A new and deadly clinical syndrome now called severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) was brought to the attention of the WHO by Dr. Carlo Urbani and his colleagues in a Vietnamese hospital in February 2003 (1). The WHO, the medical staffs in hospitals where the disease had appeared, and local and regional governments, together with a dozen cooperating laboratories across the globe, immediately responded. They provided a provisional case definition to identify the extent and geographic distribution of the outbreak (2), laboratory investigations to identify the infectious agent, and travel advisories and quarantines to limit the spread of the disease (3, 4). This extraordinary and effective collaboration limited the potentially explosive spread of the outbreak, while initial case reports with clinical and epidemiological information were quickly posted on the Internet to help physicians identify additional cases of the new syndrome (2, 4–9). The press and scientific journals played valuable roles in rapidly distributing accurate information about SARS to the frightened public and making key scientific publications about SARS available via the Internet before they could appear in print. A stroke of good fortune in this crisis was the discovery that a novel virus could be readily isolated from patients’ lungs and sputum and cultivated in a monkey kidney cell line (8, 10, 11). Laboratory investigations using electron microscopy, virus-discovery microarrays containing conserved nucleotide sequences characteristic of many virus families, randomly primed RT-PCR, and serological tests quickly identified the virus as a new coronavirus (8, 10, 11). Inoculation of monkeys with the SARS-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) caused interstitial pneumonia resembling SARS, and the virus was isolated from the nose and throat (12). No viral or bacterial copathogen was needed to induce the disease. These experiments fulfilled Koch’s postulates and proved that SARS-CoV is the cause of SARS.

Lessons from the pathophysiology and epidemiology of known coronavirus diseases of humans and animals

Until SARS appeared, human coronaviruses were known as the cause of 15–30% of colds (13). Because there is no small-animal model for coronavirus colds, the pathophysiology of human coronavirus infection of the upper respiratory tract was studied in human volunteers (14, 15). Intranasal inoculation induces colds in a small percentage of volunteers, although virus replication in nasal epithelium is detected in most volunteers. Colds are generally mild, self-limited infections, and significant increases in neutralizing antibody titer are found in nasal secretions and serum after infection. Nevertheless, some unlucky individuals can be reinfected with the same coronavirus soon after recovery and get symptoms again. Coronavirus colds are more frequent in winter, and the two known human coronaviruses vary in prevalence from year to year. If SARS becomes established in humans, will it also have a seasonal incidence of clinical disease? Prospective studies of hospitalized patients showed that human respiratory coronaviruses only rarely cause lower respiratory tract infection, perhaps in part because they grow poorly at 37°C. Although coronavirus-like particles have been observed by electron microscopy in human feces, and serological studies of necrotizing enterocolitis in infants occasionally show rises in antibody titer to coronaviruses (16–18), infectious human coronaviruses have been, until SARS, extremely difficult to isolate from feces (19).

Coronaviruses cause economically important diseases of livestock, poultry, and laboratory rodents (20). Most coronaviruses of animals infect epithelial cells in the respiratory and/or enteric tracts, causing epizootics of respiratory diseases and/or gastroenteritis with short incubation periods (2–7 days), such as those found in SARS. In general, each coronavirus causes disease in only one animal species. In immunocompetent hosts, infection elicits neutralizing antibodies and cell-mediated immune responses that kill infected cells. In SARS patients, neutralizing antibodies are detected 2–3 weeks after the onset of disease, and 90% of patients recover without hospitalization (10). In animals, reinfection with coronaviruses is common, with or without disease symptoms. The duration of shedding of SARS-CoV from respiratory secretions of SARS patients appears to be quite variable. Some animals can shed infectious coronavirus persistently from the enteric tract for weeks or months without signs of disease, transmitting infectious virus to neonates and other susceptible animals. SARS-CoV has been detected in the feces of patients by RT-PCR and virus isolation (8, 11). Studies are being done to learn whether SARS-CoV is shed persistently from the respiratory and/or enteric tracts of some humans without signs of disease. Host factors such as age, strain or genotype, immune status, coinfection with other viruses, bacteria, or parasites, and stress affect susceptibility to coronavirus-induced diseases of animals, and the ability to spread virus to susceptible animals. It is important to learn what host factors and/or virus differences are responsible for the “super-spreader” phenomenon observed in SARS, in which a few patients infect many people through brief casual contact or possibly environmental contamination, even though most patients infect only people in close contact with them during the period of overt disease.

Several coronaviruses can cause fatal systemic diseases in animals, including feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV), hemagglutinating encephalomyelitis virus (HEV) of swine, and some strains of avian infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) and mouse hepatitis virus (MHV). These coronaviruses can replicate in liver, lung, kidney, gut, spleen, brain, spinal cord, retina, and other tissues. SARS-CoV has been found in patients’ lungs, feces, and kidney. Further studies with sensitive methods of detection will reveal which additional tissues may be infected with SARS-CoV. The pathophysiology of coronavirus diseases of animals has been studied extensively, but there is no coronavirus disease of animals that closely resembles SARS. Immunopathology plays a role in tissue damage in MHV and FIPV, and cytokines are responsible for some signs of disease. Significantly, in cats with persistent, inapparent infection with feline enterotropic coronavirus, virulent virus mutants can arise and cause fatal infectious peritonitis, a systemic disease (21). Are virulent mutants of SARS-CoV associated with the fatal cases? Comparison of the genomes of SARS-CoVs isolated from fatal versus milder cases will identify any virus mutations that may be associated with increased virulence.

In animals, coronaviruses cause enzootic or epizootic diseases. Four different coronaviruses infect pigs, and the epidemiology of these porcine diseases is informative. Transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus (TGEV) can infect the enteric and respiratory tracts, causing severe diarrhea in suckling pigs, and milder or inapparent infection in adult pigs. Mutant TGEVs with spontaneous deletions of more than 200 amino acids in the viral spike glycoprotein, or several point mutations in the same region, have arisen separately in Europe and the US and are called porcine respiratory coronavirus (PRCoV). The mutant viruses cause mild respiratory disease and cannot infect the gut (22). PRCoV may serve as a natural vaccine to protect piglets from TGEV. A third porcine coronavirus, HEV, causes vomiting and wasting disease of piglets and can cause encephalomyelitis. A “new” porcine coronavirus, porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV), was first detected in European pigs during widespread outbreaks of fatal diarrhea of piglets during the 1980s (23). Serology suggests that, before this time, pigs had not been exposed to PEDV. How do such “new” coronaviruses emerge? What viral or host factors make them able to spread so effectively?

How did SARS-CoV suddenly appear in humans?

Human sera collected before the SARS outbreak do not contain antibodies directed against SARS-CoV (8, 10), suggesting that this virus is new to humans. Additional studies on human sera from the region where the outbreak began are needed to confirm this preliminary finding. Did SARS-CoV jump to humans by mutation of an animal coronavirus or by recombination between several known human or animal coronaviruses?

The complete 29,727-nucleotide sequence of the RNA genome of SARS-CoV (GenBank accession nos. AY274119 and AY278741) (24, 25) proves that it is a member of the Coronaviridae family and provides some insight into its possible origin. The SARS-CoV genome encodes all five of the coronavirus proteins needed for production of new virions. It contains the enormous (20-kb) gene that encodes the unique RNA-dependent RNA polymerase common to all coronaviruses. The order of the genes encoding the RNA polymerase and structural proteins is conserved in the genomes of all coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV. Interspersed between these genes are several nonconserved open reading frames encoding proteins that are not required for virus replication. The SARS genome, like that of other coronaviruses, contains several nonconserved, open reading frames that encode small nonstructural proteins with unknown functions.

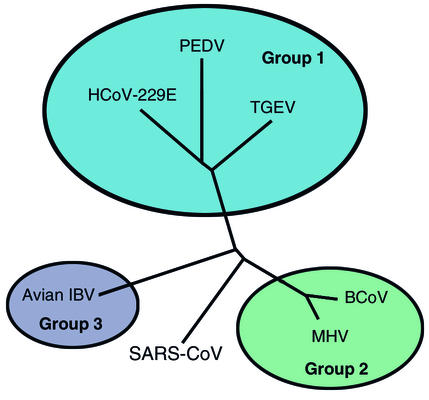

The genes of SARS-CoV were compared with the corresponding genes of known coronaviruses of humans, pigs, cattle, dogs, cats, mice, rats, chickens, and turkeys. Each gene of SARS-CoV has only 70% or less identity with the corresponding gene of the known coronaviruses. Thus, SARS-CoV is only distantly related to the known coronaviruses of humans and animals. Phylogenetic analysis (Figure 1) suggests that SARS-CoV does not fit within any of the three groups that contain all other known coronaviruses (11, 24, 25). Its closest relatives are the murine, bovine, porcine, and human coronaviruses in group 2 and avian coronavirus IBV in group 1. These data show that SARS-CoV did not arise by mutation of human respiratory coronaviruses or by recombination between known coronaviruses. Instead, it is likely that SARS-CoV was enzootic in an unknown animal or bird species and had been genetically isolated there for a very long time before somehow suddenly emerging as a virulent virus of humans. Did this jump to humans occur only once because of an unlucky and unlikely combination of random mutations, or can SARS-CoV now infect both humans and its original host? Does the virus have the potential to jump repeatedly from its animal host to cause deadly outbreaks of human disease?

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of coronaviruses, based on the polymerase gene, shows that SARS coronavirus is different from each of the three groups of the previously known coronaviruses. HCoV-229E, human coronavirus 229E; BCoV, bovine coronavirus. Adapted with permission from ref. 24.

What features of SARS-CoV and its replication are potential targets for development of new antiviral drugs and vaccines?

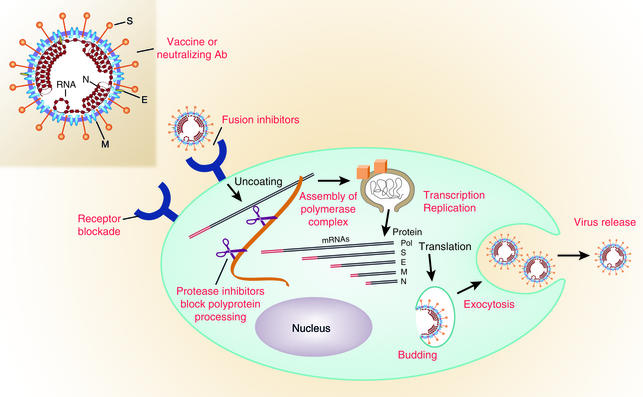

Unfortunately, there are no approved antiviral drugs that are highly effective against coronaviruses. However, many steps unique to coronavirus replication could be targeted for development of antiviral drugs (Figure 2). Coronavirus infection begins with binding of the spike protein (S) on the viral envelope to a specific receptor on the cell membrane. Conformational changes are induced in S that probably lead to fusion of the viral envelope with the host cell membrane (23–25). Molecules that block binding to the receptor or inhibit the receptor-induced conformational change in S might block SARS-CoV infection (26–28). Inhibitors of HIV-1 entry and membrane fusion are good models for new drugs that target this first step in coronavirus infection.

Figure 2.

Steps in coronavirus replication that are potential targets for antiviral drugs and vaccines. The spike glycoprotein S is a good candidate for vaccines because neutralizing antibodies are directed against S. Blockade of the specific virus receptor on the surface of the host cell by monoclonal antibodies or other ligands can prevent virus entry. Receptor-induced conformational changes in the S protein can be blocked by peptides that inhibit membrane fusion and virus entry. The polyprotein of the replicase protein is cleaved into functional units by virus-encoded proteinases. Protease inhibitors may block replication. The polymerase functions in a unique membrane-bound complex in the cytoplasm, and the assembly and functions of this complex are potential drug targets. Viral mRNAs made by discontinuous transcription are shown in the cytoplasm with the protein that each encodes indicated at the right. The common 70 base long leader sequence on the 5′ end of each mRNA is shown in red. Budding and exocytosis are processes essential to virus replication that may be targets for development of antiviral drugs. M, membrane protein required for virus budding; S, viral spike glycoprotein that has receptor binding and membrane fusion activities; E, small membrane protein that plays a role in coronavirus assembly; N, nucleocapsid phosphoprotein associated with viral RNA inside the virion. Adapted with permission from ref. 35.

The large polyprotein encoded by the polymerase gene of coronaviruses must be proteolytically cleaved at specific sites by several virus-encoded proteases in order to have RNA polymerase activity (29–31). Protease inhibitors developed to treat other viral diseases as well as new protease inhibitors are being tested for the ability to inhibit cleavage of the SARS-CoV polymerase protein and viral RNA synthesis. Coronavirus RNA is synthesized in a virus-specific, flask-shaped cytoplasmic compartment bordered by a double membrane (32). Could the assembly or function of this unique organelle be inhibited?

The RNA genome of coronaviruses is transcribed discontinuously so that the complement of the 70-nucleotide leader sequence is joined to the 3′ ends of the subgenomic negative-strand RNAs that are templates for the nested set of subgenomic mRNAs (33, 34). Perhaps a small RNA or other inhibitor could be designed to block this unusual discontinuous RNA transcription. Alternatively, nucleoside inhibitors might be designed to block SARS-CoV replication specifically without damaging the cell.

Coronavirus structural proteins and newly synthesized RNA genomes assemble into virions by budding into pre-Golgi membranes. Virus assembly is also a potential target for drug development. Coronaviruses are apparently released from living cells by exocytosis, so inhibitors of secretion should be tested for antiviral activity.

The spike glycoproteins on virions of several coronaviruses require cleavage by serine protease to activate viral infectivity, but it is not yet known whether this is also true for SARS-CoV. Inhibitors of serine proteases might block this late step in the coronavirus life cycle.

Fortunately, new antiviral drugs that will be developed to treat SARS-CoV may also be effective in the treatment of common colds and economically important coronavirus diseases of companion animals, livestock, and poultry. Antiviral drugs to treat other diseases of the respiratory tract, such as influenza, are most effective when used very soon after signs of disease appear. If this is also found to be true for antiviral drugs for SARS, then rapid viral diagnostic tests will be needed to differentiate SARS from other pulmonary infections soon after the onset of disease.

In about 10% of SARS patients, interstitial pneumonia is followed after 5–7 days by progressive diffuse alveolar damage, possibly due to immunopathology (5, 8–10). Corticosteroids have been used to try to reduce disease progression. When the pathophysiology of these severe cases of SARS is understood, more specific anti-inflammatory drugs may be found to prevent SARS-induced progressive tissue damage. If specific host factors are found to be associated with the most severe cases, it may be possible to modulate their expression or activity in order to prevent progression of the disease. If host factors play a role in SARS progression, a test to identify patients with the highest risk of severe SARS might guide decisions concerning potential benefits versus risks of the use of novel antiviral drugs and other treatments.

Passive immunization with convalescent serum has been tested as a way to treat SARS. A possible approach for prevention of SARS in people at high risk of exposure, such as health care workers, is administration of neutralizing mAb’s against the spike protein of SARS-CoV, similar to the current use of a neutralizing mAb against respiratory syncytial virus to prevent lower respiratory tract disease in infants at high risk of complications. Such a neutralizing anti-SARS mAb might also be useful for treatment of SARS.

Control of SARS is most likely to be achieved by vaccination. Live attenuated vaccines prevent serious diseases caused by porcine and avian coronaviruses. It is likely that a similar live attenuated vaccine could be developed for SARS-CoV, especially since the virus can be grown to high titers in cell culture. It will be particularly important to test SARS vaccines for untoward effects, however, since several vaccines against feline coronavirus have caused antibody-dependent enhancement of disease when the vaccinated animals were subsequently infected with wild-type virus. A SARS vaccine would be used to protect health care workers and others at high risk in areas where the virus is circulating. However, because the incubation period of SARS is so short, the vaccine would have to be used prophylactically, and it would be unlikely to prevent disease when used after exposure to a SARS patient.

The SARS epidemic appears to be out of control now in some areas. New tests to identify SARS patients at the earliest stages of disease are expected to be widely available soon. These tests will guide quarantine decisions and other public health measures to limit the spread of infection. Nevertheless, it now appears likely that drugs and/or vaccines will be needed to control the epidemic. Development of effective drugs and vaccines for SARS is likely to take a long time. The world will anxiously watch the high-stakes race between the spread of the SARS epidemic and the development of effective SARS drugs and vaccines.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The author has declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Nonstandard abbreviations used: severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS); SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV); feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV); hemagglutinating encephalomyelitis virus (HEV); infectious bronchitis virus (IBV); mouse hepatitis virus (MHV); transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus (TGEV); porcine respiratory coronavirus (PRCoV); porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV).

References

- 1.2003. World Health Organization. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): multi-country outbreak. http://www.who.int/csr/don/2003_03-16/en/.

- 2.Preliminary clinical description of severe acute respiratory syndrome. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2003;52:255–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO recommended measures for persons undertaking international travel from areas affected by severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 2003;78:97–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerberding, J.L. 2003. Faster. But fast enough? Responding to the epidemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Lee, N., et al. 2003. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N. Engl. J. Med. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Poutanen, S.M., et al. 2003. Identification of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Canada. N. Engl. J. Med. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Tsang, K.W., et al. 2003. A cluster of cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N. Engl. J. Med. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Peiris JSM, et al. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1319–1325. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan-Yeung M, Yu WC. Outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong Special Administrative Region: case report. BMJ. 2003;326:850–852. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7394.850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ksiazek, T.G., et al. 2003. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Drosten, C., et al. 2003. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Fouchier RAM, et al. Aetiology: Koch’s postulates fulfilled for SARS virus. Nature. 2003;423:240. doi: 10.1038/423240a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holmes, K.V. 2001. Coronaviruses. In Fields’ virology. D. Knipe, et al., editors. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. 1187–1203.

- 14.Bradburne AF, Tyrrell DAJ. Coronaviruses of man. Prog. Med. Virol. 1971;13:373–403. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chilvers MA, et al. The effects of coronavirus on human nasal ciliated respiratory epithelium. Eur. Respir. J. 2001;18:965–970. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.00093001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Resta S, Luby JP, Rosenfeld CR, Siegel JD. Isolation and propagation of a human enteric coronavirus. Science. 1985;229:978–981. doi: 10.1126/science.2992091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kapikian AZ. The coronaviruses. Dev. Biol. Stand. 1975;28:42–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Battaglia M, Passarani N, Di Matteo A, Gerna G. Human enteric coronaviruses: further characterization and immunoblotting of viral proteins. J. Infect. Dis. 1987;155:140–143. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.1.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Macnaughton MR, Davies HA. Human enteric coronaviruses: brief review. Arch. Virol. 1981;70:301–313. doi: 10.1007/BF01320245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai, M.M.C., and Holmes, K.V. 2001. Coronaviridae and their replication. In Fields’ virology. D. Knipe, et al., editors. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. 1163–1185.

- 21.Herrewegh AA, et al. Persistence and evolution of feline coronavirus in a closed cat-breeding colony. Virology. 1997;234:349–363. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ballesteros ML, Sanchez CM, Enjuanes L. Two amino acid changes at the N-terminus of transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus spike protein result in the loss of enteric tropism. Virology. 1997;227:378–388. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.8344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Arriba ML, Carvajal A, Pozo J, Rubio P. Mucosal and systemic isotype-specific antibody responses and protection in conventional pigs exposed to virulent or attenuated porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2002;85:85–97. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(01)00417-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rota, P.A., et al. 2003. Characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science. doi:10.1126/science.1085952. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Marra, M.A., et al. 2003. The genome sequence of the SARS-associated coronavirus. Science. doi:10.1126/science.1085953. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Matsuyama S, Taguchi F. Receptor-induced conformational changes of murine coronavirus spike protein. J. Virol. 2002;76:11819–11826. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.23.11819-11826.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zelus BD, Schickli JH, Blau DM, Weiss SR, Holmes KV. Conformational changes in the spike glycoprotein of murine coronavirus are induced at 37C either by soluble murine CEACAM1 receptors or by pH 8. J. Virol. 2003;77:830–840. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.2.830-840.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewicki DN, Gallagher TM. Quaternary structure of coronavirus spikes in complex with carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule cellular receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:19727–19734. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201837200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ziebuhr J, Siddell SG. Processing of the human coronavirus 229E replicase polyproteins by the virus-encoded 3C-like proteinase: identification of proteolytic products and cleavage sites common to pp1a and pp1ab. J. Virol. 1999;73:177–185. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.177-185.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Denison MR, et al. The putative helicase of the coronavirus mouse hepatitis virus is processed from the replicase gene polyprotein and localizes in complexes that are active in viral RNA synthesis. J. Virol. 1999;73:6862–6871. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6862-6871.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hegyi A, Ziebuhr J. Conservation of substrate specificities among coronavirus main proteases. J. Gen. Virol. 2002;83:595–599. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-3-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gosert R, Kanjanahaluethai A, Egger D, Bienz K, Baker SC. RNA replication of mouse hepatitis virus takes place at double-membrane vesicles. J. Virol. 2002;76:3697–3708. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.8.3697-3708.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sawicki D, Wang T, Sawicki S. The RNA structures engaged in replication and transcription of the A59 strain of mouse hepatitis virus. J. Gen. Virol. 2001;82:385–396. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-2-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sethna PB, Brian DA. Coronavirus genomic and subgenomic minus-strand RNAs copartition in membrane-protected replication complexes. J. Virol. 1997;71:7744–7749. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7744-7749.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.1996. Fundamental Virology. B.N. Fields, D.M. Knipe, and P.M. Howley, editors. 3rd edition. Lippincott-Raven. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA/New York, New York, USA. 544.