., Althaus C.L. Pattern of early human-to-human transmission of Wuhan 2019-nCoV. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.4.2000058. 2020.2001.2023.917351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen M., Peng Z., Xiao Y., Zhang L. Modelling the epidemic trend of the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in China. bioRxiv. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1016/j.xinn.2020.100048. 2001.2023.916726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallinga J., Lipsitch M. How generation intervals shape the relationship between growth rates and reproductive numbers. Proc R Soc B: Biolo Sci. 2007;274(1609):599–604. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallinga J., Teunis P. Different epidemic curves for severe acute respiratory syndrome reveal similar impacts of control measures. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(6):509–516. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020. ‘Pneumonia of unknown cause – China’, Emergencies preparedness, response, Disease outbreak news, World Health Organization (WHO)https://www.who.int/csr/don/05-january-2020-pneumonia-of-unkown-cause-china/en/ [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020. Laboratory testing for 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in suspected human cases, World Health Organization (WHO)https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus/laboratory-diagnostics-for-novel-coronavirus [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.T., Cowling B.J., Lau E.H., Ip D.K., Ho L.-M., Tsang T. School closure and mitigation of pandemic (H1N1) 2009, Hong Kong. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16(3):538. doi: 10.3201/eid1603.091216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuhan Municipal Health Commission, China . 2020. ‘News press and situation reports of the pneumonia caused by novel coronavirus’, from December 31, 2019 to January 21, 2020 released by the Wuhan municipal health commission, China.http://wjw.wuhan.gov.cn/front/web/list2nd/no/710 [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S., Musa S.S., Fu H., He D., Qin J. Simple framework for real-time forecast in a data-limited situation: the Zika virus (ZIKV) outbreaks in Brazil from 2015 to 2016 as an example. Parasites Vectors. 2019;12(1):344. doi: 10.1186/s13071-019-3602-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data and materials used in this work were publicly available.