Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) is a novel coronavirus that causes a highly contagious respiratory disease, SARS, with significant mortality. Although factors contributing to the highly pathogenic nature of SARS-CoV remain poorly understood, it has been reported that SARS-CoV infection does not induce type I interferons (IFNs) in cell culture. However, it is uncertain whether SARS-CoV evades host detection or has evolved mechanisms to counteract innate host defenses. We show here that infection of SARS-CoV triggers a weak IFN response in cultured human lung/bronchial epithelial cells without inducing the phosphorylation of IFN-regulatory factor 3 (IRF-3), a latent cellular transcription factor that is pivotal for type I IFN synthesis. Furthermore, SARS-CoV infection blocked the induction of IFN antiviral activity and the up-regulation of protein expression of a subset of IFN-stimulated genes triggered by double-stranded RNA or an unrelated paramyxovirus. In searching for a SARS-CoV protein capable of counteracting innate immunity, we identified the papain-like protease (PLpro) domain as a potent IFN antagonist. The inhibition of the IFN response does not require the protease activity of PLpro. Rather, PLpro interacts with IRF-3 and inhibits the phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of IRF-3, thereby disrupting the activation of type I IFN responses through either Toll-like receptor 3 or retinoic acid-inducible gene I/melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 pathways. Our data suggest that regulation of IRF-3-dependent innate antiviral defenses by PLpro may contribute to the establishment of SARS-CoV infection.

Upon virus infection, the host immediately launches an innate immune defense mechanism characterized by production of type I interferons (IFN2 -α and -β). IFN induces the expression of hundreds of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) that establish an antiviral state, thereby limiting viral replication and spread (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). This innate antiviral response is initiated upon host detection of viral pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) via a number of cellular pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). Viral nucleic acids comprising viral genomes or generated during viral replication present major PAMPs that can be recognized by two different classes of PRRs, i.e. the membrane-bound Toll-like receptors (TLRs) or the caspase recruitment domain-containing, cytoplasmic RNA helicases, retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I), or melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5) (6, 7, 8). Among these, TLR3 and MDA5 detect viral double-stranded (ds) RNA in the endosomes and cytoplasm, respectively (9, 10, 11). Intracellular viral RNAs bearing 5′-triphosphates are recognized by RIG-I (12, 13). Upon engagement of their respective ligands, these PRRs recruit different adaptor molecules, relaying signals to downstream kinases that activate IFN regulatory factor-3 (IRF-3), nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), and ATF/C-Jun, transcription factors that coordinately regulate IFN-β transcription (1, 7). IRF-3 is a constitutively expressed, latent transcription factor that plays a pivotal role in type I IFN responses. Its activation requires specific C-terminal phosphorylation mediated by two noncanonical IκB kinases, TBK1 or IKKε (14, 15). Phosphorylation of IRF-3 leads to its homodimerization, nuclear translocation, and association with CBP/p300, whereupon it collaborates with activated NF-κB to induce IFN-β synthesis (16, 17). In addition, although it is not utilized by most parenchymal cell types, TLR7 constitutes the major pathway in plasmacytoid dendritic cells and triggers potent IFN-α production in circulation upon engagement of single-stranded viral RNAs (18, 19). During co-evolution with their hosts, many viruses have acquired mechanisms to circumvent cellular IFN responses by encoding proteins that disrupt the IFN signaling pathways. It is thought that the early virus-host interactions may significantly impact the course and/or outcome of the infection (1, 5).

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) is a novel coronavirus that causes a highly contagious respiratory disease, SARS, with a significant mortality rate of about 10% (20). The first 3/4 of the positive-sense, single-stranded, 29.7-kb genome of SARS-CoV is translated into two large replicase polyproteins (22, 23, 24) called as pp1a and pp1ab (25, 26). Papain-like protease (PLpro) and 3C-like protease domains present within these polyproteins direct their processing into 16 nonstructural proteins (nsp1-16) that assemble to generate a multifunctional, membrane-associated replicase complex. Unlike other coronaviruses that encode two different PLpros, SARS-CoV encodes only one. Residing within the 213-kDa, membrane-associated replicase product nsp3, the SARS-CoV PLpro is responsible for cleaving junctions spanning nsp1 to nsp4 (27). Surprisingly, the crystal structure of SARS-CoV PLpro resembles that of known cellular deubiquitinating (DUB) enzymes USP14 and HAUSP (28). SARS-CoV PLpro has also been demonstrated to have both DUB and deISGylation activities in vitro, consistent with the fact that it shares the consensus recognition motif LXGG with cellular DUBs (29, 30). Based on these findings, it has been proposed that SARS-CoV PLpro may have important but still uncharacterized functions in regulating cellular processes, in addition to its role as a viral protease (29, 30).

Although factors contributing to the highly pathogenic nature of SARS-CoV remain poorly understood, infection of HEK293 cells does not induce production of type I IFNs (21). However, pretreatment of permissive cells with IFN prevents SARS-CoV replication (31). These are intriguing observations, as the ability to disrupt IFN responses seems to correlate with in vivo virulence in some viral infections, e.g. equine, swine, and H5N1 avian influenza viruses which express NS1, a well characterized IFN antagonist (32, 33, 34). The absence of IRF-3 activation and IFN-β mRNA induction in SARS-CoV-infected HEK293 cells has led to the proposal that SARS-CoV is able to disrupt the activation of IRF-3-mediated defenses (21). However, contradictory results have been published regarding whether SARS-CoV evades host detection or, alternatively, has developed strategies to actively block host innate defense mechanisms. Three SARS-CoV proteins, ORF3b, ORF6, and nucleocapsid (N), were recently identified as IFN antagonists, based on their ability to inhibit IRF-3 activation (35). SARS-CoV nsp1 was also shown to inhibit host IFN responses by inducing the degradation of host mRNAs (36). However, others have reported that infection of mouse hepatitis virus, a closely related type 2 coronavirus, or SARS-CoV does not activate IFN-β synthesis in murine fibroblasts nor inhibit its induction by poly(I-C) or Sendai virus (SeV) (37, 38). It was proposed from these studies that group 2 coronaviruses are “invisible” to host cells and thus avoid innate immunity by somehow avoiding host recognition (37, 38).

Here we show that SARS-CoV triggers a weak, yet demonstrable IFN response in cultured human lung/bronchial epithelial cells and fibroblasts derived from fetal rhesus monkey kidney, both of which are naturally permissive to SARS-CoV. Furthermore, SARS-CoV infection blocks the induction of IFN antiviral activity and the up-regulation of a subset of ISG proteins in response to dsRNA or SeV. We also identify the PLpro of SARS-CoV as a potent IFN antagonist. PLpro interacts with IRF-3 and inhibits its phosphorylation and nuclear translocation, thereby disrupting multiple signaling pathways leading to IFN induction. Finally, we demonstrate a role of IRF-3 signaling in control of SARS-CoV infection by showing that disruption of IRF-3 function significantly up-regulates SARS-CoV replication. Our data suggest that SARS-CoV is detected by the innate immune surveillance mechanism of host cells, but that active regulation of IRF-3-mediated host defenses limits the IFN responses and likely contributes to establishment of SARS-CoV infection.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells—Human bronchial epithelial cells Calu-3, African green monkey kidney cells MA104 and Vero, human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293, 293T, 293-TLR3 (a gift from Kate Fitzgerald), HeLa, and human hepatoma cells Huh7 were maintained by conventional techniques. HeLa Tet-Off cell lines (Clontech) were cultured following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Plasmids—To obtain high level expression of SARS-CoV PLpro in eukaryotic cells, the codon usage of the SARS-CoV PLpro core domain (amino acids 1541-1855 of pp1a of SARS-CoV Urbani strain, GenBank™ accession number AY278741) was optimized based on the human codon usage frequency, and the potential splicing sites and polyadenylation signal sequences were removed from the coding regions of PLpro. The optimized PLpro was named SARS PLpro Sol (Supplemental Material) and cloned into pcDNA3.1-V5/HisB (Invitrogen) between the BamHI and EcoRI sites with in-frame fusion with C-terminal V5 and His6 tags, to result in the expression plasmid pCDNA3.1-SARS-PLpro-Sol. To generate pCDNA3.1-SARS-PLpro-TM (amino acids 1841-2425), the coding sequence for the TM domains downstream of PLpro in SARS-CoV nsp3 was amplified from the plasmid pPLpro-HD (27) by PCR with primers P1, 5′-TTAGAATTCACCTGTGTCGTAACTC-3′, and P2, 5′-TAACTCGAGGTGAGTCTTGCAGAAGC-3′, and the product was digested with EcoRI/XhoI and cloned downstream of PLpro Sol with C-terminal in-frame fusion of V5-His6 tags. The catalytically inactive mutants of PLpro Sol and PLpro-TM (C1651A and D1826A) were generated by QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene) using specific primers containing the desired mutations (Supplemental Material). The fidelity of the cDNA inserts in all constructs was validated by DNA sequencing. To construct a tetracycline (tet)-regulated expression plasmid for SARS-CoV PLpro-TM, cDNA fragment encoding PLpro-TM along with its downstream V5-His6 tags in pCDNA3.1-SARS-PLpro-TM were excised by restriction digestion with HindIII and PmeI, and ligated into pTRE2Bla (39) that was digested with HindIII and EcoRV, to result in the plasmid pTRE2Bla-SARS-PLpro-TM. To construct a tet-regulated expression plasmid for a dominant negative (DN) form of IRF-3, cDNA encoding the amino acids 134-427 of IRF-3 was amplified from Huh7 cDNA by PCR and cloned into pTRE2Bla (39) between HindIII and XbaI sites, to generate pTRE2Bla-IRF3DN133.

The cDNA expression plasmids for TRIF, RIG-I, MAVS, and bovine viral diarrhea virus Npro have been described (39, 40, 41, 43). The following plasmids were kind gifts from the respectively indicated contributors: pCDNA3-A20-myc (from Nancy Raab-Traub) (42); p55C1Bluc, pEFBos N-RIG, and pEFBos N-MDA5 (from Takashi Fujita) (6); pcDNA3-FLAG TBK1 and pcDNA3-FLAG IKKε (from Kate Fitzgerald) (15); pIFN-β-luc. IRF3-5D, GFP-IRF3, and GFP-IRF3 5D (from Rongtuan Lin) (17); PRDII-Luc (from Michael Gale), and (PRDIII-I)4-Luc (from Christina Ehrhardt) (44).

Generation of Tet-regulated Cell Lines—The detailed procedures for establishment of HeLa- and Huh7-inducible cells were similar to those described previously (39, 45). Briefly, to generate HeLa PLpro-inducible cells, HeLa Tet-Off cells were transfected with pTRE2Bla-SARS-PLpro-TM using FuGENE 6 (Roche Applied Science) and double-selected in complete medium supplemented with 100 μg/ml G418, 1 μg/ml blasticidin, and 2 μg/ml Tet. Approximately 3 weeks later, individual cell colonies were selected, expanded, and examined for SARS-CoV PLpro-TM expression by indirect immunofluorescence staining using a mouse monoclonal antibody (mAb) against the V5 epitope (Invitrogen) (1:500) that is present at the C terminus of PLpro-TM, after being cultured in the absence of tet for 4 days. Two independent cell clones, designated HeLa PLpro-4 and -10, respectively, allowed tight regulation of PLpro-TM expression under tet control and were selected for further characterization. Inducible expression of PLpro-TM in these cells was also confirmed by immunoblot analysis using both the V5-tag mAb and a rabbit antiserum against SARS-CoV nsp3 (27). To generate Huh7 cells with conditional expression of DN-IRF-3, cells were cotransfected with pTet-Off (Clontech) and pTRE2Bla-IRF3DN133 at a ratio of 1:10, and double-selected in complete medium supplemented with 400 μg/ml G418, 2 μg/ml blasticidin, and 2 μg/ml tet. Expansion and screening of positive clones were conducted by procedures similar to those used for HeLa PLpro-inducible cells, except that a rabbit polyclonal IRF-3 antiserum (kindly provided by Michael David) was used for immunostaining and immunoblot analysis. Three individual cell clones, designated Huh7 DN-6, -12, and -18, respectively, allowed tightly regulated expression of DN-IRF3 at various levels. However, under fully induced conditions (-tet), only DN-18 cells expressed DN-IRF-3 at a level higher than that of the endogenous IRF-3, and thus allowed a demonstrable DN effect on viral induction of IRF-3 target genes (Fig. 9A and data not shown). Therefore, we selected DN-18 cells for further analysis.

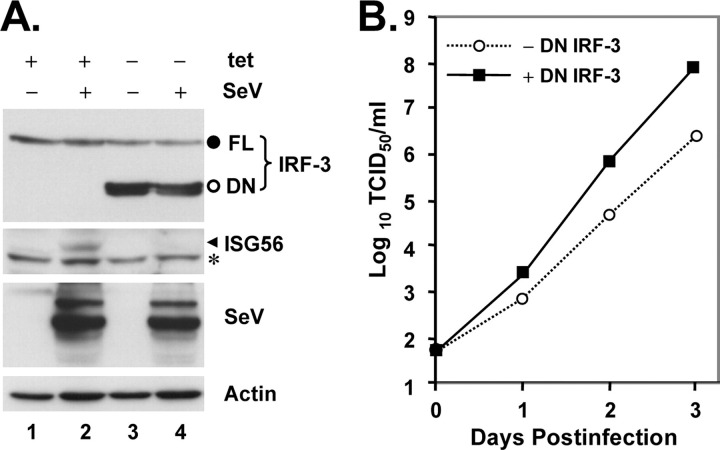

FIGURE 9.

The IRF-3 pathway regulates SARS-CoV replication in cell culture.A, Huh7 DN-18 cells with tet-regulated, conditional expression of a dominant negative form of IRF-3 (DN IRF-3) were cultured in the presence or absence of tet for 3 days, to repress or induce DN IRF-3 expression, respectively, and were subsequently mock-infected or challenged with SeV for 12 h. Expression of IRF-3, ISG56, SeV, and actin proteins were detected in cell lysates by immunoblot analysis. The endogenous IRF-3 (FL) and the DN IRF-3 (DN) bands were marked as filled and empty circles, respectively. The asterisk in the ISG56 panel denotes a nonspecific band. B, Huh7 DN-18 cells repressed or induced for DN IRF-3 expression were infected with SARS-CoV at an m.o.i. of 0.01 at 37 °C for 1 h. The virus inoculum was then removed, and cells were washed extensively and refed with complete medium. Cell-free culture supernatants were collected at the indicated times postinfection and stored at -80 °C until they were subjected to assessment of infectious viral titers using a standard TCID50 assay in Vero E6 cells, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The experiments were terminated at day 3 postinfection as CPE was observed in ∼30 and ∼70% of infected cells without and with DN IRF-3 expression, respectively. The growth curve of SARS-CoV shown was representative of three independently conducted experiments.

SeV Infection and Poly(I-C) Treatment—Where indicated, cells were infected with 100 hemagglutinin units (HAU)/ml of SeV (Cantell strain, Charles River Laboratories) for 8-16 h prior to cell lysis for luciferase/β-galactosidase reporter assays and/or immunoprecipitation/immunoblot analysis as described previously (39, 40, 41, 46). For poly(I-C) treatment, poly(I-C) (Sigma) was added directly to the culture medium at 50 μg/ml (M-pIC) or complexed with Lipofectamine 2000 (at 1:1 ratio) (T-pIC) and loaded onto the cells for the indicated time period.

SARS-CoV Infection and Titration—Where indicated, cells were infected with the Urbani strain of SARS-CoV (kindly provided by T. G. Ksiazek, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA) at the indicated m.o.i. as described previously (47). The cell-free SARS-CoV stock with a titer of 1 × 107 TCID50/ml (50% tissue culture infectious dose) was generated following two passages of the original stock in Vero E6 cells and stored in aliquots at -80 °C. All experiments involving infectious viruses were conducted in an approved biosafety level 3 laboratory at the University of Texas Medical Branch. The infectious viral titers in the cell-free supernatants collected at different time points postinfection were determined by a standard TCID50 assay on permissive Vero E6 cell monolayers in 96-well plates with a series of 10-fold-diluted samples. The titer was expressed as TCID50 per ml of individual samples.

IFN Bioactivity Assay—IFN bioactivity in γ-irradiated cell culture supernatants was determined by a standard microtiter plaque reduction assay using vesicular stomatitis virus on Vero cells, as described previously (48).

Transfection and Reporter Gene Assay—Cells grown in 24-well plates (5 × 104/well) were transfected in triplicate with the indicated reporter plasmid (100 ng), pCMVβgal (100 ng), and the indicated amount of an expression vector (50-400 ng and supplied with an empty vector to keep the total amount of DNA transfected constant) using FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science), as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Twenty four hours later, transfected cells were mock-treated, treated with poly(I-C) for 6 h, or infected with SeV for 16 h before cell lysis and assay for both firefly luciferase and β-galactosidase activities. Data were expressed as mean relative luciferase activity (luciferase activity divided by β-galactosidase activity) with standard deviation from a representative experiment carried out in triplicate. A minimum of three independent experiments were performed to confirm the results of each experiment. The fold change of promoter activity was calculated by dividing the relative luciferase activity of stimulated cells by that of mock-treated cells.

Indirect Immunofluorescence Staining—Cells grown in chamber slides (LabTek) following the indicated treatments were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were then permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min and blocked in 3% bovine serum albumin at room temperature for 30 min. After a PBS rinse, the slides were incubated with a rabbit polyclonal antiserum against human IRF3 (1:500, kindly provided by Michael David) (49), or with a V5 tag mAb (1:500, Invitrogen), or with a rabbit polyclonal antiserum (R3) against SARS-CoV nsp3 (27) (1:1000) in 3% BSA for 1 h at room temperature. Following three washings in PBS, slides were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate or Texas Red-conjugated, goat anti-rabbit, or goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibodies (Southern Biotech) at 37 °C for 30 min. Slides were washed, mounted in Vectashield mounting medium containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, to view the nuclei) (Vector Laboratories), and sealed with a coverslip. Stained slides were examined under a Zeiss Axioplan II fluorescence microscope or an LSM-510 META laser scanning confocal microscope in the University of Texas Medical Branch Optimal Imaging Core. For calculation of the percentage of cells demonstrating IRF-3 nuclear translocation, the numbers of cells showing IRF-3 nuclear translocation were counted in 4 random fields at ×20 magnification and/or 10 random fields at ×40 magnification and divided by the total numbers of cells (DAPI-positive) in the total counted fields.

RT-PCR—Following the indicated treatments/viral infections, total cellular RNA was extracted from Calu-3, MA104, or HeLa PLpro-inducible cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), treated with DNase I to remove genomic DNA contamination, and subjected to clean up using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). The abundance of cellular mRNAs specific to human IFN-β, IL-6, and A20 genes was determined by quantitative real time RT-PCR (q-RT-PCR) using commercially available primers and Taqman probes (Applied Biosystems) at the University of Texas Medical Branch Sealy Center for Cancer Cell Biology Real Time PCR Core. We confirmed that the human IFN-β primers and TaqMan probe worked well for MA104 cells of green monkey kidney origin. In some experiments, semiquantitative RT-PCR was also used to compare the mRNA abundance of IFN-β, ISG56, and IL-6 and that of viral RNAs, SeV (Cantell strain), and SARS-CoV (Urbani strain) as described previously (40). The following forward and reverse primers were used: IFN-β (works for both human and rhesus monkey); IFN-B con107+, tcctgttgtgcttctccac, and IFN-B con383-, gtctcattccagccagtgct. The primers for ISG56 (works for both human and rhesus monkey) (40) and IL-6 (human) (50) have been described. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase primers were purchased from Clontech. For semiquantitative detection of viral RNAs, the following primers were used: SARS CoV, described in Ref. 51; SeV; SeV P890+, aatagggacccgctctgtct; and SeV P1226-, ttccacgctctcttggatct.

Phosphatase Inhibitor Treatment—For in vivo experiments, HeLa PLpro-4 cells repressed or induced for PLpro expression or HeLa cells were mock-infected or infected with SeV for 12 h, followed by an additional 4-h incubation with or without 0.05 μg/ml of okadaic acid (OA) (Calbiochem) prior to cell lysis and immunoblot analysis. For in vitro experiments, 40 μg of whole cell lysate of HeLa cells infected with SeV were mock-treated or incubated with 5 units of calf intestine alkaline phosphatase (CIP, New England Biolabs) in CIP buffer, or incubated with 0.05 μg/ml of OA, or treated with CIP in the presence of OA, respectively, at 30 °C for 2 h.

Protein Analyses—Cellular extracts were prepared and subjected to immunoblot analysis and/or immunoprecipitation as described previously (39, 40, 41). The following mAbs or polyclonal (pAb) antibodies were used: anti-FLAG M2 mAb and pAb and anti-actin mAb (Sigma); anti-V5 mAb (Invitrogen); anti-GFP mAb (Roche Applied Science); anti-IRF-3 mAb and rabbit anti-CBP pAb (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); rabbit anti-IRF-3 pAb (from Michael David); rabbit anti-IRF-3-p396 pAb (from John Hiscott); rabbit anti-RIG-I pAb (from Zhijian Chen); rabbit anti-ISG56 pAb (from Ganes Sen); rabbit anti-MxA and anti-Sendai virus pAbs (from Ilkka Julkunen); rabbit anti-SARS-CoV N pAb (Imgenex); rabbit anti-SARS-CoV nsp3 pAb (27); peroxidase-conjugated secondary goat anti-rabbit, and goat anti-mouse pAbs (Southern Biotech). Protein bands were visualized using ECL plus Western blotting detection reagents (GE Healthcare), followed by exposure to x-ray film. For detection of IRF-3 dimer, native PAGE of protein samples was performed as described previously (52).

RESULTS

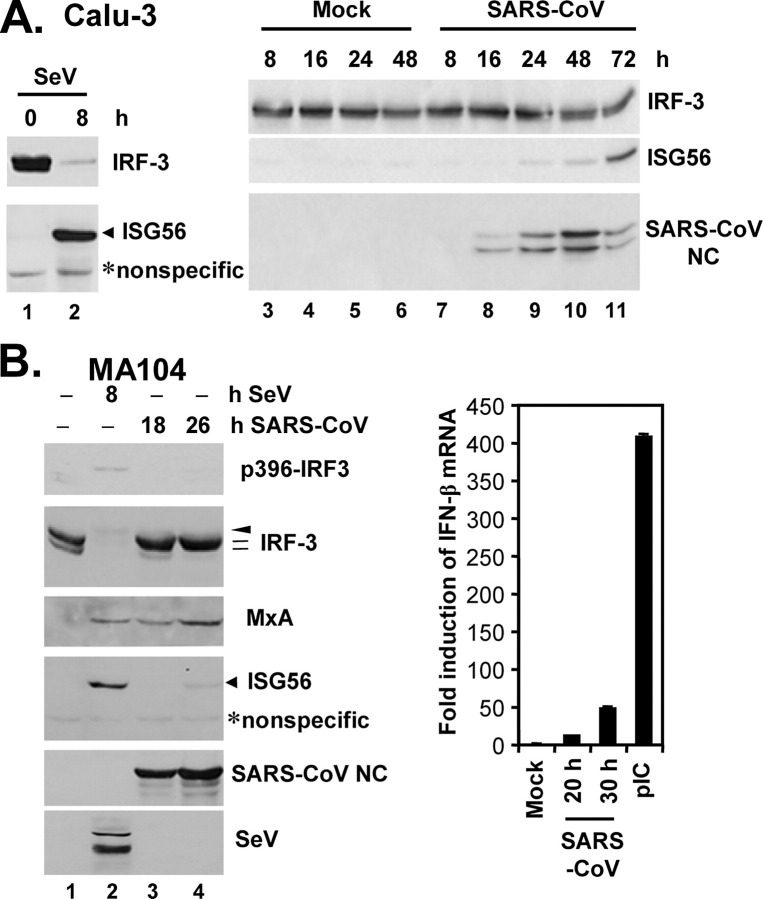

SARS-CoV Weakly Activates an IFN Response in Cultured Cells without Inducing the Phosphorylation of IRF-3—To investigate whether SARS-CoV triggers an IFN response in cell culture, we determined the cellular responses to infection with the Urbani strain of SARS-CoV in a human lung/bronchial epithelial cell line, Calu-3, which serves as an excellent in vitro culture model for studying the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV in the respiratory system (47). As a control, cells were also infected with SeV, a paramyxovirus that is a well characterized inducer of IFN production via the RIG-I pathway (6, 40). In Calu-3 cells, SeV infection rapidly triggered phosphorylation and degradation of IRF-3, which was accompanied by potent induction of ISG56, a well characterized IRF-3 target gene (53, 54) (Fig. 1A , left panel, compare lanes 2 versus 1). However, infection of Calu-3 cells with SARS-CoV did not induce detectable phosphorylation or degradation of IRF-3. Nonetheless, there was a weak, yet reproducible induction of ISG56 expression, starting 24 h postinfection and peaking at 72 h (Fig. 1A , right panels). The weak induction of an IFN response by SARS-CoV in Calu-3 cells was also confirmed by q-RT-PCR analysis of IFN-β mRNA (data not shown). To ensure that these findings generally reflect SARS-CoV infection and were not a cell-type specific phenomenon, we conducted similar experiments in an African green monkey kidney cell line MA104. These cells have been reported to be permissive for SARS-CoV infection (55), and we have found that MA104 cells supported SARS-CoV replication with faster kinetics than Calu-3 cells, with cytopathic effect (CPE) seen as early as 28 h postinfection.3 In contrast to another African green monkey kidney cell line, Vero, which is widely used for in vitro propagation of SARS-CoV and defective in IFN synthesis (56), MA104 cells are IFN-competent (57). We found that infection of MA104 cells with SARS-CoV up-regulated IFN-β mRNA by 12- and 49-fold, respectively, at 20 and 30 h postinfection, although the induction of IFN mRNA was significantly weaker than that (409-fold) triggered by transfection of a synthetic dsRNA analog, poly(I-C) (Fig. 1B , right panel). Immunoblot analysis (Fig. 1B , left panels) demonstrated that SeV triggered the phosphorylation and degradation of IRF-3 in MA104 cells early after infection (8 h), accompanied by the appearance of serine 396-phosphorylated species of IRF-3 (p396-IRF3). However, because of the proteasomal degradation of IRF-3 (17), the abundance of p396-IRF3 detected in SeV-infected MA104 cells was markedly reduced when compared with that induced by transfected poly(I-C) (supplemental Fig. 1, compare lane 5 versus 3). The weak band reacted with p396-IRF3 antibody was not IRF-7, which is not basally expressed in MA104 cells and only minimally induced during this short infection period (8 h), and has a higher molecular weight than that of p396-IRF-3 (supplemental Fig. 1). SeV also significantly induced the expression of ISG56, as well as MxA, an ISG whose expression is dependent on functional JAK-STAT signaling downstream of the IFN receptor (58). In contrast, SARS-CoV did not induce the phosphorylation or degradation of IRF-3, nor did it trigger IRF-3 phosphorylation at Ser396 site in MA104 cells during the observation period (18 and 28 h, respectively) (Fig. 1B , left panels). Nonetheless, we reproducibly observed that SARS-CoV infection of MA104 cells induced a shift in the two IRF-3 basal forms from the lower to the higher mass form, a phenomenon that is more evident late after SARS-CoV infection (26 h) (Fig. 1B , IRF-3 panel, compare lane 4 versus 1). This is reminiscent of HSV-1-infected A549 cells (59). Furthermore, there was a weak induction of ISG56 protein expression at 26 h postinfection (Fig. 1B , lane 4). Interestingly, despite these findings, induction of MxA occurred early (at 18 h postinfection) and increased with time (Fig. 1B , MxA panel, lanes 3 and 4) in SARS-CoV infected MA104 cells. Collectively, these data suggest that SARS-CoV is recognized by host cells of lung epithelium and kidney origin and able to elicit a weak IFN response, although this does not involve demonstrable phosphorylation and degradation of IRF-3. We conclude that SARS-CoV is subject to the surveillance of cellular innate immunity; however, as reported previously (21), SARS-CoV has likely evolved strategies to evade or counteract these protective host responses.

FIGURE 1.

SARS-CoV weakly activates an IFN response without inducing the hyperphosphorylation of IRF-3.A, human lung/bronchial epithelial Calu-3 cells were mock-infected or infected with 100 HAU/ml SeV (left panels) or SARS-CoV (right panels) at an m.o.i. of 5 for the indicated times prior to cell lysis and immunoblot analysis of IRF-3, ISG56, and SARS-CoV nucleocapsid (NC) protein. B, left panels show African green monkey kidney MA104 cells that were mock-infected or infected with SeV (100 HAU/ml) or with SARS-CoV (m.o.i. = 10) for the indicated times prior to cell lysis and immunoblot analysis of phospho-Ser396 IRF-3, total IRF-3, MxA, ISG56, SARS-CoV NC, and SeV proteins. A nonspecific band (*) detected by the anti-ISG56 antibody indicates equal loading. The arrowhead and hatch marks in the total IRF-3 panel denote phosphorylated (virus-activated) and inactive IRF-3 forms, respectively. In the right panel, MA104 cells grown in 35-mm dishes were mock-treated, infected with SARS-CoV (m.o.i. = 10) for 20 or 30 h, or transfected with 5 μg of poly(I-C) for 10 h prior to total RNA extraction and real time RT-PCR analysis of IFN-β mRNA abundance, which was subsequently normalized to cellular 18 S ribosomal RNA. Bars show fold change in IFN-β mRNA levels (relative to mock-treated cells).

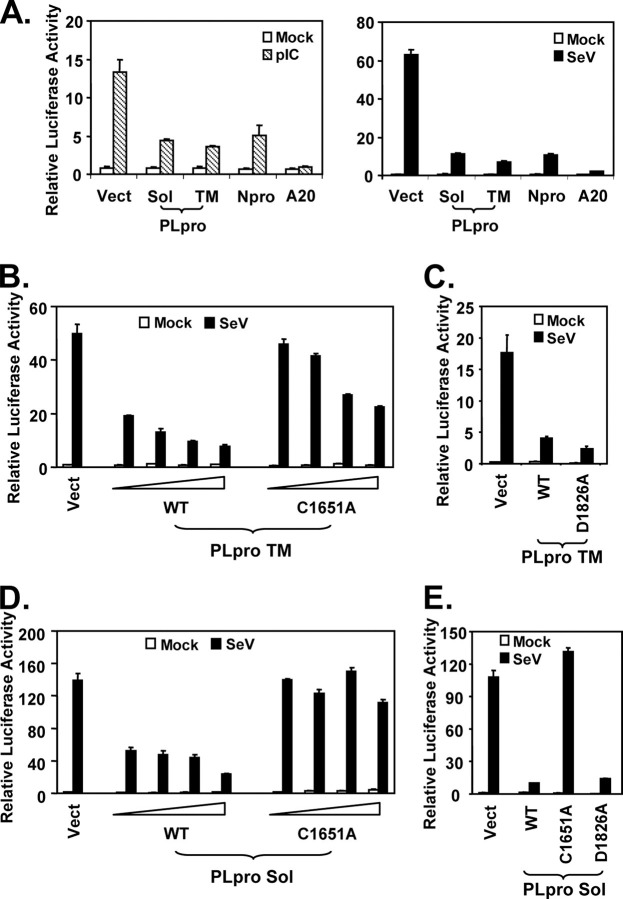

The PLpro Domain of SARS-CoV Inhibits Activation of IFN-β Promoter following Engagement of TLR3 or RIG-I Pathways Independent of Its Protease Activity—In searching for SARS-CoV protein(s) that inhibit IFN responses, the PLpro domain of SARS-CoV nsp3 caught our attention. In addition to its role in directing the processing of viral polyproteins, SARS-CoV PLpro was recently shown to have deubiquitination activity (29, 30). As ubiquitination plays a pivotal role in many cellular processes, including innate immunity signaling (60, 61), we conducted experiments to determine whether SARS-CoV PLpro could regulate induction of cellular IFN responses. Engagement of the TLR3 pathway by addition of the synthetic dsRNA analog, poly(I-C), to culture medium of HEK293 cells that stably express TLR3 (293-TLR3), induced the IFN-β promoter by 16-fold. However, poly(I-C)-induced IFN-β promoter activity was reduced by 70% in cells ectopically expressing the catalytic core domain of SARS-CoV PLpro (Sol) or PLpro-TM that encodes PLpro-Sol in conjunction with its downstream hydrophobic transmembrane domains (Fig. 2A , left panel). Similar inhibition of the activation of IFN-β promoter by PLpro-Sol and PLpro-TM was observed when IFN response was triggered by SeV, which activates the RIG-I pathway (6, 11, 40) (Fig. 2A , right panel). As positive controls, ectopic expression of known viral or mammalian inhibitors of the IFN response, i.e. the papain-like protease of bovine viral diarrhea virus, Npro (43), or a human deubiquitination enzyme, A20 (62), respectively, also strongly suppressed activation of the IFN-β promoter by poly(I-C) or SeV (Fig. 2A , left and right panels). Thus, these data suggest that expression of the catalytic core domain of SARS-CoV PLpro is sufficient for inhibiting activation of the IFN-β promoter via both TLR3 and RIG-I pathways.

FIGURE 2.

SARS-CoV PLpro domain inhibits activation of IFN-β promoter following engagement of TLR3 or RIG-I pathways independent of its protease activity.A, HEK293-TLR3 cells were co-transfected with pIFN-β-Luc and pCMVβgal plasmids and a vector (Vect) encoding SARS PLpro-Sol (Sol) or SARS PLpro-TM (TM), bovine viral diarrhea virus Npro, or A20, or an empty vector. Twenty four hours later, cells were either mock-treated (empty bars) or incubated with 50 μg/ml poly(I-C) in culture medium for 6 h (hatched bars, left panel), or infected with SeV at 100 HAU/ml for 16 h (solid bars, right panel) prior to cell lysis for both luciferase and β-galactosidase assays. Bars show relative luciferase activity normalized to β-galactosidase activity, i.e. IFN-β promoter activity. B and C, IFN-β promoter activity in cells transfected with increasing amounts of WT or C1651A mutant PLpro-TM-expressing plasmid (B) or equivalent amounts of WT or D1826A mutant PLpro-TM plasmid (C). D and E, IFN-β promoter activity in cells transfected with increasing amounts of WT or C1651A mutant PLpro-Sol-expressing plasmid (D) or equivalent amounts of WT, C1651A, or D1826A mutant PLpro Sol plasmids (E).

Next, we determined whether the protease activity of PLpro was required for inhibiting the cellular IFN response, a property that is shared by the NS3/4A serine proteases of two flaviviruses, hepatitis C virus and GB virus B (39, 46), and the 3ABC protease precursor of a picornavirus, hepatitis A virus (63). SARS-CoV PLpro consists of a triad-active site, i.e. Cys1651-His1812-Asp1826. Mutation at any of the three sites is known to abrogate the protease activity of PLpro (29) (supplemental Fig. 2). We found that when PLpro was expressed in conjunction with its downstream hydrophobic transmembrane domain (PLpro-TM) (27), the wild-type, C1651A mutant, and D1826A mutant were all able to inhibit activation of the IFN-β promoter by SeV (Fig. 2, B and C) or poly(I-C) (data not shown). The D1826A mutant PLpro suppressed activation of IFN-β promoter as efficiently as the WT protein, whereas the C1651A mutant was less efficient than wild type but suppressed in a dose-dependent manner. These data suggest that the protease activity of PLpro is not responsible for its inhibition of activation of IFN responses. To further investigate the role of the catalytic residues, we expressed the wild-type and catalytic mutants of PLpro (PLpro-Sol). We found that ectopic expression of the WT PLpro-Sol inhibited the activation of IFN-β promoter by SeV (Fig. 2D) or medium poly(I-C) (data not shown) in a dose-dependent fashion. In addition, the PLpro-Sol D1826A mutant inhibited the IFN response as efficiently as wild-type PLpro-sol (Fig. 2E). However, there was no appreciable effect with overexpression of the related, catalytically inactive C1651A PLpro-Sol mutant. We hypothesize that the C1651A substitution in PLpro-Sol may altering the folding/conformation of the protein in addition to its disruption of the protease active site. Consistent with this hypothesis, we noticed a significant reduction in the yield of PLpro-Sol containing the C1651A mutation when purifying the protein from Escherichia coli (29), presumably as a result of altered protein folding that renders PLpro mutants insoluble in E. coli. Taken collectively, these data show that the PLpro domain of SARS-CoV is capable of antagonizing the induction of IFN-β promoter via both TLR3 and RIG-I pathways, and this occurs independently of the protease activity of PLpro.

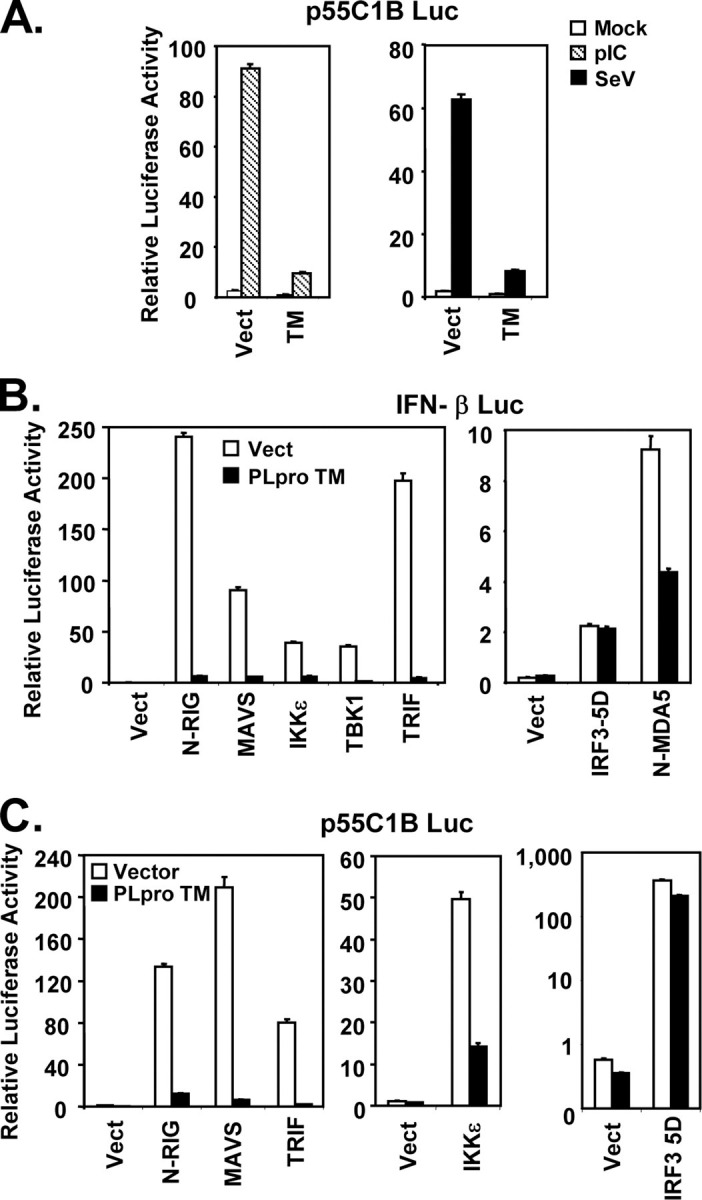

SARS-CoV PLpro Inhibits Induction of IRF-3-dependent Genes by Acting at a Level Downstream of the IRF-3 Kinases and Proximal to IRF-3—The latent cellular transcription factor IRF-3 plays a central role in transcriptional control of the IFN-β promoter (17, 64). To determine whether PLpro inhibition of the IFN-β promoter is related to its suppressive effect on IRF-3 activation, we conducted luciferase reporter assays utilizing an IRF-3-dependent synthetic promoter, 55C1B (6), following poly(I-C) treatment or SeV challenge. As shown in Fig. 3A , we found that activation of 55C1B promoter by either poly(I-C) or SeV was almost completely ablated by ectopic expression of PLpro-TM. Similar results were obtained when another IRF-3-dependent synthetic promoter, PRDIII-I (44), was used in lieu of 55C1B for probing the signaling (data not shown). The two noncanonical IκB kinases, TBK1 and IKKε, mediate the C-terminal phosphorylation of IRF-3, a prerequisite prior to its activation. They are linked to the distinct viral PRRs, RIG-I/MDA5 and TLR3, by the adaptor proteins MAVS and TRIF, respectively (65, 66, 67, 68, 69). To determine the level of the PLpro blockade of IRF-3 activation, we determined the effect of PLpro on induction of IRF-3-dependent promoters, following ectopic expression of signaling proteins known to participate in RIG-I/MDA5 and TLR3 pathways upstream of IRF-3. We found that PLpro-TM strongly inhibited the activation of IFN-β promoter by overexpression of the constitutive active caspase recruitment domain of RIG-I (N-RIG) or MDA5 (N-MDA5) or by ectopic expression of MAVS, TRIF, TBK1, or IKKε (Fig. 3B). In contrast, the constitutively active, phospho-mimetic IRF-3 mutant, IRF-3-5D, activated the IFN-β promoter in cells expressing PLpro-TM to a level that was comparable with that in cells transfected with a control vector (Fig. 3B). Similar results were obtained when p55C1B-Luc was used in place of IFN-β-Luc to probe the signaling (Fig. 3C). We conclude from these experiments that PLpro disrupts TLR3 and RIG-I/MDA5 signaling by acting at a level that is downstream of the IRF-3 kinases and proximal to IRF-3.

FIGURE 3.

SARS-CoV PLpro inhibits activation of IRF-3-dependent promoters by acting at a level downstream of the IRF-3 kinases and proximal to IRF-3.A, activation of p55C1B, an IRF-3-dependent synthetic promoter, by medium poly(I-C) (hatched bars) or SeV infection (solid bars) in HEK293-TLR3 cells with expression of SARS-CoV PLpro-TM (TM) or a control vector (Vect). B and C, activation of IFN-β (B) and p55C1B (C) promoters by ectopic expression of various signaling molecules within TLR3 and RIG-I/MDA5 pathways at or above the level of IRF-3 in HEK293 cells with (solid bars) or without (empty bars) expression of SARS-CoV PLpro-TM. N-RIG and N-MDA5 denote the caspase recruitment domain of RIG-I and MDA5, respectively.

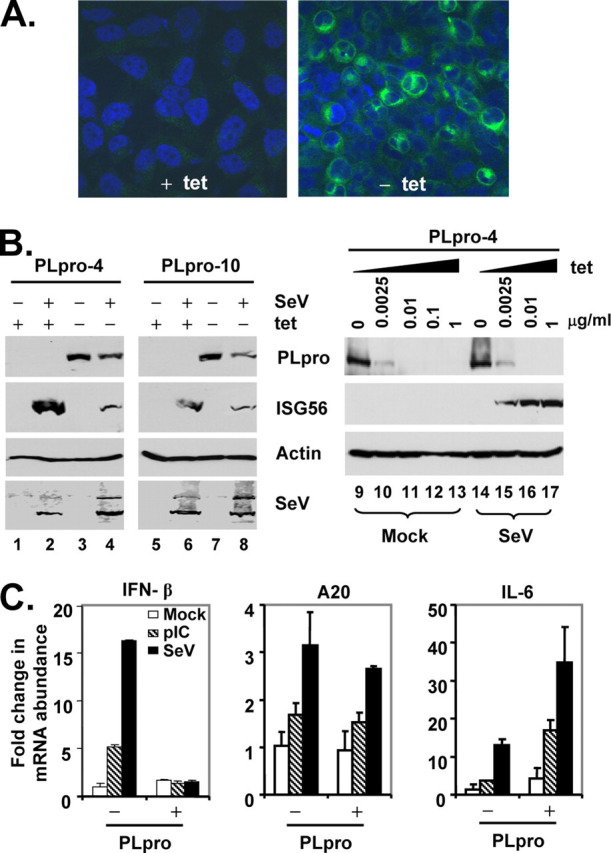

To better characterize the mechanisms underlying the SARS-PLpro disruption of cellular IFN responses, we developed tet-regulated HeLa cells that conditionally express PLpro-TM under the control of the Tet-Off promoter. Two clonal cell lines, designated PLpro-4 and PLpro-10, respectively, were selected for further analysis. In these cells, expression of PLpro-TM was tightly regulated by tet, and it only occurred when tet was removed from the culture medium (Fig. 4, A and B ). The expression level of PLpro-TM could also be conveniently titrated by culturing cells at different concentrations of tet (Fig. 4B , right panels). Under confocal microscopy, PLpro-TM showed a perinuclear, cytoplasmic localization that was similar to that reported for nsp3 in SARS-CoV infected cells (27) (Fig. 4A , right panel). Confirming the data obtained from promoter-based reporter assays (Figs. 2 and 3), we found that de-repression of PLpro-TM expression significantly inhibited the SeV induction of endogenous ISG56 expression in both cell clones (Fig. 4B , left panels), and this inhibitory effect was dose-dependent on the expression level of PLpro-TM (Fig. 4B , right panels). This could not be attributed to inhibition of SeV replication by PLpro, as similar levels of SeV proteins were produced, regardless of PLpro-TM induction status (Fig. 4B , SeV panel). A similar inhibition of poly(I-C)-induced ISG56 expression by PLpro-TM was also observed in these cells, regardless of the delivery route, i.e. poly(I-C) being added to culture medium or introduced into cells by transfection, which engage the TLR3 and MDA5 pathways (10, 11), respectively (Fig. 5A , ISG56 panel, compare lane 6 versus 2, and data not shown). Real time RT-PCR analysis showed that PLpro-TM expression ablated the up-regulation of IFN-β mRNA by poly(I-C) or SeV challenge, while leaving the induction of the NF-κB-dependent A20 mRNA transcripts intact (70) (Fig. 4C , left and central panels). Furthermore, PLpro-TM potentiated the induction of IL-6 mRNA by poly(I-C) or SeV (Fig. 4C , right panel). Taken collectively, these data suggest that SARS-CoV PLpro specifically targets the IRF-3 arm of IFN responses for inhibition.

FIGURE 4.

Conditional expression of SARS-CoV PLpro-TM disrupts endogenous, IRF-3-dependent gene expression following dsRNA stimulation or SeV infection.A, immunofluorescence staining of PLpro-TM in HeLa PLpro-4 cells cultured in the presence (left) or absence (right) of 2 μg/ml tetracycline for 3 days followed by confocal microscopy. PLpro-TM showed green fluorescence staining (detected with a V5 tag antibody), whereas nuclei were counterstained blue with DAPI. B, left panels show HeLa PLpro-4 and PLpro-10 cells that were cultured with and without tetracycline for 3 days and subsequently mock-infected or challenged with SeV for 16 h prior to cell lysis and immunoblot blot analysis of PLpro (using a V5 tag antibody), ISG56, actin, and SeV. The right panels show HeLa PLpro-4 cells that were cultured in the indicated concentrations of tetracycline for 3 days prior to mock infection (lanes 9-13) or infection of SeV (lanes 14-17) for 16 h. Expression of PLpro-TM, ISG56, and actin were determined by immunoblot analysis. C, real time RT-PCR analysis of IFN-β (left), A20 (middle), and IL-6 (right) mRNA transcripts in HeLa PLpro-4 cells repressed or induced for PLpro-TM expression, and mock-treated (empty bars), treated with 50 μg/ml poly(I-C) in culture medium (hatched bars), or infected with SeV (solid bars) for 16 h. mRNA abundance was normalized to cellular 18 S ribosomal RNA. Fold changes were calculated by dividing the normalized mRNA abundance under various treatment conditions by that of the mock-treated cells without PLpro expression.

FIGURE 5.

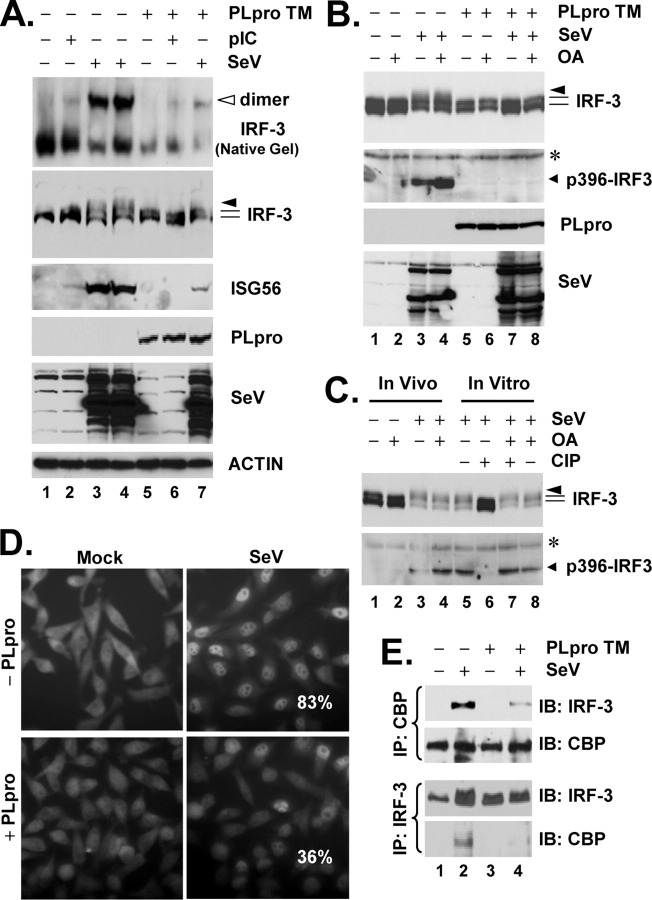

SARS-CoV PLpro inhibits virus-induced IRF-3 phosphorylation, dimerization, and nuclear translocation.A, HeLa PLpro-4 cells were manipulated to repress or induce PLpro-TM expression for 3 days and were subsequently mock-treated or incubated with 50 μg/ml poly(I-C) in culture medium for 6 h or challenged with SeV for 16 h. Cell lysates were separated on native PAGE followed by immunoblot analysis to detect IRF-3 monomer and dimer forms (top panel, empty arrowhead indicates IRF-3 dimer), or subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis of IRF-3, ISG56, PLpro, SeV, and actin (lower panels). B, HeLa PLpro-4 cells were cultured to repress or induce PLpro-TM expression and subsequently mock-infected or infected with SeV for 16 h. Where indicated, cells were incubated with 0.05 μg/ml of OA for the last 4 h of SeV infection/mock infection. Cells were then harvested for immunoblot analysis of IRF-3, p396-IRF3, PLpro (anti-V5), and SeV. Asterisk denotes a nonspecific band. C, lanes 1-4, HeLa cells were mock-infected or infected with SeV for 16 h. Where indicated, OA was included in the last 4-h duration of infection/mock infection. Lanes 5-8, cell lysates of HeLa cells infected with SeV were mock-treated, treated with CIP, OA, or CIP in the presence of OA, as indicated under “Experimental Procedures.” IRF-3 and p396-IRF3 were detected by immunoblot analysis. Asterisk denotes a nonspecific band. D, immunofluorescence staining of IRF-3 subcellular localization in HeLa PLpro-4 cells repressed (upper panels) or induced (lower panels) for PLpro-TM expression and mock-infected (left) or infected (right) with SenV for 16 h. Numbers in SeV-infected cells were the averages of the percentage of cells that had IRF-3 nuclear translocation and were counted from 10 random fields (×40 magnification). E, HeLa PLpro-4 cells were cultured to repress or induce PLpro-TM expression and subsequently mock-infected or infected with SeV. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with a rabbit anti-CBP antibody (upper panels) or with a rabbit anti-IRF-3 antiserum (lower panels). The immunoprecipitates were separated on SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblot (IB) analysis of IRF-3 (using an mAb anti-IRF-3) or CBP (using a rabbit anti-CBP antibody).

SARS-CoV PLpro Interacts with IRF-3 and Inhibits Virus-induced IRF-3 Phosphorylation, Dimerization, and Nuclear Translocation—To determine how SARS-CoV PLpro inhibits IRF-3 activation, we conducted immunoblot analysis of the activation status of IRF-3 in PLpro-inducible cells, repressed or induced for PLpro-TM expression and mock-treated or treated with poly(I-C) or infected with SeV. We found that de-repression of PLpro-TM significantly down-regulated the phosphorylation (IRF-3 panel) and dimerization (native gel panel) of IRF-3 (Fig. 5A). PLpro-TM induction also ablated SeV-induced phosphorylation of IRF-3 at Ser396 (Fig. 5B, compare lane 7 versus 3), a minimal phospho-acceptor site required for in vivo activation of IRF-3 in response to virus and dsRNA (71). This could not be attributed to de-phosphorylation of IRF-3, as treatment of PLpro-expressing cells with a potent PP2A phosphatase inhibitor, okadaic acid (72), failed to restore SeV-induced IRF-3 phosphorylation (Fig. 5B, compare lane 8 versus 7 and 4). As positive controls, treatment of SeV-infected HeLa cell lysates with CIP effectively de-phosphorylated IRF-3 (Fig. 5C, compare lane 5 versus 6). The action of CIP, however, was completely blocked by OA (Fig. 5C, compare lane 7 versus 6). Consistent with the inhibition on IRF-3 phosphorylation and dimerization, SeV induced IRF-3 nuclear translocation (Fig. 5D), and its association with the transcriptional co-activator CBP (Fig. 5E, compare lane 4 versus 2) was greatly reduced in PLpro-expressing cells.

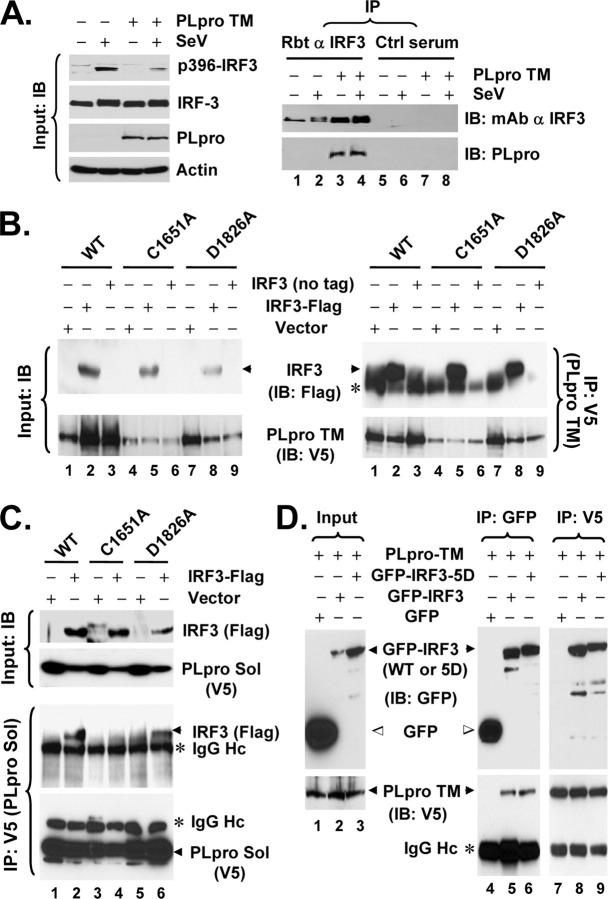

Interestingly, in co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiments, we reproducibly observed that PLpro-TM interacted with IRF-3 (Fig. 6A , right panels). The association of PLpro with IRF-3 was specific, as it was detected only when IRF-3 antiserum, but not a control serum, was used for the co-IP experiments (Fig. 6A , right panels, compare lanes 3 and 4 versus 7 and 8). Furthermore, co-IP experiments did not reveal an interaction of PLpro with RIG-I, MAVS, TBK1, or IKKε (data not shown). To determine whether the inhibition of IRF-3 activation by PLpro is related to its interaction with IRF-3, we conducted co-IP experiments determining the ability of different PLpro mutants to interact with IRF-3. We found that WT and the protease-deficient mutant forms (C1651A and D1826A) of PLpro-TM all interacted with IRF-3 (Fig. 6B), consistent with their ability to inhibit IRF-3 activation (Fig. 2). In the case of PLpro-Sol, although D1826A substitution had no effect on its association with IRF-3, the C1651A Sol mutant lost its ability to interact with IRF-3 (Fig. 6C). This is in agreement with the fact that D1826A PLpro Sol acts similarly as the WT protein to inhibit IFN induction (Fig. 2E), whereas C1651A PLpro Sol is no longer able to do so (Fig. 2D). We speculate that addition of the downstream TM domains to PLpro Sol may render the conformation/folding of PLpro less liable to the C1651A substitution, thereby allowing C1651A PLpro-TM to retain its ability to interact with IRF-3. Next, we investigated whether PLpro can also interact with IRF-3 5D, a constitutively active mutant that mimics the C-terminal phosphorylated IRF-3. This was an intriguing question, as PLpro did not inhibit the activation of IFN response by IRF-3 5D (Fig. 3). We found that both WT and 5D versions of GFP-tagged IRF-3 interacted with PLpro-TM, whereas the GFP control did not (Fig. 6D). We conclude from these experiments that SARS-CoV PLpro physically interacts in a complex with IRF-3, leading to inhibition of IRF-3 phosphorylation and its subsequent dimerization, nuclear translocation, and activation of the expression of IRF-3 target genes. However, we note that PLpro does not seem to inhibit the downstream IFN induction once IRF-3 is phosphorylated and activated.

FIGURE 6.

SARS-CoV PLpro interacts with IRF-3.A, HeLa PLpro-4 cells were cultured to repress or induce PLpro-TM expression and subsequently mock-infected or infected with SeV for 16 h. Left panels, expression of p396-IRF-3, total IRF-3, PLpro, and actin proteins in cell lysates were determined by immunoblot (IB) analysis. Right panels, cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with a rabbit anti-IRF-3 antibody (lanes 1-4) or a control rabbit serum (lanes 5-8). The immunoprecipitates were separated on SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblot analysis of IRF-3 (using an mAb anti-IRF-3) and PLpro (using an mAb anti-V5 tag). B, HEK293 cells were transfected with WT (lanes 1-3), C1651A (lanes 4-6), or D1826A (lanes 7-9) PLpro-TM, respectively, and, where indicated, with an empty vector (lanes 1, 4, and 7), or a vector expressing FLAG-IRF-3 (lanes 2, 5, and 8) or untagged IRF-3 (lanes 3, 6, and 9). Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-V5 (PLpro-TM), followed by immunodetection of FLAG-IRF-3 (anti-FLAG) or PLpro-TM (anti-V5) (right panels). Asterisk denotes IgG heavy chain. Immunoblot analysis of input for FLAG-IRF-3 and PLpro-TM is shown in left panels. All three forms of PLpro-TM interacted with IRF-3. C, HEK293 cells were transfected with WT (lanes 1 and 2), C1651A (lanes 3 and 4), or D1826A (lanes 5 and 6) PLpro-Sol, respectively, and, where indicated, with an empty vector (lanes 1, 3, and 5) or a vector expressing FLAG-IRF-3 (lanes 2, 4, and 6). Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-V5 (PLpro-Sol), followed by immunodetection of FLAG-IRF-3 (anti-FLAG) or PLpro-Sol (anti-V5) (lower panels). Immunoblot analysis of input for FLAG-IRF-3 and PLpro-Sol is shown in upper panels. Note that WT and D1826A PLpro-Sol interacted with IRF-3, whereas C1651A PLpro-Sol did not. D, HeLa PLpro-4 cells induced for PLpro-TM expression were transfected with GFP, GFP-IRF-3, or GFP-IRF3-5D, respectively. Cell lysates were subjected to co-IP experiments using either GFP antibody or V5 antibody for immunoprecipitation, followed by immunoblot analysis of the immunoprecipitates using anti-GFP or anti-V5 antibodies. Note that both GFP-IRF3 and GFP-IRF3-5D were associated with PLpro-TM (detected by anti-V5), whereas free GFP was not.

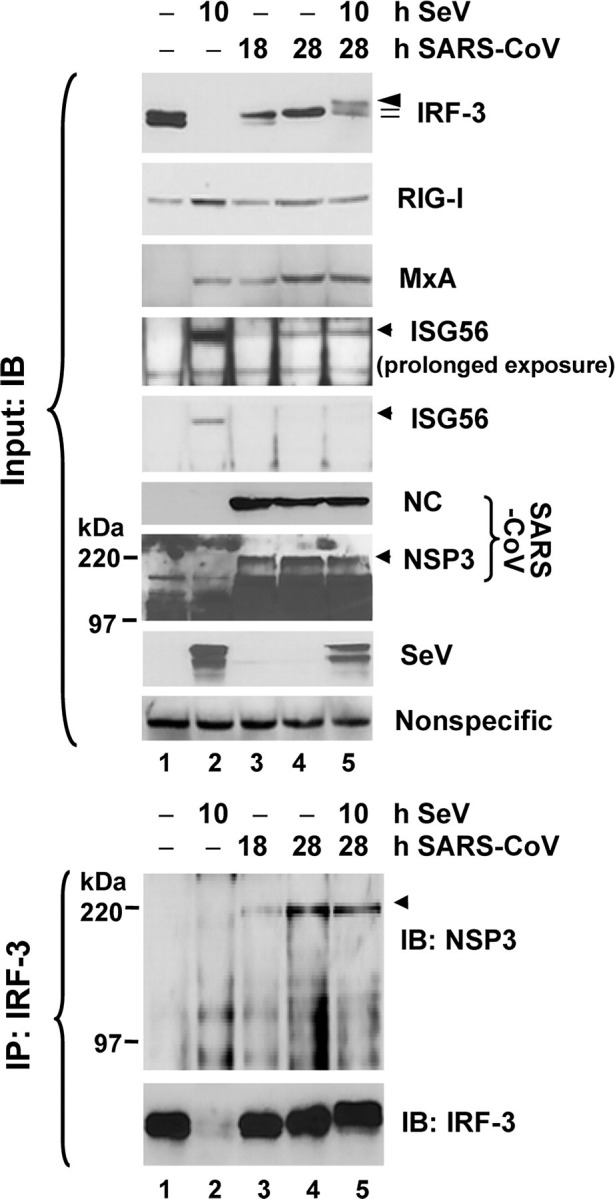

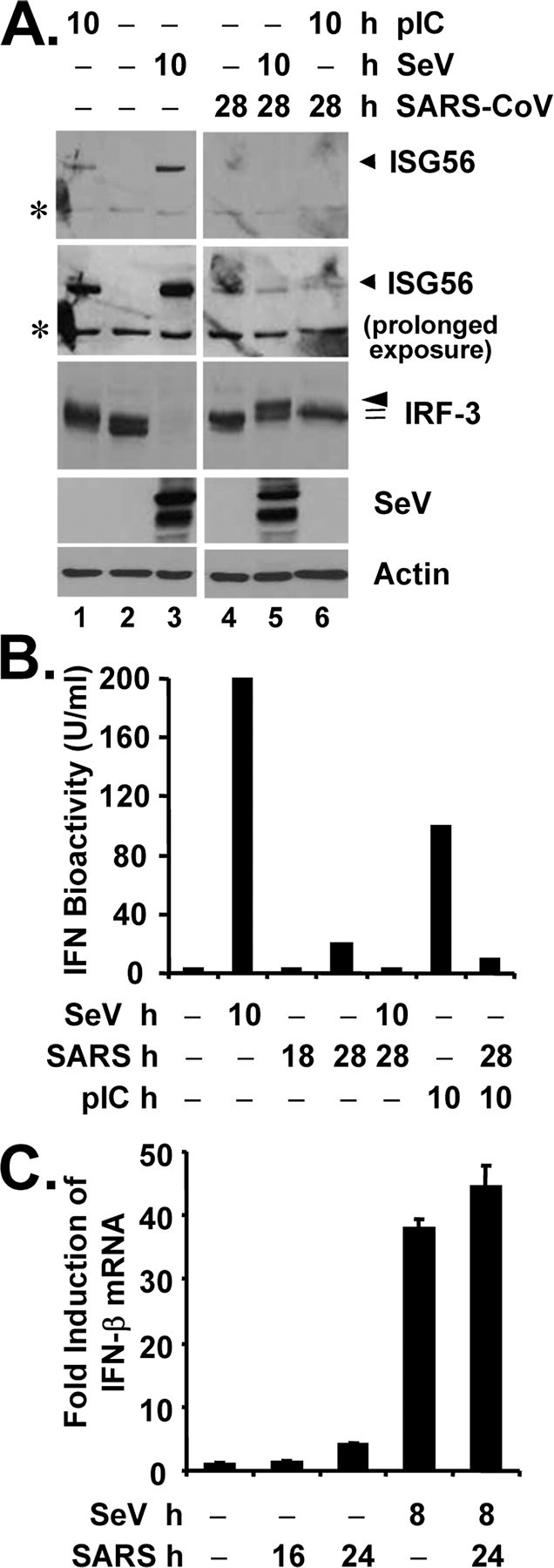

Association of nsp3 with IRF-3 and Regulation of IFN Responses in Cells Infected with SARS-CoV—Next, we investigated whether the IRF-3 pathway is regulated in SARS-CoV-infected cells, and whether nsp3, which embraces the PLpro domain, interacts with IRF-3 in the context of SARS-CoV replication. In MA104 cells, SeV infection induced the degradation of IRF-3 and significantly up-regulated the expression of ISG56, MxA, and RIG-I proteins early after infection (10 h postinfection) (Fig. 7 , upper panels, compare lanes 2 versus 1). Again, as described in Fig. 1, infection of SARS-CoV triggered a weak ISG response late after infection (at 28 h) without inducing the phosphorylation and degradation of IRF-3 (Fig. 7, upper panels, compare lanes 4 and 3 versus 1). Importantly, pre-infection of SARS-CoV for 18 h ablated the further up-regulation of multiple ISG proteins, ISG56, MxA, and RIG-I by SeV superinfection (Fig. 7, upper panels, compare lanes 5 versus 2 and 4). Although SARS-CoV infection did not ablate the phosphorylation of IRF-3 induced by SeV challenge, it caused a marked, reproducible reduction in IRF-3 degradation following SeV superinfection (Fig. 7, IRF-3 panel, compare lanes 5 versus 2, and Fig. 8A , IRF-3 panel, compare lanes 5 versus 3). Similar abrogation of the up-regulation of ISG proteins by SARS-CoV was observed when poly(I-C) transfection was used in lieu of SeV to trigger the responses (Fig. 8A, compare lanes 6 versus 1 and 4). Consistent with the immunoblot analysis data, whereas SeV infection or poly(I-C) transfection induced considerable amounts of IFN that were released to the culture supernatant, as measured by IFN bioactivity assay, there was little or no detectable IFN antiviral activity in SeV-challenged or poly(I-C)-treated MA104 cells that were pre-infected with SARS-CoV (Fig. 8B).

FIGURE 7.

SARS-CoV nsp3 is associated with IRF-3 in cells infected with SARS-CoV. MA104 cells were mock-infected (lane 1), infected with SeV for 10 h (lane 2), infected with SARS-CoV (m.o.i. = 10) for 18 and 28 h (lanes 3 and 4), respectively, or infected with SARS-CoV for 18 h and then superinfected with SeV for an additional 10 h (lane 5). Expression of IRF-3, RIG-I, MxA, ISG56, SARS-CoV NC, and nsp3, and SeV proteins in cell lysates was determined by immunoblot (IB) analysis (upper panels). A nonspecific band detected by the rabbit anti-MxA antiserum (bottom panel) indicates equal loading. Data shown are representative of three independently conducted experiments. In lower panels, the cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with a rabbit anti-IRF3 antiserum, followed by immunoblot analysis of SARS-CoV nsp3, and IRF-3 (using an mAb anti-IRF3 antibody). Data shown are representative of two independently conducted experiments.

FIGURE 8.

Regulation of IFN responses in cells infected with SARS-CoV.A, MA104 cells were mock-infected (lanes 1-3) or infected with SARS-CoV (m.o.i. = 10) for 18 h (lanes 4-6), followed by mock treatment (lanes 2 and 4), transfection of poly(I-C) (lanes 1 and 6), or superinfection of SeV (lanes 3 and 5) for 10 h, respectively (a total of 28 h after mock or SARS-CoV infection under these conditions). Immunoblot analysis of cell lysates for expression of ISG56, IRF-3, SeV, and actin is shown. Asterisks in ISG56 panels denote a nonspecific band. B, MA104 cells were mock-infected, infected with SeV for 10 h, infected with SARS-CoV (m.o.i. = 10) for 18 or 28 h, or transfected with poly(I-C) for 10 h, respectively, or pre-infected with SARS-CoV for 18 h and then superinfected with SeV or transfected with poly(I-C) for additional 10 h (a total of 28 h after SARS-CoV infection under these conditions). Cell-free culture supernatants were collected, irradiated, and subjected to IFN bioactivity assay against vesicular stomatitis virus as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Bars indicate IFN bioactivity (units/ml) in culture supernatants under the indicated conditions. C, MA104 cells were mock-infected, infected with SeV for 8 h, infected with SARS-CoV (m.o.i. = 10) for 16 or 24 h, or pre-infected with SARS-CoV for 16 h and then superinfected with SeV for additional 8 h. Cells were harvested for total RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and subsequent real time RT-PCR detection of IFN-β mRNA. Data shown are representative of two independently conducted experiments.

Remarkably, we were able to demonstrate a reproducible association of nsp3 with IRF-3 in SARS-CoV-infected MA104 cells by co-IP, and the interaction seemed to be strengthened with time after infection (Fig. 7, lower panels, lanes 3 and 4). SeV superinfection did not have a demonstrable effect on the association between nsp3 and IRF-3 (lane 5). Surprisingly and not currently understood, although SARS-CoV infection ablated the induction of IFN and multiple ISG proteins by SeV superinfection or dsRNA transfection (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8, A and B), this did not correlate with an inhibition on up-regulation of IFN-β mRNA transcript (Fig. 8C). Although the role of SARS-CoV nsp3 in regulation of IRF-3-dependent innate immunity remains to be further investigated, these data suggest that SARS-CoV has developed additional strategies to inactivate innate cellular defenses by disrupting the expression of a subset of cellular antiviral proteins from their mRNAs.

The IRF-3 Pathway Contributes to Control of SARS-CoV Replication in Cultured Cells—While this study was in process, three other SARS-CoV proteins, ORF3b, ORF6, and N, were reported to function as IFN antagonists by inhibiting IRF-3 activation (35). The fact that multiple SARS-CoV proteins have evolved the ability to disrupt IRF-3 function prompted us to hypothesize that IRF-3-dependent innate defenses may contribute significantly to cellular control of SARS-CoV infection. We thus sought to determine whether IRF-3 signaling regulates cellular permissiveness for SARS-CoV replication. To answer this question, we developed Huh7 cells (designated Huh7/DN-18) that conditionally express a dominant negative form of IRF-3 (DN-IRF-3) (17) under the control of the Tet-Off promoter. Huh7 cells were reported to be susceptible for SARS-CoV infection, and we have confirmed this independently in our laboratories.4 As seen in Fig. 9A, expression of DN-IRF-3 in Huh7/DN-18 cells was tightly regulated by tet and only detectable when tet was withdrawn from the culture medium (IRF-3 panel, compare lanes 3 and 4 versus 1 and 2). Confirming its function, DN-IRF-3 induction significantly diminished SeV-induced expression of ISG56 (Fig. 9A , ISG56 panel, compare lanes 4 versus 2). We then manipulated DN-18 cells to repress and induce DN-IRF-3 expression, respectively, and challenged them with a low dose of SARS-CoV (m.o.i. = 0.01). The yields of infectious progeny SARS-CoV in culture supernatants were determined dynamically during the 3-day follow-up period. In three independently conducted experiments, we reproducibly observed that SARS-CoV replicated at a significantly faster rate in cells induced for DN-IRF-3 expression than in those under continuous repression, releasing up to 2-log higher titers of infectious progeny viruses (Fig. 9B). Consistent with this, CPE was observed in as many as 70% of infected cells induced for DN-IRF-3 expression, whereas in only 30% of cells without DN-IRF-3 expression at day 3 postinfection (data not shown). Taken together, these data suggest that IRF-3 signaling contributes to the cellular control of SARS-CoV infection.

DISCUSSION

Data regarding the interactions of SARS-CoV with the innate immune system of host cells have been controversial. Although it is conceivable that professional IFN-producing, plasmacytoid DCs may sense single-stranded RNAs derived from SARS-CoV in endosome compartments by TLR7 and initiate an IFN response, as recently demonstrated by Cervantes-Barragan et al. (73), it is currently not known whether parenchymal cells, including those from the lung epithelium, which represent the major target for SARS-CoV infection in vivo, can sense components or products of the invading SARS-CoV and initiate an innate defense response. Furthermore, it has been controversial whether SARS-CoV evades host innate immunity by simply avoiding detection by the host or has acquired mechanisms to actively block host antiviral responses (35, 37, 38).

Using a highly relevant human lung/bronchial epithelial cell line (Calu-3) for SARS-CoV infection (47) and a fetal green monkey kidney-derived fibroblast cell line (MA104) competent for IFN production, we have demonstrated in this study that SARS-CoV is sensed by the innate immune system in parenchymal cells that actively support the replication of SARS-CoV. This conclusion is supported by the fact that infection of SARS-CoV triggers a weak, yet reproducible induction of IFN-β mRNA as well as a low level expression of a subset of ISGs in both cell types (Figs. 1, 7, and 8). Among these ISGs, induction of MxA and RIG-I is known to depend on functional JAK-STAT signaling downstream of type I IFN receptors (58, 74). Moreover, disruption of IRF-3 function by conditional expression of a dominant negative IRF-3 mutant significantly up-regulated SARS-CoV replication in cell culture (Fig. 9), indicating that IRF-3 dependent innate defenses are likely being triggered by SARS-CoV and have a restrictive effect on viral replication. In agreement with a previously published study in HEK293 cells (21), infection of SARS-CoV did not trigger demonstrable phosphorylation of IRF-3 in both Calu-3 and MA104 cells, despite the latter being readily induced by SeV (Fig. 1 and Fig. 7) or poly(I-C) transfection (Fig. 8A and data not shown). Nonetheless, we were able to reproducibly observe a shift in the two IRF-3 basal forms from the lower to the higher mass in MA104 cells late postinfection (Fig. 1B and Fig. 7), which represents a low level of IRF-3 activation pattern similar to that previously reported in HSV-1-infected A549 cells (59). The reasons Calu-3 cells do not show such a shift in the two IRF-3 forms are currently not known. Although cell type-specific differences could be involved, this seems less likely as both cell types respond to SeV well by rapidly inducing the phosphorylation and degradation of IRF-3 (Fig. 1). It is reasonable to speculate that this difference could be related to an earlier, more robust replication of SARS-CoV in MA104 cells (Fig. 1 and data not shown), as the degree of IRF-3 phosphorylation has been shown to correlate with the level of viral replication (59).

Although we have shown that SARS-CoV infection is sensed by and triggers innate immune responses of host cells, the IFN response induced by SARS-CoV shows delayed kinetics, and the overall magnitude is much lower than that triggered by SeV or the transfected dsRNA analog, poly(I-C) (Fig. 1). Replication of SARS-CoV occurs within double membrane vesicles derived from endoplasmic reticulum membranes (75, 76, 77, 78), which may prevent the recognition of viral PAMPs generated during SARS-CoV replication by host PRRs (37, 38). Although this evasion mechanism may contribute to the absence of IRF-3 phosphorylation early after infection, it does not explain the blockade of induction of IFN antiviral activity and the up-regulation of multiple ISG proteins that we have observed in SARS-CoV infected cells that were superinfected with SeV or transfected with poly(I-C) (Fig. 8B, Fig. 7, and Fig. 8A). Instead, our data suggest that SARS-CoV has evolved strategies to actively block host innate defenses. Consistent with this notion, multiple SARS-CoV proteins have recently been suggested to antagonize various aspects of the host innate immunity, as those reported with ORF3b, ORF6, N, and nsp1 (35, 36). We have shown in this study that the PLpro domain of nsp3 also serves as an IFN antagonist. However, it is important to consider the possibility that both “stealth” and “counteraction” mechanisms may be involved in virus-host interactions in SARS-CoV-infected cells and regulated in a coordinated manner at different stages of viral life cycle, in order to circumvent host responses and offer SARS-CoV a maximal survival advantage.

In searching for an IFN antagonist encoded by SARS-CoV, we identified the PLpro domain of nsp3 as a specific, potent inhibitor for IRF-3 activation. As one of two major SARS-CoV proteases, PLpro comprises part of the nsp3 protein and is responsible for processing the polyprotein junctions spanning nsp1 to nsp4. Intriguingly, PLpro was recently shown to have unexpected DUB/delSGylation activities (29, 30), which prompted us to explore its effect on innate immune signaling. We found that PLpro disrupts IFN induction by acting downstream of the IRF-3 kinases, TBK1 and IKKε, and inhibits the induction of IRF-3-dependent genes via both TLR3 and RIG-I/MDA5 pathways (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5). Importantly, we demonstrated this upon the transient constitutive expression of PLpro or its stable, conditional expression in a tet-regulated manner. Furthermore, we show the inhibitory effect was dose-dependent on the expression of PLpro (Fig. 2, B and C, and Fig. 4B). Unlike NS3/4A of HCV and GBV-B or 3ABC of hepatitis A virus (39, 46, 63), SARS-CoV PLpro does not rely on its protease activity to disrupt IFN responses (Fig. 2). Instead, it involves an interaction between PLpro and IRF-3 (Fig. 6) and inhibits the phosphorylation, dimerization, and nuclear translocation of IRF-3 (Fig. 5), prerequisites for its activation as a transcription factor to turn on the type I IFN response (17). The involvement of PLpro-IRF-3 interaction in the IFN antagonist function of PLpro is supported by the fact that the ability to interact with IRF-3 by various PLpro mutants (Fig. 6, B and C) seems to correlate with their capability of inhibiting IFN response (Fig. 2). Specifically, the C1651A PLpro-Sol mutant that loses its inhibitory effect on IFN response (Fig. 2D) is also unable to interact with IRF-3 (Fig. 6C). However, precisely how this interaction contributes to the function of PLpro is not known. We speculate that the association of PLpro with IRF-3 may affect the recognition of IRF-3 by the IRF-3 kinases and/or otherwise prevent its interactions with the IRF-3 kinases and/or other cellular interaction partners essential for IRF-3 activation. Moreover, our data suggest that PLpro has to act at a step before the phosphorylation of IRF-3, as PLpro does not inhibit the activation of IFN response by the phospho-mimetic IRF-3 5D (Fig. 3, B and C), despite of its capability of interacting with IRF-3 5D (Fig. 6D).

At present, we do not know whether the DUB/delSGylation activity contributes to the function of PLpro in disrupting IRF-3 activation. Although we have shown that its protease activity is dispensable, thus far we have not been able to identify specific mutation(s) in PLpro that allow us to dissect the protease activity of PLpro from its DUB activity. The D1826A protease-inactive mutant PLpro loses ∼99% of the DUB activity in vitro (29), yet it still acts as good as the WT protein to inhibit the IFN response (Fig. 2, C and E). Although this would argue against the involvement of the DUB activity of PLpro in mediating the IRF-3 blockade, it does not exclude the possibility that only 1% of the DUB activity is needed to fully execute the inhibitory function of PLpro on IRF-3 activation. Intriguingly, it has been reported that several cellular DUB/delSGylation enzymes inhibit innate immune signaling independent of their DUB/delSGylation function. For instance, the ubiquitin editing enzyme A20 acts through its C-terminal zinc finger domain of the ubiquitin ligase to inhibit IRF-3-dependent gene expression, as deletion of the N-terminal DUB domain has no significant effect on the inhibitory effect of A20 (62). Similarly, the ubiquitin-specific protease Ubp43 negatively regulates IFN signaling through its interaction with the IFNAR2 subunit and independent of its isopeptidase activity toward ISG15 (79).

Ubiquitination is known to play an important role in NF-κB signaling (60). However, we did not find a specific inhibitory effect of PLpro on the induction of endogenous NF-κB-dependent genes, A20 (70) and IL-6 (80), following SeV challenge or pIC treatment (Fig. 4C), although we did observe some inhibition of activation of the NF-κB-dependent PRDII promoter in cells with transient, ectopic expression of PLpro (data not shown). Future reverse genetics approaches engineering viable SARS-CoV mutants, which carry substitutions in PLpro that disrupt its DUB/delSGylation activities while retaining the protease activity (assuming that this is possible), would help to address the specific biological roles of the DUBdeISGylation activities of PLpro in virus-host interactions and pathogenesis of SARS-CoV infection.

For reasons that remain poorly understood, we did not observe a blockade of SARS-CoV replication on phosphorylation of IRF-3 by SeV or transfected poly(I-C) in MA104 cells, although we demonstrate that SeV-induced degradation of IRF-3 was dramatically reduced (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8A). We were also unable to demonstrate an inhibition on SeV induction of IFN-β mRNA transcript by prior SARS-CoV infection (Fig. 8C). This is consistent with two recent reports that mouse hepatitis virus and SARS-CoV do not block poly(I-C) or SeV-induced IRF-3 nuclear translocation (37, 38), but it is contradictory to the fact that multiple SARS-CoV proteins, including PLpro, ORF3b, ORF6, and N (35), can efficiently inhibit IRF-3 activation. The treatments used to trigger IFN response (SeV or poly(I-C) transfection) were administered at 18 h postinfection of SARS-CoV (m.o.i. = 10) when SARS-CoV growth kinetics had reached its plateau, and about 50% cells were infected as determined by immunofluorescence staining for SARS-CoV nsp3 antigen (data not shown). In contrast, in the study conducted by Versteeg et al. (38), poly(I-C) was transfected at 1 h postinfection of SARS-CoV, and SeV was coinfected with SARS-CoV. It is possible that uninfected cells still responded to SeV or poly(I-C), which may have diluted the inhibitory effect of PLpro and/or other viral IFN antagonists. However, it is necessary to determine whether PLpro can inhibit IRF-3 activation when expressed in the context of the entire nsp3 protein. However, thus far we have not been able to clone the full-length nsp3 cDNA in a mammalian expression vector. The reasons for this remain unclear but could be due to a toxic effect of nsp3 in E. coli. One may also speculate that PLpro, as an essential viral protease involved in viral replication, is sequestered within the replication complex in SARS-CoV-infected cells, preventing its binding to IRF-3. Although less likely, it is also possible that SeV replication or poly(I-C) transfection may disrupt the double membrane vesicle, resulting in the release of additional SARS-CoV PAMPs that trigger IFN responses via as yet unknown mechanisms that are not sensitive to the inhibition of PLpro. Nevertheless, we were able to reproducibly observe that nsp3 co-precipitates with IRF-3 in SARS-infected cells (Fig. 7, lower panels), although further studies are needed to determine whether such an interaction is direct or through another protein partner(s). Furthermore, the PLP2 of NL63, another closely related coronavirus, also interacts with IRF-3 and has a similar inhibitory effect on IFN responses.5 Therefore, it seems that inhibition of IRF-3 activation by PLpro is a shared feature of at least some other coronaviruses. Future reverse genetics approaches engineering viable SARS-CoV mutants, which carry substitutions in PLpro that disrupt its interaction with IRF-3 while retaining the protease activity, would help us to fully understand the contribution of PLpro-IRF-3 interaction in the regulation of host innate immunity in SARS-CoV-infected cells.

Our data demonstrated that SARS-CoV infection ablates the up-regulation of protein levels of several ISGs, e.g. ISG56, RIG-I, etc., and the secretion of detectable IFN antiviral activity (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8, A and B). This indicates that SARS-CoV has developed additional strategies to inactivate innate cellular defenses by disrupting the expression of at least a subset of cellular antiviral proteins from their mRNAs. Whether this reflects a selective disruption of certain cellular mRNA translation, nuclear export, or turnover or is because of a nonspecific degradation of mRNAs that was recently reported with nsp1 (36) requires further investigation.

Our data suggest that IRF-3-dependent host defenses contribute to cellular control of SARS-CoV infection, as disruption of IRF-3 function significantly enhanced the replication of SARS-CoV (Fig. 9). This is consistent with the finding that SARS-CoV triggers a weak IFN response in cell culture (Fig. 1) and that multiple SARS-CoV proteins, including PLpro identified in this study, as well as several others, ORF3b, ORF6, and N (35), have the ability to inhibit IRF-3 activation. Although the biological relevance of this newly discovered function for these SARS-CoV proteins remains to be carefully determined in the context of SARS-CoV infection, it suggests that limiting IRF-3-dependent innate immunity is important for establishment of SARS-CoV infection. Further studies are needed, however, regarding the nature of the cellular effectors downstream of IRF-3 that negatively regulate SARS-CoV replication. Specifically, whether this involves cellular genes of direct IRF-3 target or requires a soluble factor to be secreted by infected cells (e.g. IFN). Moreover, it remains to be elucidated regarding the innate signaling pathways that are triggered by SARS-CoV and lead to the IRF-3-dependent innate defenses against SARS-CoV infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stanley Lemon for support and critical review of the manuscript; Samuel Baron for advice with the IFN bioassay; Kate Fitzgerald, Takashi Fujita, John Hiscott, Zhijian Chen, Ilkka Julkunen, Michael David, Ganes Sen, Michael Gale, Nancy Raab-Traub, Christina Ehrhardt, Thomas Ksiazek, and Mohammad Jamaluddin for sharing reagents. We are grateful to Mardelle Susman for careful reading of the manuscript; the University of Texas Medical Branch Optimal Imaging Core for assistance with confocal microscopy, and the University of Texas Medical Branch Sealy Center for Cancer Biology Real Time PCR core for assistance with real time RT-PCR assays.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: IFN, interferon; SARS-CoV, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus; PLpro, papain-like protease; PAMP, pathogen-associated molecular pattern; IRF-3, interferon regulatory factor-3; ISG, interferon-stimulated gene; dsRNA, double-stranded RNA; TLR, Toll-like receptor; TRIF, Toll-IL1 receptor domain-containing adaptor inducing IFN-β; RIG-I, retinoic acid-inducible gene I; MDA5, melanoma differentiation associated gene-5; MAVS, mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein; TBK1, Tank-binding kinase 1; DUB, deubiquitination; SeV, Sendai virus; CPE, cytopathic effect; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; DN, dominant negative; mAb, monoclonal antibody; pAb, polyclonal antibody; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; IL, interleukin; CIP, calf intestine alkaline phosphatase; HAU, hemagglutinin unit; RT, reverse transcription; q-RT, quantitative RT; WT, wild type; GFP, green fluorescent protein; tet, tetracycline; PRR, pattern recognition receptors; m.o.i., multiplicity of infection; OA, okadaic acid; co-IP, co-immunoprecipitation; nsp, nonstructural protein.

C. T. K. Tseng and K. Li, unpublished observations.

K. Li and C. T. K. Tseng, unpublished observations.

Z. B. Chen and S. C. Baker, unpublished data.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Sen G.C. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2001;55:255–281. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goutagny N., Kim M., Fitzgerald K.A. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:555–557. doi: 10.1038/ni0606-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stetson D.B., Kim R. Immunity. 2006;25:373–381. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia-Sastre A., Kim C.A. Science. 2006;312:879–882. doi: 10.1126/science.1125676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawai T., Kim S. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:131–137. doi: 10.1038/ni1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoneyama M., Kim M., Natsukawa T., Shinobu N., Imaizumi T., Miyagishi M., Taira K., Akira S., Fujita T. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:730–737. doi: 10.1038/ni1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seth R.B., Kim L., Chen Z.J. Cell Res. 2006;16:141–147. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meylan E., Kim J. Mol. Cell. 2006;22:561–569. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sen G.C., Kim S.N. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexopoulou L., Kim A.C., Medzhitov R., Flavell R.A. Nature. 2001;413:732–738. doi: 10.1038/35099560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kato H., Kim O., Sato S., Yoneyama M., Yamamoto M., Matsui K., Uematsu S., Jung A., Kawai T., Ishii K.J., Yamaguchi O., Otsu K., Tsujimura T., Koh C.S., Reis e Sousa C., Matsuura Y., Fujita T., Akira S. Nature. 2006;441:101–105. doi: 10.1038/nature04734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hornung V., Kim J., Kim S., Brzozka K., Jung A., Kato H., Poeck H., Akira S., Conzelmann K.K., Schlee M., Endres S., Hartmann G. Science. 2006;314:994–997. doi: 10.1126/science.1132505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pichlmair A., Kim O., Tan C.P., Naslund T.I., Liljestrom P., Weber F., Reis e Sousa C. Science. 2006;314:997–1001. doi: 10.1126/science.1132998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma S., Kim B.R., Grandvaux N., Zhou G.P., Lin R., Hiscott J. Science. 2003;300:1148–1151. doi: 10.1126/science.1081315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fitzgerald K.A., Kim S.M., Faia K.L., Rowe D.C., Latz E., Golenbock D.T., Coyle A.J., Liao S.M., Maniatis T. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:491–496. doi: 10.1038/ni921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoneyama M., Kim W., Fujita T. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2002;22:73–76. doi: 10.1089/107999002753452674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin R., Kim C., Pitha P.M., Hiscott J. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:2986–2996. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diebold S.S., Kim T., Hemmi H., Akira S., Reis e Sousa C. Science. 2004;303:1529–1531. doi: 10.1126/science.1093616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heil F., Kim H., Hochrein H., Ampenberger F., Kirschning C., Akira S., Lipford G., Wagner H., Bauer S. Science. 2004;303:1526–1529. doi: 10.1126/science.1093620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peiris J.S., Kim Y., Yuen K.Y. Nat. Med. 2004;10:S88–S97. doi: 10.1038/nm1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spiegel M., Kim A., Martinez-Sobrido L., Cros J., Garcia-Sastre A., Haller O., Weber F. J. Virol. 2005;79:2079–2086. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.4.2079-2086.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yount B., Kim R.S., Sims A.C., Deming D., Frieman M.B., Sparks J., Denison M.R., Davis N., Baric R.S. J. Virol. 2005;79:14909–14922. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14909-14922.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ziebuhr J. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2006;581:3–11. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-33012-9_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ziebuhr J. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2005;287:57–94. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26765-4_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marra M.A., Kim S.J., Astell C.R., Holt R.A., Brooks-Wilson A., Butterfield Y.S., Khattra J., Asano J.K., Barber S.A., Chan S.Y., Cloutier A., Coughlin S.M., Freeman D., Girn N., Griffith O.L., Leach S.R., Mayo M., McDonald H., Montgomery S.B., Pandoh P.K., Petrescu A.S., Robertson A.G., Schein J.E., Siddiqui A., Smailus D.E., Stott J.M., Yang G.S., Plummer F., Andonov A., Artsob H., Bastien N., Bernard K., Booth T.F., Bowness D., Drebot M., Fernando L., Flick R., Garbutt M., Gray M., Grolla A., Jones S., Feldmann H., Meyers A., Kabani A., Li Y., Normand S., Stroher U., Tipples G.A., Tyler S., Vogrig R., Ward D., Watson B., Brunham R.C., Krajden M., Petric M., Skowronski D.M., Upton C., Roper R.L. Science. 2003;300:1399–1404. doi: 10.1126/science.1085953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rota P.A., Kim M.S., Monroe S.S., Nix W.A., Campagnoli R., Icenogle J.P., Penaranda S., Bankamp B., Maher K., Chen M.H., Tong S., Tamin A., Lowe L., Frace M., DeRisi J.L., Chen Q., Wang D., Erdman D.D., Peret T.C., Burns C., Ksiazek T.G., Rollin P.E., Sanchez A., Liffick S., Holloway B., Limor J., McCaustland K., Olsen-Rasmussen M., Fouchier R., Gunther S., Osterhaus A.D., Drosten C., Pallansch M.A., Anderson L.J., Bellini W.J. Science. 2003;300:1394–1399. doi: 10.1126/science.1085952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harcourt B.H., Kim D., Kanjanahaluethai A., Bechill J., Severson K.M., Smith C.M., Rota P.A., Baker S.C. J. Virol. 2004;78:13600–13612. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.24.13600-13612.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ratia K., Kim K.S., Santarsiero B.D., Barretto N., Baker S.C., Stevens R.C., Mesecar A.D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:5717–5722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510851103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barretto N., Kim D., Ratia K., Chen Z., Mesecar A.D., Baker S.C. J. Virol. 2005;79:15189–15198. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.24.15189-15198.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindner H.A., Kim N., Lytvyn V., Lachance P., Sulea T., Menard R. J. Virol. 2005;79:15199–15208. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.24.15199-15208.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng L., Kim U., Reymond J.L. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Solorzano A., Kim R.J., Lager K.M., Janke B.H., Garcia-Sastre A., Richt J.A. J. Virol. 2005;79:7535–7543. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7535-7543.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quinlivan M., Kim D., Garcia-Sastre A., Cullinane A., Chambers T., Palese P. J. Virol. 2005;79:8431–8439. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.8431-8439.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Z., Kim Y., Jiao P., Wang A., Zhao F., Tian G., Wang X., Yu K., Bu Z., Chen H. J. Virol. 2006;80:11115–11123. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00993-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kopecky-Bromberg S.A., Kim L., Frieman M., Baric R.A., Palese P. J. Virol. 2007;81:548–557. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01782-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kamitani W., Kim K., Huang C., Lokugamage K., Ikegami T., Ito N., Kubo H., Makino S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:12885–12890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603144103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou H., Kim S. J. Virol. 2007;81:568–574. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01512-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]