Tracking differences between the performance of high- and low-performing students is one way of monitoring equity in education. These differences are referred to as achievement gaps or “score gaps,” and they may widen or narrow over time.

To provide the most up-to-date international data on this topic, NCES recently released Changes Between 2011 and 2019 in Achievement Gaps Between High- and Low-Performing Students in Mathematics and Science: International Results From TIMSS. This interactive web-based Stats in Brief uses data from the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) to explore changes between 2011 and 2019 in the score gaps between students at the 90th percentile (high performing) and the 10th percentile (low performing). The study—which examines data from 47 countries at grade 4, 36 countries at grade 8, and 29 countries at both grades—provides an important picture of prepandemic trends.

This Stats in Brief also provides new analyses of the patterns in score gap changes over the last decade. The focus on patterns sheds light on which part of the achievement distribution may be driving change, which is important for developing appropriate policy responses.

Did score gaps change in the United States and other countries between 2011 and 2019?

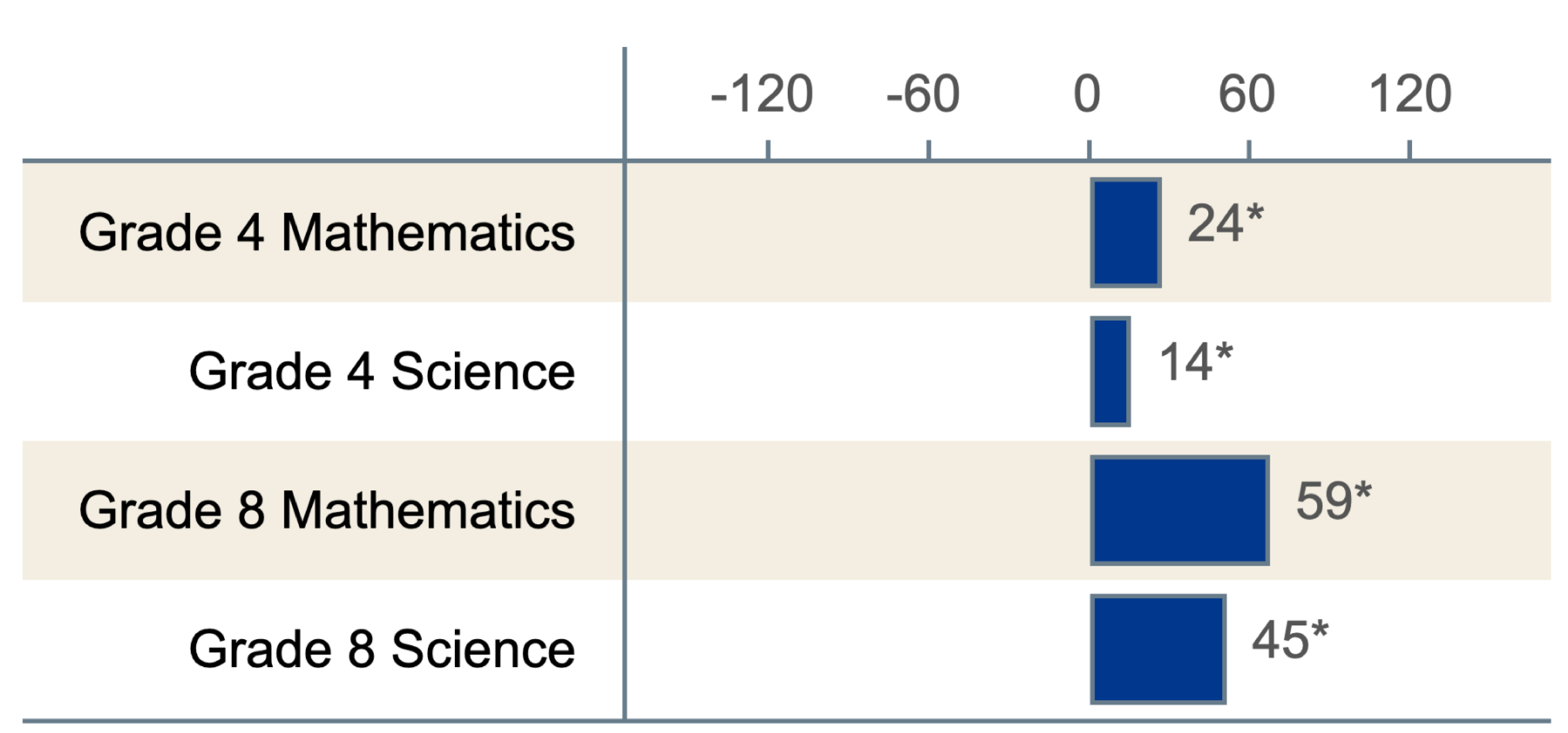

In the United States, score gap changes consistently widened between 2011 and 2019 (figure 1). In fact, the United States was the only country (of 29) where the score gap between high- and low-performing students widened in both mathematics and science at both grade 4 and grade 8.

Figure 1. Changes in scores gaps between high- and low-performing U.S. students between 2011 and 2019

* p < .05. Change in score gap is significant at the .05 level of statistical significance.

SOURCE: Stephens, M., Erberber, E., Tsokodayi, Y., and Fonseca, F. (2022). Changes Between 2011 and 2019 in Achievement Gaps Between High- and Low-Performing Students in Mathematics and Science: International Results From TIMSS (NCES 2022-041). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences. Available at https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2022041.

For any given grade and subject combination, no more than a quarter of participating countries had a score gap that widened, and no more than a third had a score gap that narrowed—further highlighting the uniqueness of the U.S. results.

Did score gaps change because of high-performing students, low-performing students, or both?

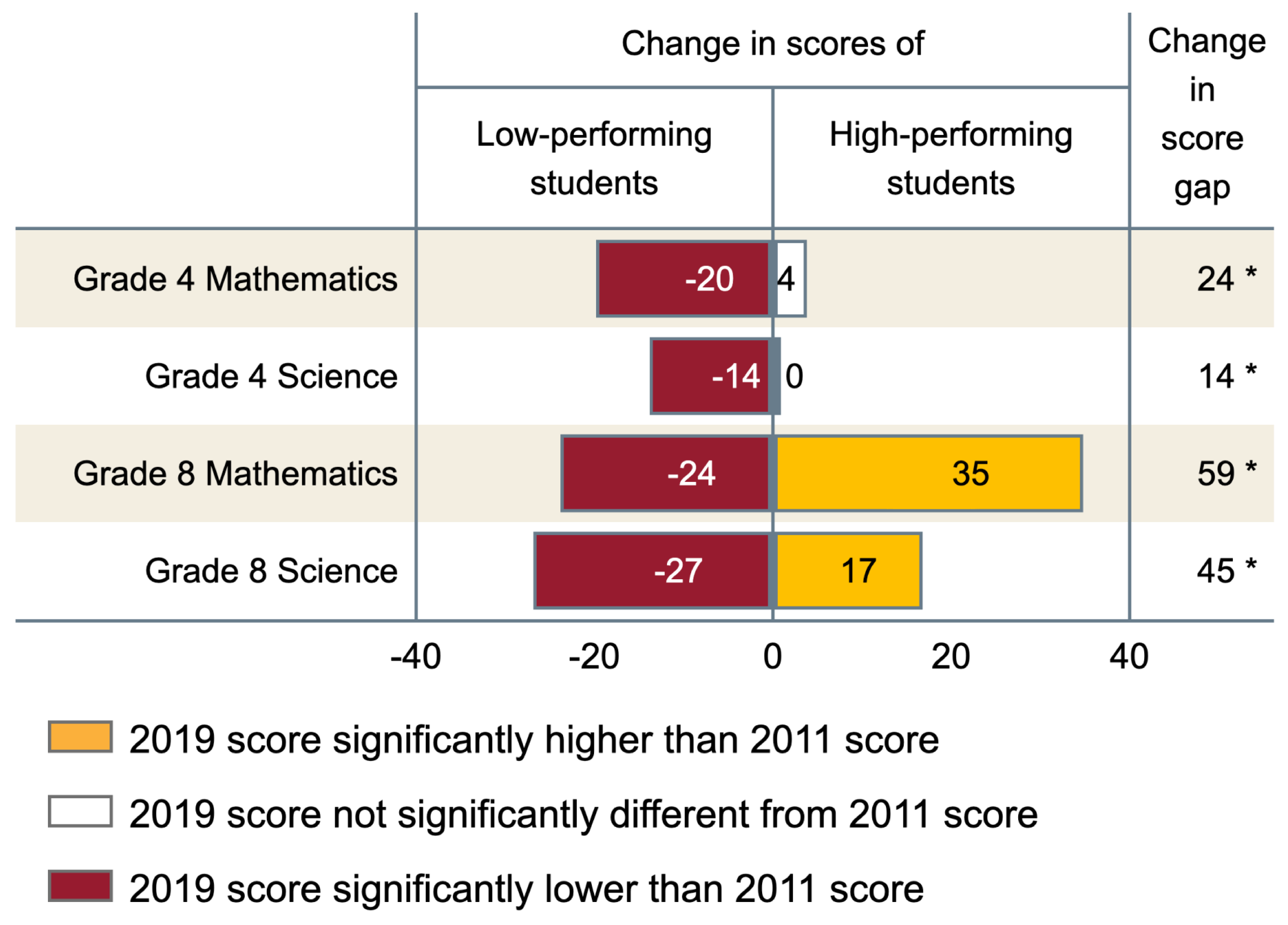

At grade 4, score gaps widened in the United States between 2011 and 2019 due to decreases in low-performing students’ scores, while high-performing students’ scores did not measurably change (figure 2). This was true for both mathematics and science and for most of the countries where score gaps also widened.

Figure 2. Changes in scores of high- and low-performing U.S. students between 2011 and 2019

* p < .05. 2019 score gap is significantly different from 2011 score gap.

SOURCE: Stephens, M., Erberber, E., Tsokodayi, Y., and Fonseca, F. (2022). Changes Between 2011 and 2019 in Achievement Gaps Between High- and Low-Performing Students in Mathematics and Science: International Results From TIMSS (NCES 2022-041). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences. Available at https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2022041.

Low-performing U.S. students’ scores also dropped in both subjects at grade 8, but at this grade, they were accompanied by rises in high-performing students’ scores. This pattern—where the two ends of the distribution move in opposite directions—led to the United States’ relatively large changes in score gaps. Among the other countries with widening score gaps at grade 8, this pattern of divergence was not common in mathematics but was more common in science.

In contrast, in countries where the score gaps narrowed, low-performing students’ scores generally increased. In some cases, the scores of both low- and high-performing students increased, but the scores of low-performing students increased more.

Countries with narrowing score gaps typically also saw their average scores rise between 2011 and 2019, demonstrating improvements in both equity and achievement. This was almost never the case in countries where the scores of low-performing students dropped, highlighting the global importance of not letting this group of students fall behind.

What else can we learn from this TIMSS Stats in Brief?

In addition to providing summary results (described above), this interactive Stats in Brief allows users to select a subject and grade to explore each of the study questions further (exhibit 1). Within each selection, users can choose either a more streamlined or a more expanded view of the cross-country figures and walk through the findings step-by-step while key parts of the figures are highlighted.

Exhibit 1. Preview of the Stats in Brief’s Features

Explore NCES’ new interactive TIMSS Stats in Brief to learn more about how score gaps between high- and low-performing students have changed over time across countries.

Be sure to follow NCES on Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, and YouTube and subscribe to the NCES News Flash to stay up-to-date on TIMSS data releases and resources.

By Maria Stephens and Ebru Erberber, AIR; and Lydia Malley, NCES