Abstract

The Ras effector and E3 ligase family member IMP (impedes mitogenic signal propagation) acts as a steady-state resistor within the Raf-MEK-ERK kinase module. IMP concentrations are directly regulated by Ras, through induction of autoubiquitination, to permit productive Raf-MEK complex assembly. Inhibition of Raf-MEK pathway activation by IMP occurs through the inactivation of KSR, a scaffold/adapter protein that couples activated Raf to its substrate MEK1. The capacity of IMP to inhibit signal propagation through Raf to MEK is, in part, a consequence of disrupting KSR1 homo-oligomerization and c-Raf-B-Raf hetero-oligomerization. These observations suggest that IMP functions as a threshold modulator, controlling sensitivity of the cascade to stimulus by directly limiting the assembly of functional KSR1-dependent Raf-MEK complexes.

The Raf-MEK2-ERK kinase cascade is a fundamental component of both normal and pathological cell regulatory networks. ERK activation ultimately results in modulation of gene transcription, and its amplitude, duration, and subcellular compartmentalization are critical determinants of the biological response (1, 2). Non-catalytic scaffold proteins can generate higher order molecular organization to modulate the assembly, activation, and compartmentalization of MAPK cascades (3–5). Specificity and fidelity may be achieved not only through pre-assembled complexes but also by locally assigning those complexes to distinct receptors or other activators for stimulus-specific induction of the appropriate pathway.

We have described a Ras effector, IMP (impedes mitogenic signal propagation), which negatively regulates ERK activation by limiting formation of Raf-MEK complexes (6). The mechanism of inhibition appears to be through inactivation of KSR1, a scaffold protein that couples activated Raf to its substrate MEK. IMP is a Ras-responsive E3 ubiquitin ligase. Upon Ras activation, IMP is modified by autopolyubiquitination, which relieves its inhibitory effects on KSR. Thus, Ras activates the Raf-MAPK cascade through dual effector interactions: induction of Raf protein kinase activity concomitant with liberation of KSR-dependent Raf-MEK complex assembly. This relationship potentially provides a mechanism to tether MAPK mobilization to appropriate Ras activation thresholds.

Domain Organization and Sequence Conservation of IMP

IMP is a unique protein in terms of its predicted functional domains, domain structure, and high degree of conservation across species. The primary amino acid sequence of IMP predicts a RING-H2 domain, followed by a UBP-ZnF and leucine heptad repeats predicted to form a coiled-coil (SMART, smart.embl-heidelberg.de). This domain architecture is very similar to the RBCC family of proteins that include the proto-oncogenes PML and TIF-1 (7), with the exception of a UBP-ZnF in place of a B-box zinc finger. IMP is the only identifiable protein in the current data bases that has the RING-UBP-ZnF-coiled-coil structure.

The sequential tripartite domain organization of RBCC proteins has been shown to be essential for proper enzymatic function and/or appropriate protein-protein binding events (8). Like many RING-containing molecules, some RBCC proteins such as EFP and MID1 possess E3 ubiquitin ligase activity, whereas PML does not (7). The B-box is important for protein interactions, yet rather than directly taking part in binding, it is believed to orient RING and/or coiled-coil domains for proper associations with other molecules. The coiled-coil domain has been shown to mediate homo- and heterodimerization and, in the case of the Ret finger protein, may contain a nuclear export sequence (9).

The UBP-ZnF motif is found only in DUBs and at least one histone deacetylase, HDAC6. In DUBs, this domain binds ubiquitin (10) and is not required for enzymatic activity. Likewise, in HDAC6, this domain does not affect deacetylase activity and appears to bind polyubiquitin chains (termed the PAZ (polyubiquitin-associated zinc finger) domain) (11). Although this motif may have a common utility in both types of enzymes, it is unexpected in histone deacetylases and is hypothesized to take part in the regulation of heterochromatin assembly (12). IMP is the only protein outside of these two protein families to contain a UBP-ZnF domain. Being that IMP is an E3 ubiquitin ligase, the function of the UBP-ZnF may be as straightforward as binding polyubiquitin for high fidelity chain elongation. In this way, it would act like the UBS (ubiquitin association) domains of E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes or DUBs, which use the domain to associate with polyubiquitin chains during chain elongation or proteolysis, respectively (11).

IMP is highly conserved across eukaryotes, with a single ortholog present in each species. Human multiple-tissue Northern blot analysis shows broad-spectrum expression (6), as described previously in mice (13).

IMP Is an E3 Ubiquitin Ligase

IMP contains a RING-H2 motif that, like many RING-containing proteins (14), exhibits E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. There are two types of E3 ligase, distinguished by their enzymatic domain and mode of ligation (15). The HECT domain E3 enzymes receive activated ubiquitin through an isopeptide linkage that it passes on the target; HECT E3 enzymes are thus true enzymes. RING domain E3 enzymes can function as multiprotein complexes, such as the SCF complex involved in cell cycle regulation, or individual enzymes, such as the tumor suppressors BRCA1 and MDM2 (16). RING domain E3 enzymes simultaneously bind the E2 and target protein and hence facilitate direct ubiquitin transfer by bringing the proteins into spatial proximity. In all organisms, there are only one or two E1 enzymes, tens of E2 enzymes, and hundreds of E3 ligases that selectively interact with particular E2 enzymes; thus, E3 ligases are likely responsible for target selection.

The best evidence of a role for ubiquitin in the ERK cascade comes from studies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, where Ste11 and Ste7 are ubiquitinated upon pheromone induction of the mating response pathway. The RING-containing Ste5 scaffold does not mediate either of these modifications as it does not appear to be a functional E3 ligase. Rather, ubiquitination of Ste7 is mediated by the SCF complex upon Ste11 phosphorylation of Ste7 (17–19). Intriguing work in Dictyostelium suggests a signal-dependent interplay between ubiquitination and sumoylation in the regulation of dDMEK (20). It has also been reported that the PHD domain of MEKK1 has E3 ligase activity and can ubiquitinate ERK in a manner that leads to its degradation (21). Finally, the Ras GTPase-activating protein NF1 may become ubiquitinated upon Ras activation (22).

We could not find any substrates in the ERK cascade for the ubiquitin ligase activity of IMP. However, like most E3 ligases, IMP is likely a true target for its own E3 ligase activity in cells. When combined with recombinant E1 and E2 enzymes, IMP autoubiquitinates, as evidenced the appearance of a “ladder” of higher molecular weight IMP species (6). Ligase activity is eliminated by point mutation of the first cysteine of the RING domain (23); accordingly, the IMP(C264A) mutant does not ladder in the recombinant system (6).

Ras-IMP Interaction

Ras binds IMP in a 104-amino acid region that includes the UBP-ZnF (6). As mentioned, the UBP-ZnF appears to function as a binding domain for polyubiquitin chains in ubiquitin proteases and HDAC6. Although the UBP-ZnF of IMP overlaps with the RBD, UBP-ZnF domains are unlikely to represent a general Ras-binding motif as no other protein containing this domain was isolated in our screens and as Ras failed to interact with the UBP-ZnF (PAZ) domain of HDAC6 in pairwise tests. However, the presence of a zinc finger within the RBD of IMP is reminiscent of Raf, in which the RBD is immediately N-terminal to the zinc finger. The Raf RBD has been shown to be required for Raf recruitment to the plasma membrane, whereas the zinc finger is required for full activation by Ras (24, 25). It is unknown whether there are similar roles for the RBD and UBP-ZnF in IMP.

IMP selectively interacts with Ras in its GTP-bound state, as observed in EGF-stimulated cells (6) and anti-CD3 activated T-cells (26) with overexpressed and native proteins. This interaction stimulates the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of IMP and subsequent autoubiquitination (6). These ubiquitinated IMP species accumulate in mitogen-stimulated cells or cells coexpressing Ras12V and IMP but are not observed in cells expressing the ligase-defective C264A mutant (6). Coexpression of oncogenic Ras with IMP reverses its ability to interfere with MEK activation. Significantly, the C264A mutant restrains oncogenic Ras activation of ERK. This indicates that inactivation of the RING-H2 domain does not impair IMP inhibitory activity but rather turns IMP into a “superinhibitor” that is no longer sensitive to Ras signals.

Threshold Control

Ectopic expression of IMP blocks activation of the ERK cascade between Raf and MEK. Hypomorphic studies (described below) have shown that this is not simply an artifact of overexpression. Transcriptional activation through ERK is likewise inhibited, as shown in reporter assays with Elk-1 (26), c-Fos (6), and NF-AT (26). The inhibitory function of IMP appears to be specific for the ERK pathway as other kinases such as JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase) and Akt are not affected (6).

Inhibition of native IMP expression increases the amplitude of ERK pathway activation without alterations in the timing or duration of the response. The dynamic range of ERK activation is known to be important for the determination of various cells fates, with drastically different phenotypes driven by the lower versus higher range of activation. “Strong” ERK activation can promote cell cycle arrest in fibroblasts (27–29), differentiation of PC12 cells (30, 31), and survival of carcinoma cells (32). Conversely, “weak” ERK activation can result in proliferation of fibroblasts (27–29) and PC12 cells (30, 31) and apoptosis in carcinoma cells (33, 34). The magnitude of ERK activation is also responsible for various outcomes in the selection and specification of certain T-cell populations (35, 36). Depletion of IMP protein does not affect base-line activation of MEK and ERK (6) but rather elevates their response to mitogenic stimulation and cross-linking of the T-cell receptor complex (26). Similarly, IMP-depleted PC12 cells are sensitized to nerve growth factor such that neurite outgrowth is induced at normally subthreshold concentrations (6). Finally, inhibition of IMP expression has been shown to significantly increase cytokine production by human Jurkat T-cells and primary mouse CD4 T-cells upon engagement of the T-cell receptor complex (26). Thus, IMP functions as a signal threshold regulator for the ERK pathway by imposing a stimulus-responsive inhibitory mechanism that must itself be inhibited for signal transduction to occur.

This concept is interesting in light of the recently described “model-breakpoint analysis,” which demonstrates that the best predictor of signal-induced cell phenotypes is the dynamic range over which signaling occurs rather than the size of the basal or maximal signal (37). By coupling signal throughput to IMP protein concentration, the dynamic range of Ras signaling can be fine-tuned within “normal” parameters to fit a given physiological situation. It would be interesting to examine the model breakpoint of IMP inhibition of ERK signaling in the presence and absence of constitutively active Ras12V and how it changes with expression of ligase-defective IMP.

KSR Scaffolding of Raf-MEK

A preponderance of genetic, cell biological, and biochemical evidence indicates that KSR1 is a necessary mediator of functional Raf-MEK complex formation (38, 39). IMP interacts with KSR1 and requires its expression to influence MEK activation (6, 40). The mechanism by which KSR1 promotes Raf-MEK coupling is not completely understood but most likely involves direct binding to both Raf and MEK.

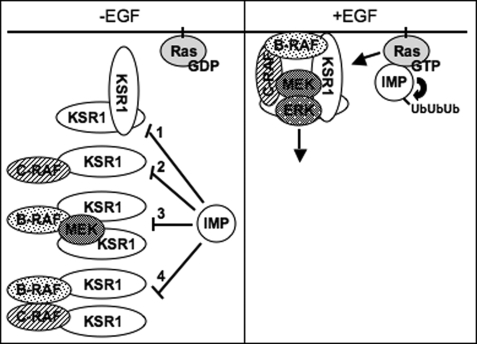

The inhibitory action of IMP on Raf-MEK complex formation is explained at least in part by its effects on KSR homo-oligomerization. KSR1 proteins can homo-oligomerize through interactions in the C-terminal half, and IMP expression blocks this interaction (40). This may occur in part through direct interactions between IMP and KSR as they associate via their respective N-terminal halves (6). Interestingly, IMP exists in KSR1 complexes containing endogenous MEK but not in those containing B-Raf, suggesting that there are multiple KSR-MEK activation complex intermediates that are selectively modulated by IMP (40). In fact, IMP expression can impair the oligomerization of KSR1-MEK and KSR1-B-Raf complexes to limit the accessibility of MEK for activation by B-Raf. Although IMP expression blocks KSR1 homo-oligomerization without affecting the interaction of KSR1 with MEK1 or B-Raf, this has significant consequences on the ability of Raf to activate MEK and thus propagate signals through the pathway (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

IMP impedes Ras mitogenic signaling by limiting KSR1 complexes. In the absence of mitogen, IMP blocks KSR1 C-terminal homo-oligomerization (Step 1), KSR1-c-Raf binding (Step 2), B-Raf-MEK binding without affecting their association with KSR1 (Step 3), and B-Raf-c-Raf hetero-oligomerization (Step 4). Upon stimulation, Ras-GTP binds IMP and activates its autoubiquitination, thus relieving signal inhibition. Concomitantly, Ras-GTP activates Raf and allows subsequent KSR1 complex formation and ERK pathway signaling.

There are likely distinct complexes of KSR1-MEK, KSR1-c-Raf, and KSR1-B-Raf in cells, and pathway activation appears to require KSR1 homo-oligomerization to join Raf with its substrate. This has been demonstrated in Drosophila cells, in which dKSR promoted dRaf-mediated dMEK phosphorylation only if it could bind dRaf and dMEK individually; dRas activity was not required for dRaf and dKSR to interact (41). Furthermore, co-localization of dKSR and dRaf was sufficient to activate dMEK in quiescent cells and in transgenic flies (41). Likewise, we found that EGF-induced B-Raf-c-Raf complexes were undetectable in KSR1-null mouse embryo fibroblasts but were restored upon re-expression of KSR1 at near physiological concentrations (40). Thus, in addition to promoting Raf-MEK complex assembly, KSR1 promotes c-Raf-B-Raf hetero-oligomerization. This suggests that, like the Drosophila ortholog, human KSR1 acts both upstream and downstream of Raf kinase activation.

KSR Scaffolding of c-Raf-B-Raf

Recently, c-Raf-B-Raf hetero-oligomerization has been revealed as an essential step for maximal c-Raf kinase activation and is required for biological responses to low activity B-Raf variants in melanomas (42, 43). Although it is still unclear how c-Raf-B-Raf heterodimerization triggers c-Raf activation, B-Raf kinase activity is surprisingly not required as kinase-inactive B-Raf can still promote activation of the c-Raf catalytic domain (40). This suggests that association with B-Raf either facilitates activating c-Raf transphosphorylation or recruits additional upstream regulators that promote c-Raf kinase activation.

Interestingly, IMP has differential effects on the engagement of c-Raf versus B-Raf for mitogenic signaling (40). In addition to blocking KSR-mediated c-Raf-B-Raf hetero-oligomerization, IMP reverses the ability of kinase-dead B-Raf to increase the specific activity of the c-Raf catalytic domain. Depletion of IMP by RNA interference increased the level of detectable EGF-stimulated B-Raf/c-Raf heterodimers. Thus, IMP is both necessary and sufficient to limit generation of active B-Raf-c-Raf protein complexes. This inhibition does not appear to affect binding of 14-3-3, which has been suggested to be a prerequisite for c-Raf-B-Raf association (43). Although IMP does not affect the KSR1-B-Raf association, IMP does uncouple c-Raf from KSR1 complexes. The uncoupling of c-Raf from KSR1 appears to be critical to the inhibitory effects of IMP on MEK. This is suggested by experiments in which the remaining active MEK in EGF-stimulated cells depleted of c-Raf by RNA interference was insensitive to overexpression of IMP (40). Also, the enhanced MEK activation normally observed upon IMP depletion was reversed by co-depletion of c-Raf.

Like its effect on B-Raf, IMP inhibits Raf-1 activation of MEK without blocking Raf-1 activation (6). In response to EGF stimulation, Raf-1 is phosphorylated at Ser338 (44). This is an activating phosphorylation that occurs upon Ras association (25) and is required for Raf kinase activity (44). IMP expression does not inhibit stimulus-dependent phosphorylation of Ser338; on the contrary, the phosphorylation is enhanced. Considering that IMP blocks ERK activation, this is likely a consequence of uncoupling negative feedback inhibition of EGF signaling.

Regulation of KSR

Work by Morrison and co-workers (45, 46) and Lewis and co-workers (47, 48) has provided key information about how KSR1 is regulated by phosphorylation, subcytoplasmic partitioning, and nucleocytoplasmic shuttling. KSR is constitutively associated with MEK and interacts with ERK in a stimulus-dependent fashion (45). Both kinases bind KSR1 directly at the CA3 domain, which contains a possible ERK-docking site (FXFP) (45). In normal unstimulated cells, KSR1 is sequestered in the cytoplasm via association with a 14-3-3 protein dimer bound to phosphoserines (46). Upon stimulation, protein phosphatase 2A dephosphorylates the c-TAK phosphorylation site (Ser392), causing the dissociation of 14-3-3. This allows KSR-MEK to translocate to the plasma membrane, the site of active Raf. Interestingly, substitution of serine for alanine at position 392 maintains KSR at the plasma membrane and promotes ERK binding and Ras signaling on its own, thus sensitizing the pathway to stimulation (46). These data provide insight into how scaffolds may be regulated and underscore the importance of controlling the intracellular location of multiprotein complexes. KSR is also phosphorylated on multiple sites in cells in a mitogen-dependent manner (47).

IMP has effects on KSR1 that mimic a loss-of-function variant (C809Y) discovered in a Ras suppressor screen in Caenorhabditis elegans. C809Y is hyperphosphorylated, fails to associate with MEK, and partitions to a distinct biochemical compartment (49). Although IMP does not interfere with KSR-MEK binding, it does promote hyperphosphorylation of KSR1 and partitioning to the same distinct cellular fraction as C809Y (6). Furthermore, immunofluorescence analysis revealed that IMP recruits KSR to distinct subcellular compartments, which is reversed upon Ras activation (6). Interestingly, IMP that has been modified with a CAAX motif (and is thus localized to the cell membrane) is an even more effective ERK pathway inhibitor than unmodified IMP; the CAAX effect is further enhanced in the IMP(C264A) mutant (26). This may suggest that the site of action of IMP is near the membrane, which is consistent with its roles in suppressing membrane localization of KSR1 complexes and as a Ras effector. Interestingly, expression of IMP-CAAX in cells depleted of endogenous IMP inhibits ERK signals better that IMP-CAAX expressed in cells with normal endogenous IMP levels (26). This may suggest that endogenous autoubiquitinated IMP contributes to positive ERK signaling. Although IMP blocks the ability of ectopically expressed KSR to enhance ERK activation, it cannot inhibit mitogen-stimulated ERK activation in KSR-null cells (6). Together, these observations suggest that KSR is required for IMP to modulate ERK activity and that IMP functions to hold a pool of KSR in an inactive state.

Conclusion

The capacity of signaling molecules to respond appropriately to dynamic extracellular environments likely requires coupling to a physiologically relevant response threshold. The presence of proteins like IMP may provide a mechanism to impose flexibility in the position of such thresholds in response to the complexity of external stimuli. Like a rheostat, the position of the threshold may be modulated by IMP regulators and be held by IMP. In this way, the action of IMP may prevent ultrasensitivity of MAPK pathway activation and maximize the dynamic range of Ras-dependent signals that can engage pathway activation.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant CA71443. This work was also supported by Robert Welch Foundation Grant I-1414. This is the third article of three in the Thematic Minireview Series on Novel Ras Effectors. This minireview will be reprinted in the 2009 Minireview Compendium, which will be available in January, 2010.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; UBP-ZnF, ubiquitin protease-like zinc finger; RBCC, RING B-box coiled-coil; DUBs, deubiquitinating enzymes; RBD, Ras-binding domain; EGF, epidermal growth factor.

References

- 1.Raman, M., Chen, W., and Cobb, M. H. (2007) Oncogene 26, 3100–3112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitehurst, A., Cobb, M. H., and White, M. A. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 10145–10150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bumeister, R., Rosse, C., Anselmo, A., Camonis, J., and White, M. A. (2004) Curr. Biol. 14, 439–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrison, D. K., and Davis, R. J. (2003) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 19, 91–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kolch, W. (2005) Nat. Rev. 6, 827–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matheny, S. A., Chen, C., Kortum, R. L., Razidlo, G. L., Lewis, R. E., and White, M. A. (2004) Nature 427, 256–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jensen, K., Shiels, C., and Freemont, P. S. (2001) Oncogene 20, 7223–7233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meroni, G., and Diez-Roux, G. (2005) BioEssays 27, 1147–1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harbers, M., Nomura, T., Ohno, S., and Ishii, S. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 48596–48607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reyes-Turcu, F. E., Horton, J. R., Mullally, J. E., Heroux, A., Cheng, X., and Wilkinson, K. D. (2006) Cell 124, 1197–1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hurley, J. H., Lee, S., and Prag, G. (2006) Biochem. J. 399, 361–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyault, C., Gilquin, B., Zhang, Y., Rybin, V., Garman, E., Meyer-Klaucke, W., Matthias, P., Muller, C. W., and Khochbin, S. (2006) EMBO J. 25, 3357–3366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li, S., Ku, C. Y., Farmer, A. A., Cong, Y. S., Chen, C. F., and Lee, W. H. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 6183–6189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joazeiro, C. A., and Weissman, A. M. (2000) Cell 102, 549–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pickart, C. M. (2001) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70, 503–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fang, S., Jensen, J. P., Ludwig, R. L., Vousden, K. H., and Weissman, A. M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 8945–8951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esch, R. K., and Errede, B. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99, 9160–9165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang, Y., and Dohlman, H. G. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 15766–15772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang, Y., Ge, Q., Houston, D., Thorner, J., Errede, B., and Dohlman, H. G. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 22284–22289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sobko, A., Ma, H., and Firtel, R. A. (2002) Dev. Cell 2, 745–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu, Z., Xu, S., Joazeiro, C., Cobb, M. H., and Hunter, T. (2002) Mol. Cell 9, 945–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cichowski, K., Santiago, S., Jardim, M., Johnson, B. W., and Jacks, T. (2003) Genes Dev. 17, 449–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ota, S., Hazeki, K., Rao, N., Lupher, M. L., Jr., Andoniou, C. E., Druker, B., and Band, H. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 414–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo, Z., Diaz, B., Marshall, M. S., and Avruch, J. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 46–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roy, S., Lane, A., Yan, J., McPherson, R., and Hancock, J. F. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 20139–20145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Czyzyk, J., Chen, H. C., Bottomly, K., and Flavell, R. A. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 23004–23015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coleman, M. L., Marshall, C. J., and Olson, M. F. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 2036–2046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woods, D., Parry, D., Cherwinski, H., Bosch, E., Lees, E., and McMahon, M. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 5598–5611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sewing, A., Wiseman, B., Lloyd, A. C., and Land, H. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 5588–5597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vaudry, D., Stork, P. J., Lazarovici, P., and Eiden, L. E. (2002) Science 296, 1648–1649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Santos, S. D., Verveer, P. J., and Bastiaens, P. I. (2007) Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 324–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vial, E., and Marshall, C. J. (2003) J. Cell Sci. 116, 4957–4963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Persons, D. L., Yazlovitskaya, E. M., Cui, W., and Pelling, J. C. (1999) Clin. Cancer Res. 5, 1007–1014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yazlovitskaya, E. M., Pelling, J. C., and Persons, D. L. (1999) Mol. Carcinog. 25, 14–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McNeil, L. K., Starr, T. K., and Hogquist, K. A. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102, 13574–13579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lovatt, M., Filby, A., Parravicini, V., Werlen, G., Palmer, E., and Zamoyska, R. (2006) Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 8655–8665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Janes, K. A., Reinhardt, H. C., and Yaffe, M. B. (2008) Cell 135, 343–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Claperon, A., and Therrien, M. (2007) Oncogene 26, 3143–3158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morrison, D. K. (2001) J. Cell Sci. 114, 1609–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen, C., Lewis, R. E., and White, M. A. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 12789–12796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roy, F., Laberge, G., Douziech, M., Ferland-McCollough, D., and Therrien, M. (2002) Genes Dev. 16, 427–438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wan, P. T., Garnett, M. J., Roe, S. M., Lee, S., Niculescu-Duvaz, D., Good, V. M., Jones, C. M., Marshall, C. J., Springer, C. J., Barford, D., and Marais, R. (2004) Cell 116, 855–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garnett, M. J., Rana, S., Paterson, H., Barford, D., and Marais, R. (2005) Mol. Cell 20, 963–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Edin, M. L., and Juliano, R. L. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 4466–4475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muller, J., Ory, S., Copeland, T., Piwnica-Worms, H., and Morrison, D. K. (2001) Mol. Cell 8, 983–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ory, S., Zhou, M., Conrads, T. P., Veenstra, T. D., and Morrison, D. K. (2003) Curr. Biol. 13, 1356–1364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Razidlo, G. L., Kortum, R. L., Haferbier, J. L., and Lewis, R. E. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 47808–47814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brennan, J. A., Volle, D. J., Chaika, O. V., and Lewis, R. E. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 5369–5377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stewart, S., Sundaram, M., Zhang, Y., Lee, J., Han, M., and Guan, K. L. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 5523–5534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]