Four years ago, Facebook announced that they were decamping to Menlo Park from their longstanding home of Palo Alto. Just last month, the company finally cut the ribbons on a beautiful 430,000-square foot building designed by Frank Gehry that is basically one giant, open-air room with an enormous park on top.

The effect on the prices of surrounding real estate has been profound.

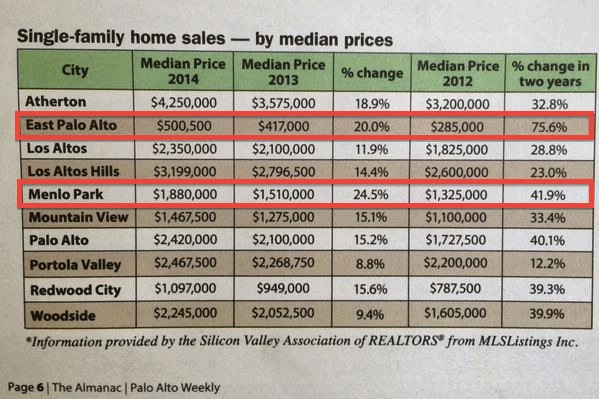

If you look at the chart below, published last week in the Almanac and Palo Alto Weekly, the price increases are mainly concentrated in Menlo Park and the neighboring city of East Palo Alto.

East Palo Alto is a historically black and now majority Latino community that took shape more than half a century ago through a legacy of racially discriminatory practices in Bay Area housing markets. Given that it is the most affordable community left in Silicon Valley, the city’s economy also supplies low-wage labor to the neighboring affluent suburbs of Palo Alto, Menlo Park and Atherton. It has a resilient, but sometimes painful history.

An East Palo Alto musician named Freddy Lopez and a group of teenagers from the neighborhood recently made the music video and documentary above about what it’s like to constantly live in fear of being priced out of the community you’ve always known. (Some of them are affiliated with Live in Peace, the non-profit that Facebook chief product officer Chris Cox backed with $1 million earlier this year.)

It’s no surprise, but those who quite literally live on the margins of capital are the most vulnerable to its swings and busts. The price surges in East Palo Alto are more extreme because one-third of the city’s homes went into foreclosure after the subprime crisis, only to be bid and bought back up again during the new tech boom.

There is no reason that the prodigious level of job creation over the last few years here has to negatively impact low-income communities throughout the Bay Area — except for the fact that the peninsula and South Bay suburbs are clinging to a mid-20th century suburban model of development that is no longer suitable for the kind of economy we have in Northern California.

The peninsula and South Bay suburbs are clinging to a mid-20th century suburban model of development that is no longer suitable for the kind of economy we have in Northern California.

The Wall Street Journal had a story on this yesterday: space is so tight that tech companies are paying north of $90 a square foot in Mountain View. Those are Manhattan skyscraper prices for 1980s-era suburban office parks. It is like running the entire industry on the physical equivalent of MS-DOS.

You can either scale the physical infrastructure of the region or you can move the jobs. I favor doing both, but it seems obvious that the world is on an inexorable path towards mass urbanization and that the type of creative and collaborative work done in the industry today favors density.

The younger generation in tech understands that in a knowledge-based economy, the value of what is created in Silicon Valley both economically and culturally is in the network. It depends upon who we can bring and include here — not in physical assets like a piece of land or a home.

But the peninsula cities have majority homeowner voting bases, and their elected political bodies are incentivized to protect these assets through slow-growth policies and exclusionary zoning.

This approach has paid off handsomely. Palo Alto home prices, for instance, have outperformed the S&P 500 by almost 2X over the past 16 years with significantly lower volatility.

And while San Francisco was the second worst metro area in the country for producing housing in the earlier part of this decade, some of the richer peninsula suburbs have done an even crappier job. Menlo Park permitted 22 percent of its state-mandated housing projections from 2007 to 2014, while Palo Alto did 37 percent and Atherton, one of the wealthiest towns in the entire country, did 1 percent. Menlo Park was even sued by three non-profits for not producing enough affordable housing back in 2012

Even more troubling, the scaffolding that all of these cities and the state of California have erected over the last 40 years to make 1960s suburban ranch homes a fantastic store of value also perversely makes them attractive to non-resident overseas capital. This has been more pronounced over the last three years after the Chinese property market plateaued and Xi Jinping embarked on an anti-corruption campaign, which are both driving capital offshore into foreign real estate markets and into a relatively obscure U.S. visa program called EB-5 that was maxed out for the first time in its 24-year history last fall. EB-5 might be OK if it’s an alternate source of financing for big projects that may not otherwise get built like the thousands of proposed homes in San Francisco’s Hunters Point.

But not if overseas capital ends up being parked in empty homes, pricing would-be community members out of homeownership. In San Francisco, it appears relatively limited; a study from the regional think tank SPUR using 2012 data found that only 2.4 percent of housing units were left vacant by non-resident owners for seasonal use.

However, the phenomenon may be larger in the suburbs where property isn’t subject to the same stringent tenant laws. It’s hard to quantify because the region is split between dozens of suburbs, but anecdotally, real estate agents have told the Chronicle that more than one-quarter of current buyers in Palo Alto are from China, fueling concerns about a spate of “ghost homes” inside the tony suburb. We need a new region-wide approach to monitoring this with data.

In aggregate, the costs of this rent-seeking and zoning abuse are enormous to both Silicon Valley and the U.S. economy. Because the infrastructure and housing stock is not expanding with population growth, people are either getting forced out or are going to areas that have fewer job opportunities and weaker social mobility. UC Berkeley economist Enrico Moretti and Chang-Tai Hsieh calculated in a paper last year that if the country’s most economically productive regions like Silicon Valley, New York and Boston had a more elastic housing supply, the aggregate output of the U.S. economy since 1964 would be 13.5 percent larger. That is the equivalent of $2 trillion per year, or $10,000 per American.

Menlo Park thankfully has engaged in some changes, with 202 units being planned for downtown and by allowing a 394-unit complex near Facebook’s headquarters.

But this is not imaginative enough. Facebook has grown its headcount by 48 percent in the last year to just north of 10,000 employees, with roughly half of them in Menlo Park.

A few hundred units is not going to cut it.

Given its market capitalization and position, Facebook is the company in the best position to re-imagine what new urbanism looks like in the old heart of Silicon Valley. In February, they acquired a 56-acre piece of property in Menlo Park for an estimated $400 million and have signaled that they are open to doing more with it than just office space.

So far, they’ve had to go and assure nearby residents in low-income neighborhood of Belle Haven that they are not going to be erecting nine-story buildings on it.

But they should build high and they should offer meaningful concessions — in the tens or hundreds of millions of dollars — for appropriate infrastructure or permanently affordable housing in a quid pro quo deal for dense, tall and walkable workforce housing in a mixed-use, mixed-income environment. If they’re successful, they could demonstrate to the surrounding communities that post-suburbia isn’t so scary after all. That would be the real Facebook effect.

While it isn’t ideal to have a single for-profit corporation influence so much of a city’s development policy like Google in Mountain View or Apple in Cupertino, the current system of governance has produced a short-sighted, fragmented (and frankly selfish) approach that has not kept pace with population growth. This is partly why the tech industry has expanded north into San Francisco, with ripple effects impacting the Latino community in the Mission and the black community in Oakland.

And if the suburban local governments in the south need to extract financial concessions out of these enormous publicly-traded companies to support this density, so be it. In an ideal world, in-fill development should pay for itself through more resident taxpayers. But unfortunately, California’s municipal and public school financing systems are kind of messed up given the property tax caps that home-owning voters gave themselves under 1978’s Proposition 13 and then the requirement of a majority vote for any new revenue-generating fees or taxes under 1996’s Proposition 218.

These deals should also be logistically easier to work out down in the suburbs than in San Francisco, where it’s likely impossible because the tech workforce comprises only roughly 7 percent of the population, is split between 1,800 or so companies and doesn’t have a company with the market capitalization, profitability and dominance of a Google, Apple or Facebook yet.

Anyway, if you are a younger tech worker that favors market-based solutions and is generally dismissive of government for being incompetent or inefficient, remember that public institutions are only as good as the public that holds them accountable. The current system is tilted to favor older commercial and residential property interests, which are extremely organized and which can actually consistently turn people out to vote. Can you?

And remember that you are already paying an extraordinary tax to be here that doesn’t really do anything for infrastructure, transit or education. It is among the highest in the nation.

It is called rent.